Your cart is currently empty!

Moving Forward with Women’s Center for Creative Work GRACE AND GRIT

To incarnate is to become embodied in form, and form follows function. From the outset of the year 2020, leadership at the Women’s Center for Creative Work began the task of expanding its physical form because they had had the good fortune of having outgrown their existing space. Born out of a series of successful “site-specific feminist dinner parties” in the Los Angeles area, the wishes of the regular attendees of those dinners, and a $10,000 grant from SPArt, the WCCW put down roots in the Frogtown/Elysian Valley area in 2015 as a nonprofit. The function of this form: to foster an intentional, accessible community as publicly as possible. It’s fair to say that co-founders Kate Johnston, Sarah Williams and Katie Bachler (who is no longer with the organization) were extremely successful in doing so.

One facet of this accessibility has manifested as a PDF you can download for free from the WCCW website called “A Feminist Organization’s Handbook.” The 75-page image–filled tome is a love letter to the work that they put into building their business: essays, flow charts, photos and documented processes available free and on demand for anyone in the world to download and peruse. By the act of compiling this handbook and giving the world a clear view into their mindsets as they began such a massive undertaking, they have made high-level business planning more accessible. Anyone with the will and courage can use their experiences outlined in the handbook as helpful guidelines to lay their own feminist business foundation without spending hundreds of dollars on coaches and consultants.

With this intentionality applied to their core values, WCCW’s audience and community growth was inevitable. Those core values are radically intersectional and inclusive, with the safety of women of color, trans women and disabled women given the highest priority. When put into practice, these values dictated the programming they hosted in the space: workshops, book clubs, performances and more. It’s part of what motivated the center’s new Communications & Marketing Director, Kamala Puligandla, to move to Los Angeles from the Bay Area three years ago. “I would come down to LA to visit and go to all the workshops at the Women’s Center,” she says in a video chat. “There’s this beautiful way where things collide at the Women’s Center and I’ve always been really invested in that.”

There’s so much more that can be said about the WCCW’s role in their community: partnerships with the local elementary school, partnerships with neighboring businesses, contributions to the local neighborhood council, the launch of their in-house publishing platform “Co-Conspirator Press.” Yet it was the uncertainties that came with the pandemic, coupled with leadership’s commitment to intentionality, that led co-founder Johnston to make the decision to reverse all plans of adding to their space, and move out of their beloved home of five years. (The very week they were to sign a new agreement with their landlord to expand into the warehouse next door, the state government began the mandated lockdown.) Consequently, the WCCW downsized: the staff packed up and moved out of their multi-room warehouse space in Frogtown and into a much smaller studio in Highland Park. Yet the ramifications of letting go of the former site have been startlingly positive. Resources that once went into maintaining physical space for a limited number of present bodies have been redirected to creating print and digital space that accommodates hundreds of eyeballs, remotely.

