Your cart is currently empty!

Category: Books

-

BOOK REVIEW: parasocialite

Brittany Menjivar’s Literary DebutLiterati yet to meet Brittany Menjivar can now do so through her hardcopy publishing debut, a slender prose/poetry collection titled parasocialite. As a cheeky culture correspondent (a Salvadorian born in the DMV) and founder of Car Crash Collective (a late-night lit monthly hosted at Footsie’s Bar in LA’s Cypress Park), Menjivar does not shy from dropping names.

Perhaps she intends no true auto-biographizing, though to counter, Menjivar was subject to a car accident that led to cosmetic surgery, informing her lit collective’s “Car Crash” moniker. In “HOLLYWOOD MOMENTS,” her persona has “made it among people who don’t need to make it.” Being a Yale alum, this could be an adornment of fact. Then in “CATBOY EDIT,” a manipulative prep school narrator works with a classmate to access this student’s brother’s bedroom. Albeit speculative, the narrative linearity suggests a symbolic truth in line with the works of Chris Kraus.

At times, parasocialite achieves broader awareness. In particular, “ANIMAL ABUSE” juxtaposes a girl’s inner quest to attain PETA-level advertorial beauty standards while facing the temptation to watch the 2014 David Haines’ ISIS beheading video. As the collection’s gut-punching climax, Menjivar’s persona turns the experience of witnessing death into a reuniting with a state of rarefied, postnatal innocence. With its many attributions to a higher power, perhaps the work’s thesis is to capture the essence of religious transcendence vis-à-vis colloquial language.

Complementing this dialogue with a creator, “NEVER FORGET” yields a startling syllogism: acceptance of a circumstance may allow one to “exist forever as a symbol” with “a symbol [being] the best shortcut to grace.” Whether connoting wisdom or warning, such formidable truths seem inevitable for a generation born to eternal global cataclysm. And Menjivar seems fit for this task of semantic divination.

Though I wished Menjivar explored more magical realism. Short-lived were the line-by-line joys of “NEVER FORGET.” Here, a 9/11 childbirth in a Lower East Side McDonald’s culminates in miraculous insight. And while “ELEPHANT CROSSING” did veer toward absurdism, it maintained facial symbolism in its satire of American gun violence.

“ELEPHANT CROSSING” highlights Menjivar’s MFA-hewed prosody, with its teen boy putting down an escaped spotted leopard that “whimpered, stumbled back” before “bullets rained down” and the feline “relented” until he “lay in a pool of blood.” “INTERNALIZATION” captures Sylvia Plath’s decorative psychological intricacies when while “heaven could drop in my lap” as “old men” face the “closeness to death” . . . “I sleep with my mouth cracked / To let in the spiders / They weave the most gorgeous / Webs in my throat.”

At its conceptual zenith, “A TRICK FOR SOPHIE” features a young girl compelled to hide her written philosophy from an approaching man, reasoning that Evil “requires such attention” and that for the “broken psyche . . . powerlessness” might serve as an “act of devotion.” Hannah Arendt herself should approve.

Cycling between the mundane and the sublime, Menjivar’s small prayers probe the fantastical to access the reality of a Western woman’s becoming. Tabloid superficiality aside, ample substance awaits discerning eyes.

parasocialite

Brittany Menjivar

Dream Boy Book Club

2024 -

ENVIRONMENT MAKING

Malaya Malandro on CollaborationCreated by Francis Kanai and Malaya Malandro, Everything Is a Self-Portrait is a collection of photographs and poetry produced from years of phone calls and emails between their respective homes in Japan and the US. More than a simple display of two artists’ works, the book is a glimpse into a larger conversation—one that is ongoing. While the book is separated into sections by medium, the visual and written work is fluid. In fact, it’s not even clear there are two artists until you turn to the final page. Kanai and Malandro have formed a shared language, reflecting one another in their work. The result is a beautifully rendered book that allows readers to be voyeurs to their conversations about the world. I had the pleasure of sitting down with Malandro to speak about the book and the process behind it. The following are excerpts from our discussion.

CHRIST: How did you and your collaborator, Francis, meet?

MALANDRO: Through mutual friends on a strange but fated visit to Japan almost seven years ago now. We’ve stayed in touch and fostered this friendship. Our similar, or really complementing, philosophies made fertile soil for a synergetic, creative partnership.

Francis Kanai, Untitled, courtesy of the artist and Malaya Malandro. How did this project begin?

We began talking about working together in late 2019, early 2020—exchanging phone calls and texts about things that interested us. Originally, we just had the desire to work on a project together, but we didn’t have an endpoint in mind. We didn’t know it would be a book. We were just communicating. One of us would say something like, “Oh, I’ve been thinking about 7-Elevens recently,” and then for the next few weeks we’d just be responding to that idea. Through all these conversations I guess we began building these bodies of work, just amassing materials from archival to new work. We were digging through a mass.

When we first met, you were introduced to me as a visual artist. Why this shift to writing, or at least for this project?

I’ve always written poetry, but it was my first time sharing this part of my practice. I think visual or written, there is a sense of time, embodied time—a physical feeling I’m drawn to. With poetry, I feel like I can explore this embodied time and open it up to the creation of environment. Environment making?

I like that phrase, “environment making.” You can see it in the book. You set a scene that is reflected in these photos. I know it wasn’t intentional that you two did that; there was something there, a shared notion. I think the benefit of having those conversations was that it brought a natural affinity for one another, an affinity for one another’s work and what you’re creating.

I think there was an unintentional intention—like where perhaps you don’t hear the music and dance anyway. And when it starts playing somehow the choreography matches up; that our work reflects a similar spirit or ghost that haunts the world, guards the world, has visited both of us and that visit is reflected in the sensibilities in our practice. Maybe! I think we do see each other in our work. In Everything is a Self-Portrait, there is that sense of recognition, that what you see, or maybe better how you see, is your reflection—a portrait you’ve made.

Francis Kanai, Untitled, courtesy of the artist and Malaya Malandro. Everything Is a Self-Portrait

By Francis Kanai and Malaya Malandro

307 Pages

Printed in Takasaki, Japan

Metalabel -

BOOK REVIEW: Two Artists’ Books on Dystopia

The Earth is parched, its water impure. The air is poisonous, awash with industrial effluvia and alive with toxic organisms. Our culture has been radically and relentlessly artificialized, while we are regimented, consumerized, alienated and terrorized. Fortunately, we still have art to heal our wounds, to drive our actions and to provide hope for the future. Today, that work is being done by two books, presenting two bodies of work that are superficially quite different, but deeply and importantly connected.

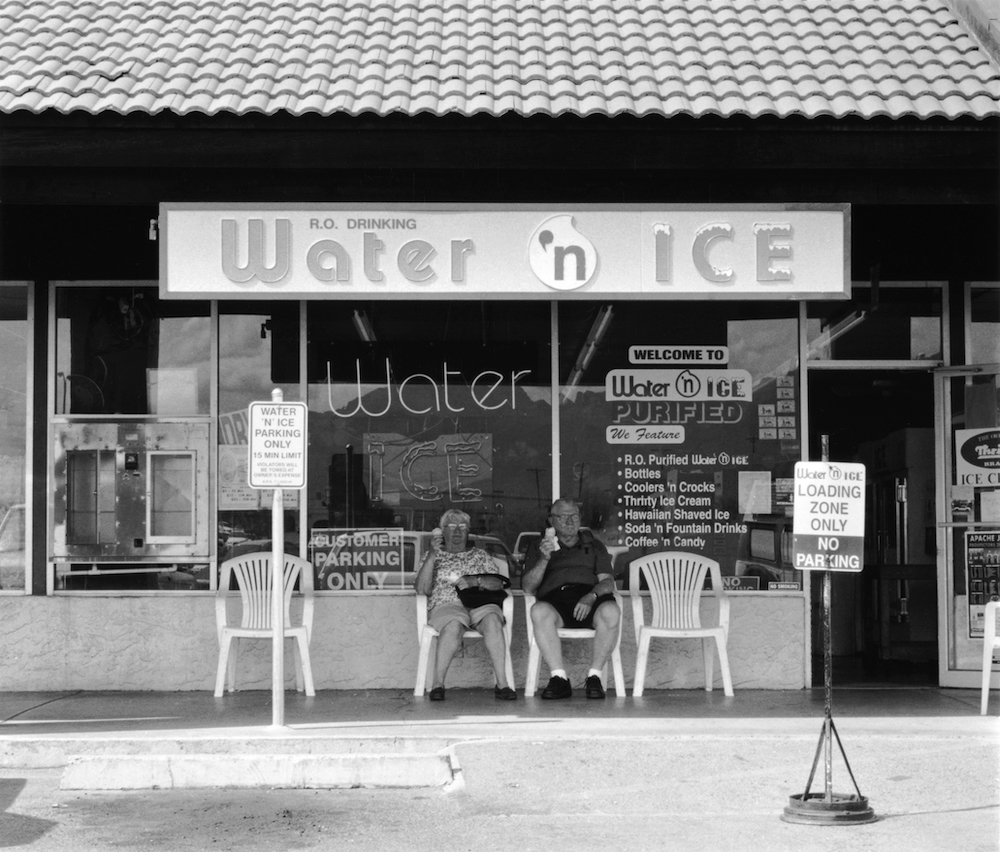

Sant Khalsa’s Crystal Clear || Western Waters makes available the entirety of a project executed during the period from 2000–02, comprising a record of (mostly) strip mall storefronts, unassuming shops dispensing “clear,” not to say “crystal clear,” “pure” and “cool” water, indeed providing a “perfect oasis” of “living water” in the deserts of the southwest: in fact, mostly just tap water purified by reverse osmosis. These are small meticulous prints meant to be seen as a series, each one evoking a particular instance of what at the time was a relatively new phenomenon (now an $11 billion-a-year industry) providing “good” water to folks who are not able to afford pricey branded attempts to market one of life’s most basic necessities.

The photos were gathered throughout southern California and across a number of southwestern states. Their signage often speaks to an immigrant population (Hispanic, Korean, Filipino); and although the artist’s “debts” to Walker Evans and Ed Ruscha (who provided a succinct foreword) are clear in the formalism of the images, the focus on the iconography of water, on its precarious presence in the desert southwest, and on the intricacy of our involvement with its complex ecology as played out in image after image, is entirely the artist’s own—a hallmark of a loving concern evinced throughout an entire career.

