I’m preoccupied lately with appearance and disappearance; the motions that simulate appearance and disappearance. It’s the sort of simulation that dates back to childhood for many of us—say, hide-and-seek for starters. I remember my brother and I trying to make crude magic with his Super-8 camera; playing, editing with the camera—turning him into a magician, an invisible man: here, there, nowhere; visible/invisible, trickster, magician. It can be a turning point moment (not sure whether it was for me at that moment); a simultaneous recognition of our vulnerability and our power—or at least our capacity for trickery. It’s the little dumb joke that we’re nevertheless in on.

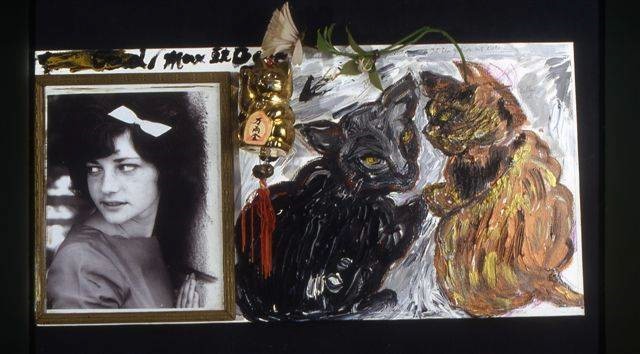

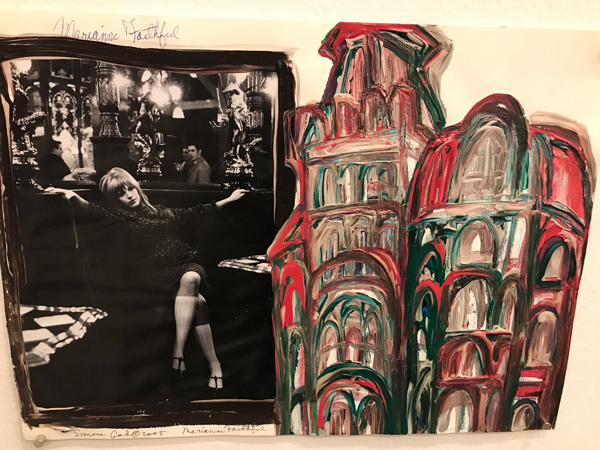

Simone was always acutely aware of the tenuousness, the fragility, the precarity of appearances, and certainly their physical embodiment. Without trying to attach a theoretical gloss to her life, I think she would agree that, especially in her later years, her work, whether as a fine artist or as an actor and Hollywood professional, was a constant re-assertion of her appearance, her presence in the world, her possession and hold on it. “I am here to show you something. Follow what I’m doing, see what I’ve done here. I’m saving a place for myself and it’s something to behold!” Every pigment-laden, hyper-expressive brush stroke of her paintings asserted her signature, her re-trace of a surface, a contour that recaptured a fleeting association or remembered sensation, the performance or recreation of a memory by her own hand.

I’m probably not alone in not having fully come to grips with her departure—for all the usual reasons we give in situations like these. ‘Not the way we blocked the scene.’ ‘Did someone jump their cue?’ ‘This was not in the contract.’ Funny how even in Hollywood, we can’t always control appearances and disappearances—these vexing interruptions to an imaginary, but no less unrelenting, production schedule. Yet notwithstanding the finality of certain disappearances, things, or certainly their shadows and echoes, do re-appear—in marks left behind, in after-effects, in re-enactment, in memory (our pre-electronic ‘special effects’). In the places they touched with their lives; and in the case of artists like Simone Gad, the places they possessed, that they marked and memorialized with their art. And we have the legacies they entrust to our care: their art, their documents—evidence of their life’s work, their souvenirs.

Souvenirs: I use that word deliberately, after reviewing the clips our mutual friend, Marsian De Lellis, edited from their gallery talk at the Track 16 Gallery. They’re really our souvenirs. I was always struck (not always favorably) by Simone’s enthusiasm for kitsch. We had discussed briefly the video of a little excursion Simone once made out into the desert, where she went through a shop of souvenirs, trinkets and similar gift items—all manifestly kitsch. Her energy and enthusiasm were palpable, and I confess it put a completely different spin on it. There’s a built-in bias for many of us who trade in a discourse built around standards of artistic or professional originality, excellence and integrity, or an artistic canon, to dismiss the hackneyed, garish second-hand imitations or clichéd simulacra of mass commercial producers as disposable gimcracks, gimmickery, kitsch and trash—notwithstanding our selective embrace of work that may incorporate or even swallow whole heaps of such stuff.

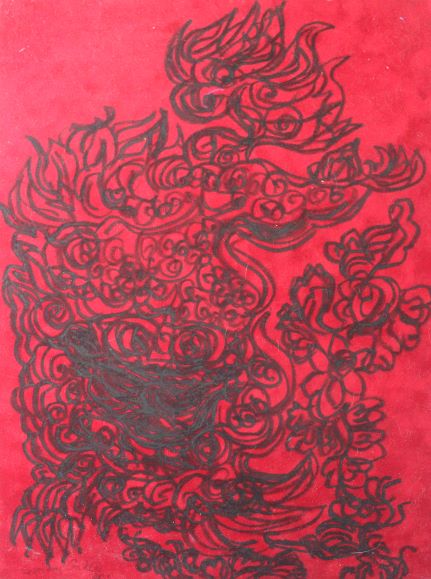

But there was something more going on there; and as I put it into perspective with her work—the pin-ups and rescue animals, the Fu dogs and pagodas, the porn shop peep show fragments and penny arcades—I suddenly understood her embrace and affection for these objects, which were not simply materials to be incorporated into assemblages or other constructions, or collaged into works on paper or canvas, but were in fact part of her subject—high-glossed and gussied-up, stockinged, corseted, hosed, harnessed, gilt, painted and varnished, primped and pimped, putting-their-bravest-face-on-a-bad-business, second-unit, third runner-up, Miss Congeniality, rejected and also-ran—rescued from the pound, 24-hour kill shelter, half-off counter, the throw-away bin, dive bar, motel lobby, coffee shop, dirty dungeon, in-sink-erator—little shop of delicious horrors—and offered a place in the pagoda, the shrine, the reliquary, the jewel box, the enchanted pavilion—guarded by Fu dogs and horned owls, protected and comforted by similarly rescued dogs, cats, bunnies.

Simone was never far from the edge of desperation. I’m not necessarily referring to her own psychological state. But she understood the blood-letting and bamboozlement behind the business of illusion-making and the infernal machinery constantly grinding it out and up right down to the earth’s scorched crust. Through her parents’ constant example and admonishments (but certainly not that alone), she was never unconscious of the razor’s edge divide between, as Primo Levi might put it, the drowned and the saved, or its absurd randomness. But like a spider pirouetting from a slender silk filament, she went right on brushing her dogs, embroidering her pin-ups, burnishing her pagodas. To rescue, redeem, savor and hold onto the moment in all its awkward, corny, rose-tinted, squirmy, sexy, intimidating, affectionate and delusional glow, might turn that desperation to an expression of simultaneous affirmation, affection, joy, mercy, and defiance.

0 Comments