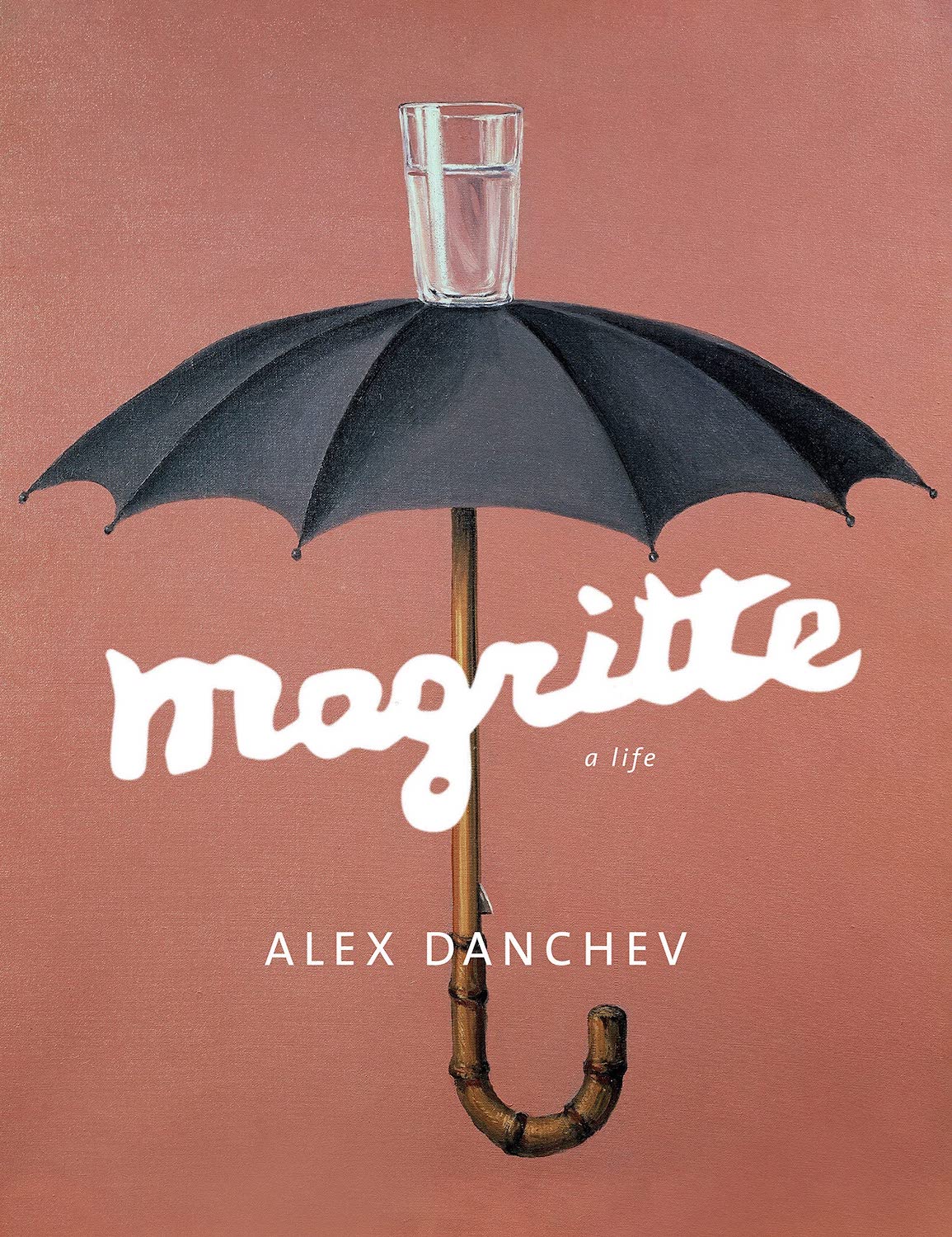

Magritte: A Life

By Alex Danchev

439 pages, illustrated

Pantheon Books

When an artist achieves the kind of iconic status where they are known outside of the Art World, there can often be a tendency to codify their myth into something that might pass the Elevator Pitch Test. René Magritte has suffered more than others from this oversimplification. A new biography shows us that still waters run dangerously deep. Although the author died before the book was completed, enough finished material and notes were left for an astute writer to complete the last chapter without a noticeable shift in tone from the rest of the book, and there are copious footnotes.

Magritte’s father made and lost two fortunes; he chased skirts and gambled; he hung pornographic prints on the walls of their house and taught the children to blaspheme. He fancied himself a hypnotist: the library that young René grew up with was all books on mesmerism and spiritualists. With his brothers, René formed a gang that was the terror of the neighborhood; they destroyed toilets with yeast and possibly robbed graves. One of the young Magreitte’s major influences was the work of the filmmaker Louis Feuillade, whose serials about glamorous criminal gangs inspired the activities of his own gang.

When he was 13, René’s mother drowned herself, and his father married his mistress. A year later, Magritte decided to become a painter. Although he had a high regard for Max Ernst, he preferred the company of writers. In fact, he did a lot of writing over the years, including art theory, philosophy and detective stories (unfortunately, none of this writing is currently available in English). He also collaborated with writers for subject matter and titles for paintings.

René Magritte, L’Homme au chapeau melon (The Man in the Bowler Hat), 1964. New York, Collection Simone Withers Swan.

Magritte’s work didn’t start selling immediately. In the late 1920s he was able to arrange a stipend from a group of collectors, who would receive paintings in exchange. When the stock market crash of 1929 wiped out his investors financially, a giant cache of his unsold paintings was dumped on the market for about 60 francs each. He was briefly affiliated with the Surrealists until André Breton expelled him. Despite that, Breton remained an avid collector of his work.

When Magritte started to be included in group shows, it was not uncommon for his work to be displayed behind an adults-only curtain among such other “upsetting” artists as Dalì and Balthus. When he wanted to produce a monograph during the Occupation he financed the project by forging art. One of these forgeries made it into his Catalog Raisonné as an interpretation of a Titian. He had combined elements from two Titian paintings into a new work. He even briefly forged currency.

Magritte’s adventures in the demimonde help us to understand that he was not just a bourgeois painter of clever jokes (a common misconception during his lifetime). Throughout his life, he always had a gang. In the 1950s they staged tableaux vivantes and made movies, and this biography serves as a useful roadmap to an aspiring publisher or media company looking for “lost” texts, or underground films.

The book itself is a lavish object. In addition to the sections of color plates, there are rare photographs throughout. Along the way we meet writers and artists who have fallen out of favor. Even if Magritte is not your primary interest, it’s a great snapshot of the milieu and period that it covers.