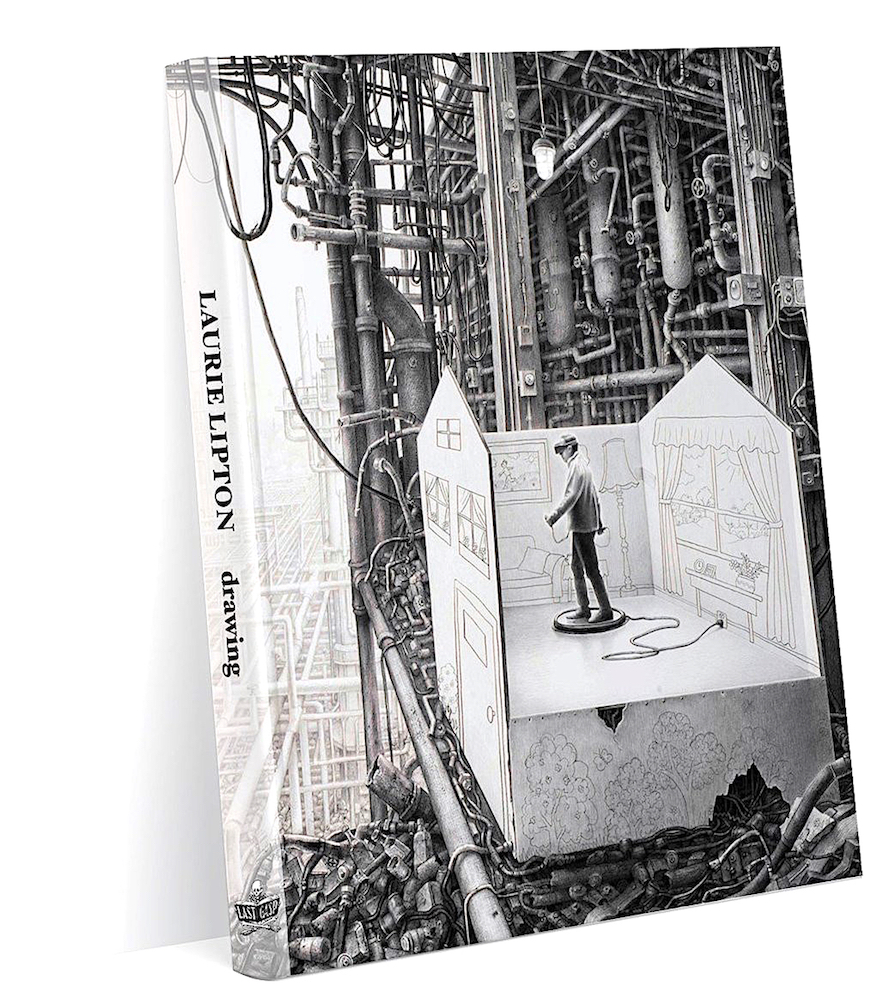

Laurie Lipton, drawing, (San Francisco: Last Gasp, 2022). Laurie Lipton’s new book is titled simply drawing. The work covers the period 2014–22, but its major concern is surely the cultural effects of COVID lockdown. Since Lipton already posits an embattled humankind enmeshed in a culture maximally mechanized, commodified, digitized and virtualized, her evocation of our struggles to retain both an image of authentic self and a sense of genuine community even in her most naturalistically grounded images, can be truly horrifying (compare Alone In My Home, Socializing and You’re On Mute [both 2021]).

Much of the work consists of a series of meticulous fever dreams whose general parameters have long been present in her work, but which seem here to have gained an intensity, aggressiveness and transgressive violence: they defy description in a confined rhetorical space. When not fragmented, constrained and electro-mechanically transmogrified, her actors inhabit a psychic world ranging from selfie narcissism to apocalyptic and agoraphobic paranoia (compare Binge Watching [2018] and Stepping Out [2021]). Yet, in the final instance, it is the endlessly reiterated masses of Lipton’s lock-stepping skeletal bots—smiling consumers all—that have produced the toxic and arid world to which Sant Khalsa’s photographs speak, of “agua pura,” a cool and shady Eden where one can always stock up on “water and ice to go.”

Crystal Clear || Western Waters

By Sant Khalsa

Foreward by Ed Ruscha

72 pages

Minor Mattersdrawing

By Laurie Lipton

112 pages

Last Gasp -

Personal Spirituality

Betye Saar: Black Doll BluesThe dolls we grew up playing with weren’t just dolls—they were alter egos, surrogate friends and family, and sometimes even symbolic forces of the universe. In this beautifully designed book, Betye Saar: Black Doll Blues, we get a chance to look at Saar’s special relationship to dolls: through photographs of her extensive doll collection, sketches and watercolors she has made of her dolls, and the assemblage work she has made over the years that incorporated dolls or parts thereof.

The book begins with an informative intro by Julie Roberts, co-founder and co-director of Roberts Projects, who tells us that when Saar decided to place her archives at the Getty Research Institute, they started sorting through her studio archives and found sketchbooks the artist has kept since the 1960s. The gallery has long represented Saar, so Roberts writes with natural familiarity and depth of knowledge.

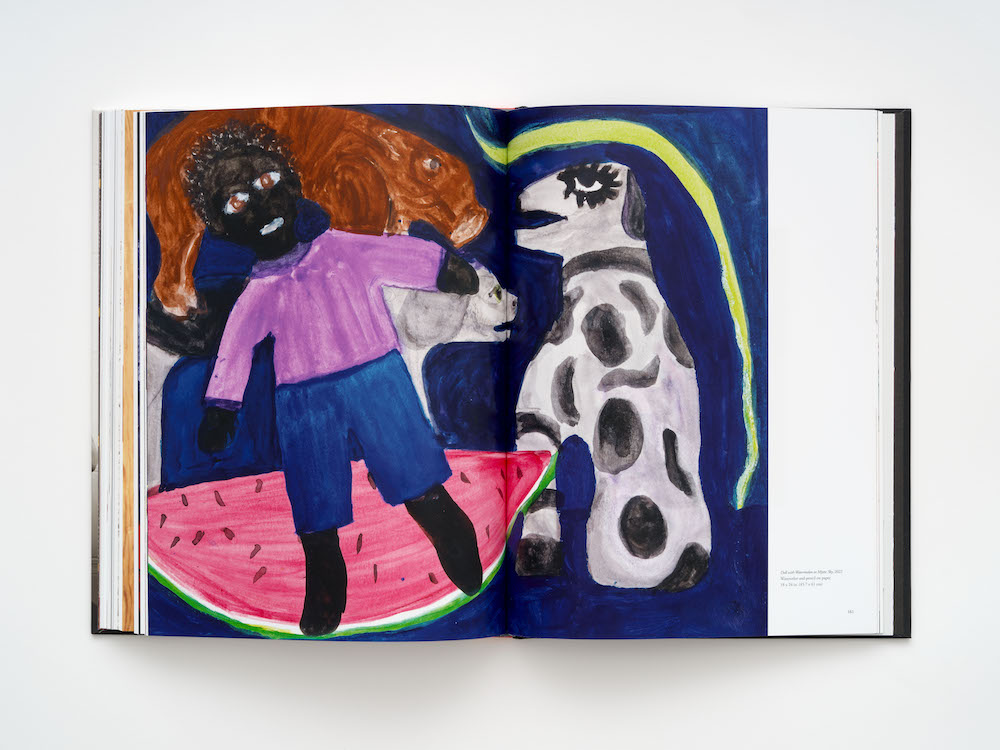

The first chapter is called “Sketchbooks” and shows drawings and watercolors of the Black dolls Saar has been collecting for decades. “While some may view these dolls as derogatory, and I agree some of them are,” Saar says in the book, “I didn’t create these paintings in the same spirit of ‘empowering Aunt Jemima.’ These paintings purely depict the Black dolls as they are, with the purpose of providing love and comfort to their owner.”

Betye Saar: Black Doll Blues, 2022. Published by Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. During COVID Saar filled up several sketchbooks, and some of the artwork is paired with the actual doll she used as model. Yes, she does modify, and she often manages to give the drawn figures a liveliness of expression the physical dolls lack. For example, a late-19th-century cloth doll with a striped red dress becomes a rather energetic Black Floating Doll in Mystic Sky in 2022. Saar’s watercolor has the figure at a diagonal on the paper, her lips wearing a smile and her body floating against a dark blue sky filled with yellow stars, crescent moons and a ringed planet. She has escaped Earth, she is in the cosmos! That background touches on Saar’s longtime fascination for the mystical—the notebooks also include sketches of a hand with an eye in the palm, the sun radiating energy and light to the earth and moon, and a rainbow that arcs across two pages of a spiral notebook.

There’s even the story about how she found the Aunt Jemima doll that became her famous assemblage piece, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). Saar bought her at a swap meet: “She is a plastic kitchen accessory that had a notepad on the front of her skirt,” she says. “The broom handle is a pencil and on her left side I mirrored it with a plastic toy rifle.”

Some art books seem rather patched together, their material and chapters grouped randomly, but this one holds together from beginning to end, both in text and in pictures. Having seen some of these sketchbooks at Saar’s recent LACMA exhibition, I found the reproductions to be excellent, with strong colors and sharp details. Of course, much of this unity is due to Saar’s vision, which has been remarkably consistent since she started making art in the 1960s. Now in her 90s, she has produced a body of work that has forced us to re-examine the depiction of the Black figure in visual culture, and also to recognize personal spirituality rooted in folk traditions.

-

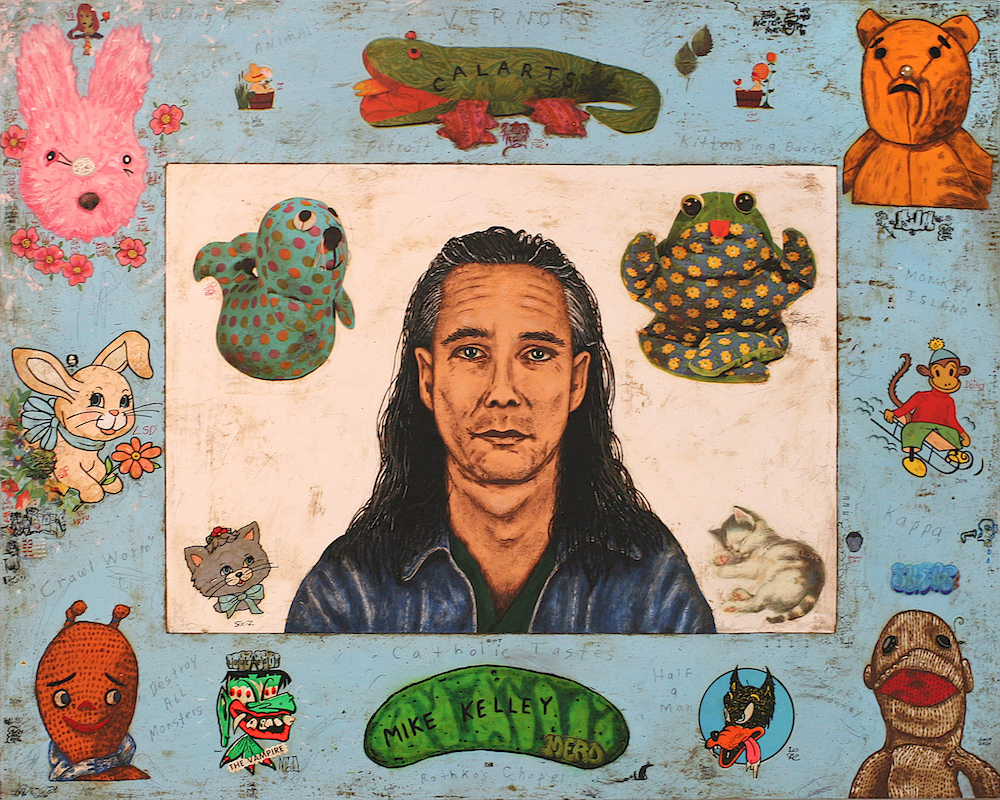

A Few of Jeffrey Vallance’s Favorite Things

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”] [et_pb_row admin_label=”row”] [et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]Jeffrey Vallance holds a unique position in the LA art world. A contemporary of Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Jim Shaw, et al, his work has had a comparable impact locally and internationally, while not transitioning to the industrial fabrication mode demanded by the global fiscal laundromat subdivision AKA The Art World. Part of the reason is that he’s actually from LA—the Valley, specifically—which somehow means you can’t actually represent LA to the rest of TAW.

Mostly though, it’s because Vallance responded to his initial burst of fame by embarking on an extended peripatetic global R&D expedition that had nothing to do with Kunsthallen, art fairs, or high-end public art commissions, but rather Kings of Tonga, Presidents of Iceland, and Las Vegas vanity museums. He never so much fell off The Art World’s radar as evaded capture like some international man of mystery.

