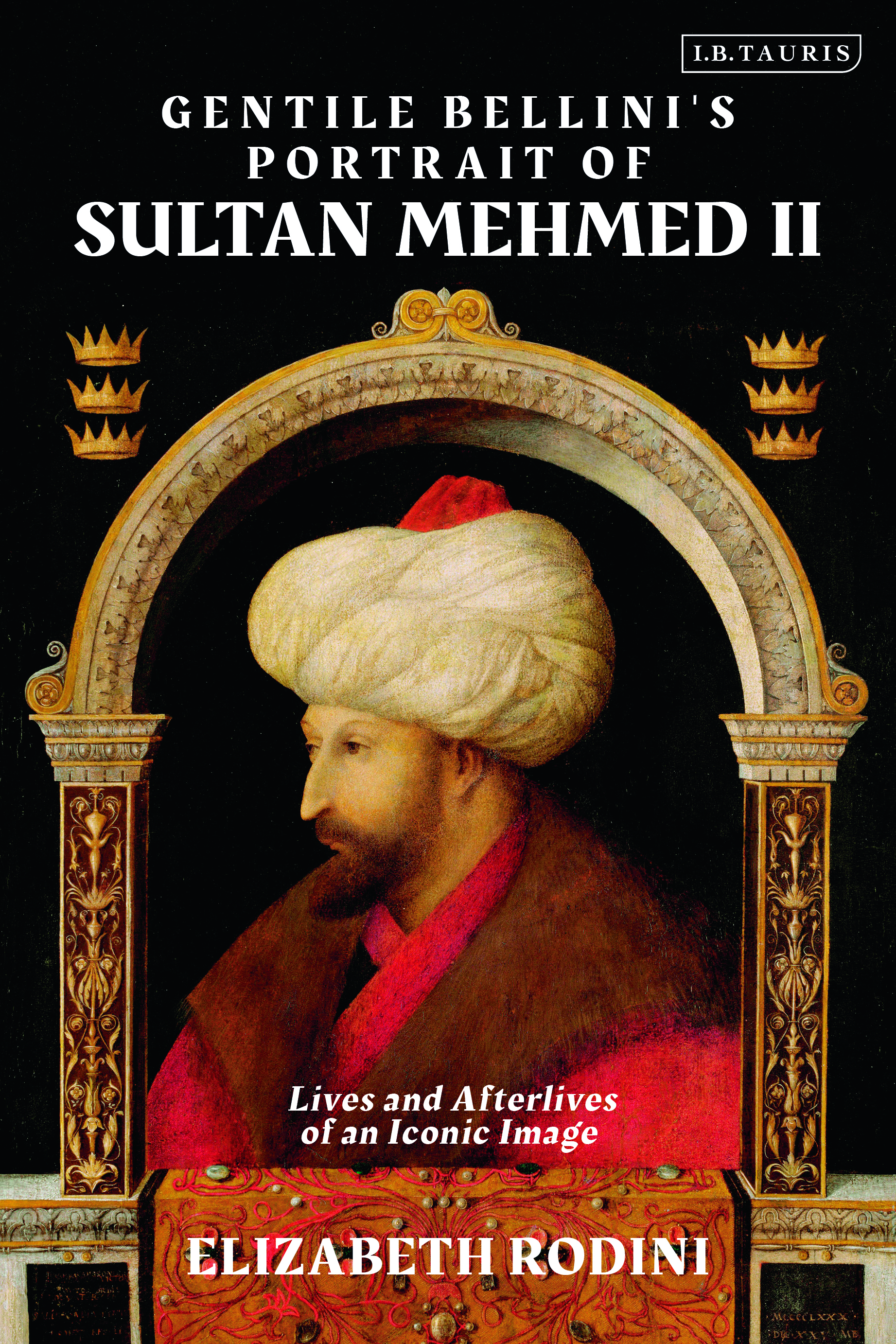

Elizabeth Rodini’s Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II (2020) landed on my radar through meeting Rodini last year at the American Academy in Rome, where she is the Andrew Heiskell Arts Director. Rodini’s recent object biography investigates a number of intriguing and complex issues. Gentile Bellini, brother of the better-known Giovanni, was a Venetian artist. In 1479, he was commissioned to travel to Istanbul to paint a portrait of the Sultan, Mehmed II. This Renaissance portrait of an Ottoman sultan has gained a broad mystique, its legend perhaps eclipsing the actual substance of the canvas itself.

