Your cart is currently empty!

Category: MAY-JUNE 2021

-

From the Editor

May-June, 2021; Volume 15, issue 5

Dear Reader,

Spring is in the air, skies are blue, daffodils are blooming and the art galleries are opening up. Makes you want to paint or write poetry or string along happy clichés! Yes, the world—at least here in Los Angeles—seems to be emerging from a long dark year. And while it might be premature to starting singing Happy Days Are Here Again—I’m pickin’ up good vibrations.

We’ve got people spending their stimulus checks, and just wanting to splurge. Galleries are responding to that, just like any other business that is reopening. Though the galleries (as opposed to museums and college art galleries) still operated during the pandemic, collectors weren’t as eager to spend money in an uncertain economy.

What we learned is that we didn’t really need money to keep the art world going. It never stopped, stalled or even slowed down. Of course I’m referring to the lowest common denominator—the artists themselves. The pandemic provided plenty of time for artists to delve deeper into their art, and apparently they did. Many gallery exhibitions right now are filled with art made during the last year.

Most artists don’t create work to make money; they know that they would be deluded to think otherwise. Most artists create because it’s how they function and survive. Take me, for instance: I knew I wanted to be an artist when I was a child. I wasn’t taken to art museums, I didn’t have an aunt that painted; I wasn’t even encouraged even though it was clear that I had talent. I begged my parents to buy me coloring books. I will never forget the bright neon colors that came with my Bullwinkle glitter paint-by-number set—on black velvet! I gave it to my grandmother, and I’m sure she eventually threw it away.

But it didn’t matter. I just kept on making art. I won contests in school art shows: a psychedelic painting of my cat in a tree was held up in class as an example of what a good painting should look like. My college professor kissed me when he saw the finished AbEx painting I set up for class critique.

I wasn’t ready to call myself an “artist,” though—it felt too elitist. Making art didn’t feel like work, so it was a privilege to make art all day. And was I really contributing to society?

Those questions haunted me as I dared to continue my higher education in art. This issue explores that very conundrum. Are artists the property of galleries? And what about NFTs? Is that just another scam to appeal to people with so much money that we have to invent ways for them to spend it? All in the name of art?

How relevant is art to today’s world? With the continuing disparity of The Haves (Lots) and The Have Nots, artists are looking toward closing up that enormous gap. Our theme, Private Property, explores how artists are addressing this and maybe it’s time the old system got shaken up. That would be as welcome as the flowers in May, and isn’t that what art is all about?

-

Shoptalk

LA Museum Update, Digital Art Happenings, In Memory: Simone GadDigital Art Happening

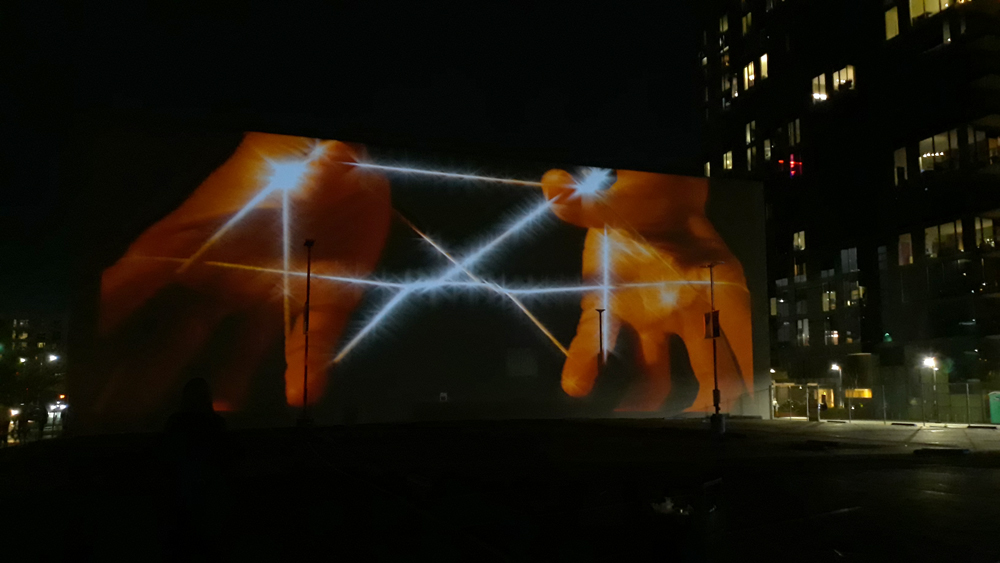

In April there was a moment when Yours Truly realized we were finally, at long last, emerging from the pandemic that has shut us in for over a year. It was Saturday night, and we were lured downtown by “LUMINEX: Dialogues of Light,” a one-night art happening of digital art projected onto building walls in DTLA. During COVID-time I’ve driven through these streets on various missions, and they were so empty it was apocalyptic. But tonight, lower Broadway was percolating with barhoppers and diners and, as darkness fell, art fans and those who had been pent up too long.

Sarah Rara, Perfect Touch, 2021, photo by Scarlet Cheng We started our rounds a little before the 7:30 official time—first stop was Sarah Rara’s “Perfect Touch 2021.” In a parking lot at 11th and South Olive, there was towering projection equipment and a handful of people, including guards and tech who were running the show. It was dusk, and we were told there was another half of the piece on the “other” side of the building—that is on the other side of the block. By the time we returned to look at the first piece again, it was dark, and there was now a crowd enjoying the sight of gigantic hands playing cat’s cradle—the string burning with light—and a voice reading a poem so aptly addressed to this strange, strange year: “The year of distance, the year of loss, the lost year,” the woman intoned, “The year of acknowledging fragility, interconnectedness.”

I think we will soon be seeing more work about what we’ve been through. It’s been a traumatic time, our shared annus horribilis—and we need to work it out through art: all forms of art, including writing and performance. And it was not only disease that captured us, but also a megalomaniac in power and his minions, bent on destroying the fabric of our civil life.

That night in DTLA we saw mesmerizing op-arty work by Nancy Baker Cahill and cascading images by Carole Kim, and a couple others. By 9 PM there were throngs of people on the sidewalks moving from site to site—mostly young and mostly elated to be out and about. Around us, new buildings were sprouting on nearly every block, some finished, others almost finished. What’s so surprising is that many are residential, housing for the new DTLA Urbanites. For some, the evening had just begun.

Installation photograph, Yoshitomo Nara, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2020, art ©Yoshitomo Nara, photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA. LA Museums (Finally) Reopen!

Museums also began to announce their reopenings in April, hooray! LACMA had a long list of exhibitions scheduled to open last spring and summer but, alas, did not. The biggest and probably most popular is the Yoshitomo Nara retrospective—he of the big-eyed girls holding little knives. To this day I never know what to make of his work—which has strong cartoony kitsch elements that play on its own commercial success. Yes, he is one of the most successful Asian artists today—in 2019, his painting Knife Behind Back sold for $24.9 million at Sotheby’s. I did enjoy looking at Nara’s early work, as he searches for his central themes. There is a reconstructed studio filled with drawings and small collectibles, which we peer into through windows. Then, as his canvasses grow in size and his brush becomes more impressionistic—as he turns away from his roots in line and drawing—he starts to lose me.

The Getty Villa has just reopened, with the exhibition “Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins.” I found the smaller show down on the main level, “Assyria: Palace Art of Ancient Iraq,” far more memorable. The subject matter is more focused (bas-reliefs from Assyrian palaces of the 9th to 7th centuries BC) and the images are so vivid, even brutal, in their storytelling: men hunting lions, soldiers storming battlements, kings lording it over everyone. These are on loan from the British Museum.

Also open are the Hammer (“Made in LA”), the Huntington (“Made in LA’s” second venue), California African American Museum (Sula Bermúdez-Silverman and Nikita Gale), and Forest Lawn Museum at Forest Lawn Glendale. Yes, the cemetery has a museum, and it’s currently featuring a terrific survey of work from noted stained-glass maker Judson Studios, based in Highland Park.

Simone Gad, photo by Lynda Burdick. OBITUARY

Saved by Simone Gad (1947–2021)

Simone Gad understood the tenuousness of appearances, their material possession and assertion. Her work as an artist was a conscious, deliberated and obsessive retrace of those assertions, an insistence upon their value and significance long after the fade-to-black, whether material or psychological (or for that matter cinematic—Hollywood actor and performer that she remained to the end). Among contemporary LA artists, she was a poète maudite, her work poised on a razor’s edge between redemption and remembrance; and she embraced it in full, transmuting loss and desperation into affirmation, affection, joy, mercy and defiance.

—Ezrha Jean Black

Please visit www.artillerymag.com/saved-by-simone-gad-and-other-souvenirs/ for a full read on the remembrance of Simone Gad.

Comings and Goings

Frieze LA is cancelled, finally. It’s been reported that they had planned to have galleries showing art in various available spaces around town—Paramount Studios, its usual haunt, was already booked to the gills with productions trying to play catch-up after COVID delays. This meant lots of driving for Angelenos (who already drive too much). The wonky logistics of all this apparently collapsed a scheme which would have been pretty challenging, even in the best of times. They’ll be coming back in February 2022 though, in a tent next to the Beverly Hills Hilton.