Yet another factor is that Vallance writes about his own projects better than any hack critic could, with a deadpan humor and open-mindedness completely analogous to his idiosyncratic semiotic investigations. In 1995, in conjunction with a survey show at SMMOA, Art Issues Press published The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978–1994—encompassing the Tonga and Iceland adventures, as well as his first forays into paranormal reportage and, of course, the last (and subsequent) rites of Blinky the Friendly Hen—the Ralph’s fryer whose pet cemetery funeral service landed Vallance on Letterman and MTV.

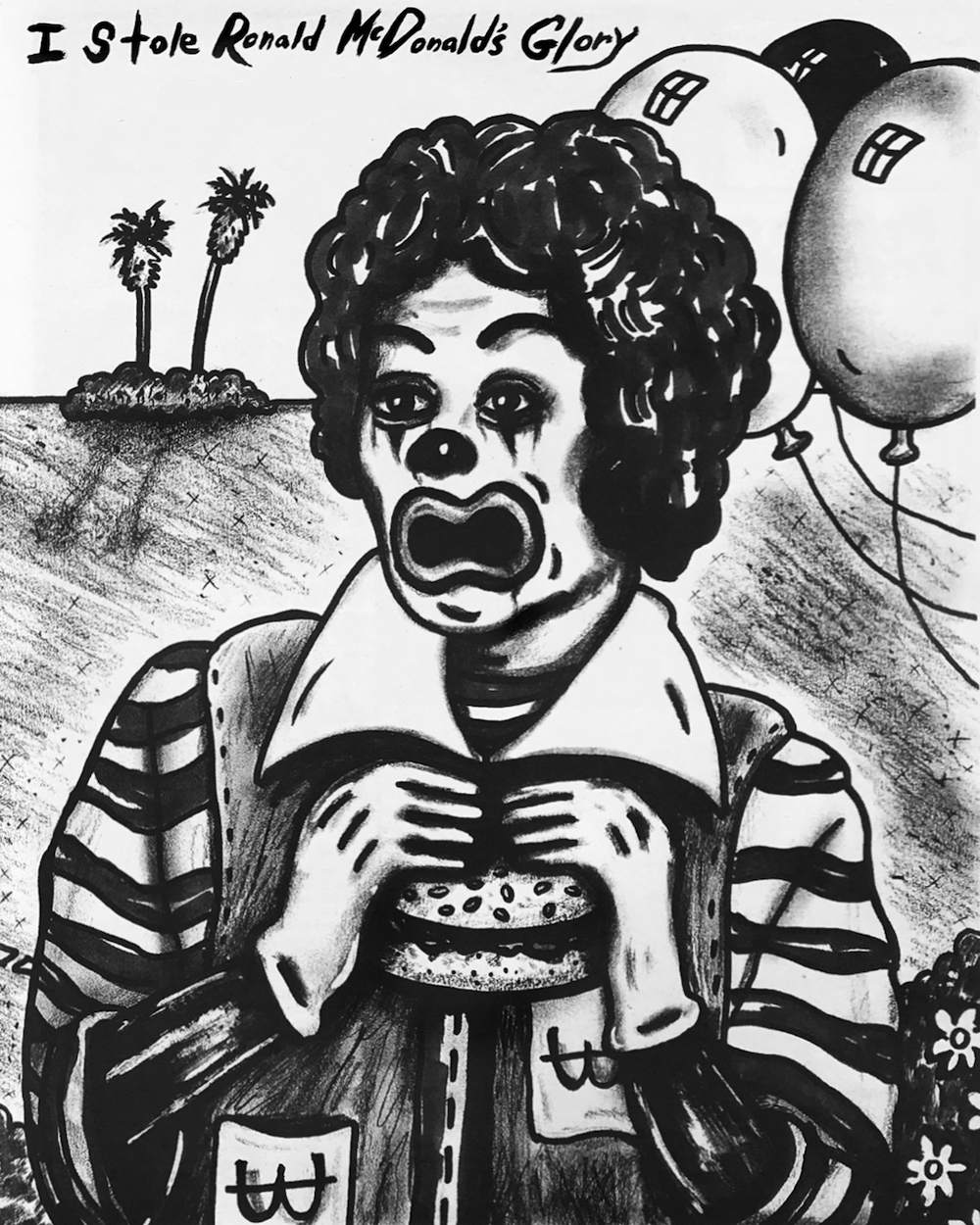

Jeffrey Vallance, The Clowns of Turin: Found on the Holy Shroud, 1996. Collage, pencil and marker on paper, 22 x 29 ¾ in. Collection of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA. Long overdue, A Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings collects close to 700 pages of Vallance’s musings and reports from the intervening decades. That may sound daunting, but this ain’t War & Peace—nor Being and Nothingness neither. Not that it isn’t narratively compelling or philosophically deep—but it’s funny.

And entertaining in many other ways—strangely informative like the best internet curations, or like your weird uncle who gave you Charles Fort’s The Book of the Damned and a sealed vinyl copy of Spiro T. Agnew Speaks Out for your 12th Kwanzaa. A hundred little stories forming a cubist mosaic of a singular artist’s singular journey.

Art historically, the ginormous yellow tome is a gold mine, providing off-the-cuff anecdotal accounts of Vallance’s legendary curatorial interventions in various offbeat thematic museums in Vegas, while elsewhere detailing extensive cross-cultural

research into the religious, anthropological and philosophical significance of clowns.As promised by the subtitle, much of the work addresses spirituality, religion, shamanism and paranormal phenomenology. Richard Nixon, Thomas Kinkade, Martin Luther, Charlie Manson, Ronald McDonald, the Loch Ness Monster and other spiritual teachers all make appearances. It’s not a fluke that Vallance’s curiosity-driven ideational flow is so reminiscent of an extended Wikipedia surf.

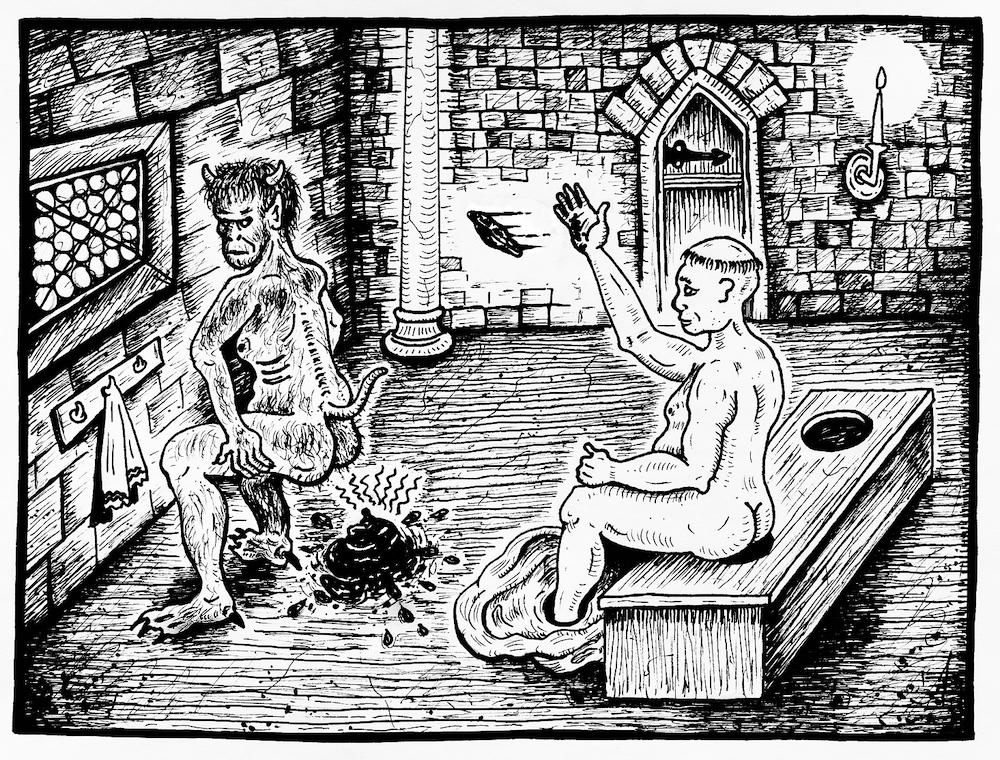

Jeffrey Vallance, Luther on the Privy, Seeing an Apparition of the Devil, 2000. Courtesy of Jeffrey Vallance and Tanya Bonakdar. Much of Vallance’s most significant recent works have been embodied—however ephemerally—in his absurd and prolific social media activity, with Facebook groups that range from the absolutely authentic Valley Plein Air Club to the mind-scrambling Polytheistic Butt Plugs.

Consequently, Vallance’s Voyage to Extremes seems to me to be the most successful literary embodiment of the human cognitive structures that have evolved with the internet—not from imitation, but from pre-existing structural resonance. A playful, weightless curiosity may seem like a fey and inconsequential thing, but when it drifts across a border as if the border wasn’t there, watch out! That’s when Luther’s excrement hits the Devil’s fan! And that’s why the internet is still (though sadly less and less) dangerous.

In counterpoint to this ADHD-currency, Vallance has provided a newly written overarching autobiographical framework. Arranged approximately chronologically, the included materials chart Vallance’s aforementioned trips, his mythic residencies in Vegas and Umea (Sweden), and his return to the San Fernando Valley (from whence he deploys his current, peculiar global/local influence).

This interstitial narrative skeleton generates a knowing—occasionally dark, even justifiably bitter—storyline detailing the obstacles and joys of being an artist in the 21st century, from which the oddball essays radiate like feathers on a bipolar peacock. The power of art to short circuit the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune have never been articulated more elegantly.

From excrement to ecstasy, from Texas to the Arctic Circle, from the taxonomy of butt plugs to the etymology of the Tetragrammaton—all the indeterminate territories TAW tiptoes around—Jeffrey Vallance relentlessly but non-aggressively burrows beneath, collapsing rickety categorical imperatives in favor of rhizomatic ‘patacritical revelations that are equal parts Art Bell, Roland Barthes, and S.J. Perelman. Copiously illustrated.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column] [/et_pb_row] [/et_pb_section] -

