Building + Becoming

By Amir Zaki

272 pages

X Artists’ Books and DoppelHouse Press

The works of Amir Zaki subtly subverts analog photography’s long-held truth claims. His photography, surveyed in the newly published artist book Building + Becoming, addresses the artist’s digital manipulation and, setting aside the medium’s presumed objectivity and fidelity to representation, invites the question, “to what end”?

Illuminated by two texts, “Stealing Light,” a conversation with Corrina Peipon, and “Addition by Subtraction,” an essay by Jennifer Ashton and Walter Benn Michaels, Building + Becoming explores Zaki’s formation as an artist, touches briefly on biographical notes and artistic lineage and examines his process while engaging in critical dialog. Ashton and Michaels also analyze the technological and post-production practices integral to Zaki’s images. At the core of their inquiry is the apparent contradiction in his claim of the Modernist tradition, via Edward Weston, and his use of a Gigapan device, which enables him to take a series of adjacent photos and stitch them together with software, resulting in works that defy the singular perspective associated with Modernist photography.

Computational imaging—to paraphrase a definition given by researcher and computational photography pioneer Marc Levoy, the use of computational methods to produce photographs that could not have been taken by a traditional camera—presents an alternate framework for considering Zaki’s technology-assisted creation of large-scale, information-saturated photographs.

The monograph is full of meticulously printed photographs that are just as beguiling and seductive as I know them to be in person, though on a reduced scale. One of the notions I have harbored—a notion the artist sidestepped when I interviewed him in 2019 about his “Empty Vessel” series (photos of California skateparks and broken ceramic vessels)—is that his work offers images of iconic California settings, which are complicated by the subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, alterations introduced through post-production editing.

In his conversation with Peipon, Zaki rejects what he calls the cynicism, hollowness and political and moralistic overtones of postmodernism. Though this description lacks definition, there is a point there about work that delivers straightforward political punchlines rather than examining the complexities and apparent contradictions of something, or engaging in open-ended inquiry. But inherent in any conversation on whether politics should influence art, or vice versa, is the question of what art can do, or what one wants their work to do.