It was just a matter of time before New York mega-gallerist David Zwirner realized he had to open an outpost in Los Angeles—and Artnet reports he’s found a space near Deitch Projects in the West Hollywood area. LA galleries are making a move too—lots of well-located retail space is open around the city (the unfortunate fallout of COVID and the crippled economy). Moran Moran is moving to Western and Melrose. Luis De Jesus is leaving Culver City for DTLA and Lowell Ryan is moving from West Adams to West Washington Boulevard, in a building with a roomy courtyard. It’s always good to have outdoor space in LA, and of course so very useful for receptions and gatherings.

MENTAL HEALTH

May is Mental Health Awareness Month, and the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health is sponsoring a month-long series of free programs and events highlighting the healing powers of art and connection. In its fourth year, WE RISE includes Art Rise with 21 art projects, Community Pop-Ups with over 50 local activities, and a Digital Experience, which can be enjoyed the usual way—virtually.

At this point, I’m especially keen on the RL experiences. Grand Park in DTLA, for example, will be home to “Grand Park’s Celebration Spectrum“ by dublab, in collaboration with Tanya Aguiñiga and curator Mark “Frosty” McNeill. Art installations and programming will “create space for all the missed celebrations in Los Angeles during the last year,” says the press release. Check out the festivities at www.werise.la.

-

The NFT Craze

Art BriefThe digital artist known as Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million in cyptocurrency at Christie’s auction in March, 2021. The media treated this grotesque sale as if it revolutionized the art world, but if we separate reality from the hysterical hype, it clearly has not. An NFT stands for a “non-fungible token”—probably the most ridiculous acronym ever invented by digital geeks. An NFT is nothing more than a token on a shared digital ledger in the never-ending continuum known as blockchain. I’m not an expert on blockchain; however, suffice it to say, the owner of an NFT can signify his ownership by obtaining a token, or time-stamp in a digital ledger that constitutes a blockchain.

It’s important not to confuse ownership of an NFT with ownership of a copyright which is governed by copyright law. Common law copyright automatically attaches upon the artist’s creation of the work and statutory copyright is established by a filing with the US Copyright Office. The vast majority of the time when an artwork is sold the artist retains the copyright. The artist may also license the copyright if, for example, he or she wishes to merchandise an artwork’s image.

An owner of an NFT does not own the digital artwork or the copyright that attaches to it (ownership is retained by the digital artist). The buyer simply owns the NFT of the first edition of the digital file, but nothing else. Is NFT a con? I leave it to those who have read about the 17th-century Tulip bulb craze in the Netherlands to decide.

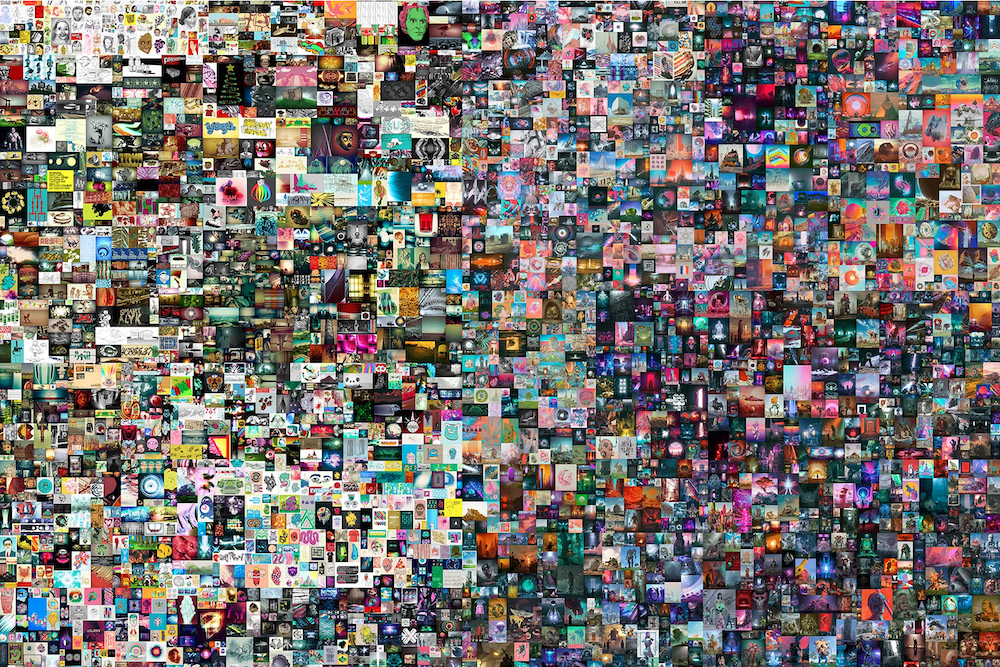

Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) had a successful career as a graphic designer of video games when he decided he would create a new digital image every day for 5,000 days. The digital file which set the record at Christie’s for a NFT contained all of those images and was titled Everydays: The First 5,000 Days. I’m not going to quibble about whether digital art itself is “art.” As far as I’m concerned, it is. The problem is that the NFT of a digital file is a digital ledger entry which does not constitute an artwork.

Over the last few years NFTs have become things of value and can be bought or sold online. In fact, prior to the auction of The First 5,000 Days, Beeple sold numerous NFTs of still digital images he created, as the market for NFTs got red hot. Many of the images making up the The First 5,000 Days and other Beeple digital works are freely available to view online (featured here).

A few weeks before The First 5,000 Days was sold, an NFT of Nyan Cat, a ubiquitous meme of a flying cat with a pop-tart body, was sold by its creator for the equivalent of $580,000 in cryptocurrency. Recently, there has been a frenzy for NFTs of short clips of NBA stars making spectacular dunks or blocks. A digital token of LeBron James blocking a shot went for $100,000 in January. A company called NBA Top Shot has made a market in NFT sports clips achieving $43 million in sales in January, 2021, according to The New York Times.

Stills from Kate Moss’s NFTs. Anything digital can be an NFT. The Times reports that Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey sold his first tweet for the equivalent of over $2 million in crypto. The insanity reached new heights in April as Vogue reported that super-model Kate Moss said she was selling NFTs labeled “Kate Sleeping” and “Kate Walking”—the proceeds, she says, will be donated to charity.

The art world has already heard from the most mercenary of artists—Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami declared they would be selling numerous NFTs of images of their works. Many other artists are sure to follow their example.

Christie’s, deeply in on the NFT Beeple hype, clearly wants to establish a category of NFT auctions capitalizing on the craze. Christie’s proudly announced that the sale of The First 5,000 Days would be made in crypto—specifically in Ethereum—the second largest cryptocurrency after Bitcoin, both of which have hit recent market highs. This was the first auction where Christie’s accepted crypto for payment, including the buyer’s premium.

The buyer of The First 5,000 Days, billionaire Vignesh Sundaresan, who calls himself Metakovan (described by the media as a cryptocurrency “whale”), is the founder of Metapurse, an equity fund for cryptocurrency. Paying in crypto for his auction purchase helped bring legitimacy to Ethereum and other such currencies.

Metakovan (does anyone use their real name in this “brave new world?”) plans to build a digital museum to display his collection of NFTs. He has also established a “public art project” known as B.20 (it contains certain Beeple NFTs Metakovan purchased in December, 2020 for $2.2 million) The Times reported that Metakovan has been selling millions of fractional shares (“tradeable virtual tokens”) in B.20—so he’s no fool.

Neither is Beeple. Shortly after the sale to Metakovan, it was reported that Beeple converted all of his Ethereum into millions in good old US greenbacks, as the saying goes: “Trust your mother but cut the cards.”

-

The Wende Museum

Valuing the ValuelessIn the midst of the Revolution of 1917, fiery Bolshevik Leon Trotsky warned members of the Menshevik party that their moderate methods in the revolutionary world would relegate them to history’s “dustbin.” In an ironic appropriation six decades later, Ronald Reagan declared that Marxism and Leninism were destined for the “ash heap” of history. These two historical figures were, of course, speaking metaphorically about what happens to outdated ideology; they weren’t necessarily referencing the physical junk that collects with time. But ideology isn’t far removed from the everyday stuff it creates, the things it leaves behind. It’s in the places where these things are disposed of, neglected and hidden away, that history rests most authentically. And if you make the hour drive from The Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley to The Wende Museum of The Cold War in Culver City, you can see that while The Gipper was correct about the end of 20th-century Marxist Leninism as he knew it, there’s a lot of inspirational potential in history’s dustbin waiting to upset rigid systems of belief that linger with us today.

Courtesy of the Wende Museum, photo by Daniel Dilanian. The seeds of The Wende Museum began in the 1990s, when its founder Justinian Jampol began scouring basements and flea markets in Eastern Europe, seeking Soviet-era relics, particularly from the German Democratic Republic (GDR), essentially rescuing material culture from landfills. As people east of the Iron Curtain prepared for an uncertain future, many were quick to dispose of the state-sanctioned art, party memorabilia, outdated appliances and recorded remembrances that made up their previous lives. Everyone had their own reasons for the purge. Most simply wanted to make room, supercharged by promises of freedom, democracy and worldwide commerce. For oligarchs-in-the-making, the documented past was potential kompromat, evidence of the socialist safety nets that free-market crony capitalism wouldn’t supply. As the shiny hope of a ration-free future dissolved into authoritarian kleptocracy in countries like Russia and Hungary, proofs of the not-too-distant past threatened to become resonant reminders of what state-sponsored repression could—and often would—come to look like in the 21st century.