We may follow Rodini into the subterranean vaults of London’s National Gallery, where she finally encounters the portrait she has been exhaustively researching for so long …in a state of neglect, an object so altered and eroded as to bear little resemblance to its original state. This abject object had been the focus of intense strife and controversy, fought over for centuries.

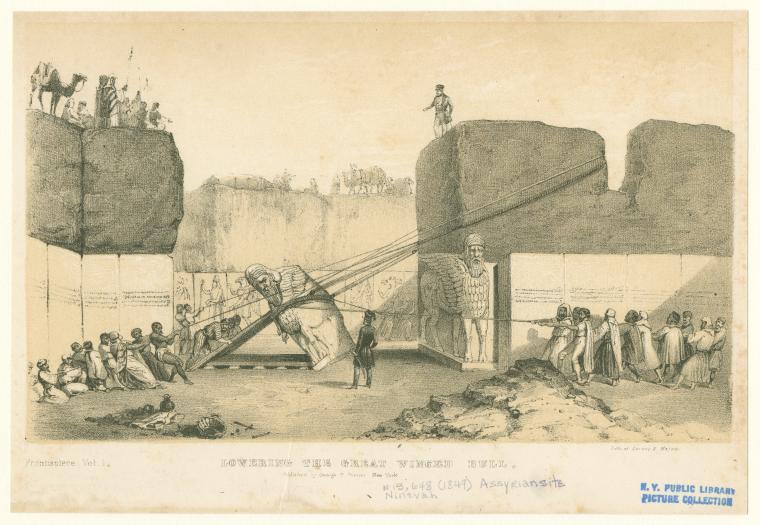

Lowering the Great Winged Bull, lithograph, frontispiece to Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, (London, 1849), The New Your Public Library, Digital Collections.

Rodini brings this ostensibly dry and academic subject to life with the intensity of a gripping mystery novel…”Who done it?”

Cultural patrimony—the premise that artworks belong in the culture, often the country, where they were made—was a budding idea in 1912 when the owner of the painting, Enid, widow of collector and archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, passed away. The Layard collection, then housed in a palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal, was willed to her nephew, and London’s National Gallery. Before those parties could resolve who might have rights of ownership, they needed to get the painting to England—no small feat with Italy clinging to its treasured art objects.

This question of individual’s rights of ownership is a challenging one: Is it better to support the claims of individuals’ (or institutions) to private ownership of artwork, or will the broader good be served by placing the artwork in a setting deemed more culturally appropriate?

The Elgin/Parthenon Marbles are the “litmus test” for this issue, according to Rodini. Lord Elgin brought them from Greece to the British Museum in the early 19th century, where they have now resided for over 200 years. Greece, reasonably arguing that they were looted from the Parthenon in Athens, demands their return. The dispute has raged for centuries; Byron was among the first to condemn the looting. Once this is eventually settled, it may tip the scales for similar repatriation cases across the globe.

After James Fergusson, color lithograph, The Palaces of Nimroud Restored, color lithograph in Austen Henry Layard, The Monuments of Ninevah, 2nd Series (London, 1853), pl. 1. The New York Public Library, Digital Collections.

Rodini takes a measured stance overall, weighing the value of the universality of priceless antiquities against the need to redress past injustices. Her description of studying an image in 2015 of an Assyrian winged bull in the British Museum, concurrent with reading news stories of ISIS defacing with power tools a nearly identical ancient sculpture in Iraq as part of a purge of imagistic artwork, definitely provides food for thought. Still, no excuses can be made for the colonialist and Orientalist impulses of these early plunderers, and repatriation will no doubt be one of the key challenges facing museums as they research the provenance of objects in their collections.

Rodini’s thoughtful work offers us an eye-opening window into many enticing, interwoven and labyrinthine realms.

Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II:

Lives and Afterlives of an Iconic Image

By Elizabeth Rodini

224 pages

I.B. Tauris