Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Kelly Rappleye

-

Provenance: ASCO’s Public Interventions in 1970s Los Angeles

Writing on the WallsThe artistic legacies of Mexican Muralism remain imprinted on LA’s urban landscape, in faded residues on cracked concrete structures and sometimes peeking out from peeling layers of whitewash anti-graffiti paint. Throughout the 1970s, many artists in Southern California’s Chicano Art Movement claimed the medium of the wall as public pulpit. These murals took up the pedagogical aims of Mexican Muralism to spread the good word of socialist revolution to the masses, educate the citizenry on radical histories, and challenge the doctrine of capitalist, colonial land privatization.

In the same period, a fluid art group called ASCO (from the Spanish phrase me da asco, loosely meaning “you make me sick” or synonymous with “nausea”) reconfigured this inherited lineage to provoke stereotypes of Chicano art. ASCO experimented with Dada and Fluxus practices of spatial détournement—making the familiar unfamiliar—to make live, ephemeral art from LA’s walls, streets and cultural materials. Rejecting what they perceived as a hegemonic collectivism in the prevalent “Mexican-American Art” motifs, ASCO preferred sarcasm and playful modes of repurposing to declarative ethical pronunciations, manifestos and social realism.

Still, ASCO was emphatically political, with co-founders Gronk (aka Glugio Nicandro), Harry Gamboa Jr, Willie Herrón III, and later joining member artist Patssi Valdez—all deeply involved in the fervent Chicano student activism across East LA high schools in the 1970s. Broadening their perspectives, they cultivated an internationalist engagement with aesthetic philosophies, accessed from a homegrown, punk vantage that was self-taught out of East LA barrio public schools, rather than elite art schools. Unlike the tinges of individualism and politics-as-consumer-cosplay often associated with the punk generation, ASCO’s nod to Fluxus experimented with practices of de-individuation to provoke concepts of normative identity. ASCO juxtaposed familiar spaces and symbols with modalities of popular culture—such as mail art and home videos—to reject the era’s commodification of identity and political aesthetics.

Harry Gamboa Jr.

Spray Paint LACMA, 1972

from the Asco era

©1972, Harry Gamboa Jr.ASCO’s playful reconfiguration of the mural form is evident in the striking group portrait Asshole Mural (1974). In it, the artists are dressed as archetypal Scarface-meets-American-Psycho 1970s assholes, with the men in three-piece ensembles while Patssi Valdez glares out at the camera from designer sunglasses. Assembled in an unyielding line across the frame, the group is poised coolly on either side of a gaping, black… hole that occupies the image’s central focus. The backdrop is an all-too familiar Los Angeles landscape; a lush, desert hillside with the cavernous excavation indicating a concrete aqueduct, linking to extractive water infrastructures of unfathomable industrial scale. This visual evocation alludes to the genocidal histories of Indigenous land dispossession and water theft that forged the way for LA’s urban development in the 20th century. The expansive networks of water extraction further imbricate the scene with ongoing labor struggles of Chicano farm workers across rural California against exploitative agricultural production.

Another of ASCO’s most famous live interventions was Spray Paint (1972), in which they responded to a racist statement by LACMA’s then-curator (who disregarded Chicano art as mere graffiti) by graffitiing their names on LACMA’s entrance, claiming the wall as their own ready-made. Though departing from more didactic methods of social realism found in traditional muralism, ASCO took up LA walls to explore themes of Chicano life, playing upon a rich tapestry of philosophical and historical influences through sardonic juxtaposition.