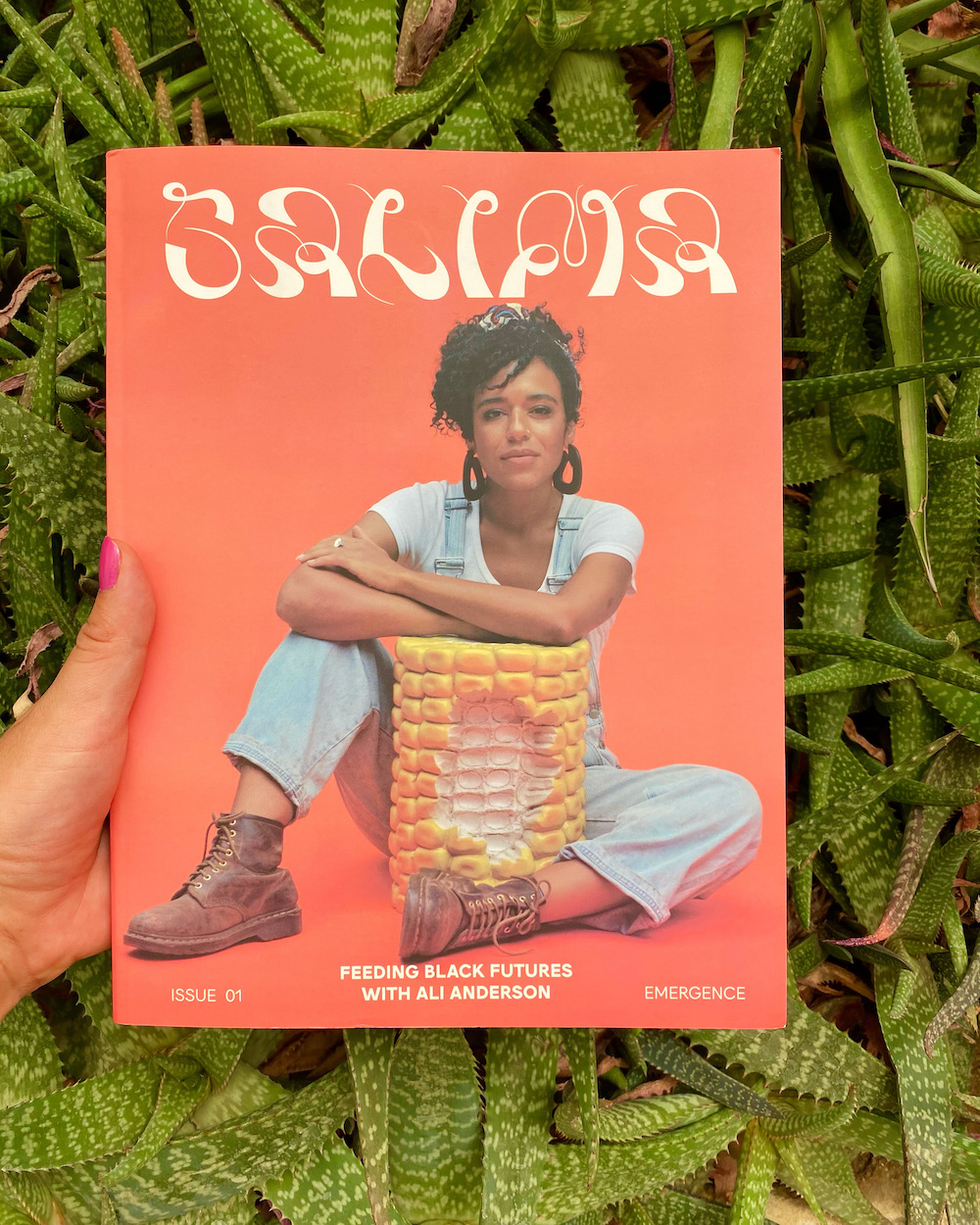

Thus, the Women’s Center for Creative Work has reincarnated: embodiment through online events has expanded its audience globally, and embodiment through SALIMA, a new print magazine just launched this year, keeps the community engaged in a material way. “It’s been a huge learning curve, but it’s been really fun and amazing,” Williams tells me. “There’s so many exciting people and voices and artists involved in all of these different ways. It feels like the [physical] space in a magazine, to me.” This is essentially a win-win for the Center and for people who—because of chronic illness, physical challenges or their location—were not always able to take advantage of the in-person programming available. This incarnation of the WCCW is the most accessible the organization has ever been.

Williams and her colleagues are working on making some of these programmatic changes permanent while tweaking others. The membership subscription they offer— which makes up 15% of their pre-pandemic income—is being restructured to reflect the changes the organization had to make last year. Responding positively to something as momentous and unexpected as a global pandemic while still serving a mission of creating, maintaining and sharing accessible feminist space takes both grace and grit, which the leadership and staff of the Women’s Center have ably demonstrated.

Editor’s Note: After publication of the article, the Women’s Center for Creative Work has since changed their name to Feminist Center for Creative Work

Comments

One response to “Moving Forward with Women’s Center for Creative WorkGRACE AND GRIT ”

Great article. Insightful, yet concise. Congratulations to the staff & members of WCCW.