Book Review: A Measured Coolness

Building + Becoming by Amir ZakiBuilding + Becoming

By Amir Zaki

272 pages

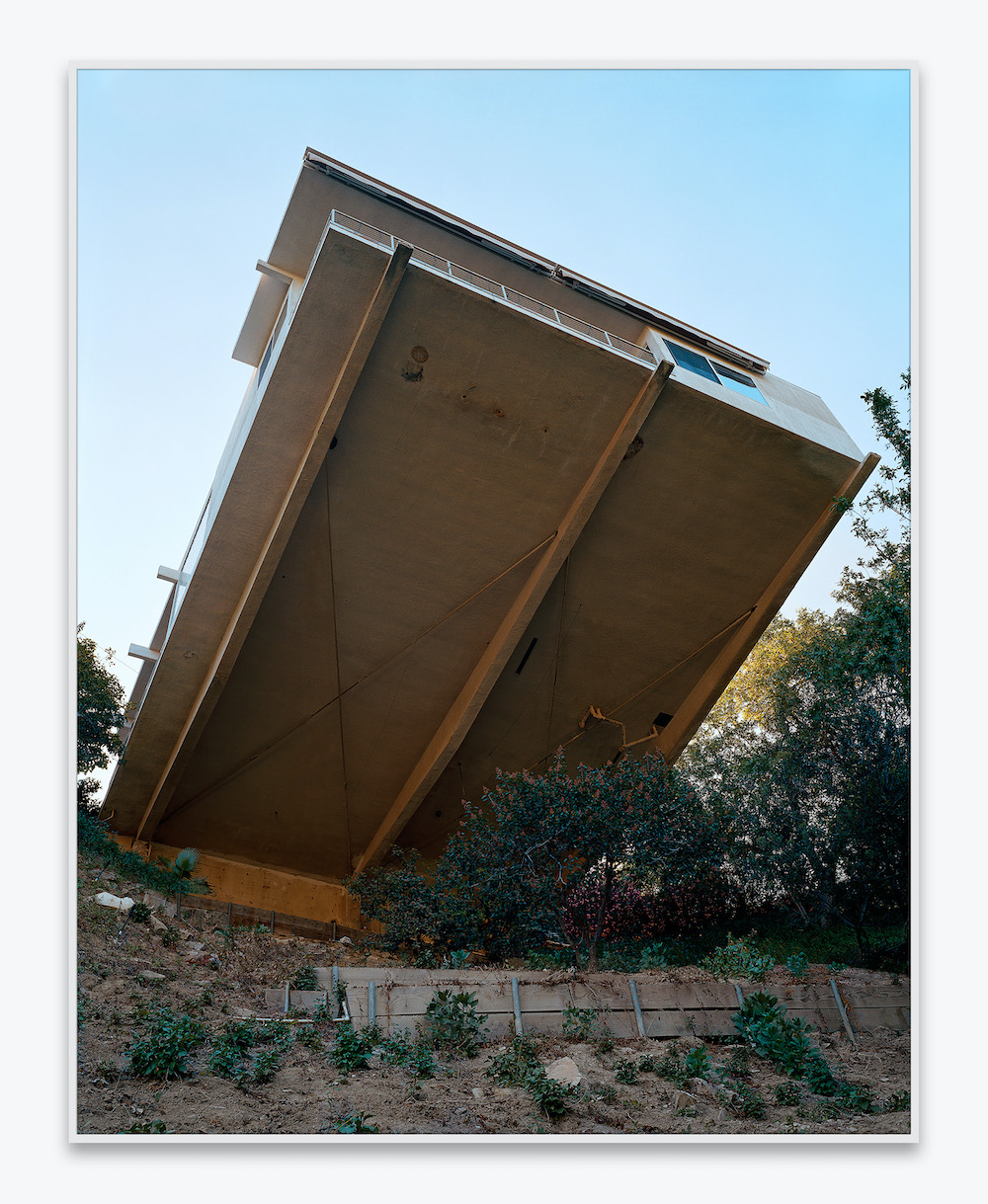

X Artists’ Books and DoppelHouse PressThe works of Amir Zaki subtly subverts analog photography’s long-held truth claims. His photography, surveyed in the newly published artist book Building + Becoming, addresses the artist’s digital manipulation and, setting aside the medium’s presumed objectivity and fidelity to representation, invites the question, “to what end”?

Illuminated by two texts, “Stealing Light,” a conversation with Corrina Peipon, and “Addition by Subtraction,” an essay by Jennifer Ashton and Walter Benn Michaels, Building + Becoming explores Zaki’s formation as an artist, touches briefly on biographical notes and artistic lineage and examines his process while engaging in critical dialog. Ashton and Michaels also analyze the technological and post-production practices integral to Zaki’s images. At the core of their inquiry is the apparent contradiction in his claim of the Modernist tradition, via Edward Weston, and his use of a Gigapan device, which enables him to take a series of adjacent photos and stitch them together with software, resulting in works that defy the singular perspective associated with Modernist photography.

Computational imaging—to paraphrase a definition given by researcher and computational photography pioneer Marc Levoy, the use of computational methods to produce photographs that could not have been taken by a traditional camera—presents an alternate framework for considering Zaki’s technology-assisted creation of large-scale, information-saturated photographs.

The monograph is full of meticulously printed photographs that are just as beguiling and seductive as I know them to be in person, though on a reduced scale. One of the notions I have harbored—a notion the artist sidestepped when I interviewed him in 2019 about his “Empty Vessel” series (photos of California skateparks and broken ceramic vessels)—is that his work offers images of iconic California settings, which are complicated by the subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, alterations introduced through post-production editing.

In his conversation with Peipon, Zaki rejects what he calls the cynicism, hollowness and political and moralistic overtones of postmodernism. Though this description lacks definition, there is a point there about work that delivers straightforward political punchlines rather than examining the complexities and apparent contradictions of something, or engaging in open-ended inquiry. But inherent in any conversation on whether politics should influence art, or vice versa, is the question of what art can do, or what one wants their work to do.

In responding to Zaki’s work, I find myself oscillating between the sensuousness of his photographs and my own desire for art to be revolutionary—that is, for art to engage in conversations that challenge and alter individuals, society and politics, for art to be at the core of vigorous debate. I see in Zaki’s work—in several of his series—a measured coolness, which combined with his explicit editing, complicates the images beyond mere manifestations of desire, as Zaki claims for them in conversation with Peipon. Think of the imposing bellies of houses (Untitled (OH_19X), 2004) perched on hillsides without support columns in his “Spring Through Winter” series, or the crumbling or close to it beachside cliffs with what appear to be private beach-access staircases (Coastline Cliffside 16, 2012, or Coastline Cliffside 22, 2012) in “Time Moves Still.” These photographs produce a kind of estrangement from the familiar and propose a darker, grittier reality that lies beyond the idyllic vision. Even while evoking Weston’s neoclassicism (“Time Moves Still,” “Formal Matter” and other series), Zaki’s photographs form a kind of speculative work. Further, they suggest a deconstruction of the attainability of success, as a state that is either just out of reach or threatening to come crashing down. As theorist and critic Fredric Jameson notes in Archaeologies of the Future, speculative vernacular creates space for a nuanced critique of social conventions, structures and politics.

Ashton and Michaels discuss Zaki’s use of technology at length. Other artists creating photographic works with technology and information systems have done so more directly to activate critique or commentary. For example, Jenny O’Dell’s “Satellite Collections” and “Satellite Landscapes” shift the point of view to planetary systems. Doug Rickard’s “A New American Picture” series, taken from Google Street View, relies on the ubiquity of Google to comment on racial inequity and privacy issues.

Arguably, all three, diverse as they are, find common lineage in Bernd and Hilla Becher’s work and in photography’s use as a conceptual strategy, as seen in Ed Ruscha’s Some Los Angeles Apartments and other series. That extends to the New Topographics artists, whom Zaki counts in his lineage (specifically the Bechers, Joe Deal and Lewis Baltz), and who also moved photography beyond the singular image and mythologizing of Weston’s neoclassicism, into the realm of documentary, taxonomies and social critique. But the contemporary moment is full of images and objects that occupy both sensuous and revolutionary spaces, simultaneously

-

Book Review: Heartfelt Moments

Portrait of an Artist by Hugo Huerta MarinPortrait of an Artist

By Hugo Huerta Marin

424 pages

PrestelWhat exactly is a portrait? In art, “portrait” is generally understood to mean a visual likeness or representation. One could argue that a photographic portrait captures this visual likeness more closely than would a painting or drawing. It is also possible to create a literary portrait. Embracing this multiplicity of the word, author and photographer Hugo Huerta Marin presents Portrait of an Artist, a gripping book of candid Polaroids and captivating interviews with 25 creative women, including visual arts titans like Tracey Emin and Kiki Smith, and legendary actresses like Cate Blanchett and Uma Thurman.

Created over a seven-year period beginning with Marina Abromavic, whose studio Huerta Marin joined in 2014 as art director, Portrait of an Artist captures heartfelt moments of self-reflection, as well as deeper, thought-provoking conversations on political and social issues. With fascinating anecdotes and insightful commentary, the interviews make the book difficult to put down. Reading the artists’ words and seeing their stories evolve is a joy.

A highlight of the book is the interview with Carrie Mae Weems, which includes her personal account of making her most famous body of work, The Kitchen Table (1990). In this black-and-white photographic series, Weems acts as her own subject, donning different outfits as people cycle through the images, all taken from the end of a long, wooden table in the artist’s kitchen. A single light hangs overhead, illuminating the sitters below as they engage in moments of intimacy, sadness, frustration and introspection.

Yoko Ono, New York, 2016. Weems tells Huerta Marin how the photographs were created at a time when she was teaching college students. Frequent conversations about the male gaze in art made her question how young women were thinking about themselves. At the same time, Weems noted how Black bodies and Black women specifically were absent from art theory in general. “I thought about the ways the gaze could be focused, could be challenged, could be re-contextualized to bring in Black bodies…it was a wonderful endeavor. It was as though all the lightbulbs were turned on and I had a sense of clarity,” she said (p.108).

In some shining moments of the book, Huerta Marin gives a snapshot of various periods of the art, film, fashion and music industries in general. The late Agnès Varda describes writing and directing her first film, La Pointe Courte (1955), at the age of 25 and how excited the locals were to be featured in the film without pay, “It was possible to do that back in the fifties,” Varda said (p.405). Yoko Ono reminisces about her iconic “loft concerts” of the 1960s in which she invited artists and musicians to freely express themselves in her New York City apartment that she rented for $50.50 a month. Diane Von Fürstenberg describes sexual freedom, her friendship with Andy Warhol and the party-filled art hub of New York in the 1970s. Tracey Emin remembers life in London in the 1990s, as a member of the Young British Artists, staying out until 5 am and getting up at 10 am the next day: “I can’t believe we got any work done” (p.157).

Agnès Varda, Paris, 2018. From a technical standpoint, the book gives valuable insight into the art of conducting an interview. Huerta Marin asks specific queries tailored to the sitter’s practice, as well as a handful of similar questions for several of the artists. Questions such as “What are your thoughts on the rise of the artist as celebrity?” and “What are your thoughts on the big international art fairs?” reveal the broad extent to which the artists’ opinions vary. Responding to the latter, Weems calls the market surrounding fairs obscene, while Shirin Neshat expresses the value of such a stage for an artist’s career. Emin echoes both sentiments, describing her experience representing Great Britain in the Venice Biennale as “amazing on the one hand, but somehow soul-destroying on the other” (p.162).

Some of the most beautiful parts of the book come from questions that are wholly unrelated to art. Huerta Marin often asks, “Do you have any recurring dreams?” While many answers reveal high levels of stress and anxiety, Yoko Ono’s answer is as poetic as expected: “That this world will become a peaceful place” (p.148). Such moments are poignant reminders of the artists’ humanity.

Portrait of an Artist is intimate, personal and inspiring. The sitters’ comfort is clear and comes through in their heartfelt honesty. Huerta Marin skillfully manages to make deep connections with each of the 25 trailblazing women, pushing the boundaries of what it means to create a portrait.