Now The Wende Museum houses the most extensive collection of Soviet-era art and artifacts outside of Europe. With over 100,000 objects in its collection, this unique institution, whose name derives from a German term referring to the change that occurred up to and following the fall of the Berlin Wall, stands as an invaluable resource for historians around the world, and an innovative educational destination for younger visitors who only know a post–Cold War life. As an art venue, The Wende hosts rotating exhibitions from its collections and works made by artists inspired by its archive. It’s a uniquely confounding and informative place, empowered by contrasts and contradictions that would probably piss off Ronald Reagan and his Evil Empire label-making progeny.

Justinian Jampol. I met Jampol and Joes Segal, the Wende’s Chief Curator and Director of Programming for a private, socially-distanced, masked-up tour of the museum and its current exhibition, “Transformations: Living Room->Flea Market->Museum->Art,” which re-articulates the journey objects undertake as they enter the institution’s archives. It’s unlike any exhibit I’ve seen before: Guiding the visitor through the very process that makes the museum, the exhibition employs a vulnerable transparency and a self-criticality that has come to mark many of its public offerings.

Visitors start in a domestic space, a small apartment decorated with period wallpaper and framed artworks, a dining room table surrounded by sleek modern chairs with kangaroo-like legs, and various toys scattered about on the floor. As I peered through the suspended windows modeled on Cold War housing, I found myself thinking about the value attributed to mid-century modern design today, transmitted through the lens of tastemaker enterprises like Dwell Magazine and HGTV. While “form following function” reads more like a cliché sales pitch these days—a salve for conspicuous consumption—the Wende’s exhibit makes clear that many of the things on display look the way they do because they were designed to make the most of the materials and technologies available at the time. The chairs, for example, are plastic because other raw materials were in short supply.

Joes Segal. Staring at all these objects activated in me a desire for things made to last, and I was reminded of one their many online talks The Wende has hosted since the COVID pandemic, particularly one about Private Space during the Cold War. During the talk Prof. Susan E. Reid, historian of material culture and everyday life in the USSR, noted that after the ’50s, during a state-sponsored turn to modernized noncommunal apartment housing, there were debates about where people would put all the new consumer products that would furnish their living spaces, with, “some architects and designers arguing that people shouldn’t have cupboards because they just shouldn’t have all this stuff …to put away,” so as not to encourage “accumulating things just for the love of things.” As the Wende exhibition makes clear, there was no shortage of things or people willing to buy them.

From the exhibition’s Home section, visitors move to the Flea Market, a facsimile including folding tables filled with objects like radios, textiles and teddy bears, walls displaying flags and surveillance equipment, and a clothing rack lined with military uniforms. As we pause and flip through a fascinating scrapbook of photos, postcards and written memories made by a cooperative of workers, Jampol notes, “If we (The Wende) weren’t here, a lot of these things would have disappeared …it’s endangered material.”

Courtesy of the Wende Museum, photo by Daniel Dilanian. Jampol and Segal point out that the museum actively collects things perceived to have little to no market value; once a certain kind of Cold War collectible becomes popular, they tend to move on to pursuing something else. The two men, bouncing ideas and observations back and forth with ease, tell me they actually get disappointed when the monetary valuations of things in the collection rise because “insurance costs and security costs go up.” Segal notes that developing their collection as a search for unearthed historical value is like a “secret sauce” that enables the museum to grow in a way that might be impossible for other institutions. It’s quite an accomplishment how they model the value in valuing the valueless.

We then move into the exhibition’s Museum section, a simulacrum of museological space with Soviet realist paintings and sculptures of proud workers and model comrades accompanied by official-looking wall text, velvet ropes separating viewers from art, and even a fake colonnade attached to the wall. These particular formalized elements look conspicuously designed to make the viewer aware of how the things surrounding a work of art create auras of authority. It echoes The Wende’s 2016 exhibition, “Questionable History,” which discussed art and artifacts through conflicting didactic labels stating interpretive positions in opposition to one another. For example, a pink bust of Lenin could be both pro and anti-socialist, a spontaneous reaction to the falling Berlin Wall and/or a nostalgic joke made in the last decade or so. In the end, the viewer is left to live in the uncomfortable space of uncertain “truths.”

Courtesy of the Wende Museum, photo by Daniel Dilanian. From there, the exhibit transitions through a mix of scientific machines on loan from The Getty with the word “ART” placed hilariously on the wall above them. These instruments, which measure material characteristics like tensile strength, sit as transitional objects—devices used to authenticate and stabilize artifacts as they make the journey from personal to public, ephemeral use into historical preservation. But things don’t end there: The exhibition then gives way to a selection of freshly made contemporary art inspired by items in the collection, the implication being that things in the archive start new journeys as catalysts for creative production after they find a home in the museum’s vaults. The inspirational potential is clear, for example, in Ken Gonzales-Day’s large photo mural composed of a collage of statues of leaders like Lenin and Stalin, recontextualized to reflect contemporary debates about what to do with monuments to the Confederacy in America today.

Courtesy of the Wende Museum, photo by Daniel Dilanian. Warmed by a fire pit in the museum’s sculpture garden, next to what will soon be a new community center, Joes and Jampol indulge my obligatory questions about how the museum positions itself within America’s politically polarized climate. Joes notes that some people get upset that the museum doesn’t demonize the GDR enough, while others want the opposite: “Other museums have the problem of getting people to care; ours is that often people care too much.”

The museum responds to these demands to take sides with critical neutrality, which itself acts as a looking glass, a reflection of the biases—latent or not—in its visitors. It’s a tricky balancing act that deftly challenges dualistic thinking. “Complexity can scare people off,” Jampol admits. “But it’s a worthwhile endeavor.” Joes adds, “If someone says ‘I get it,’ we’ve lost. Our success is in the confusion.”

-

Moving Forward with Women’s Center for Creative Work

GRACE AND GRITTo incarnate is to become embodied in form, and form follows function. From the outset of the year 2020, leadership at the Women’s Center for Creative Work began the task of expanding its physical form because they had had the good fortune of having outgrown their existing space. Born out of a series of successful “site-specific feminist dinner parties” in the Los Angeles area, the wishes of the regular attendees of those dinners, and a $10,000 grant from SPArt, the WCCW put down roots in the Frogtown/Elysian Valley area in 2015 as a nonprofit. The function of this form: to foster an intentional, accessible community as publicly as possible. It’s fair to say that co-founders Kate Johnston, Sarah Williams and Katie Bachler (who is no longer with the organization) were extremely successful in doing so.

WCCW Family Dinner, July 2017, courtesy WCCW photo archive. One facet of this accessibility has manifested as a PDF you can download for free from the WCCW website called “A Feminist Organization’s Handbook.” The 75-page image–filled tome is a love letter to the work that they put into building their business: essays, flow charts, photos and documented processes available free and on demand for anyone in the world to download and peruse. By the act of compiling this handbook and giving the world a clear view into their mindsets as they began such a massive undertaking, they have made high-level business planning more accessible. Anyone with the will and courage can use their experiences outlined in the handbook as helpful guidelines to lay their own feminist business foundation without spending hundreds of dollars on coaches and consultants.

With this intentionality applied to their core values, WCCW’s audience and community growth was inevitable. Those core values are radically intersectional and inclusive, with the safety of women of color, trans women and disabled women given the highest priority. When put into practice, these values dictated the programming they hosted in the space: workshops, book clubs, performances and more. It’s part of what motivated the center’s new Communications & Marketing Director, Kamala Puligandla, to move to Los Angeles from the Bay Area three years ago. “I would come down to LA to visit and go to all the workshops at the Women’s Center,” she says in a video chat. “There’s this beautiful way where things collide at the Women’s Center and I’ve always been really invested in that.”

The new Highland Park space, 2021, courtesy WCCW photo archive. There’s so much more that can be said about the WCCW’s role in their community: partnerships with the local elementary school, partnerships with neighboring businesses, contributions to the local neighborhood council, the launch of their in-house publishing platform “Co-Conspirator Press.” Yet it was the uncertainties that came with the pandemic, coupled with leadership’s commitment to intentionality, that led co-founder Johnston to make the decision to reverse all plans of adding to their space, and move out of their beloved home of five years. (The very week they were to sign a new agreement with their landlord to expand into the warehouse next door, the state government began the mandated lockdown.) Consequently, the WCCW downsized: the staff packed up and moved out of their multi-room warehouse space in Frogtown and into a much smaller studio in Highland Park. Yet the ramifications of letting go of the former site have been startlingly positive. Resources that once went into maintaining physical space for a limited number of present bodies have been redirected to creating print and digital space that accommodates hundreds of eyeballs, remotely.