-

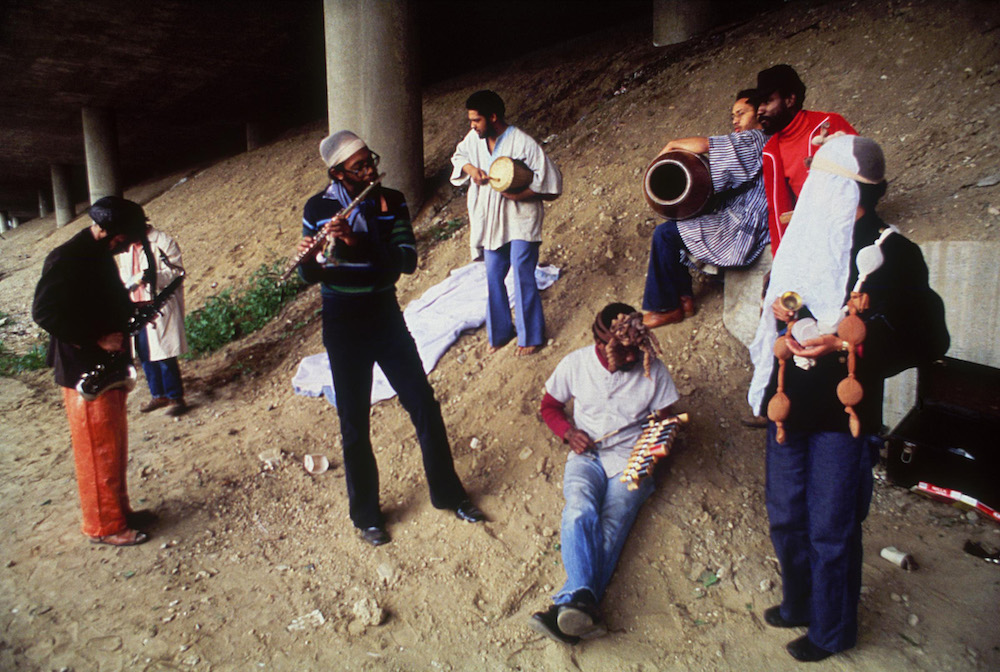

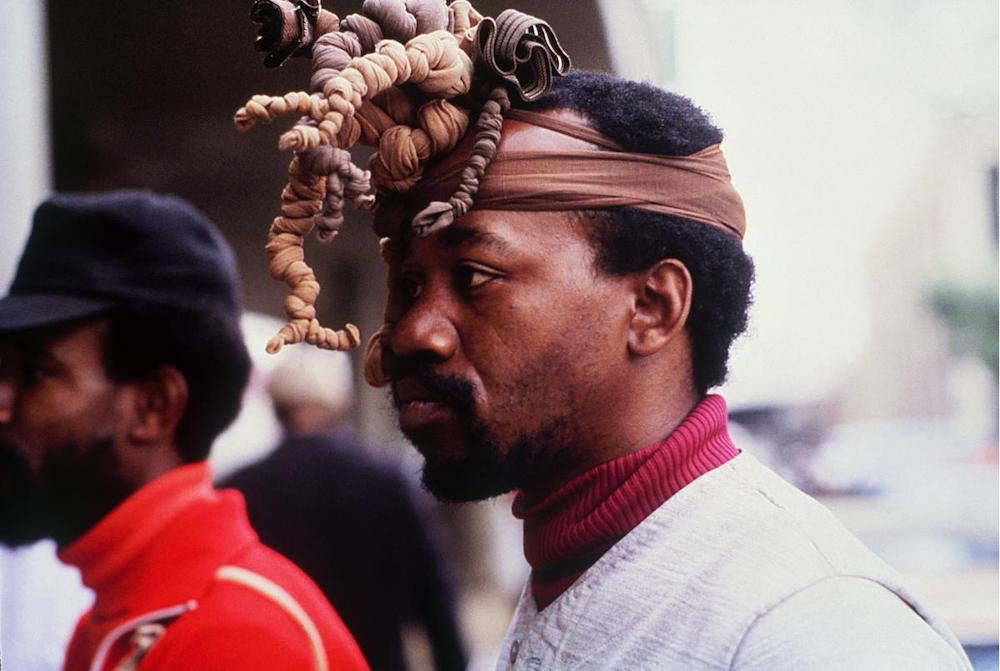

Provenance: Senga Nengudi’s Public Rituals

Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978)What makes some spaces private and others public, if not rituals? In Los Angeles, a complex series of rituals reify our belief in private property. Property deeds, for instance, give physical form to a political notion; signing a deed a symbolic ritual that shapes spatial realities and delivers economic consequences. This is a ritual of exclusion, an agreement that this parcel of land is private and not public; it is mine and not yours.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young The pandemic greatly altered our daily rituals, sequestering homeowners to their private spaces, while those without a deed are left to live “private” lives in “public” spaces. Throughout modern history, few factors have had a greater impact on shaping urban landscapes than contagion. In 15th-century Italy, an epidemic led to the construction of leper islands; in newly industrialized 18th-century London, the outbreak of cholera resulted in modern sewage infrastructure. These upheavals remind us that urban spaces reflect rituals that are neither determined nor static. These spaces are daily experiments in collective living and continuously reconfigured by competing visions for the future, which contour the conditions and needs of the present.

In her 1979 documentary Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes, Barbara McCullough interviews fellow LA artists of the 1970s Black Art movement (known as LA Rebellion) on the meaning of ritual in their work and practice. In the film, sculpture and performance artist Seng Nengudi describes her public performance work Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978) as a ritual that used public space as its medium.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young In the performance, Nengudi gathered several artists from the Studio Z Collective (1974–1980s) together under a freeway on Pico Boulevard. The participants carried instruments and small talismans and tokens, while adorned in head wraps, sheet scraps and other garments constructed by Nengudi from the nylon mesh of women’s tights. During the performance, artists David Hammons and Maren Hassinger danced and dueled to free-form jazz, acting out the tensions between “feminine” and “masculine” societal poles. Nengudi—draped in a large sheet—presided over them to perform an impassioned and improvised ritual of healing between them.

In a 2018 interview with Frieze magazine, Nengudi reflected on the performance’s freeway underpass locale, where “the energy of humans” was “already infused” by the unhoused people who had made it their home. A steep ledge beneath the freeway created a raised plateau where they had built encampments and left behind remnants of daily life. According to the artist, it was here, in a shadowy recess above LA’s privatized public space that people felt “protected,” and subsisted in an “almost ancient way of survival” akin to “Native American cliff dwellings.” Her performance sought to make these invisible rituals visible.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978. Chromogenic development print; series of 11, each: 12 × 18 in. © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Roderick ‘Quaku’ Young Nengudi was exploring ritual as a means of transforming the mundane materials, bodily habits and forgotten land of everyday life into something sacred. Ritual can create a moment to acknowledge change and turmoil—but harness it towards collective healing, rather than strife. Today, when collective grieving, healing and recognition feel imperative and yet unattainable, Sengudi’s work reminds us to question the rituals that dictate urban space. Mass upheaval can open space to create new rituals, to choose how we change, and decide what is to remain sacred.

-

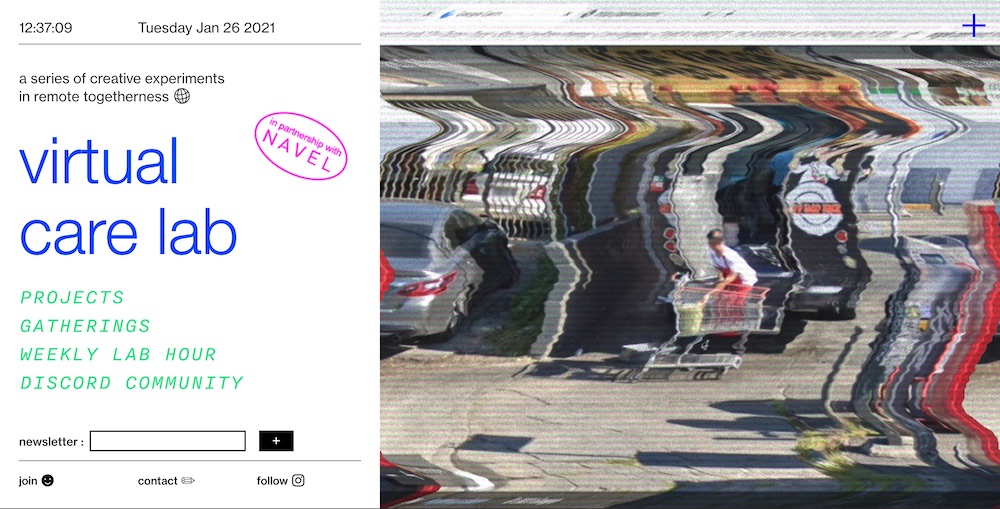

Virtual Care Lab Creates Remote Connection

Getting Together, ApartThe Virtual Care Lab (VCL), launched at the start of pandemic life, provides a digital community space for the wide-ranging interests of artists, disability activists and remote-togetherness enthusiasts to converge. Words like collectivity, togetherness, collaboration, participation and community abound across the VCL, which describes itself as “a series of creative experiments in remote togetherness” and offers a plethora of trans-disciplinary workshops that live up to this mantra.

The homespun, early-internet aesthetic of the VCL’s virtual home base invites experimentation, with bright colors, endearingly mismatched and haphazardly placed images that maintain a consistently welcoming vibe. VCL is created and run by two kaleidoscopic artists and cultural workers—filmmaker and sound artist Sara Suárez and digital arts virtuoso Alice Yuan Zhang—in partnership with NAVEL, the vibrant community arts space and nonprofit that has been developing a presence in DTLA since 2014.

‘Portals’ page highlighting on-going, participatory digital arts projects from the Virtual Care Lab. While COVID brought a sudden surge of digital alternatives across arts and cultural platforms, and long overdue attention to digital and expanded practice art, the VCL seems to have established a digital arts platform uniquely suited for longevity. VCL’s primary focus is cultivating inclusive publics and experimenting with non-commodified ways of getting together. Serial, processual community events and workshops, like the monthly Organizers Hour for local activists, provide a consistency and regularity that pushes against the fractal, alienating temporality of internet immediacy and the constant onslaught of “newness” and real-time engagement demanded by social media platforms.