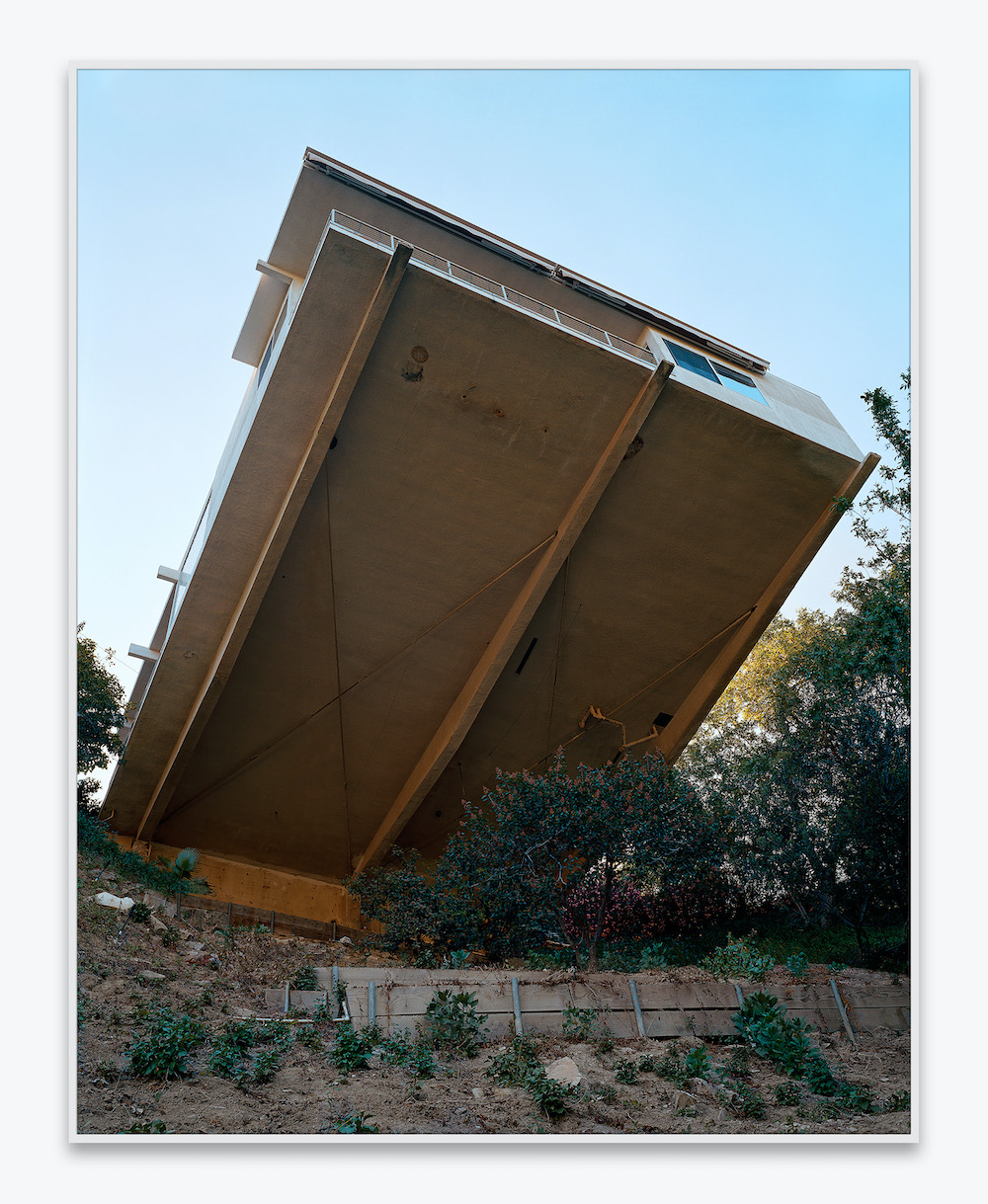

In responding to Zaki’s work, I find myself oscillating between the sensuousness of his photographs and my own desire for art to be revolutionary—that is, for art to engage in conversations that challenge and alter individuals, society and politics, for art to be at the core of vigorous debate. I see in Zaki’s work—in several of his series—a measured coolness, which combined with his explicit editing, complicates the images beyond mere manifestations of desire, as Zaki claims for them in conversation with Peipon. Think of the imposing bellies of houses (Untitled (OH_19X), 2004) perched on hillsides without support columns in his “Spring Through Winter” series, or the crumbling or close to it beachside cliffs with what appear to be private beach-access staircases (Coastline Cliffside 16, 2012, or Coastline Cliffside 22, 2012) in “Time Moves Still.” These photographs produce a kind of estrangement from the familiar and propose a darker, grittier reality that lies beyond the idyllic vision. Even while evoking Weston’s neoclassicism (“Time Moves Still,” “Formal Matter” and other series), Zaki’s photographs form a kind of speculative work. Further, they suggest a deconstruction of the attainability of success, as a state that is either just out of reach or threatening to come crashing down. As theorist and critic Fredric Jameson notes in Archaeologies of the Future, speculative vernacular creates space for a nuanced critique of social conventions, structures and politics.

Ashton and Michaels discuss Zaki’s use of technology at length. Other artists creating photographic works with technology and information systems have done so more directly to activate critique or commentary. For example, Jenny O’Dell’s “Satellite Collections” and “Satellite Landscapes” shift the point of view to planetary systems. Doug Rickard’s “A New American Picture” series, taken from Google Street View, relies on the ubiquity of Google to comment on racial inequity and privacy issues.

Arguably, all three, diverse as they are, find common lineage in Bernd and Hilla Becher’s work and in photography’s use as a conceptual strategy, as seen in Ed Ruscha’s Some Los Angeles Apartments and other series. That extends to the New Topographics artists, whom Zaki counts in his lineage (specifically the Bechers, Joe Deal and Lewis Baltz), and who also moved photography beyond the singular image and mythologizing of Weston’s neoclassicism, into the realm of documentary, taxonomies and social critique. But the contemporary moment is full of images and objects that occupy both sensuous and revolutionary spaces, simultaneously

0 Comments