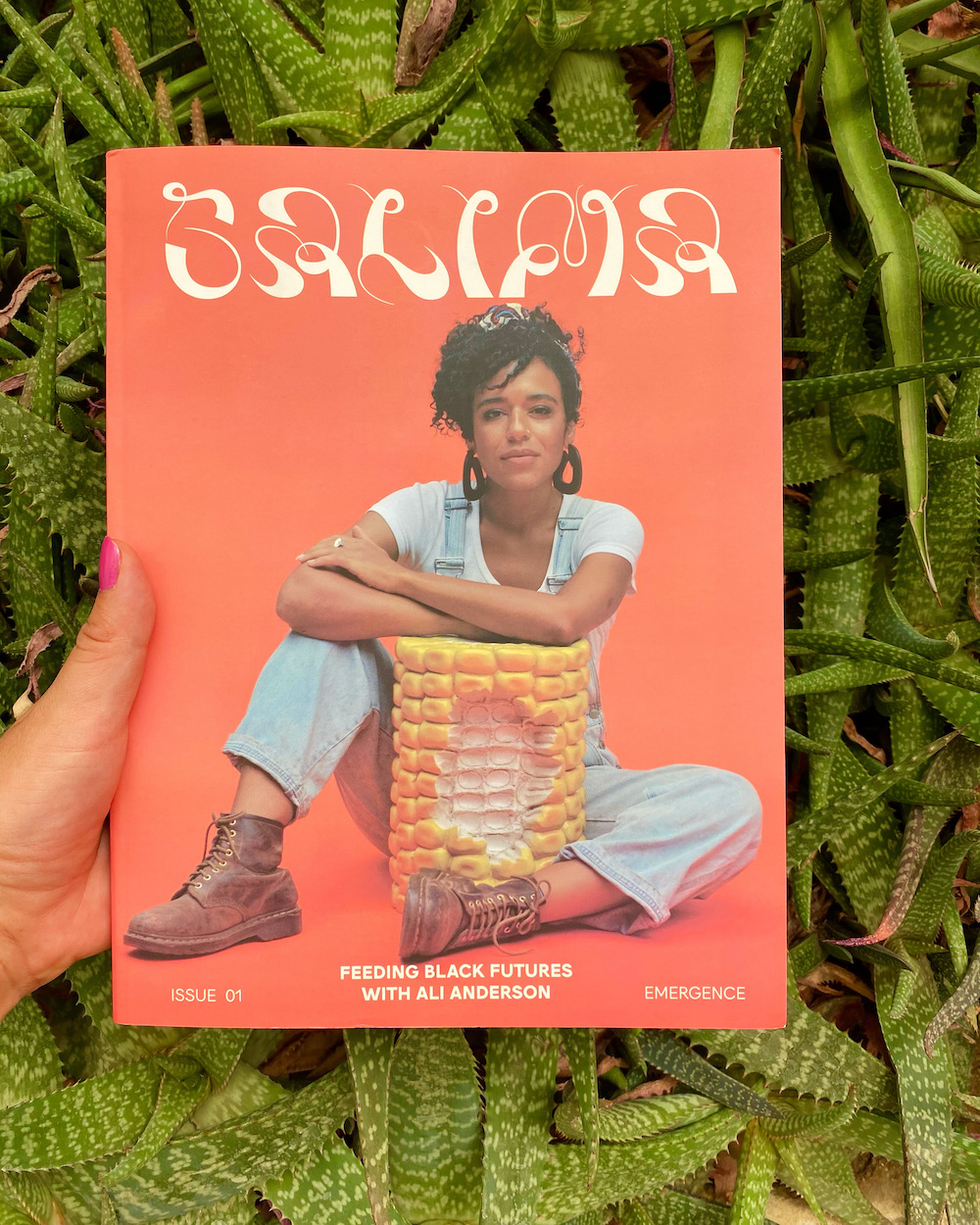

SALIMA Issue 1 cover, 2021. Thus, the Women’s Center for Creative Work has reincarnated: embodiment through online events has expanded its audience globally, and embodiment through SALIMA, a new print magazine just launched this year, keeps the community engaged in a material way. “It’s been a huge learning curve, but it’s been really fun and amazing,” Williams tells me. “There’s so many exciting people and voices and artists involved in all of these different ways. It feels like the [physical] space in a magazine, to me.” This is essentially a win-win for the Center and for people who—because of chronic illness, physical challenges or their location—were not always able to take advantage of the in-person programming available. This incarnation of the WCCW is the most accessible the organization has ever been.

Williams and her colleagues are working on making some of these programmatic changes permanent while tweaking others. The membership subscription they offer— which makes up 15% of their pre-pandemic income—is being restructured to reflect the changes the organization had to make last year. Responding positively to something as momentous and unexpected as a global pandemic while still serving a mission of creating, maintaining and sharing accessible feminist space takes both grace and grit, which the leadership and staff of the Women’s Center have ably demonstrated.

Editor’s Note: After publication of the article, the Women’s Center for Creative Work has since changed their name to Feminist Center for Creative Work

-

Secret Garden: David Horvitz

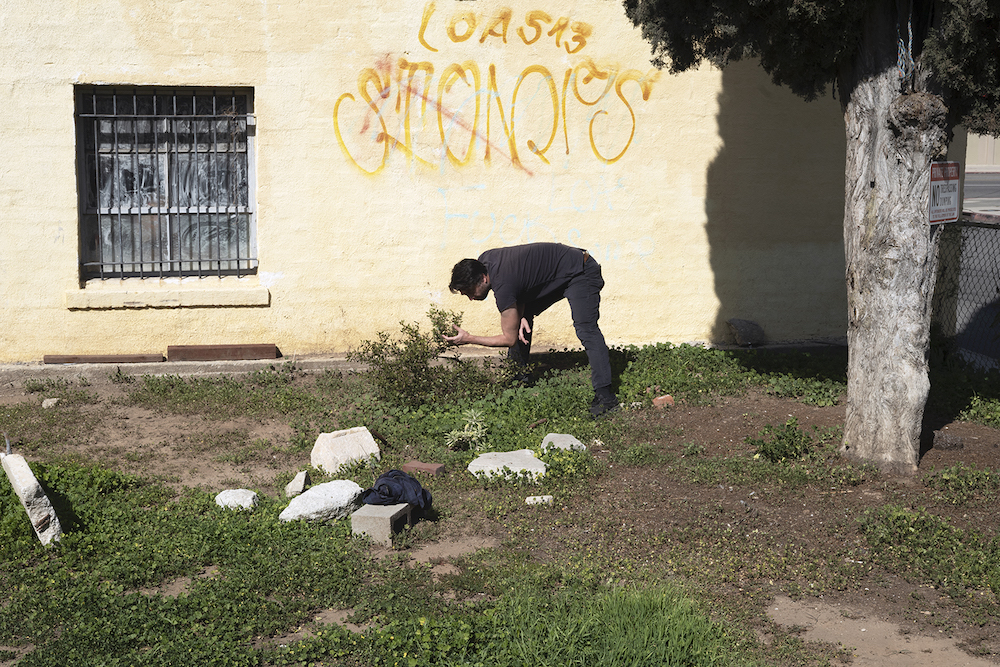

Exploring the Balance Between Private and PublicI met David Horvitz three years ago when he hand-delivered me an edamame plant he had been offering to his community via social media. Now, three years later, we meet again to conduct this interview in the garden he has been building. The garden in question is a previously vacant lot in Arlington Heights, a neighborhood in Central Los Angeles, near the Underground Museum and his studio. The lot, which became vacant after the house on the property burned down, is roughly 5,000 square feet and, prior to Horvitz’ interventions, was mostly dirt, grass and weeds. “I’m always finding buried knicknacks from the house when we dig. A lot of marbles,” Horvitz tells me.

Horvitz has worked with horticulture in several instances, though this is certainly his largest-scale and most ambitious plant-based work to date. The artist, age 39, who now lives and works in his native Los Angeles (after a stint in New York on graduating from Bard’s MFA program in 2010), first exhibited horticultural work when he planted seeds in a book that eventually grew into a tree. The seeds used were collected from Zuccotti Park during the Occupy Wall Street protests there. When making this work, Horvitz was “thinking about the trees as shelter and also as witness to this political moment that was happening in the background of the landscaping.” The tree was donated to, and currently resides at, Bard College, where it was planted in the ground and has since grown quite large. This notion of trees in the foreground, with bodies as subplot, persists throughout his oeuvre, culminating in his most recent work, his garden.

Early stages of David Horvitz’ garden. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol. When I arrive, the garden, which is still awaiting its concrete benches, is awash with midday sun. The space is entirely exposed, as much to the elements as to the street. The street, despite its proximity to bustling Washington Boulevard, is residential and fairly quiet. We walk through the garden while Horvitz gestures and tells me each tree or new bloom’s horticultural story—where they’re native to, where the seeds are from, and how they grow. He spots a new bloom—a tiny green leaf sprouting from the soil almost invisible to the untrained eye—and is visibly excited, placing a rock next to it to ensure “we (I know that in reality he means me but is too polite to say so) do not trample it.”