Every Saturday (2 p.m. PST), Kenny Zhao takes VCL participants on “field trips” to explore and learn from community spaces on the internet, with guided discussion exploring what kind of social glue holds each together. Zhao describes these events as experiments in “collaborative ideation,” a concept delineated by author-activist Adrienne Maree Brown. Brown’s theoretical framework for activism is inspired by LA sci-fi icon Octavia Butler, and fights to reclaim creativity, imagination and radical dreams of futurity from the jaws of capitalism, colonialism and the cult of neoliberal individualism, through collective creative practice.

Virtual Care Lab Events page showcasing weekly digital fieldtrips led by Kenny Zhao, ‘Gatherings’ Calendar, and Discord chatroom. The VCL’s digital infrastructure is spread across a home website, a VCL Discord page, and a profusion of inventive, horizontal digital platforms—including withfriends.com, yourworldoftext.com, Twitch streaming service, theonline.town, padlet.com, and are.ne (visual notepad)—among an array of more familiar tools to facilitate modes of remote group collaboration and live participation. On the VCL homesite, the community can access an events Calendar of upcoming “Gatherings,” and a digital archive chronicling past VCL projects; a weekly “Lab Hour” invites community ideation and experimentation. A selection of hand-drawn talismans with flashing collaged imagery bids visitors to enter the VCL “Portal,” each object linking to a different ongoing digital, participatory arts project.

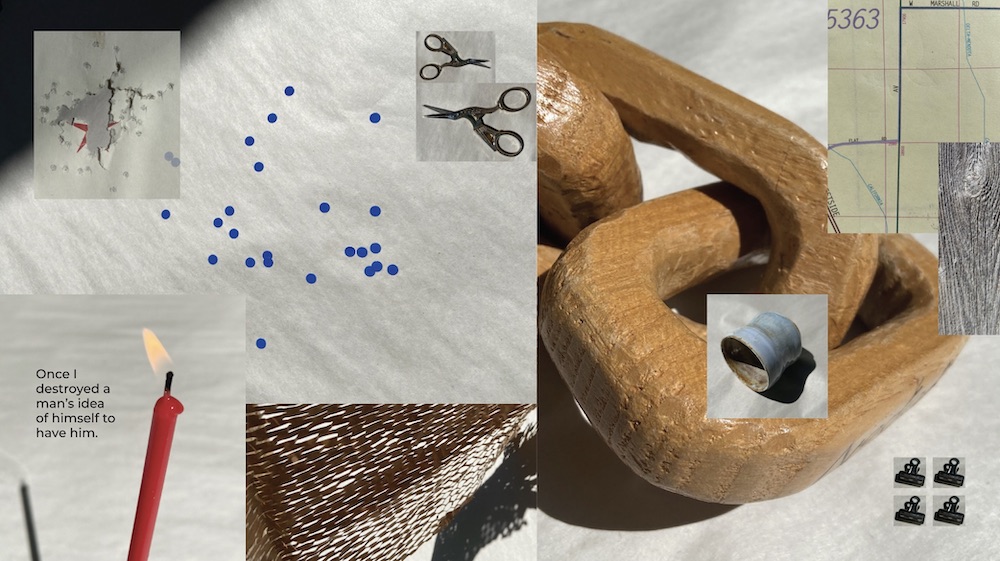

Poetry Soup, 2020. One project created by Kehkashan Khalid (username) is inspired by sci-fi writer and leftist darling Ursula Le Guin’s theory of flash fiction as a thought experiment. The Untold Edition— Collective Diary (2020–21) hosted on Padlet (collaborative digital notepad), displays a watercolor map of the world with sprinkled geotags marking doodles, short fiction musings and snapshots uploaded by contributors across the globe to produce a collective diary. Through another “Portal,” Poetry Soup (2020), a Frank O’Hara poem is accompanied by interactive audience prompts that invite users to create a visual poem in a collage-style webpage.

One highlight of the Lab, Sites of Passage (2020), is a digital video piece by artist Lucy Kerr that was produced in a Gathering, and includes an audience score for ongoing remote participation. The piece explores the themes of embodiment, disconnectivity and the alone-together nature of socializing-by-Zoom. In the hours-long long piece, the eerie voyeuristic eye of the Zoom lens is obscured by a distinct fogginess over the domestic settings, reminding us how similar each of these spaces becomes in the seriality of the Zoom box. Bodies move in and out of the frames performing the mundane daily tasks, while blurred faces read monotonous, matter-of-fact accounts of the rituals and routines that occupy the expansive banality of home-time in lockdown.

Lucy Kerr, Sites of Passage (still), 2020 Lingering questions run through the varied VCL projects—How can art practice provide a critical social realm to imagine creative modes of collectivity outside the auspices of commodification, borders and capital? Can digital communities dream of alternate futures to the apocalyptic one we seem to be careening towards?

The VCL invites submissions for community-led projects centered on “Care As Practice,” defined as an ongoing project that engages active participation through remote access. This concept of collective care traces to notions of radical care in Black feminism that posits a lived, habitual ethos of communal responsibility and the cultivation of collective nurturing practices as the antidote to neoliberal atomization and alienation. Scholar Maria Puig de la Bellacasa conceives of a “triptych of care—labor/ work, affect/affections, ethics/politics” in which care is the “concrete work of maintenance in interdependent worlds.” These dimensions are interwoven throughout VCL, where an insistence on the real presence of the disembodied other in digital space cultivates a digital practice of mutual care. This paradoxical tension of disembodied collectivity seems to be where the Virtual Care Lab situates itself most comfortably.

Website designed by Alice Yuan Zhang in Partnership with NAVEL LA, 2020.