-

Book Review: Dystopia Redux

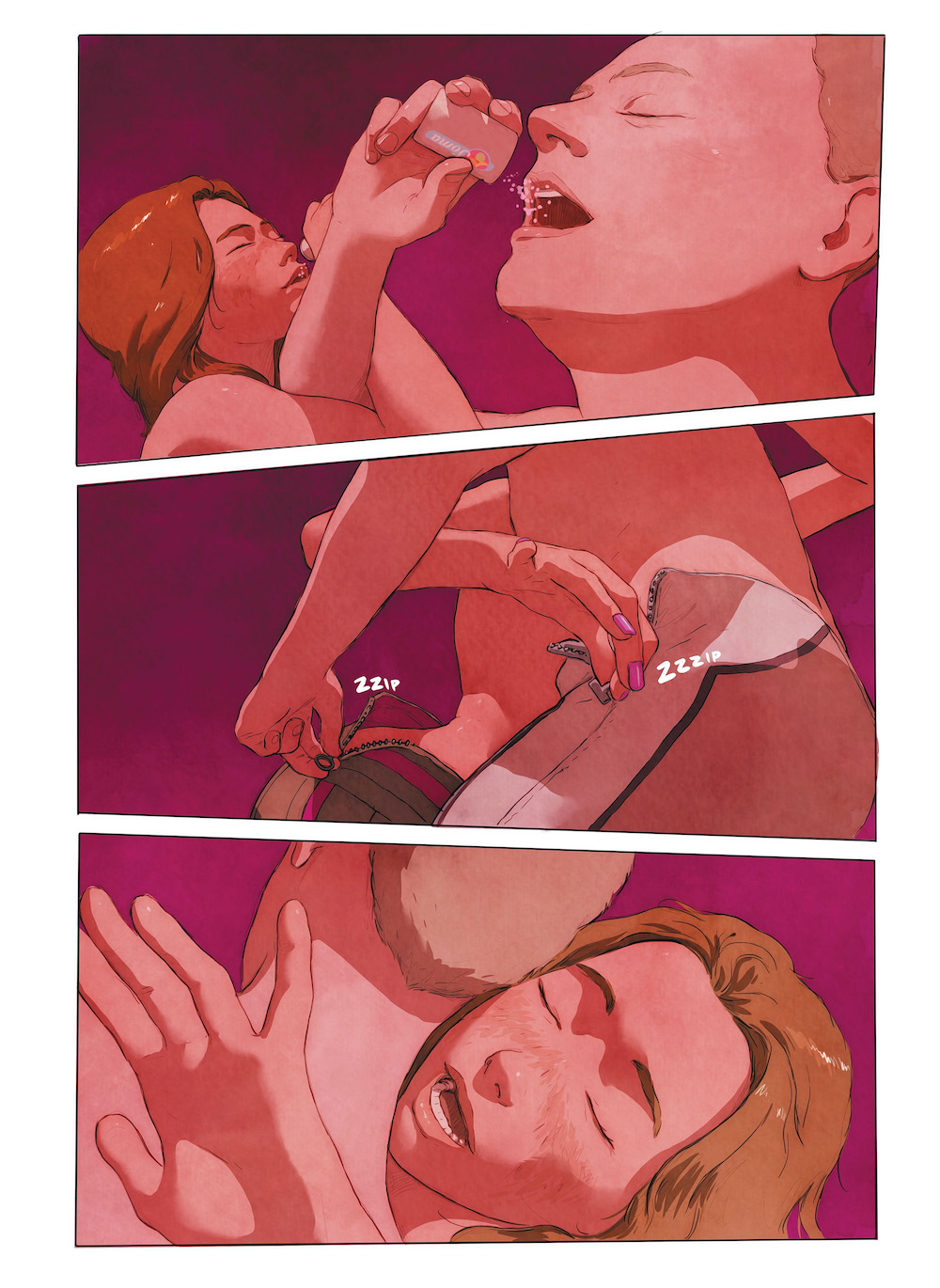

Brave New World: A Graphic Novel by Fred FordhamBrave New World: A Graphic Novel

Adapted and Illustrated by Fred Fordham

234 pages

Harper Collins

Original Text © 1932, 1946 by Aldous HuxleyOh wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! Oh brave new world that has such people in’t!

—William Shakespeare, The TempestAlmost a century after its initial publication in 1932, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World has been solidified as a classic of dystopian science fiction (often bookended with its inverted mirror image, George Orwell’s 1984). In addition, it has now been wonderfully adapted and reframed as a graphic novel by Fred Fordham.

Among the most striking aspects of Huxley’s book are the author’s prescient, relentlessly chilling treatments of genetic engineering and psychological conditioning, and his brilliant evocation of a society built on the twin poles of “stability” and “promiscuity.” Both Fordham’s script (to a great extent a carefully edited version of the original text) and his restrained yet forceful visual style work to communicate these complexities. His judicious use of an extremely tight visual focus, a relentless intercutting between various narrative arcs of the unfolding plot, and the use of tonal overlays to force particular emotional responses in the viewer, also drive the complicated story.

Meanwhile, uninhibited indulgence in sex and SOMA mask the cultural losses that are the inevitable price of a stable existence. Love, family, religion, science, literature, risk and independent thought: all these are now gone, replaced by relentless consumption and pointless recreation: electro-magnetic golf and centrifugal bumble-puppy, extravagantly indulgent sensuality at plot-free feelie theatricals, and the empty spasmodic release of a drug-induced Orgy-Porgy or the faux spirituality of the weekly Community Sing.

Yet a few individuals among those blessed with the genetics and conditioning of the highest castes are able to intuit something of the machinery behind the façade. Hence the inevitable tragedies that unravel the lives of the alienated alpha, Bernard Marx, and the wide-eyed beta, Lenina Crowne. Likewise Bernard’s brilliant friend the erstwhile poet Helmholtz Watson; the twice-outcast John Savage and his scarred and forgotten mother; the socially-committed Hatcheries Director and the self-denying World Controller. No longer infinitely fungible cells within the social order, they have become the necessary sacrifices demanded by the system for its own perpetuation.

When the novel first appeared in 1932, Huxley’s utopia-gone-awry seemed to many left-wing reviewers to be archly elitist and inadequately anti-fascist, since it posited the inevitable triumph of mindless consumer capitalism, with class struggle replaced by a rigid neo-medieval caste system. Today, however, the situation is quite different. Globalized post-industrial capital seems poised to deliver exactly the kind of consumption that Huxley predicted. Meanwhile, endless iterations of self-realization therapy and the arrival of “micro-aggression” and psychedelic “micro-dosing” suggest that life devoid of every emotional hassle is indeed a real possibility.

In short, Brave New World remains troublesome today, perhaps even more pressing in its messaging and complex in its resonance than it was 90 years ago. It’s also a heck of a fun summer read. Very highly recommended

-

Book Review: Criminal Culture

Portrait of a Thief by Grace D. LiPortrait of a Thief

By Grace D. Li

369 pages

Tiny Reparations BooksThe thorny issues of restitution and museums’ complicity in retaining looted artwork do not tend to make for light summer reading. But a breezy new novel turns these issues into the basis of a high-stakes heist. Grace D. Li’s, Portrait of a Thief, manages to be both portrait and landscape—a portrait of college students on the cusp of adulthood set in the landscape of contemporary museums.

First, you’ll have to accept the wild premise that a billionaire is offering a group of college students $50 million to steal (or return) five bronze sculptures, looted from the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, from museums around Europe and the US. Despite their inexperience, they fill the requisite heist tropes: a hacker, a driver, an art historian/leader, a con person and a thief. All are also enrolled at elite US universities; “international art thieves with midterms next week,” as one character says. After a few Zoom calls and international flights, they’re on their way.

More than a little suspension of disbelief is demanded for the timelines and technicalities, such as why would one use Zoom or Google Docs to plan a top-secret theft. But more interesting than the mechanics are the book’s challenges to the museums’ perceived objectivity and the ongoing legacy of colonial perspectives that shape our ideas of history, including what objects get displayed, where and how. While the concepts occasionally get oversimplified through demands of the plot, having a novel raise those questions and perspectives is no bad thing. This timely novel arrives at a point of sea change, as institutions are starting to shift their own points of view: Earlier this year, the Smithsonian announced its decision to repatriate the looted Benin bronzes in its collection, and the UK agreed to talks about the long-contested Parthenon marbles in the British Museum.

The novel’s chief strength is its sensitivity in dealing with the Chinese-American experience—especially when the past few years have seen a horrific rise in hate crimes targeting Asian-Americans in the US. Li deftly integrates the characters’ experiences with the books’ action, weaving in the varied feelings of in-betweeness and longings for belonging and achievement that motivate the characters.

The portraits feel true-to-life, but the setting seems more like a romantic, light-suffused landscape. The sinuous descriptions often dwell on visual themes without driving progress—fall, for example, is described in Los Angeles, New York, Massachusetts, North Carolina and Texas. Though this meandering slows the reader, it also underscores the characters’ youthful idealism, especially as it relates to their college experiences. (Interestingly, while thoroughly challenging museums, the book doesn’t do much to interrogate the problems of elite universities beyond the pressure to attend them.) Though uneven in some of its execution, the story’s visual qualities lend themselves to adaptation: A Netflix production is already in the works, and will no doubt carry the book’s caper across cities and campuses into a glossy production.

Towards the end of the book, one character considers

whether taking a job at a leading museum could allow them to (slowly, eventually) effect institutional change. Portrait of a Thief seems to answer this question both on the page and the shelf with the argument that change is more swiftly achieved by external pressure —books and voices like these advocating for anti-colonial perspectives to counteract centuries of control -

Book Review: Burden of Dreams

Poetic Practical: The Unrealized Work of Chris BurdenPoetic Practical: The Unrealized Work of Chris Burden

Contributors: Donatien Grau, Yayoi Shionoiri, Sydney Stutterheim, Andie Trainer

284 pages

GagosianIt’s impossible to think of the Los Angeles art scene without considering Chris Burden, an incisive social commentator who approached artmaking with both childlike wonder and fearless abandon. His now-legendary performance-art pieces from the early 1970s and subsequent 40-year practice in sculpture, installation, video and mixed-media projects have become canonized as some of the most daring, and outright phantastic, innovations in the history of art.

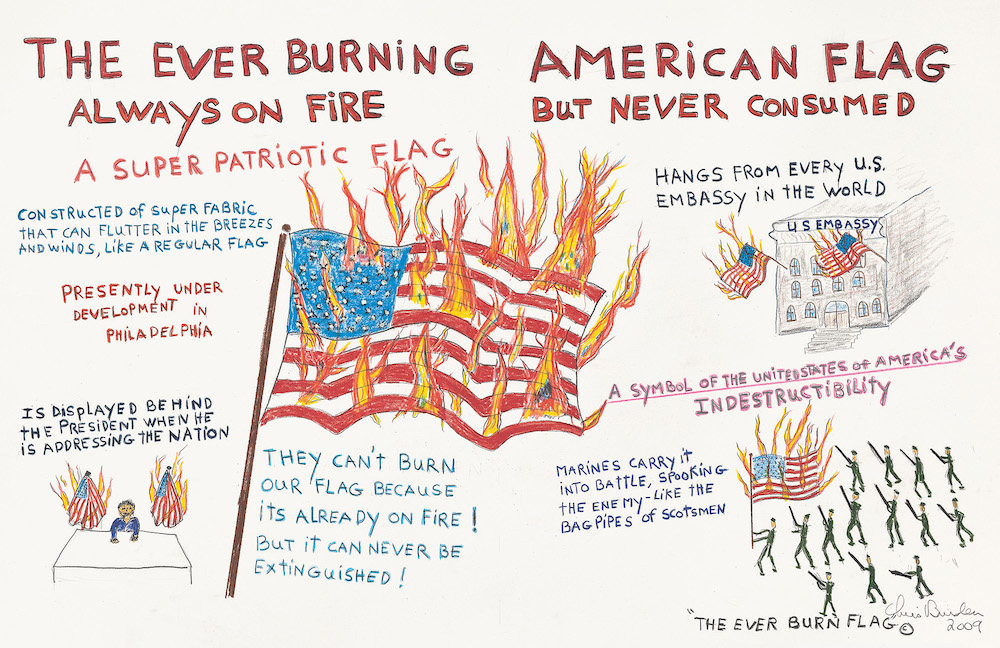

A lavish new book from Gagosian—Poetic Practical: The Unrealized Work of Chris Burden—celebrates Burden’s breadth as it’s never been seen before, with detailed examinations of 67 unrealized projects that existed in various stages of development at the time of his death in 2015. The extensively researched and illustrated book incorporates archival materials from the notebooks Burden painstakingly kept, as well as newly commissioned photographs of the artist’s studio, property and ongoing projects.

Model for the installation “Xanadu” as proposed to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2008 © 2022 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy of Joel Searles and Gagosian. Because Poetic Practical is based on unfinished gestures and ideas rather than actualized objects, its contributors had to resort to a speculative, forensic approach in its assembly. Some of these unrealized works began as mere stand-alone sketches; others included detailed plans that Burden routinely revisited; and others are evolutions of realized projects that Burden considered not to have reached their final forms.