After obtaining permission from the lot’s landlord, Horvitz teamed up with architectural design firm TERREMOTO to transform the derelict space into a garden. When planting they talked about holding a designated space reserved for people but decided, instead, to allow the trees to dominate. In urban gardens, trees typically exist in the background, activated by the bodies that visit—thinking of his earlier project, they wanted to consider how it might feel for bodies to take a backseat while the trees hold centerstage. So far, they have planted over 100 trees. The garden’s concept required rocks so Horvitz and David Godshall, of TERREMOTO, reached out to LACMA Curator Christine Y. Kim to gather rubble from the museum’s demolition site. The result is a zen rock garden, a transplant of urban ruins from a renowned longstanding art space repurposed to another (much more transient) art space. If LACMA’s controversial and politicized demolition has been critiqued as a symbol of waste and excess, then Horvitz’ garden is the antithesis; a space lacking in financial incentive built up from the ruins of a domestic building and incorporating ruins from an institutional one.

Freshly cultivated garden by David Horvitz and David Godshall. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol. The Davids (Horvitz and Godshall) are unclear exactly how the location will be used. They may open it up to arts programming such as related talks, performance and happenings. Though it may just be a garden, open by appointment. He mentions its visibility to the public and that some neighbors have expressed wanting to have a BBQ or party there. While wanting the space to feel communal, there is simultaneously a need to preserve. The main rule is that it is a place for the plants, where the people are merely visitors. This tension of public vs. private continues to make itself known; the garden is visible from the street but behind a gate under lock and key. There have been several instances of graffiti which Horvitz is undecided on how to address. “I’m tempted to keep it,” he says. “Or incorporate it into a mural.”

Horvitz has long been considering the boundary between public and private. Since graduating from Bard in 2010, he has become quite known for his mail art and virtual artwork, drawing on the influence of conceptual artists before him like Bas Jan Ader and On Kawara. His early film “Rarely Seen Bas Jan Ader Film” (2009) was uploaded to YouTube under the premise that it was “found in Ader’s locker at UC Irvine after his disappearance at sea in 1975, and that the film was assumed unusable because it abruptly runs out just as the figure enters the water.” The few-second-long black-and-white film depicting a figure biking into the ocean was then made into an artist edition book, published by 2nd Cannon Publications. This blurring of fact and fiction, or history and mythology, discreetly inserts itself into the narrative—thus questioning the bounds of privacy by pushing them. I was first introduced to his practice with his 2007 work, I will think about you for one minute, where one can pay $1 and Horvitz will think about them for one minute, emailing them the time he starts thinking, and the time he stops. With this piece (still ongoing) he challenges the intimacy and visibility between artist and audience, momentarily collapsing the distance between the two. Particularly notable is the second email he sends once the minute is up: “I’ve stopped thinking about you.” Here, Horvitz draws a stark line between the public and private.

Horvitz tending to the garden. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol. Central to Horvitz’ work is the notion of access. Alongside many gallery and institutional exhibitions, including a group exhibition at the ICA Los Angeles this Spring, a solo at Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden in Germany earlier this year and exhibitions at Praz-Delavallade and Yvon Lambert in 2020, Horvitz extends his practice to inexpensive printed matter and free downloadable materials. His books are translated into 32 languages (so far), and his web content is downloadable via PDF, audio file or transcript from the website itself. He refutes the gate keeping oft associated with the arts and refers to his collectors less as “buying” his work, instead favoring the word funding. In one body of work, “Donations to Libraries” (2010), Horvitz donated archival boxes—one of which went to MoMA New York. The boxes, which appear as first-edition hardbound books but in reality contain a bottle of gin and a glass, were purchased by collectors who, in the acquisition contract, agree to buy a new bottle for the bookcases (which still live at the respective libraries) each year.

Horvitz addressed the public property conversation head-on in his two bodies of work: “Public Access” (2010–11) where he photographed himself on various California beaches and uploaded those images to the beach’s Wikipedia pages, and “Private Access,” where he did the same thing but on east coast beaches which are adversely privately owned. Exerting his public right both physically and digitally (in the case of the publicly gathered encyclopedia, Wikipedia) Horvitz explored the bounds between private and public access and the feeling of existence and visibility in both spaces. In a similarly terse video work made around the same time, A Walk at Dusk (2018), Horvitz walked through Trump’s Golf Club on the coast in Palos Verdes planting seeds from the Washingtonia robusta, a native Mexican fan palm. A gestural action in the face of the Trump presidency and his intended “wall,” Horvitz reclaims the land (which must, by California law, provide beach access to all 24/7) with native Mexican horticulture, collected from his grandmother’s garden.

Portrait of David Horvitz in his garden. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol. Horvitz, who has been working with galleries and institutions for the past two decades, has made a habit of pushing boundaries. For a Frieze New York Project in 2016, curated by Cecilia Alemani, he hired three professional pickpockets to attend the fair and stealthily distribute artworks to randomly selected fairgoers. At last year’s Frieze Los Angeles in Ruinart’s Champagne Room, he organized to gift glass artworks. The caveat being that in order to receive one you had to repeat the daily rotating password, which was shared without context by a mysterious gentlemen whose main role was to walk around the fair whispering the elected password into the ears of the public. Horvitz maintains that he does not eschew the traditional buy/sell market dynamic, rather he prefers to “make it a bit more difficult.”

Horvitz’ garden, as yet untitled, includes an artwork (or group exhibition, as he sometimes refers to it) which is collaborative in nature. Dirt Pile (2021-ongoing) is a cumulative pile of soil, so far featuring contributions from international artists. Morphing his own work with the contributions of other artists, Horvitz shirks direct ownership and invites other artists to inhabit his garden, via the soil from their homes. The garden—to which the landlord could at any moment extinguish David’s rights—is a practice in cultivating the ephemeral. Throughout this project, and over the course of his practice, Horvitz explores the balance between private and public, relishing the tensions between the two. Participating in both public and private spheres, Horvitz straddles both sides and revels in their inextricability.

-

A Conversation with Emily Barker

Make it NewEmily Barker (who uses they/them pronouns) is an artist and disability activist living in Los Angeles. They received their BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and have given talks at prestigious institutions including the Royal Academy of Art and UCLA. Barker adamantly refuses the low quality of life a disabled person is expected to endure and, although critical of the systems that measure a person’s value on their ability to produce, they are not without hope that things can and will change. Presently they are at-work designing and remodeling an accessible RV home that will be both affordable and stylish and a model for future dwellings. We spoke about constructing a meaningful life, the value of small-scale pleasures and friendship, and why radicalizing now seems the most logical thing in the world. They can be found on Instagram @celestial_investments.

Emily Barker, photo by Jass Leuo. JULIE SCHULTE: I wanted to talk to you about the most overused pandemic phrase: The New Normal. I’m thinking of how your incredible 2019 exhibition “Built to Scale” for Murmurs LA placed able-bodied viewers in a replica of your kitchen and created an experience of what it’s like to have everything inaccessible and out of reach. I’m curious if you see this Covid moment as an opportunity for a larger conversation of people rethinking what normal actually means?

EMILY BARKER: It’s a great question because it’s hilarious to me as someone who pre-COVID has been isolated in my house or a hospital for a total of two years of my life, stranded without transportation, and relying on people to give me rides; I am laughing because for me this is normal. In fact, my life has improved during COVID because I finally have transportation. Still, getting to my truck is a challenge because the sidewalks have electrical poles and lack curb cuts, so I have to ride down the middle of the street behind my apartment to get to my truck everyday because there is no accessible parking.

I will say that I do have various degrees of independence now due to surgeries I’ve had. My truck has a crane lift because I have the privilege of using that technology versus a ramp; I have the privilege of being able to drive when I’m not having a CRPS [Complex Regional Pain Syndrome] flare; I’m immuno-compromised so I was wearing nitro gloves and masks to parties and events long before this whole thing and people would look at me like I was crazy.

Emily Barker, At My Limit, 2019, photo by Josh Schaedel. Could you speak about disability narratives being misrepresented and misused under neoliberalism?

I think politics without class-consciousness is the neoliberal demise. When I became disabled 10 years ago these conversations weren’t happening. There wasn’t a “disability twitter.” There wasn’t a community you got to belong to and even now it’s splintered because we’re competing for scarce resources. And, the people in marginalized communities are the people with the most needs and their labor and work to survive is then appropriated because identity politics is something you can capitalize off of. My friends and I joke that we have a myriad of diagnoses that could make our whole lives all about bemoaning how fucked we are. For me, that’s never the point. It’s how to create and analyze systems so that we can all survive this, because my lived experience isn’t some diaristic thing that is personal to me. My lived experience is something millions of people are experiencing. It doesn’t ultimately matter that I have a heart condition, scoliosis, ocular degeneration, paraplegia, etc.—what matters is that since getting those I don’t get to have any quality of life within privatized healthcare.

But yeah, relying on other people: We do. It’s really messy and it’s really hard. So many people barely have the skills to care for themselves, so when you have someone with specific needs it creates tension. I have friends abused by parents because they need 24-hour care. They’re trolled for needing to pee too much! I experienced this abuse firsthand, and often it’s not even recognized as abuse. You know, being force-fed when I can’t stop vomiting because of all the cortisol dumped in my stomach. Ultimately, our society has normalized abuse to disabled people. Just the other day we had Disability Day of Remembrance where we honored those killed by caregivers. The people who are supposed to care for someone are the ones most likely to kill them—and still we live in a society where they should be grateful for what little care they get! Ableism is just so overwhelming that I want to focus instead on capitalism, because I know I can’t change people’s hearts. No matter how nice I am, I can’t make people give me dignity and empathy.