-

Finding a Place (for art) in Skid Row

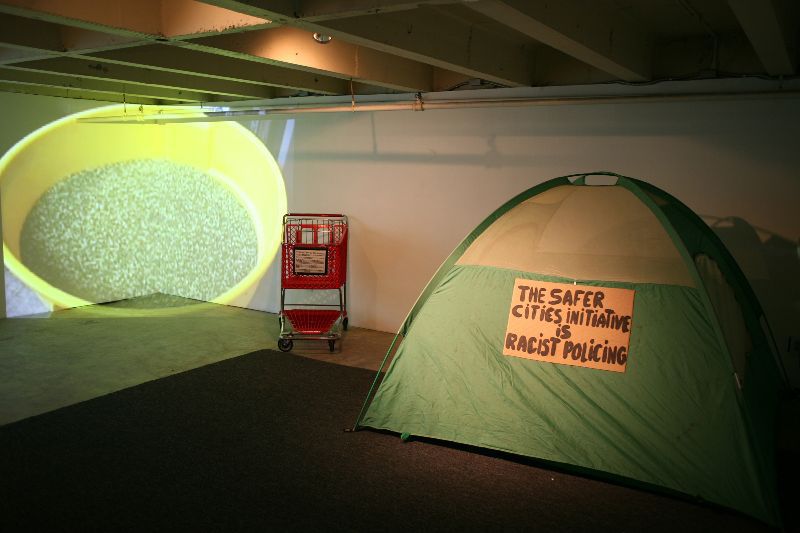

The LA Poverty Department and The Box GalleryThe Skid Row neighborhood of Downtown Los Angeles remains emblematic of the city’s ongoing epidemic of housing deprivation. More than 66,400 people were estimated to wake up each morning without stable housing in LA County as of LA Homeless Services Authority’s annual January count—even before the disastrous economic effects of COVID. While city officials call this recent wave a crisis, Angelenos are beginning to wonder if homelessness should be considered endemic to the core functioning of the city, rather than a recent anomaly. The glaring disparity in conditions of life for LA’s wealthy property owners and its impoverished, unhoused residents has been a recurring and increasing “crisis” since the 1980s. In fact, Skid Row has been a focal political flashpoint since the 1930s and remains the site of recurring experiments in urban planning. Yet, such attempts to target or contain city municipal services and social services have failed to provide the most essential need to the working class—housing.

Installation views: Los Angeles Poverty Department’s State of Incarceration, 2010, The Box, Los Angeles. (Images courtesy of The Box gallery e-mail newsletter) Bordering Skid Row is LA’s acclaimed Arts District, where a period of extreme gentrification ushered in upscale venues, thriving breweries, an influx of wealthy, loft-dwelling homeowners and skyrocketing rents, along with 12 leading commercial art galleries. The convergence of urban gentrification, art production, and LA’s “homeless crisis” in this area starkly illuminates the paradoxes of contemporary art, where radical artistic content is beset by the extractive gallery system. Cashing in on the cultural capital of the “art world” has been integral to developer and real-estate interests that have completely transformed Downtown LA, and brought immense pressure and heightened policing to Skid Row’s unhoused residents.

I spoke with an Arts’ District mainstay, The Box gallery, and a Skid Row performing arts organization, the Los Angeles Poverty Department (also known by its cheeky acronym LAPD), to understand how an art space can bring its unhoused neighbors into the gallery space, physically and virtually.

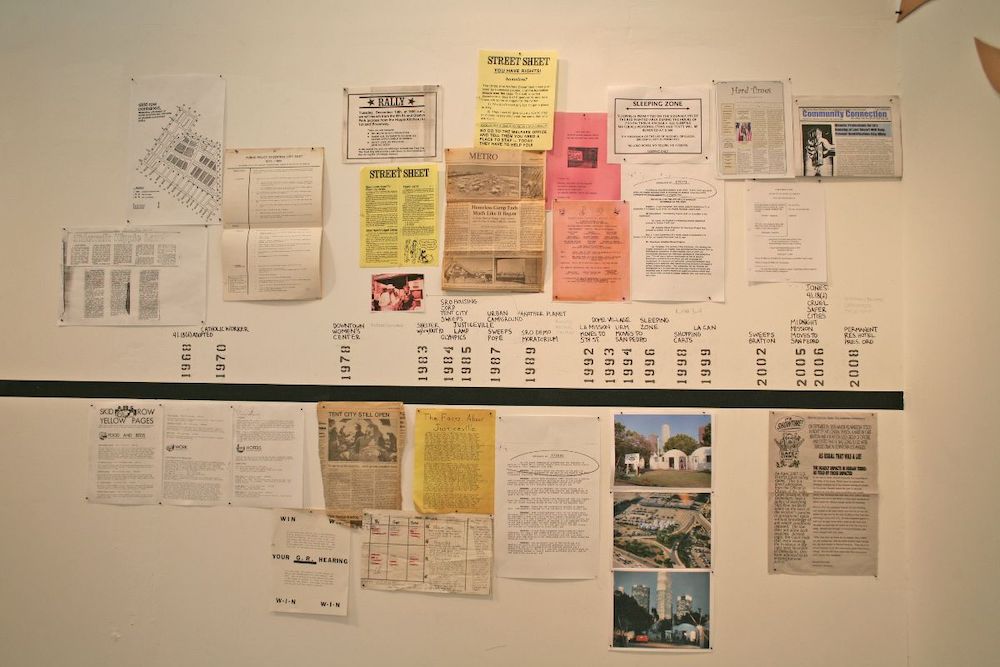

Installation Images: Skid Row History Museum at The Box, 2008. Images courtesy of LA Poverty Department. (Images courtesy of The Box gallery e-mail newsletter) Since 1986, LAPD has amplified the voices of Skid Row residents through performances and public art projects that form a counternarrative to the handwringing tragedy-porn espoused by liberals and right-wingers alike about Skid Row and its inhabitants. LAPD’s founder John Malpede was one of the first performance artists to work primarily with homeless actors, writers and participants. The mission is simple, yet profound: to share the concerns, needs, dreams and stories of Skid Row community members, in their own words.

The supportive and experimental relationship between LA Poverty Department and The Box’s founder and curator Mara McCarthy began in 2008 with the “Skid Row History Museum” exhibition at The Box’s former Chinatown location a few miles north of Skid Row, which hosted a flurry of participatory events, performances and musical acts, alongside an exhibition of archival material on Skid Row’s largely untold community history.

Installation Images: Skid Row History Museum at The Box, 2008. Images courtesy of LA Poverty Department. (Images courtesy of The Box gallery e-mail newsletter) LAPD’s Associate Director Henriette Brouwers fondly remembered the lively crowds when Skid Row came to The Box, with people hanging out of the windows for live performances, and crowds from all walks of life sharing a recognition of Skid Row beyond the dire conditions of American poverty. This vibrant exhibition demonstrated to Brouwers and Malpede the importance of having a physical art space to gather and exchange knowledge and care within the community, for the community.

They went on to create this space in 2015, opening the Skid Row History Museum & Archive, now located at 250 South Broadway. The space hosts performances, exhibitions and the Skid Row History archives, along with numerous ongoing community-led artistic and archival projects.

Installation Images: Skid Row History Museum at The Box, 2008. Images courtesy of LA Poverty Department. (Images courtesy of The Box gallery e-mail newsletter) Over LA’s lockdown summer of 2020, McCarthy saw an opportunity to highlight her gallery’s history with the LA Poverty Department through a digital campaign for gallery audiences stuck at home. The Box’s email newsletter series shared images and material from the 2010 “State of Incarceration” exhibition and performance series with LAPD that focused on the urgent issue of California’s prison overcrowding. The exhibition filled The Box with large, steel prison beds (paid for by the CBS soap opera, The Bold and the Beautiful in a quintessentially LA moment), where LAPD actors sat and rehearsed scripts developed from their lived experiences in prison. Brouwers recalled the unique interchange that occurred when gallery attendees, unlike the usual theater patrons, observed quietly and patiently. This allowed for a generative silence to develop as they occupied the prison beds together, mimicking the long silences and boredom of life on the “inside”, in a profound moment of non-theatrical performance.