The book makes it abundantly clear that Burden’s ideas never stopped flowing and that the scope of his vision never stopped growing. One of the most memorable propositions from the book is the drawing for The Ever Burning American Flag, an idea Burden had in 2009 for “a super patriotic flag,” forever ablaze but never consumed, that would hang from every embassy in the world and be marched into battle—a piercingly tongue-in-cheek symbol of American indestructibility and the urge for dominance.

Drawing for “The Ever Burning American Flag,” 2009, © 2022 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy of the Chris Burden Estate and Gagosian. An underlying theme in Burden’s work was examining the systems of power that allows society to function, particularly ones that test the limits of art institutions in how far they will bend to an artist’s will, and what they will sacrifice in the name of art. In what Poetic Practical describes as Burden’s “incomplete magnum opus,” the artist proposed to different institutions several iterations of “Xanadu,” a dreamlike model city built to scale and inhabited by Burden’s monumental urban sculptures. The book bears witness to the fact that Burden was always earnest in his investigations, no matter how improbable his ideas, and took his role as an artist as someone uniquely qualified to speak truth to power very seriously.

The true magic of the book lies in the fact that Burden’s realized and unrealized works alike were all rooted in interrogating the potentiality of outlandish concepts. There’s something undeniably beautiful about the untouchable purity of vision embodied by these unrealized projects—they are unadulterated by physical, financial or practical limitations, free to be envisaged at their fullest potential. In this way, a book like Poetic Practical, dedicated to the presumed boundaries of impossibility and based in abstract pipedreams, is a truly unparalleled feat—and the most uniquely fitting tribute to Burden’s legacy. The book is a stunning achievement that opens the door for contemporary artists to engage with Burden’s unrealized ideas, and extends rather than upends his status as the art world’s bad-boy daredevil.

-

Book Review: Ballerina Looks Back in Style

Serenade: A Balanchine Story by Toni BentleySerenade: A Balanchine Story

By Toni Bentley

320 Pages

PantheonAs a thin, athletic girl with a springy jump and “not-so-great feet,” Toni Bentley was 11 when she entered the School of American Ballet; she was invited into the New York City Ballet company by George Balanchine at 17, and she performed with them for 10 years, until a hip injury cut her career short. With her prolonged devotion to Balanchine as the backdrop, it is their shared passion for the art form that drives the plot of her new book, Serenade.

Balanchine arrived in America at the behest of eventual NYCB co-founder Lincoln Kirstein, then a visionary and well-connected young Harvard grad. Once arrived, the prolific Balanchine quickly set to work, and the challenging Serenade was the first full-length ballet he composed in his new homeland. The initial performance, in bathing suits and thrown-together costumes, was held in the rain on a makeshift stage in 1934 at a benefactor’s party. Forty years later, author Bentley would first dance the role of one of the four “Russian Girls.” She would go on to perform Serenade 50 times.

Woven throughout the biographical, autobiographical and historical material is a re-creation of the 32-minute, 49-second ballet broken down minute by minute, step by step, from before the curtain rises. We are taken backstage, vicariously rubbing our pointe shoes in rosin and taking places on the stage with Bentley, in a position most uncharacteristic for ballet dancers, parallel. A ballet dancer’s turnout, Bentley postulates, elongates the line, and simultaneously emphasizes and symbolizes the physical and emotional openness—a wrenching apart of body and soul—necessary to adapt to life as a dancer. When—at three minutes, 49 seconds—the entire corps de ballet dramatically pivots from parallel to first, feet at 180º, it evokes a dramatic response: the essence of classical ballet distilled to its most basic premise.

A key element in Serenade is the way in which the emphasis shifts from the traditional model of corps de ballet as mere backdrop against which soloists perform, to one in which each dancer may at any moment strike out into movement which is integral to the structure of the whole. Balanchine’s choreography here clearly displays a revolutionary new spirit of democracy.

If Balanchine’s personal life and human imperfections are a bit glossed over, we may learn more than we ever dreamt of, or perhaps wanted to know, about composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and choreographer Marius Petipa, whose emotional struggles and personal demons are outlined in vivid detail. Bentley’s focus, however, is on Balanchine’s genius, his impact on her own life, and the legacy of the phenomenal ballets that he left behind—Serenade, she asserts, is the finest of them all. Like most of his works, it is both plotless and dense, with suggested narrative and emotional content. He wished to share a story of a man and a woman… or two women, or perhaps three women. Women were his muse and his inspiration, as well as the medium through which he expressed himself. While treading gently on the imprint of Balanchine the man, Bentley makes a striking case for the enduring and profound impact of his brilliant choreography

-

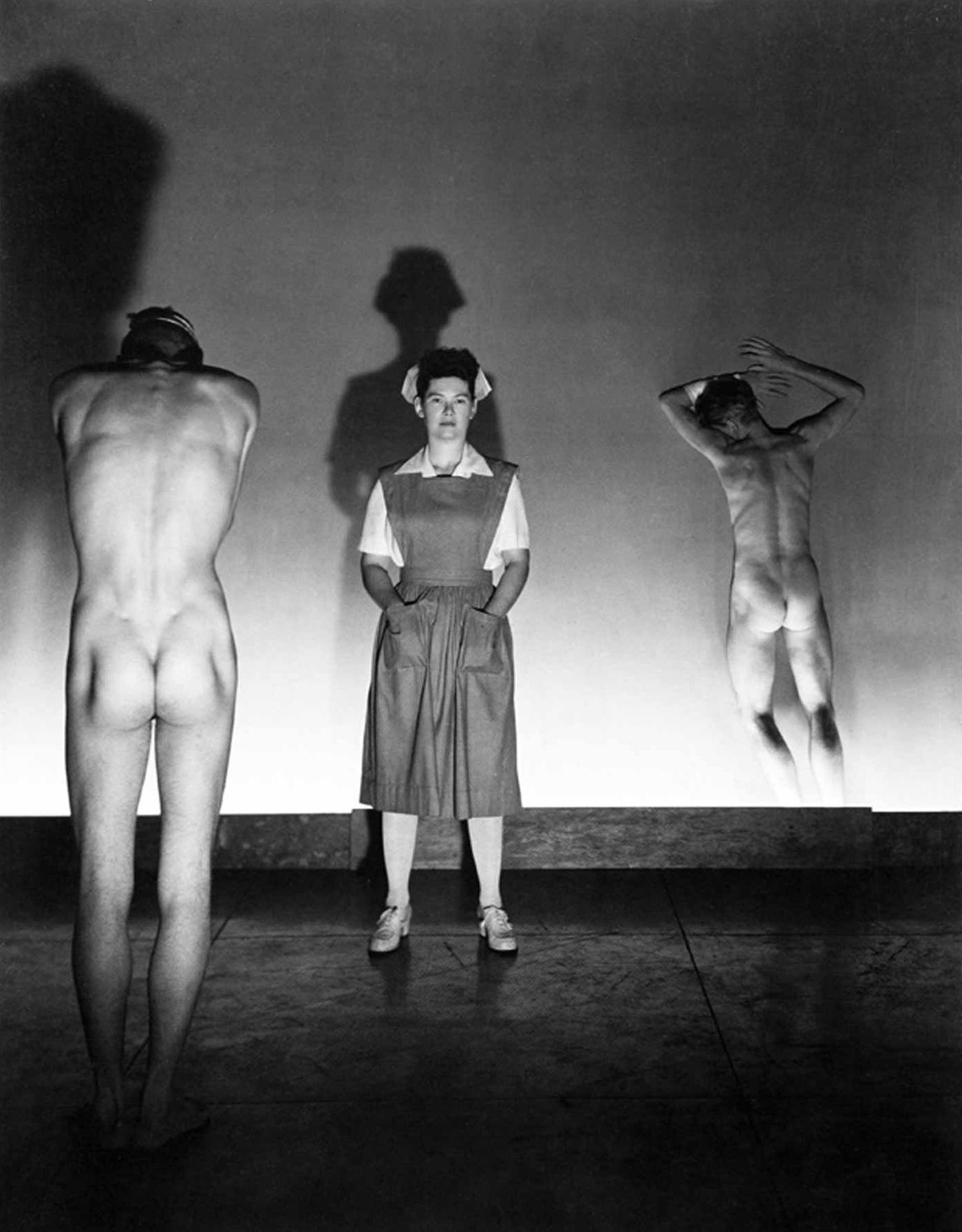

BOOKS: Forbidden Photos

George Platt Lynes’ Daring EyeIn 1981 a new photography monograph appeared that seemed like an artifact from a parallel universe. The cover was a studio shot of a nurse flanked by two nude men. Many of the photos in the book depicted nude men in potentially gay scenarios. It had only become legal to mail this book in the United States ten years earlier. If you were a scholar of the history of photography you might have recognized the photographer’s name from his portrait and ballet photos. But this work caught the world by surprise. Although beefcake photography had been published before in magazines, none of it had the look of something that had been produced by a movie studio. Suddenly people wanted to know who had taken these photos. Unfortunately, the photographer had died 26 years earlier, and hadn’t been famous enough to merit a biography while he was alive. Thanks to an admirable feat of detective work, we now have a pretty detailed account of the photographer’s life.

George Platt Lynes didn’t start by wanting to be a visual artist or photographer. His heart was in the written word. He initially aspired to being a small press publisher and an author. He even owned a bookstore at one point. His original reason for taking photos was to hang them in his bookstore. His love of the written word was on display in the constant flow of letters that he sent and received. On a family trip to France when he was 18, he managed to meet Gertrude Stein. A rich source of material for this book comes from his brother, who wrote an unpublished autobiography of George in the spirit of Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Anybody who is interested in Stein lore will get an interesting perspective of a not yet famous Stein hustling Lynes to get her a publisher (or to publish her himself). George became a regular visitor to Stein’s salons, which caused him to photograph all of the famous people he was meeting. He took what is considered one of the seminal portraits of Stein. Her salon launched him into the right circles, and one of his publishing ventures included a book by Ernest Hemmingway.

Although he was born in 1907, he never seems to have been in the closet. His father was an attorney who became disenchanted with the law and became a minister. He managed to get postings to good neighborhoods, so George grew up in nicer surroundings than a minister’s salary might afford. His mother had a teaching degree, so both parents had experienced higher education. His father loved opera and had worked as an usher during his theological training in order to watch operas for free. As he came into his own, George was an avid attendee of operas, ballets and plays. When he proved to be less overtly manly than his juvenile peers, he would claim to be a Russian prince, whose identity was a highly regarded secret. His parents, sensing that he was different, decided to send him to boarding school in order to offer him some male role models. The school called their approach “muscular Christianity”. Various teachers and classmates compared him to Oscar Wilde, and classmate Lincoln Kirsten remembered him as a “foppish freak”. Once his father was resigned to the fact that his son wasn’t going to pursue a traditional career, he gifted George with his first professional camera.

Cover image of the book. At the tender age of 20 he met and fell in love with author Monroe Wheeler. The problem was that Wheeler was already devoted to another man. George solved the problem by grafting himself onto the existing relationship, making them an early throuple. Once they all decided to live together, their apartment became ground zero for the smart set in Manhattan. The relationship lasted for nearly 20 years. His earliest photographic work was portraits. He had access to a who’s who of the mid 20th century, and his social whirl always had a bit of calculation about who might sit for a portrait (or take off their clothes for a more private photo. He convinced Tennessee Williams and Yul Brenner to pose naked) He paid the bills by doing fashion photography, and his ballet photography brought in income. Money was always an issue. First his father and then his younger brother were often called upon to keep the wolf from the door. It can be head spinning to read that while he is up to his eyeballs in debt, he needs to run home and change into his top hat and tails for the opera.