Emily Barker, Untitled (Grabber), 2019, photo by Josh Schaedel. Right, Marx speaks about there being no accounting for the health and well-being of the worker—just the ability to produce.

Yes, and Marx also said “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” But people can’t fathom the economic need. Friends of mine have monthly caregiving needs within the tens of thousands, and they soon find—even if they get settlements—a million dollars won’t take care of them for long. I am surprised more disabled people aren’t radicalized! To me, it’s common sense. Your only value is the labor you can produce with your body. We aren’t allowed to make money. I have to be in poverty to receive the care I need. I do all this work for free so I can educate people because my survival and others like me depends on it. It’s like planting seeds in a forest.

Emily Barker, Untitled (Austerity), 2019, photo by Josh Schaedel. It seems the shift to online shows is an afterthought/crisis response institutions benefit from for appearing accommodating. I don’t see this carrying into future design plans though. I read you’re presently designing accessible spaces. Could you tell me about where that’s headed?

The pre-concept for the Murmurs show was the 3D modeling my dear friend Tomasz Jan Groza and I were working on. We wanted to build a space that debunked the stereotype which accessible equals unaffordable. It’s a myth disabled people will lean into, but it’s totally wrong. What’s unaffordable is that for new building they don’t consult disabled people! We’re an afterthought. If we weren’t it wouldn’t be expensive. The majority of people in their lifetime—especially in America—will lose their mobility. And yet we’re living in this fog. This odd idea of reality that ignores the body, ignores gravity. That’s why I am building my own accessible RV. I’m hoping to have the RV finished by June, which is when the moratorium on evictions will be lifted, but crip time, just isn’t the same. It’s a long way to go and I have to rely on people laboring for me.

I don’t want to sound like a downer. I will say despite all of this I am happier now than I was before my accident. Before I was anxious and depressed, but now I see the things that frustrated me were out of my control and from the system itself. It’s something all of us are suffering under to varying degrees so all we can do is do our best to find ways to have a livable life and give our lives meaning. Buy all the teas. Own dogs. It may be small-scale but hey, you’re my friend and you want a Matcha latte with strawberry purée? You can have it. I’ve got that for you at my house.

-

Books: Jona Frank and John Divola

SoCal Photographers Cover It AllJona Frank’s new book, Cherry Hill, came out this spring almost simultaneously, but coincidentally, at the same time as another book, Terminus, by another SoCal photographer, John Divola. The coincidence is as fortunate as it is fortuitous because their subjects and approaches could not be more different. Even the geography in which they worked is far-flung, with Frank’s attention focused nearby on a Santa Monica lifestyle, while Divola’s ranges northeast to an abandoned military base in Victorville, CA. Though Divola’s is the more esoteric work, each photographer is at the top of his/her game.

In Frank’s Cherry Hill (above) the photographs are heartfelt but amusing. They could be straight out of a soap opera, if the episodes were soulful rather than facetious. What she has created is more of a sitcom. Movie actress Laura Dern plays a mom who is raising a daughter in a vintage Santa Monica home. We see the tussle between mother and daughter as the latter progresses from a bawling infant to an obstreperous 23 year old. Along the way, she assumes, naturally, that she’s much smarter, better, etc., than her mom. Dern sets the pace for the mutual frustration between mother and child as the daughter grows up.

from Terminus page 23, © John Divola John Divola’s Terminus is a book larger in format than Frank’s but with far fewer pages. All these photographs were, like the one above, made in abandoned houses on the closed George Air Force Base in Victorville. All were, Divola tells us, “exposed as b&w negatives in 2016.” Each looks down a narrow hallway toward a wall on which

Divola has spray-painted a black, sometimes mishappen circle. The deterioration that the hallways reveal is pitted against the indeterminant abstraction of the black circles. Little by little the camera advances down these halls until the image becomes just a vertical, black space—an inescapable end point. -

Decoder

Owning ArtSince the theme for this issue is “Private Property,” I assume someone besides me will be tackling non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and their sudden rise to collectibility—I’ll leave that to someone who can talk about them in some sort of intelligent, technical way and instead just talk about what NFTs are like.

Depending how you look at it, they either smoothly continue (or emphasize the absurdity) of a practice that has been normal for half a century: buying entirely conceptual art—in particular, buying works of conceptual art that could be reproduced by any reasonably functional adult being paid minimum wage.

I once heard a story on NPR about a middle-class collector who’d acquired an early Sol LeWitt for a few hundred dollars. The stunned host responded by saying he would kill (or was it die?) for that opportunity, which immediately begs the question: Why? Unless the plan is to sell it (in which case, why not just kill or die for the money it would bring instead?), you can have all there is to an early LeWitt wall drawing by googling “Sol LeWitt wall drawing,” picking your favorite set of 55-word instructions and pressing “print.” What did the host want exactly? Whatever it is, approximately the same thing is in an NFT.

Now, one aspect of this kind of acquisition is it can claim to be a species of philanthropy: you’re not only supporting the artist to the tune of X dollars, you are, for the sake of their future, supporting the idea that they should be getting X dollars every time they do what they’re doing. On the flipside there is some form of bragging right—just as the Carnegies and the Mellons can say “As in Carnegie Mellon?” you can say you’re the one who bought the thing, and there are allegedly circles where this improves the quality of the parties you get invited to.

These ways of owning have their uses, but not for me.

My favorite piece of mine that I still have around the house is a mug. I didn’t make the mug—I didn’t even design it. It took very little thinking, really, in the ordinary sense, to get this mug to be. Some friends in the art business called me up and wanted a picture to use for their kid’s bar mitzvah, and they were very precise: We want blue and green and balloons; there has to be a breakdancer and everyone has to be cheering them on, in a video arcade. Since I liked them and their kid and I was not a smouldering psychopathic egotist from the 1960s, I passed up the opportunity to send back a long and scathing letter saying that this bar mitzvah frippery was beneath me—a true artist—and they should’ve known it, and that I was therefore severing all commercial ties. I drew it, liked drawing it, and promptly forgot I drew it. A month later I got a package with a mug with the bar mitzvah picture on it.

A week or two after I put it on the shelf, a strange thing happened. I was drinking (as I so often do when in possession of a mug) and I looked down and realized this was a great mug. Really first-rate. Some excellent curatorial choices had been made: The outside, where my picture was printed, was white, like the paper, but the inside was that wonderful glossy dark blue you sometimes get in the tiles around the edge of swimming pools. It worked very well with all that blue and green I’d magic-markered on there. And the little figures standing on video game cabinets, forever at their party, and all so small and irregular (almost unreadable in industrial design terms—if you had proper Mickeys and Minnies on a mug, they’d be at least twice the size, parading properly around the cup). It was a nice, weird fun thing to drink from and I drank and I washed it, and forgot I had it, and a few days later remembered all over again.

Since then I’ve gone through dozens of cycles of not remembering the mug and then being ambushed by its existence all over again “Oh yeah, the bar mitzvah—look at all those happy little guys.” That, as far as I’m concerned, is how owning art should work.

-

Provenance: Senga Nengudi’s Public Rituals

Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978)What makes some spaces private and others public, if not rituals? In Los Angeles, a complex series of rituals reify our belief in private property. Property deeds, for instance, give physical form to a political notion; signing a deed a symbolic ritual that shapes spatial realities and delivers economic consequences. This is a ritual of exclusion, an agreement that this parcel of land is private and not public; it is mine and not yours.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young The pandemic greatly altered our daily rituals, sequestering homeowners to their private spaces, while those without a deed are left to live “private” lives in “public” spaces. Throughout modern history, few factors have had a greater impact on shaping urban landscapes than contagion. In 15th-century Italy, an epidemic led to the construction of leper islands; in newly industrialized 18th-century London, the outbreak of cholera resulted in modern sewage infrastructure. These upheavals remind us that urban spaces reflect rituals that are neither determined nor static. These spaces are daily experiments in collective living and continuously reconfigured by competing visions for the future, which contour the conditions and needs of the present.

