What makes some spaces private and others public, if not rituals? In Los Angeles, a complex series of rituals reify our belief in private property. Property deeds, for instance, give physical form to a political notion; signing a deed a symbolic ritual that shapes spatial realities and delivers economic consequences. This is a ritual of exclusion, an agreement that this parcel of land is private and not public; it is mine and not yours.

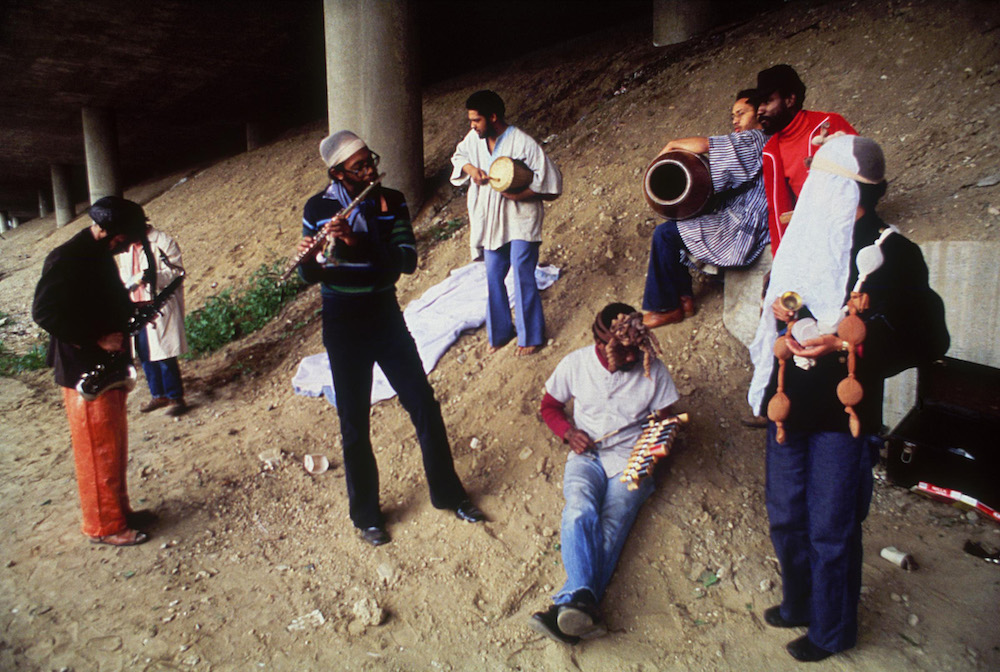

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young

The pandemic greatly altered our daily rituals, sequestering homeowners to their private spaces, while those without a deed are left to live “private” lives in “public” spaces. Throughout modern history, few factors have had a greater impact on shaping urban landscapes than contagion. In 15th-century Italy, an epidemic led to the construction of leper islands; in newly industrialized 18th-century London, the outbreak of cholera resulted in modern sewage infrastructure. These upheavals remind us that urban spaces reflect rituals that are neither determined nor static. These spaces are daily experiments in collective living and continuously reconfigured by competing visions for the future, which contour the conditions and needs of the present.

In her 1979 documentary Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes, Barbara McCullough interviews fellow LA artists of the 1970s Black Art movement (known as LA Rebellion) on the meaning of ritual in their work and practice. In the film, sculpture and performance artist Seng Nengudi describes her public performance work Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978) as a ritual that used public space as its medium.

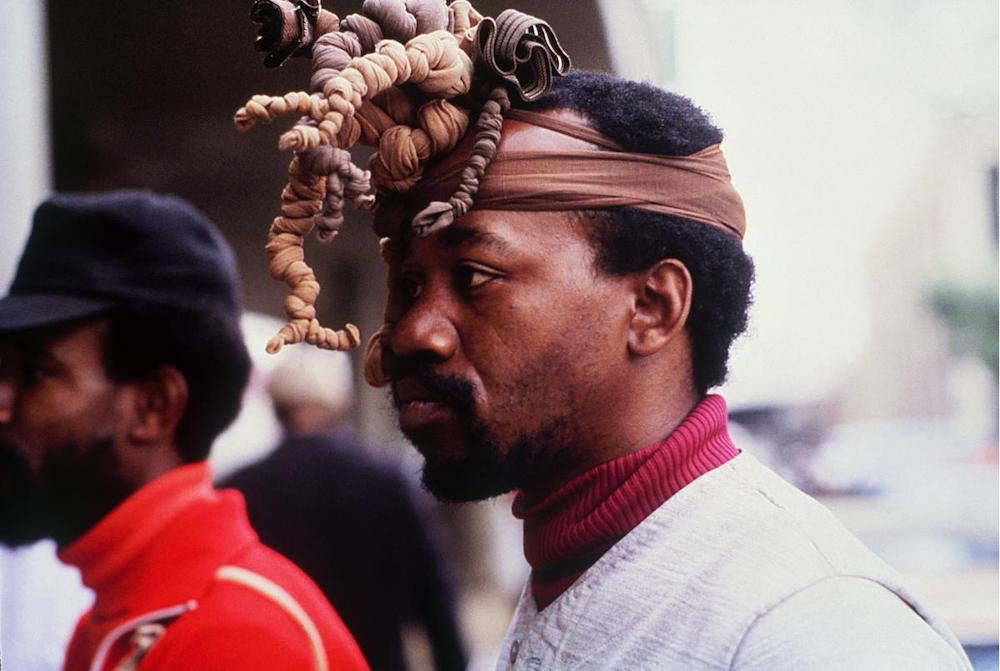

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young

In the performance, Nengudi gathered several artists from the Studio Z Collective (1974–1980s) together under a freeway on Pico Boulevard. The participants carried instruments and small talismans and tokens, while adorned in head wraps, sheet scraps and other garments constructed by Nengudi from the nylon mesh of women’s tights. During the performance, artists David Hammons and Maren Hassinger danced and dueled to free-form jazz, acting out the tensions between “feminine” and “masculine” societal poles. Nengudi—draped in a large sheet—presided over them to perform an impassioned and improvised ritual of healing between them.

In a 2018 interview with Frieze magazine, Nengudi reflected on the performance’s freeway underpass locale, where “the energy of humans” was “already infused” by the unhoused people who had made it their home. A steep ledge beneath the freeway created a raised plateau where they had built encampments and left behind remnants of daily life. According to the artist, it was here, in a shadowy recess above LA’s privatized public space that people felt “protected,” and subsisted in an “almost ancient way of survival” akin to “Native American cliff dwellings.” Her performance sought to make these invisible rituals visible.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young

Nengudi was exploring ritual as a means of transforming the mundane materials, bodily habits and forgotten land of everyday life into something sacred. Ritual can create a moment to acknowledge change and turmoil—but harness it towards collective healing, rather than strife. Today, when collective grieving, healing and recognition feel imperative and yet unattainable, Sengudi’s work reminds us to question the rituals that dictate urban space. Mass upheaval can open space to create new rituals, to choose how we change, and decide what is to remain sacred.