Los Angeles Poverty Department, Walk the Talk parade/performance. Top image photographer: Austin Hines. Bottom image photographer: KCRW’s Avishay Artsy, 2012. Images courtesy of LA Poverty Department. (Images courtesy of The Box gallery e-mail newsletter) The exploratory projects between The Box gallery and LAPD provide a poignant example of how art spaces can create meaning with their communities. McCarthy reflected on her motivations to defy the social enclosures of the commercial art world by opening her space as a resource to LAPD, in the simple acknowledgment that the Arts District and Skid Row are part of the same Downtown community and need to learn how to act accordingly, and respect each other as neighbors.

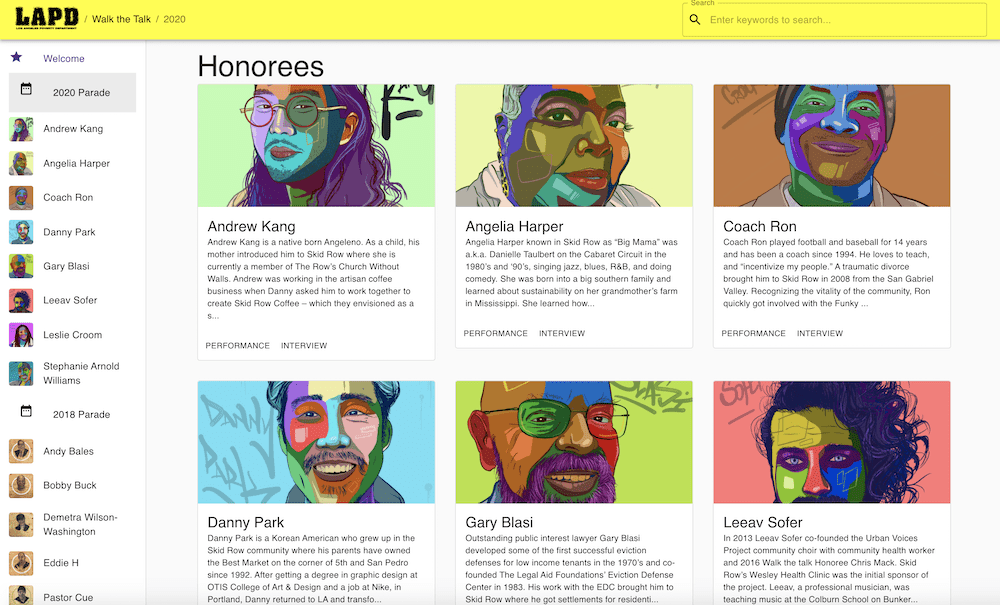

Screenshot of LAPoverty Department website, Walk the Talk digital archive. Website created by artist / technologist Rob Ochshorn. Permission granted from The Box gallery. (Images courtesy of The Box gallery e-mail newsletter) Throughout June and July, @theboxla celebrated the LAPD’s newly digitized “Walk the Talk” Archive, with short video excerpts from the archive’s nearly 70 hours of interviews with local heroes, activists and important figures who lived, worked and sometimes experienced homelessness in the Skid Row community since the 1980s. LAPD’s “Walk the Talk” began in 2008 with plans to create a Skid Row Walk of Fame to publicly hail unsung community leaders of Skid Row, complete with sidewalk plaque-stars mirroring the Hollywood Walk of Fame. They gathered the life stories of chosen local icons from transcribed interviews, which later provided scripts for a series of public performances. Years of bureaucratic barriers evolved the sidewalk project into a bi-annual “Walk the Talk” neighborhood march, inaugurated in 2012 with three days of boisterous marchers filling the streets of Downtown and Skid Row, performing these narratives. The digitization of this archive was finally completed this year by software designer Rob Ochshorn, providing an invaluable resource for a people’s history of Skid Row. The archival interviews capture the ingenuity, grit, and unfathomable strength of daily survival on the streets of Los Angeles, along with the truly affecting grace and wisdom of its dwellers.

The “Walk the Talk” digital archive interview series can be found on the LAPD website (lapovertydept.org) and @LApovertydepartment, and video highlights remain on The Box gallery’s Instagram, @theboxla.

-

PROVENANCE

Myth & Mural on Olvera StreetTucked between two of the quaint brick and wooden structures comprising the colonial phantasmagoria that is LA’s Olvera Street, is a rooftop mural painted by the famed Mexican activist, Marxist organizer and painter, David Alfaro Siqueiros. The passion project of 1920s preservationist Christine Sterling, Olvera Street represented Southern California’s new, much whiter population’s fantastical vision of “Mexican History.” Known today as the “original gentrifier,” Sterling partnered with the notorious Los Angeles Times editor and real-estate mogul Harry Chandler to help construct this vision at the center of downtown. With Chandler’s financial backing, Sterling revamped the street beside the Avila Adobe—a vestige from the Mission era of Spanish colonization—to create a simulacrum of a Mexican marketplace. Unencumbered by the long history of Spanish and Anglo colonization and genocide that had displaced so many indigenous Califorinian peoples, today’s Olvera Street remains true to Sterling and Chandler’s 1930s vision; a romanticized historical proxy that protects its visitors from acknowledging America’s genocidal past.

Soon after Olvera Street’s opening in 1930, Siquieros was commissioned to help complete Sterling’s spurious vision. Despite Siquieros’ renown as a leader of a political and cultural revolution in Mexico, founded in a rejection of U.S. Imperialism, the financial interests looking to trade in on Siqueiros’ notoriety and cultural capital were shocked and dismayed when he unveiled his completed mural, América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos (Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism, 1932). A striking homage to the indigenous culture and labor upon which the affluence and power of the emerging 20th-century Los Angeles metropolis was built, Siqueiros’ painting stands in stark contrast to its idyllic surround.

Olvera Street during COVID-19 pandemic, 2020. The mural depicts thick, nodular tree roots in brassy, oak-hued tendrils that dominate the pictorial frame in a rhizomatic field, enwrapping the viewer into its narrative of indigenous exploitation. The roots serve as a curvaceous canopy against which a sturdy Aztec pyramid is juxtaposed. The figure of an indigenous man is offered up in the center of the frame. The man is tightly bound to a wooden doublecross, his head hanging askew in tragic lifelessness. Perched atop the man, a vivid, yellow-golden eagle is perched with wings spread and beak agape, as if crying out in victorious joy; lording over its bounty of prey.

Though today the once vibrant mural has faded, this was part of Siqueiros’ original intent. Siqueiros insisted the mural never be repainted or restored to its original colorful state. According to him: the mural’s eventual decay reflects its boundedness to its environmental milieu, and to time as history. Unfortunately, the mural was never given the chance to age naturally as it was swiftly censored and painted over in 1932. Since that time, renewed attention brought about by Chicano civil rights activists working in the 1960s and 1970s inaugurated a restoration project. In a collaboration with the Getty Conservation Institute and “The City” (El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument), the mural restoration was finally completed in 2012 and can be seen for free at the American Tropical Interpretive Center located at the heart of Olvera Street.