Eventually the IRS ended his long streak of good luck. In 1952 the entire contents of his studio were auctioned off to pay back taxes. (Richard Avedon ended up with his studio) His younger brother brought in proxy bidders to buy back his camera and essential equipment. But he never recovered his mojo, and died within three years of lung cancer. Sensing his own mortality, he made arrangements to place the nude photo work with the Kinsey Institute.

This book is rich in details about his life and the world that produced him. It is the sort of book that you can open to a random page and be caught by some detail that will have you racing to Google to learn more. There are photos throughout the book that offer relevant visuals. The footnotes are copious and often fascinating in their own right. For anybody looking to study or recreate gay life in the mid 20th century, this is a deluxe road map.

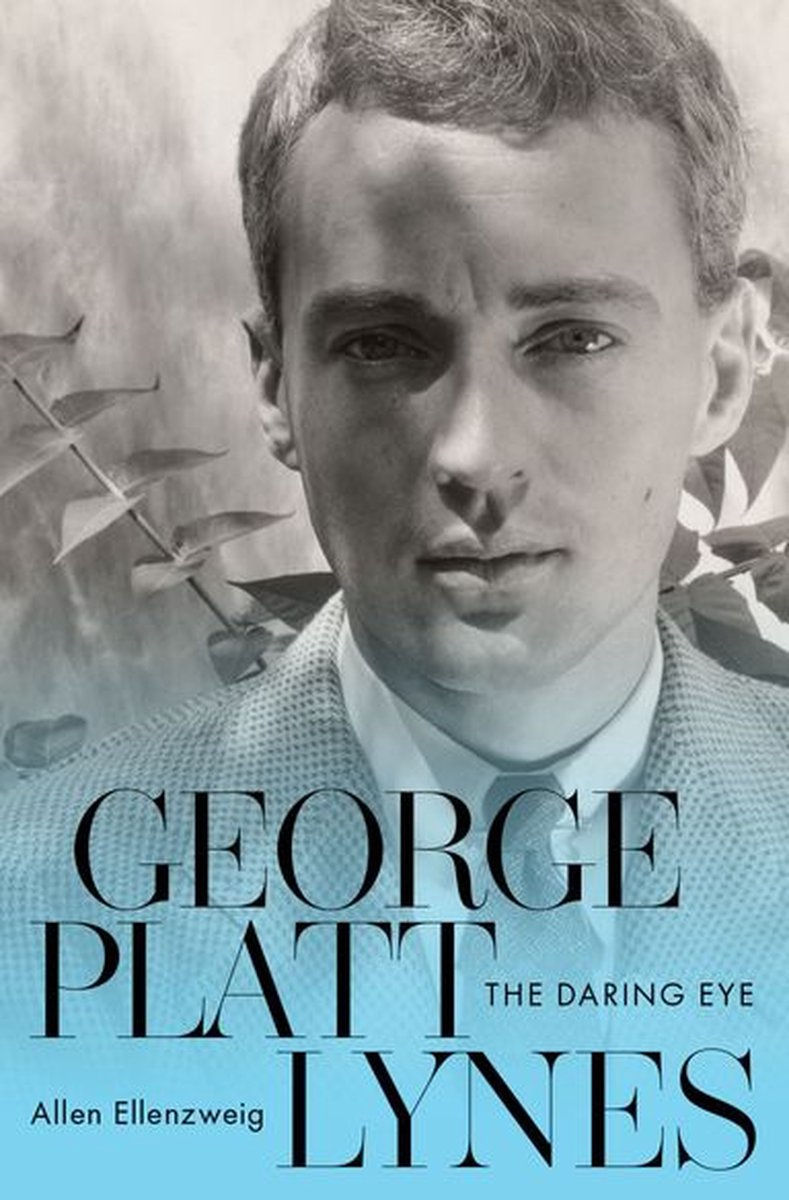

George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye

by Allen Ellenzweig

664 pages, illustrated

Oxford University Press

-

René Magritte and the First Art Gang

Book Review of “Magritte: A Life”Magritte: A Life

By Alex Danchev

439 pages, illustrated

Pantheon Books

When an artist achieves the kind of iconic status where they are known outside of the Art World, there can often be a tendency to codify their myth into something that might pass the Elevator Pitch Test. René Magritte has suffered more than others from this oversimplification. A new biography shows us that still waters run dangerously deep. Although the author died before the book was completed, enough finished material and notes were left for an astute writer to complete the last chapter without a noticeable shift in tone from the rest of the book, and there are copious footnotes.

Magritte’s father made and lost two fortunes; he chased skirts and gambled; he hung pornographic prints on the walls of their house and taught the children to blaspheme. He fancied himself a hypnotist: the library that young René grew up with was all books on mesmerism and spiritualists. With his brothers, René formed a gang that was the terror of the neighborhood; they destroyed toilets with yeast and possibly robbed graves. One of the young Magreitte’s major influences was the work of the filmmaker Louis Feuillade, whose serials about glamorous criminal gangs inspired the activities of his own gang.

When he was 13, René’s mother drowned herself, and his father married his mistress. A year later, Magritte decided to become a painter. Although he had a high regard for Max Ernst, he preferred the company of writers. In fact, he did a lot of writing over the years, including art theory, philosophy and detective stories (unfortunately, none of this writing is currently available in English). He also collaborated with writers for subject matter and titles for paintings.

René Magritte, L’Homme au chapeau melon (The Man in the Bowler Hat), 1964. New York, Collection Simone Withers Swan. Magritte’s work didn’t start selling immediately. In the late 1920s he was able to arrange a stipend from a group of collectors, who would receive paintings in exchange. When the stock market crash of 1929 wiped out his investors financially, a giant cache of his unsold paintings was dumped on the market for about 60 francs each. He was briefly affiliated with the Surrealists until André Breton expelled him. Despite that, Breton remained an avid collector of his work.

When Magritte started to be included in group shows, it was not uncommon for his work to be displayed behind an adults-only curtain among such other “upsetting” artists as Dalì and Balthus. When he wanted to produce a monograph during the Occupation he financed the project by forging art. One of these forgeries made it into his Catalog Raisonné as an interpretation of a Titian. He had combined elements from two Titian paintings into a new work. He even briefly forged currency.

Magritte’s adventures in the demimonde help us to understand that he was not just a bourgeois painter of clever jokes (a common misconception during his lifetime). Throughout his life, he always had a gang. In the 1950s they staged tableaux vivantes and made movies, and this biography serves as a useful roadmap to an aspiring publisher or media company looking for “lost” texts, or underground films.

The book itself is a lavish object. In addition to the sections of color plates, there are rare photographs throughout. Along the way we meet writers and artists who have fallen out of favor. Even if Magritte is not your primary interest, it’s a great snapshot of the milieu and period that it covers.

-

Book Review: STREET ART & SOCCER

“The Chosen Few: Aesthetics and Ideology in Football Fan Graffiti and Street Art” By Mitja VelikonjaThe Chosen Few: Aesthetics and Ideology

in Football Fan Graffiti and Street ArtBy Mitja Velikonja

176 pages

DoppelHouse Press

Graffiti and street art are often considered synonymous since they affect the urban environment in similar ways. But graffiti is onomastic: the essential purpose is to advertise one’s presence; it’s the big “I am” that challenges metropolitan anonymity. That is also achieved with latrinalia, slogans and phrases that serve as necessary disruption of daily life. Graffiti is a platform for outsider political and social activism among those who consider themselves silenced or purposefully omitted from larger societal colloquies.

Unlike street art, which is generally sanctioned and can remain an element of the street for an extended amount of time, graffiti is illegal and temporary. Consequently, some writers and sticker-bombers prefer membership in a group from which graffitaro can anonymously promote that to which they pledge allegiance. In Europe, soccer fans known as ultras typically design and produce their own stickers, pasteups and wall pieces promoting their favorite Football Club (FC). These remarkable DIY designs are featured in Mitja Velikonja’s scholarly illustrated book The Chosen Few: Aesthetics and Ideology in Football Fan Graffiti and Street Art, which examines the relationship between European soccer teams and their graffiti-oriented, street activist fans.

Velikonja posits that sticker bombing and stenciling reveal how soccer fan graffiti is never ideologically neutral or apolitical, and the statements being made often cover more than a single issue. The observation that soccer is a “means by the powerful to pit workers against workers in competition and as a potential tool for nationalism” means that in some cases the graffiti is about intense societal differences as well as sports rivalry. In The Chosen Few, Velikonja discusses such direct display of political preferences and values, as well as fans’ self-image and the recognizable aesthetics of their stickers or stencils.

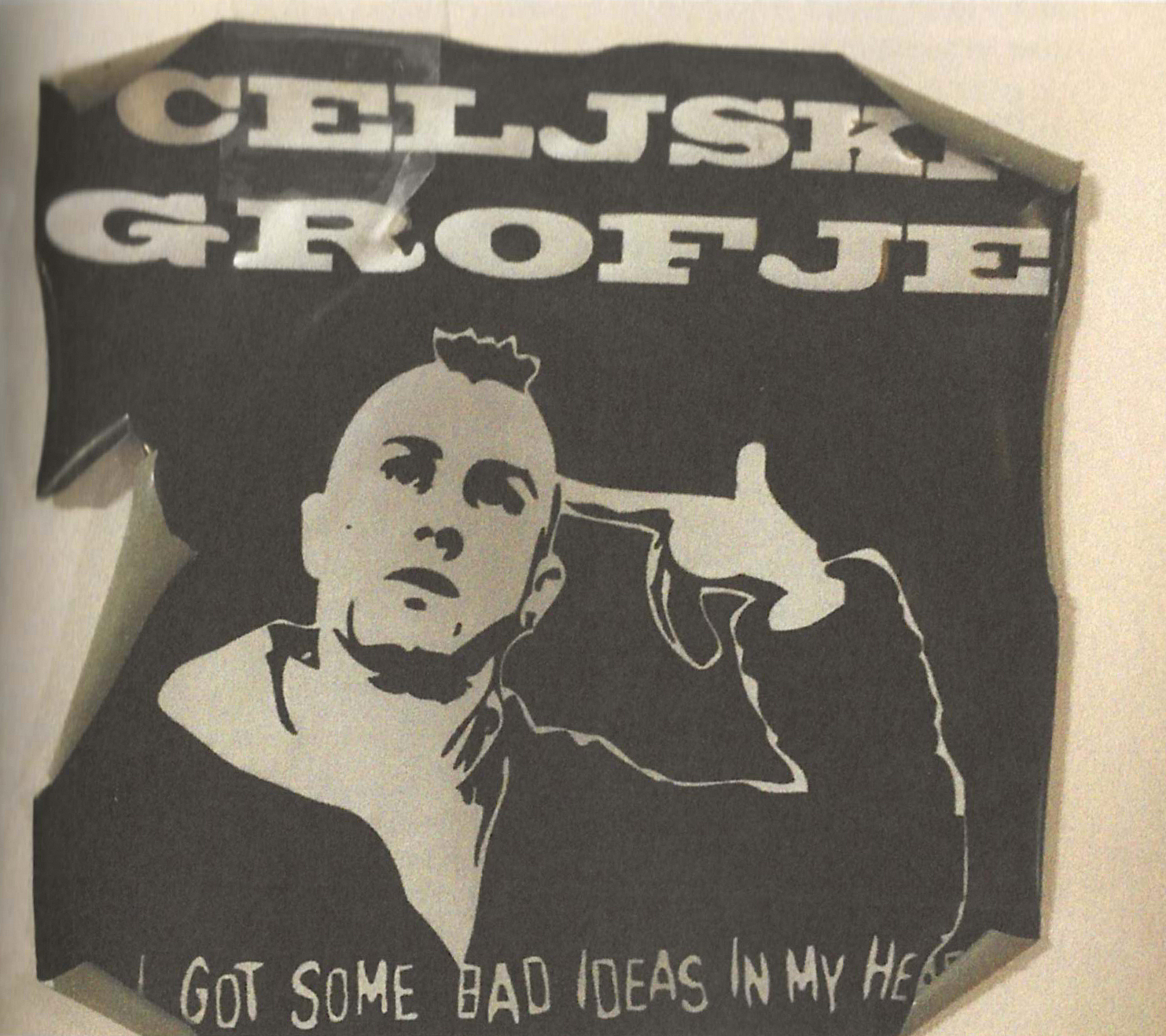

The Chosen Few book cover, image by Tauras Stalnionis Much of the graffiti and street art in The Chosen Few relies on altered versions of iconography already familiar to the public. This ensures that passersby, attracted by the striking image, will examine the sticker long enough to parse that it’s promoting a specific soccer team. For example, one sticker bomber fan of Slovenian Celje Football Club uses a metonymic image of Travis from the film Taxi Driver and the line “I got some bad ideas in my head” to express their disdain for other teams and non-fan society in general. The negative side of this “economy of means” is that present-day advocates of the extreme right resort to displaying swastikas and other Nazi symbols to promote their favorite soccer club, even though ironically, that team might have nothing to do with such ideology.