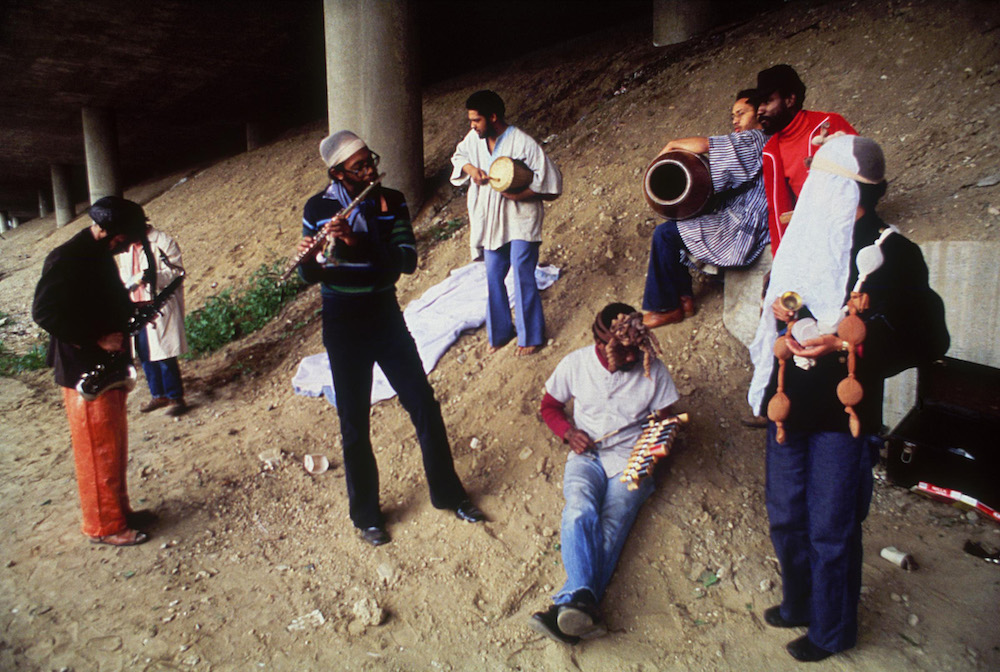

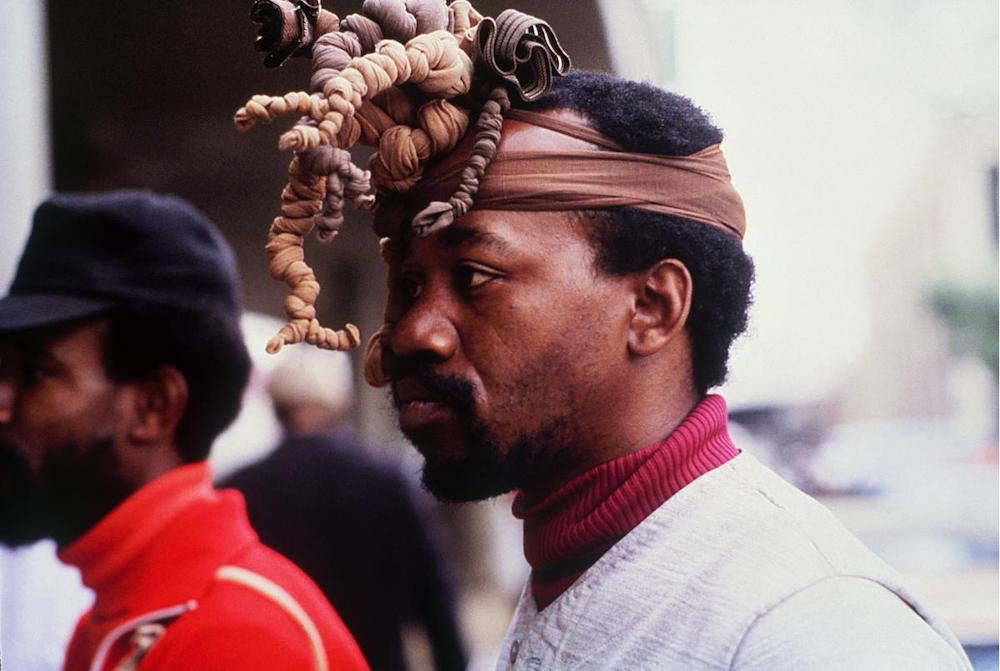

In her 1979 documentary Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes, Barbara McCullough interviews fellow LA artists of the 1970s Black Art movement (known as LA Rebellion) on the meaning of ritual in their work and practice. In the film, sculpture and performance artist Seng Nengudi describes her public performance work Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978) as a ritual that used public space as its medium.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young In the performance, Nengudi gathered several artists from the Studio Z Collective (1974–1980s) together under a freeway on Pico Boulevard. The participants carried instruments and small talismans and tokens, while adorned in head wraps, sheet scraps and other garments constructed by Nengudi from the nylon mesh of women’s tights. During the performance, artists David Hammons and Maren Hassinger danced and dueled to free-form jazz, acting out the tensions between “feminine” and “masculine” societal poles. Nengudi—draped in a large sheet—presided over them to perform an impassioned and improvised ritual of healing between them.

In a 2018 interview with Frieze magazine, Nengudi reflected on the performance’s freeway underpass locale, where “the energy of humans” was “already infused” by the unhoused people who had made it their home. A steep ledge beneath the freeway created a raised plateau where they had built encampments and left behind remnants of daily life. According to the artist, it was here, in a shadowy recess above LA’s privatized public space that people felt “protected,” and subsisted in an “almost ancient way of survival” akin to “Native American cliff dwellings.” Her performance sought to make these invisible rituals visible.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young Nengudi was exploring ritual as a means of transforming the mundane materials, bodily habits and forgotten land of everyday life into something sacred. Ritual can create a moment to acknowledge change and turmoil—but harness it towards collective healing, rather than strife. Today, when collective grieving, healing and recognition feel imperative and yet unattainable, Sengudi’s work reminds us to question the rituals that dictate urban space. Mass upheaval can open space to create new rituals, to choose how we change, and decide what is to remain sacred.

-

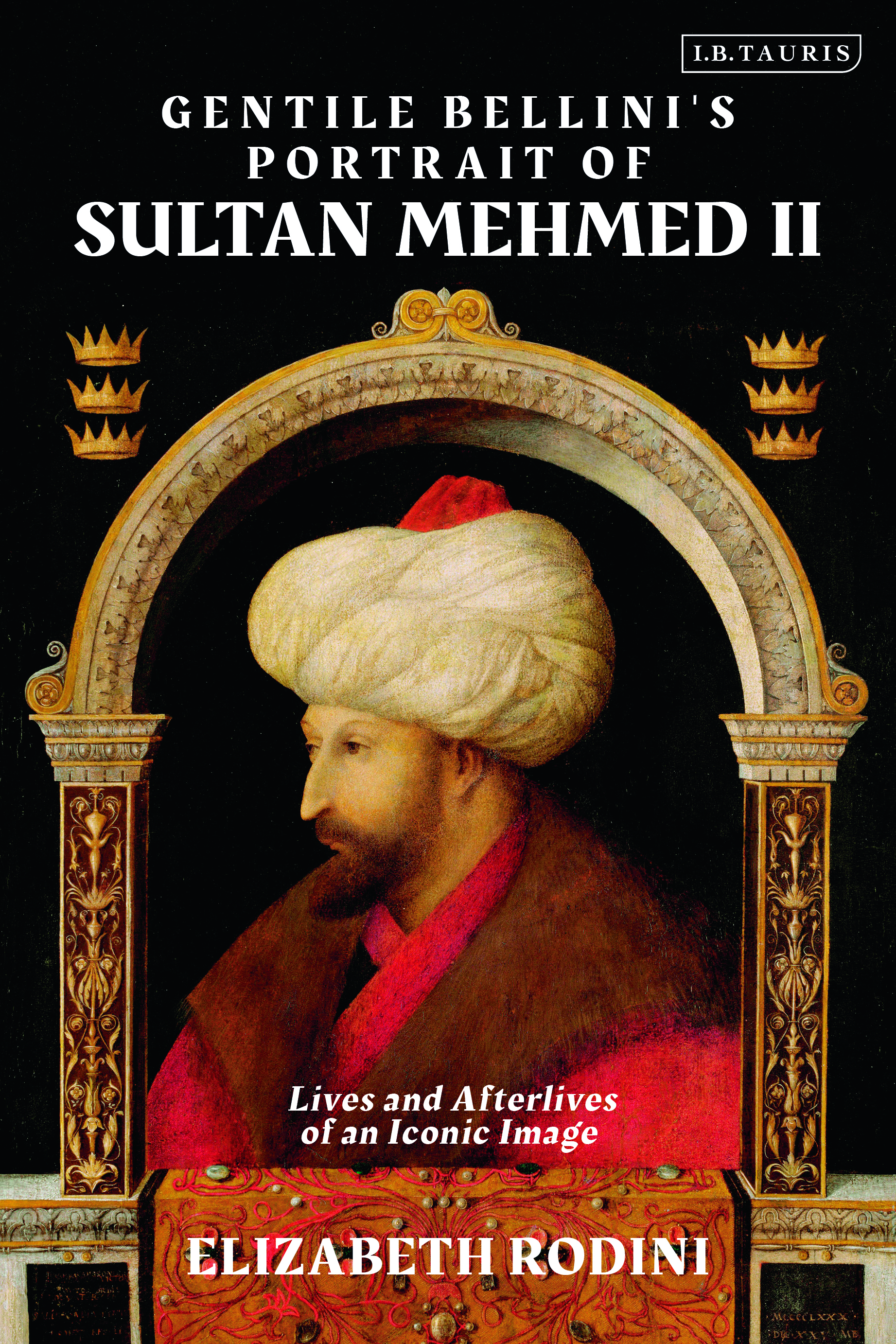

Book Review: Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II By Elizabeth Rodini

ABJECT OBJECTElizabeth Rodini’s Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II (2020) landed on my radar through meeting Rodini last year at the American Academy in Rome, where she is the Andrew Heiskell Arts Director. Rodini’s recent object biography investigates a number of intriguing and complex issues. Gentile Bellini, brother of the better-known Giovanni, was a Venetian artist. In 1479, he was commissioned to travel to Istanbul to paint a portrait of the Sultan, Mehmed II. This Renaissance portrait of an Ottoman sultan has gained a broad mystique, its legend perhaps eclipsing the actual substance of the canvas itself.