Looking at the mural today, amidst ongoing ICE raids and mass detention, we must ask ourselves: What does Los Angeles seek to gain when it invests in the cultural capital of revolutionaries? More importantly, what does the city stand to lose in processes of urban regeneration built on historical myth making of a romanticized colonial past?

Perhaps we can look to Siqueiros’ work for the answer.

-

Stories About Impossible Decisions

Last Thursday night I braved the fiercely blustering wind and joined the trickle of funky-fresh San Francisco locals snaking through the industrial Dogpatch neighborhood, to land at Minnesota Street Project (MSP), a set of warehouses tucked under the 280 Freeway which houses galleries, artists studios and event spaces maintaining a stronghold on the SF gallery and contemporary art scene. Amidst the cold, industrial exterior the warm glow of a murmuring crowd gathered to sip beer and peruse the smaller galleries lining the cavernous warehouse space within the 1275 Minnesota Street gallery of MSP—while claiming spots on the fast-filling bleacher seating.

Hosts Ellison Libiran and Mcardle Hankin The event’s hosts—story-producers and longtime friends Ellison Libiran and Mcardle Hankin—took the stage and shared a casual, kinetic vibe as they passed playful, sardonic banter and read out selections from audience-submitted responses to the night’s theme—“Don’t Just Stand There—Stories About Impossible Decisions.” The duo charmingly recalled the origin story of BackPocket , and how the curated live storytelling event series emerged from their co-hosted local radio show on Bff.fm, and seeks to bring friends and strangers alike to share and connect in the absurd, dark and humorous stories of our lives. The event delivered with stories sharing unexpected takes and poignant, personal dramas far outside the realm of cliche.

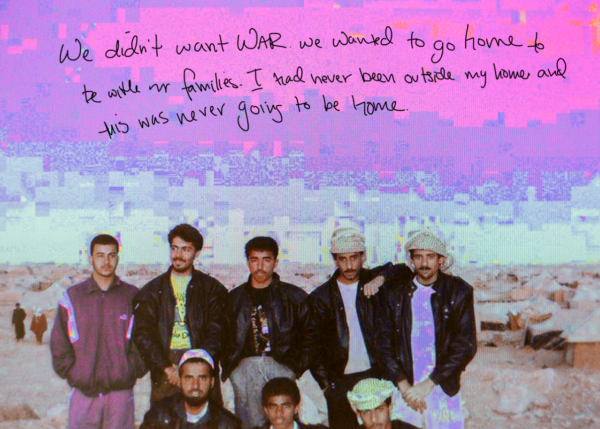

Wesaam Al-Badry’s slideshow One highlight came from Iraqi-born visual and mixed-media artist, Wesaam Al-Badry, whose multimedia video piece, It Smelled Like Sweet Green Apples, led the audience through a series of images of grainy, ’90s disposable camera images overlaid with thick, colorful graphic doodles in the artist’s signature hand. In it, Al-Badry narrates the story of his childhood growing up in a refugee camp as one of thousands of Iraqi citizens displaced after the Iraqi uprisings of the early 1990s, serving a powerful reminder to the viewer of the resilience and adaptability of children, even to the most inhumane conditions. Another tender story from April Dembosky, health reporter for KQED, hauntingly incorporated the use of audio recordings to share an intimate encounter with the darkest possibilities of untreated mental illness and left the crowd with deep, moral ambiguities to chew on.

Jeff Greenwald Perhaps the most triumphant story of the night, bringing audible gasps from the crowd, came from esteemed Oakland-based journalist and nonfiction author Jeff Greenwald who told a wild, twisting tale of a beloved hippie cousin who disappeared—only to reappear married and on the lam from the law with one of the FBI’s Most Wanted. We hung around after the show, sharing reflections and trying to grab one last beer before the MSP staff had to politely kick us out.

A Thursday evening buzzing with multimedia arts, humor and a community hankering to embrace the true diversity of experiences and stories of our community left us feeling we had stumbled upon one of SF’s hidden wonders.

For more info on BackPocket: www.backpocket.media

-

Emily Fromm: No Vacancy

Emily Fromm’s solo exhibition currently on display at 111 Minna Gallery, “No Vacancy,” is the painter’s comic-book style depiction of bustling corners of San Francisco.

The exhibition shows over 40 works from the California native painter who studied at San Francisco State University. Large canvases display Fromm’s characteristic graphic animation cityscape paintings. These works use thick, dark hand-painted lines with modern graphic precision to draw cartoon scenes of busy city life and local characters in recognizable corners of San Francisco. Fromm’s muted color palette evoke an immediate tone of nostalgia with tints of burnt-orange and baby-blue that capture the feeling of vintage signage, but maintain vibrancy through thick, painterly hues and playful contrast.

Storefronts, billboards and shop signs serve as the cartoon backdrop to the artist’s vignettes, creating a unique and simplified comic-book view of city life. The simple graphic designs evoke classic images of urban Americana and further add to the sense of American nostalgia.

One such work, titled That’s It, displays this comic-art vision of San Francisco. The viewer is thrust into the busy world of lights, signs, storefronts and a smattering of sidewalk-dwellers that is carefully layered upon the canvas, finding an order in the bustling chaos, and setting a street scene that feels like it could be 1950—or today.

Funeral Home (Acrylic on Found Wood | 14.5″ x 7.5″ ) The gallery also showcases a series of smaller works titled “Barry,” which are painted on found wood scraps. Here, Fromm presents slices of city life that center around a cartoon, male figure, allowing her to use her distinctive palette and animation style to explore narrative and pictorial emotion, like in Funeral Home.

Fromm’s works can be seen as the pages of her painted comic-book of San Francisco city life, capturing it’s dizzying array of visual noise, and yet crafting a comforting, nostalgic tone to the urban experience. Onlookers in the gallery can experience the little of joy of recognizing their own slice of life in a familiar neighborhood corner.

111 Minna Gallery, “No Vacancy” Emily Fromm

111 Minna Street | San Francisco, CA 94105

Show runs through Feb 23, 2019

-

Summer of Love Redux

When I moved to San Francisco to begin college nearly a decade ago, the refrain from Scott McKenzie’s 1967 hippie anthem “San Francisco” rang through my ears, beckoning me to the city by the bay with dreams of “flowers in my hair,” but I quickly learned that much had changed since the late 1960s. So I was curious to visit the “Summer of Love” exhibit at de Young museum, nestled in Golden Gate Park, birthplace of “the hippie.”