Although graffiti is an ancient method of visual communication, it is only in the last 20 years that it has matured to become a familiar element of self-expression in the urban arena. Consequently, Velikonja’s analyses are an essential addition to any discussion about the connection between football and graffiti, as well as its effect on social affairs in the streets. To be sure, an abundance of facts is necessary to support a thesis, but in this case it weighs down the fascinating nature of the subject. Velikonja’s exhaustive research makes The Chosen Few so dense that, while a compelling read, it could use a little more about markers and less about Marx.

-

Books: Jona Frank and John Divola

SoCal Photographers Cover It AllJona Frank’s new book, Cherry Hill, came out this spring almost simultaneously, but coincidentally, at the same time as another book, Terminus, by another SoCal photographer, John Divola. The coincidence is as fortunate as it is fortuitous because their subjects and approaches could not be more different. Even the geography in which they worked is far-flung, with Frank’s attention focused nearby on a Santa Monica lifestyle, while Divola’s ranges northeast to an abandoned military base in Victorville, CA. Though Divola’s is the more esoteric work, each photographer is at the top of his/her game.

In Frank’s Cherry Hill (above) the photographs are heartfelt but amusing. They could be straight out of a soap opera, if the episodes were soulful rather than facetious. What she has created is more of a sitcom. Movie actress Laura Dern plays a mom who is raising a daughter in a vintage Santa Monica home. We see the tussle between mother and daughter as the latter progresses from a bawling infant to an obstreperous 23 year old. Along the way, she assumes, naturally, that she’s much smarter, better, etc., than her mom. Dern sets the pace for the mutual frustration between mother and child as the daughter grows up.

from Terminus page 23, © John Divola John Divola’s Terminus is a book larger in format than Frank’s but with far fewer pages. All these photographs were, like the one above, made in abandoned houses on the closed George Air Force Base in Victorville. All were, Divola tells us, “exposed as b&w negatives in 2016.” Each looks down a narrow hallway toward a wall on which

Divola has spray-painted a black, sometimes mishappen circle. The deterioration that the hallways reveal is pitted against the indeterminant abstraction of the black circles. Little by little the camera advances down these halls until the image becomes just a vertical, black space—an inescapable end point. -

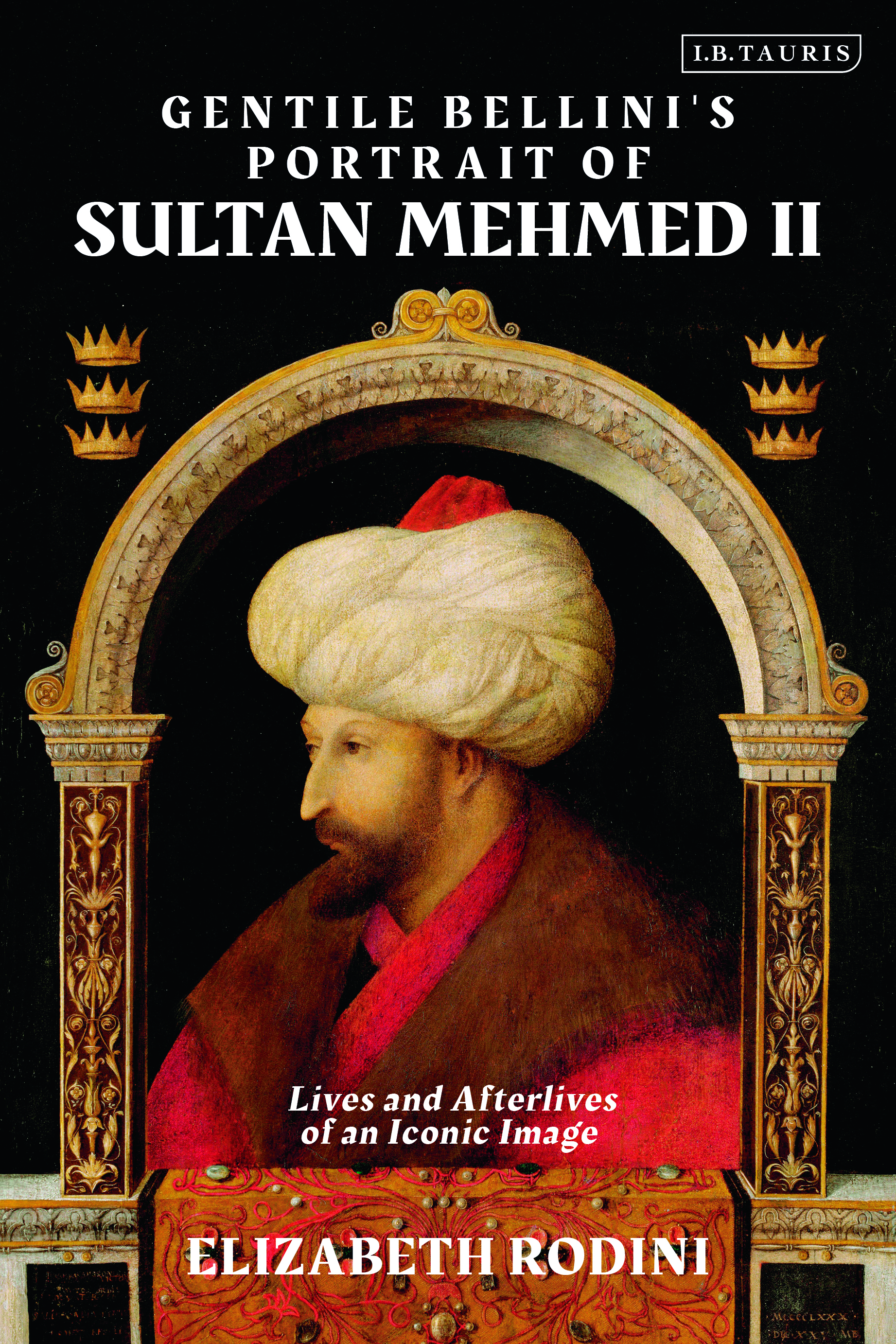

Book Review: Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II By Elizabeth Rodini

ABJECT OBJECTElizabeth Rodini’s Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II (2020) landed on my radar through meeting Rodini last year at the American Academy in Rome, where she is the Andrew Heiskell Arts Director. Rodini’s recent object biography investigates a number of intriguing and complex issues. Gentile Bellini, brother of the better-known Giovanni, was a Venetian artist. In 1479, he was commissioned to travel to Istanbul to paint a portrait of the Sultan, Mehmed II. This Renaissance portrait of an Ottoman sultan has gained a broad mystique, its legend perhaps eclipsing the actual substance of the canvas itself.

We may follow Rodini into the subterranean vaults of London’s National Gallery, where she finally encounters the portrait she has been exhaustively researching for so long …in a state of neglect, an object so altered and eroded as to bear little resemblance to its original state. This abject object had been the focus of intense strife and controversy, fought over for centuries.

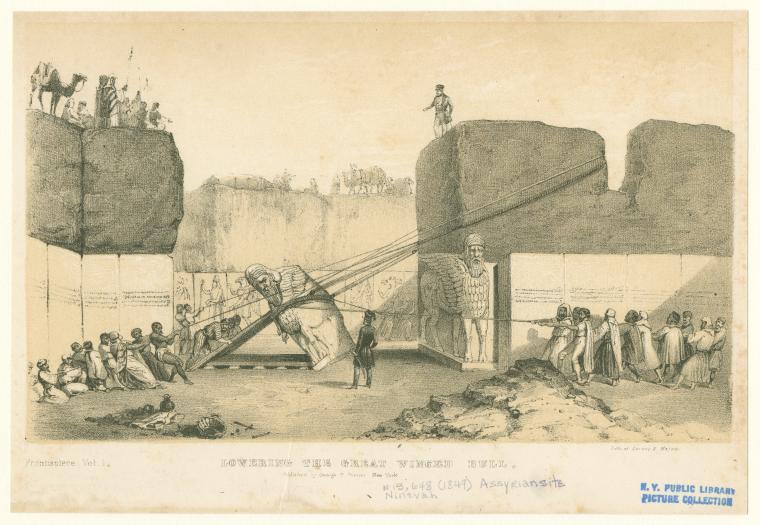

Lowering the Great Winged Bull, lithograph, frontispiece to Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, (London, 1849), The New Your Public Library, Digital Collections. Rodini brings this ostensibly dry and academic subject to life with the intensity of a gripping mystery novel…”Who done it?”

Cultural patrimony—the premise that artworks belong in the culture, often the country, where they were made—was a budding idea in 1912 when the owner of the painting, Enid, widow of collector and archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, passed away. The Layard collection, then housed in a palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal, was willed to her nephew, and London’s National Gallery. Before those parties could resolve who might have rights of ownership, they needed to get the painting to England—no small feat with Italy clinging to its treasured art objects.

This question of individual’s rights of ownership is a challenging one: Is it better to support the claims of individuals’ (or institutions) to private ownership of artwork, or will the broader good be served by placing the artwork in a setting deemed more culturally appropriate?

The Elgin/Parthenon Marbles are the “litmus test” for this issue, according to Rodini. Lord Elgin brought them from Greece to the British Museum in the early 19th century, where they have now resided for over 200 years. Greece, reasonably arguing that they were looted from the Parthenon in Athens, demands their return. The dispute has raged for centuries; Byron was among the first to condemn the looting. Once this is eventually settled, it may tip the scales for similar repatriation cases across the globe.

After James Fergusson, color lithograph, The Palaces of Nimroud Restored, color lithograph in Austen Henry Layard, The Monuments of Ninevah, 2nd Series (London, 1853), pl. 1. The New York Public Library, Digital Collections. Rodini takes a measured stance overall, weighing the value of the universality of priceless antiquities against the need to redress past injustices. Her description of studying an image in 2015 of an Assyrian winged bull in the British Museum, concurrent with reading news stories of ISIS defacing with power tools a nearly identical ancient sculpture in Iraq as part of a purge of imagistic artwork, definitely provides food for thought. Still, no excuses can be made for the colonialist and Orientalist impulses of these early plunderers, and repatriation will no doubt be one of the key challenges facing museums as they research the provenance of objects in their collections.

Rodini’s thoughtful work offers us an eye-opening window into many enticing, interwoven and labyrinthine realms.

Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II:

Lives and Afterlives of an Iconic ImageBy Elizabeth Rodini

224 pages

I.B. Tauris