We may follow Rodini into the subterranean vaults of London’s National Gallery, where she finally encounters the portrait she has been exhaustively researching for so long …in a state of neglect, an object so altered and eroded as to bear little resemblance to its original state. This abject object had been the focus of intense strife and controversy, fought over for centuries.

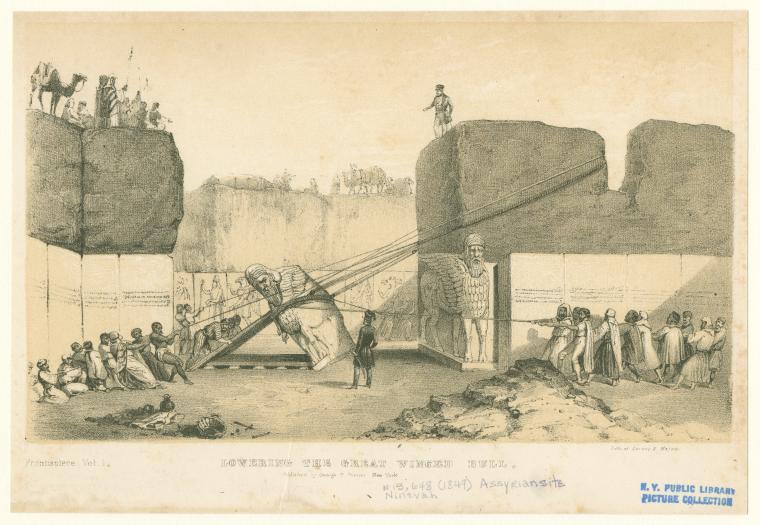

Lowering the Great Winged Bull, lithograph, frontispiece to Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, (London, 1849), The New Your Public Library, Digital Collections. Rodini brings this ostensibly dry and academic subject to life with the intensity of a gripping mystery novel…”Who done it?”

Cultural patrimony—the premise that artworks belong in the culture, often the country, where they were made—was a budding idea in 1912 when the owner of the painting, Enid, widow of collector and archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, passed away. The Layard collection, then housed in a palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal, was willed to her nephew, and London’s National Gallery. Before those parties could resolve who might have rights of ownership, they needed to get the painting to England—no small feat with Italy clinging to its treasured art objects.

This question of individual’s rights of ownership is a challenging one: Is it better to support the claims of individuals’ (or institutions) to private ownership of artwork, or will the broader good be served by placing the artwork in a setting deemed more culturally appropriate?

The Elgin/Parthenon Marbles are the “litmus test” for this issue, according to Rodini. Lord Elgin brought them from Greece to the British Museum in the early 19th century, where they have now resided for over 200 years. Greece, reasonably arguing that they were looted from the Parthenon in Athens, demands their return. The dispute has raged for centuries; Byron was among the first to condemn the looting. Once this is eventually settled, it may tip the scales for similar repatriation cases across the globe.

After James Fergusson, color lithograph, The Palaces of Nimroud Restored, color lithograph in Austen Henry Layard, The Monuments of Ninevah, 2nd Series (London, 1853), pl. 1. The New York Public Library, Digital Collections. Rodini takes a measured stance overall, weighing the value of the universality of priceless antiquities against the need to redress past injustices. Her description of studying an image in 2015 of an Assyrian winged bull in the British Museum, concurrent with reading news stories of ISIS defacing with power tools a nearly identical ancient sculpture in Iraq as part of a purge of imagistic artwork, definitely provides food for thought. Still, no excuses can be made for the colonialist and Orientalist impulses of these early plunderers, and repatriation will no doubt be one of the key challenges facing museums as they research the provenance of objects in their collections.

Rodini’s thoughtful work offers us an eye-opening window into many enticing, interwoven and labyrinthine realms.

Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II:

Lives and Afterlives of an Iconic ImageBy Elizabeth Rodini

224 pages

I.B. Tauris

-

Back in the U.S.S.R.

Bunker VisionIf you’re under 40 years old, it might be hard to understand the passion some boomers have about the evils of socialism. Scandinavia seems like a cool place to live. For all of its socialism, Cuba has a higher life expectancy than the United States, and even attracts medical tourists. So, how did the idea that socialism is awful gain such a foothold? The short answer is the Soviet Union and the Cold War. Before it collapsed 30 years ago, Ronald Reagan (who had released an LP about the socialist evils of Medicare) dubbed it “The Evil Empire.” Dear Comrades (2020) gives us a peek inside of this forbidden world.

The movie is set in 1962, and uses an actual event—the Novocherkassk massacre—as the jumping-off point, to explore a world where private property was taboo. The story hits the ground running (literally) as a woman is rushing to dress for the store “before everything sells out.” When she arrives at the crowded and meagerly supplied shop, she is whisked to the back. She is a party official and she gets special treatment. After the harried clerk provides everything on her extensive list, she rewards her with a pair of pantyhose, smuggled from the west. These are received with the enthusiasm that an inmate in prison might offer for a carton of cigarettes.

Her daughter doesn’t qualify for this special treatment, and joins a crowd that is protesting lowered wages, higher prices and shortages of goods. During this protest, shots are fired into the crowd, and the protest becomes a riot. Things get especially surreal when the authorities deny that the demonstration itself ever happened, much less the killings. When it proves to be impossible to remove the bloodstains from the pavement, a crew is brought in to lay a new layer of asphalt. When the party official’s daughter doesn’t return home, her mother assumes the worst. Much of what follows involves searching for unmarked graves with the mother’s boyfriend (a married KGB agent with a talent for getting them past checkpoints). Throughout all of this, Lyuda (the party official) keeps exclaiming that things have gone to Hell since Stalin died.

Using these perspectives, the film presents a dystopian overview of what existence in the Soviet Union was like for the people in all strata of life. The party official’s apartment is definitely nicer than a room in a subdivided house. The KGB agent’s apartment is noticeably nicer than hers. We get a tour of lives further down the food chain, as she searches for her daughter. This isn’t the genteel socialism of northern Europe. But this is what Boomers were taught that the word socialism means. If you’re planning to engage one in an argument about socialism, it’s probably good to understand that they’ll be focused on Soviet-era communism. And private property. It always come back to that.

-

ASK BABS

For Your Eyes OnlyDear Babs, My spouse stopped making art after getting her BFA in painting 10 years ago and hasn’t touched a brush to canvas in the five years we’ve been married, but the pandemic got her painting again, and I’ve never seen her happier. I know nothing about art, but I think hers is very cool. The problem is she refuses to show her work to anyone but me. How can I support her art and get it out into the world?

—Supportive in Scottsdale

Dear Supportive, If your spouse didn’t have an art-school background, I’d suggest you nudge her into the limelight as soon as possible. A little praise goes a long way when you’re new to calling yourself an “artist.” But your spouse is in a very different scenario. Even though she’s been on a long hiatus, she’s already an artist, and it’s going to take more than Etsy sales and kudos from the neighbors to get her to be comfortable showing her work again. You are not the person to tell her how to be an artist. She already is one.

The good news is she’s making art, you’re happy for her, AND you like her paintings. Consider yourself lucky that she trusts you enough to show you her work. Right now, your spouse needs the physical and mental space to grow and re-engage with the practice of making her art. Let her decide what that means. Only then will she be willing to show her work to other people. You have no idea how difficult it can be to emerge from creative hibernation.

Back in college, she had plenty of people to talk with about her art. For the time being, she has you, so get to know her work and her artistic inspirations. Ask her to make you a viewing/reading list so you can better understand the art that matters most to her. Get to know something about her materials, her techniques, why she paints what she paints. But remember, she doesn’t need a critic (and you’re not qualified to be one); she needs a comrade. Be her biggest fan. Trust that your informed enthusiasm will be infectious, and one day, your spouse will give you permission to spread the gospel about her work. Until then, be the support she needs and let her set the pace.

-

Poems

I Could Have Written That

By John Tottenham

Like you, I am tired

of my own voice,

these incessant I’s and me’s.

But what’s the alternative?

I don’t have the audacity

to employ another he or she

or We. Nothing could be worse,

psycholinguistically, than that sententious

and presumptuous first person plural,

which despite its unifying intentions,

seems to have an effect

that is entirely exclusionary.By William Minor

The Lovers

A man’s face may indicate

a tendency towards despair,

but it may also indicate a tendency

towards nothing in particular.

Sometimes a woman falls in love

with a man with this face.The Building

A mental hospital is just a building,

and a woman is just a person sitting in

a building.The Drawing

There are men who like to draw

and there are women who like to look

at wagons.The Journey

It is easy to imagine

a spiritual journey

lacking in grandeur.