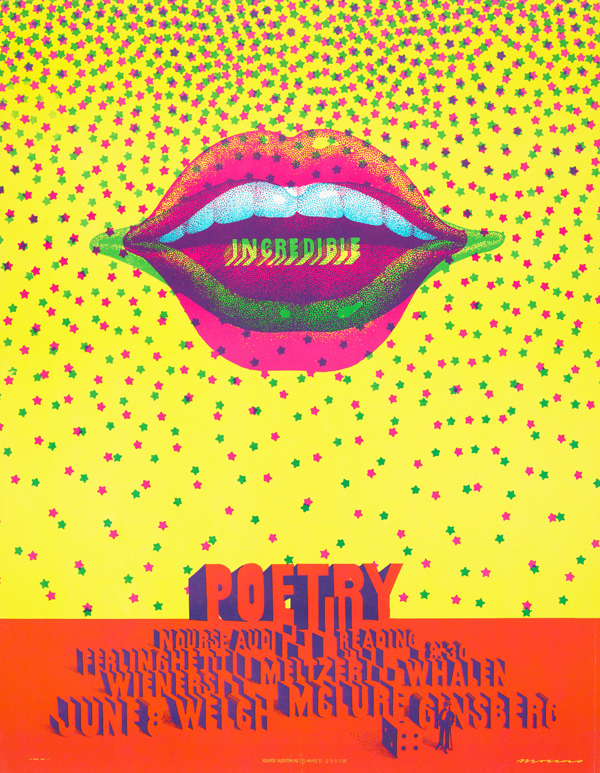

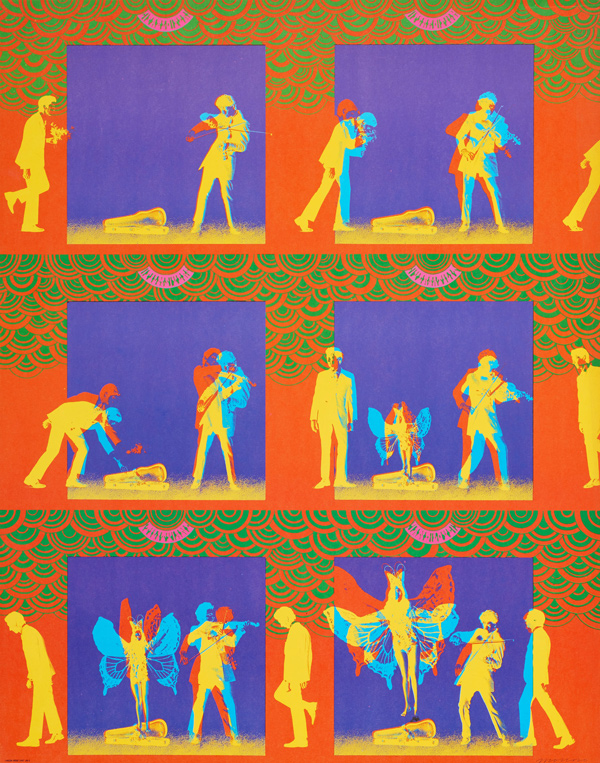

Victor Moscoso, Pablo Ferro film advertisement, 1967. Color offset lithograph “animated” poster. Haight Street Art Center. © Victor Moscoso Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco The show promises a trip down memory lane for baby boomers, and a showcase celebrating the art and aesthetics of the San Francisco counterculture of 1967—exactly 50 years later. The exhibition is curated by Jill D’Alessandro and Colleen Terry of the Achenbach Foundation of Graphic Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, with contributions by Julian Cox, chief curator of photography at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The viewer is taken on a journey through the ideals and history of the hippie movement with over 400 artifacts presenting the music, fashion, poetry, poster art, light art, film and photography of the time. Psychedelic posters and mock school certificates crafted by Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters ask, “Can You Pass the Acid Test?” Mannequins carefully poised throughout the show adorn handmade outfits that demonstrate how every aspect of life in this time period provided opportunities for exploration of the self and innovations for society at large.

Embroidered hospital scrub top, ca. 1968. Cotton plain weave with cotton embroidery (bullion knots, encroaching satin, fly, running, and satin stitches). Collection of Arthur Leeper and Cynthia Shaver Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco A canon of symbols emerges from the art, ripe with sexual innuendos, nudity, depictions of Earth’s elements, and scenes from the American West. Much of the art was steeped in Native American culture, along with patterns and colors drawn from South American and Eastern cultures—all framed against a psychedelic cacophony of neon colors, shapes and patterns, engaging the senses particularly heightened by LSD, THE drug of choice; strangely, there was a glaring absence of peace signs, flowers and paisleys.

The self-proclaimed “Hippies of Haight” forged a sovereign state within the borders of San Francisco, ruled by their own social mores, run by a barter economy, and complete with its own language, fashion and public ceremonial rituals. The intricate, nearly illegible poster art displayed across the city held coded signs, sending messages that only those within the movement could comprehend.

One poster created by Rick Griffin, of a Native American on a horse with guitar in hand, advertises 1967s historic “Human Be-in” at which a “Gathering of the Tribes” was intended to bring together the intellectual activists of Berkeley with the free-love Haight Hippies in one event. This intersection of the different subcultures of the late ’60s blooming in the Bay Area is fascinating and opens up many intriguing questions, which the exhibit fails to really answer.

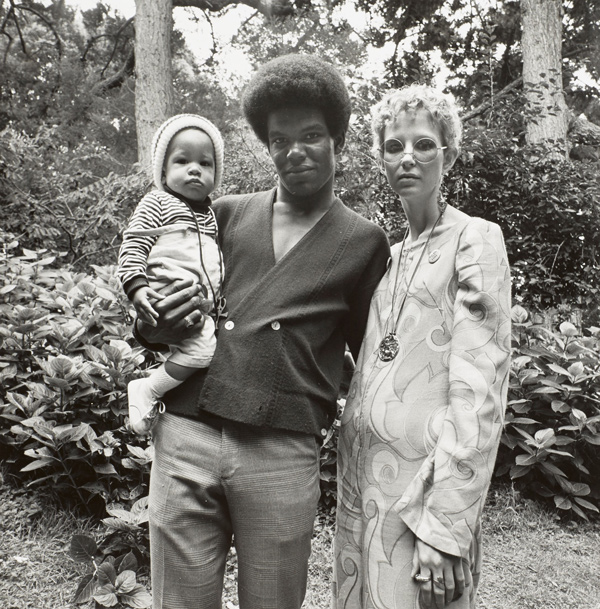

Elaine Mayes, “Couple with Child, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco,” 1968. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of Joseph Bellows Gallery. Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Outside the entrance to the de Young, mock street signs annotate intersections from the past to the present, including “Free Love” juxtaposed with “Marriage Equality,” “Hipster” with “Hippie” and “Civil Rights Movement” with “Black Lives Matter.” These seem to suggest that the hippie culture of 1967 largely paved the way for key aspects of modern society. The exhibition itself, however, lacks any real proof of these overarching claims, providing only one small room that speaks to the “activism” of the time—the Black Panthers, the Civil Rights Movement and Women’s Lib—reduced to two or three posters each. To blanket these several movements within the hippie lifestyle seems misleading, omitting the nuances of the divided subcultures that bloomed across America in the late ’60s.

While craft and creativity is evident, the exhibit left a bittersweet taste. After seven years as a San Francisco local, I am particularly sensitive to the gimmicky co-opting of the clothes and psychedelic art of the Haight Hippies to sell some cheesy sentiment of tripping out and being “groovy.” Walking down Haight Street today, head shops with neon colors painted on the wall selling shot glasses decorated with marijuana leaves are sad examples of this. A few short blocks over, you can visit “Hippie Hill” in Golden Gate Park, where the famous “Be-in” was held, and come face to face with the lingering reincarnation of this culture of runaways from 1967, in the form of packs of “gutter punks.”

Ruth-Marion Baruch, “Hare Krishna Dance in Golden Gate Park, Haight Ashbury,” 1967. Gelatin silver print. Lumière Gallery, Atlanta, and Robert A. Yellowlees. Courtesy Special Collections, University Library, University of California Santa Cruz. Pirkle Jones and Ruth-Marion Baruch Photographs Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco The hippie era is purported to be a major influence on Silicon Valley and the culture revolution of tech. Many burgeoning tech companies use the language of connectedness, using hippie ideals to justify their rapid expansion and disregard for labor regulations. The Haight Hippies would be sickened to think that they planted the seeds for the new corporate revolution of apps and startups, which deregulate labor, displace communities and feed into the widening and devastating wealth divide in our country. That the counterculture celebrated in the “Summer of Love” exhibit could not survive, let alone thrive in San Francisco today, is an irony not lost on us millennials—those of us who came to this city inspired by the very ideals and creations of that period. While it was a nostalgic enjoyable trip to a beautiful burst in time, I am reminded that the next birth of a powerful revolution like the Haight Hippies will happen anywhere but San Francisco.

The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll, at de Young in San Francisco, runs through August 20, 2017, deyoung.famsf.org

-

Jemima Kirke: The Girl Can Paint

A small crowd gathers around the entrance to Fouladi Projects gallery at Market and Guerrero in San Francisco. A doorman with a long list in his hand gives me the uneasy fear that I won’t be allowed into the opening, on account of the über-hip celebrity inside. But I tell him I’m with the press, and he shrugs and steps aside nonchalantly.

When I walk inside, every eye turns to register my entrance. The glances are meant to be casual, but the significance is obvious: Everyone is looking not at the art, but at one another. Keeping a keen lookout, perhaps hoping one of the artist’s co-stars from the hit HBO phenomenon Girls will suddenly appear, or wondering who in the small space is related to anything on that totem pole that is fame.

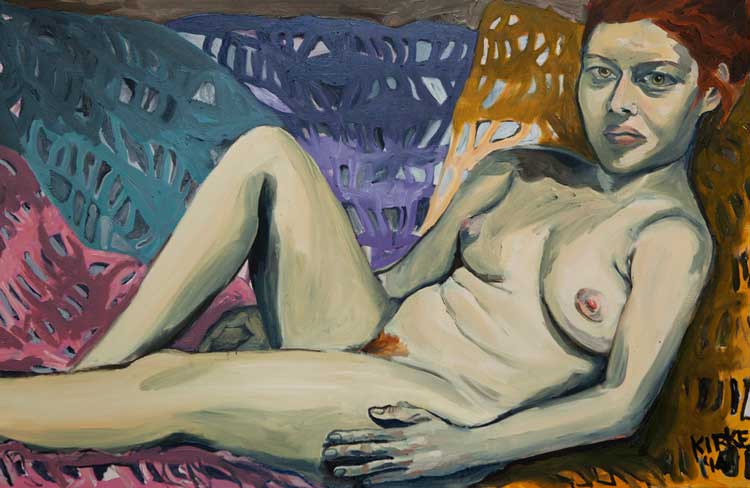

Jemima Kirke, Self Portrait (Blue), 2010 Who are these small circles of people grasping Modelos and glasses of white wine, here to see Jemima Kirke’s most recent gallery show, her first since her acting career took off alongside Girls’ creator Lena Dunham? Even at its most fashionable, San Francisco presents a tableau of grungy fashion and septum piercings. This room, however, looks like the lookbooks for Urban Outfitters, or Free People had released their slick, shiny models, straight from a shoot. The atmosphere is superficially casual, but with a palpable undertone of tension.

One wonders why Kirke chose San Francisco to debut her series of portraits, “Platforms,” although the casual mood of this small opening may have something to do with it. The gallery is filled with beautiful young ladies, handsome well-dressed hipster dudes, and well-groomed older couples oozing wealth—though it is markedly free of paparazzi, or a blockade of frantic fans. It becomes apparent that the largest, buzziest gathering of people in the room surrounds the artist herself: tiny in stature, free-spirited, answering questions, joking around, and comfortably working the room, as would any artist at their gallery opening. By the looks of it, she manages to escape her celebrity for this brief time, and appears genuinely pleased to be in a room full of people: admirers of her art, not merely star gazers.

Long before joining the cast of Girls, Kirke received a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in painting, and spent her earlier adult life developing herself as an artist. In a recent New York Times interview, Kirke made it clear that she considers herself an artist; painter first, actress second.

Jemima Kirke, Lena F, 2014 Kirke’s canvases deserve attention for themselves beyond any celebrity premium aside. They reflect a developed, insightful painter and can easily be compared with the likes of Alice Neel. Penetrating eyes peer out from the muted, pastel colors and dark, haunting shadows in Kirke’s portraits. Posed nude, the women in these single-frame epics do not lie passively on display for the male gaze. Rather, they confront you with stories of their own to tell. The naturally poised women span all walks of life, cradled in soft, colorful, yet vague backgrounds. In the portrait Sasha, deep, black shading offsets the small figure of a young girl with clasped hands, evoking the melancholy of a lonely child. In Lena F., a similar sense of contemplative seriousness is apparent in the woman sitting at her desk with her arms crossed sternly, a soft blue halo highlighting the yellow hair behind her enormous, bulging eyes.

Jemima Kirke, Sasha, 2014 Opening night attendees were excited and enthused; when I spoke with gallery owner Holly Fouladi, she hailed the show a success, with all but two pieces selling at the reception. Kirke is nothing but thankful for the opportunity to show her work, whatever the motivation, and is comfortable accepting that her celebrity may have opened this door, as she points out in The New York Times article. As the daughter of Simon Kirke, famed drummer for British ’70s rock band Bad Company, Jemima is no stranger to celebrity and its advantages. It is easy to cringe at the thought of another famous wealthy star pushing her way into the art world, forcing patrons to take notice of underdeveloped, presumptuous musings. Kirke has managed to develop her art, in spite of the distractions that lifestyle can impose.

All images courtesy Fouladi Projects