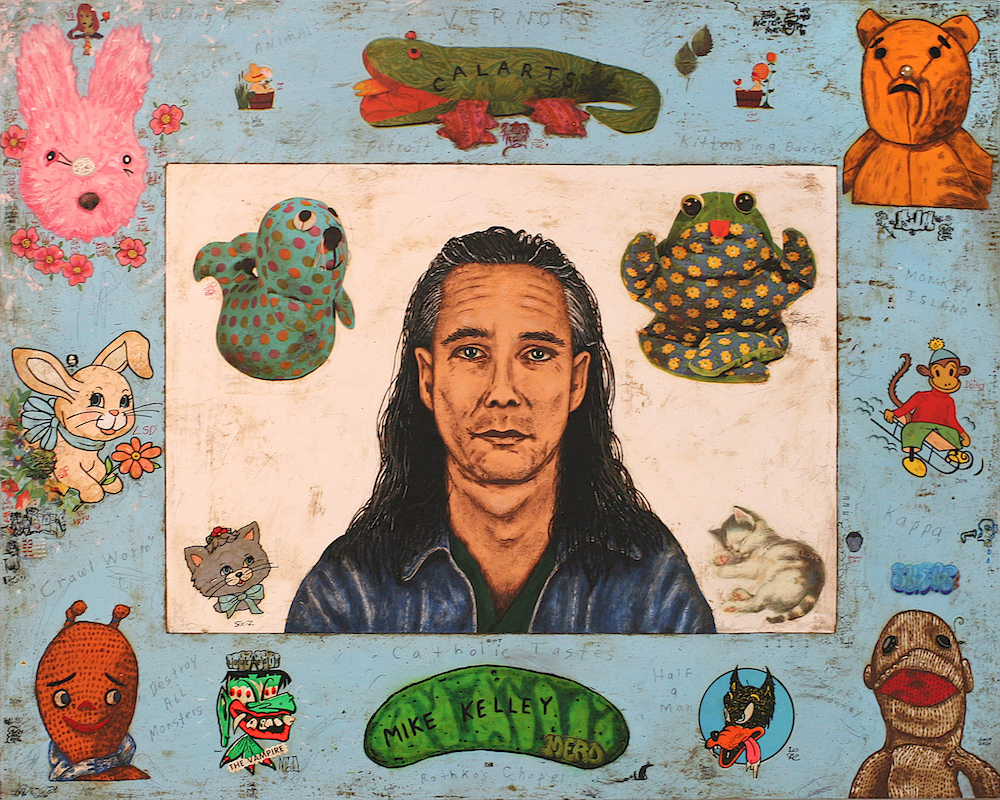

Jeffrey Vallance holds a unique position in the LA art world. A contemporary of Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Jim Shaw, et al, his work has had a comparable impact locally and internationally, while not transitioning to the industrial fabrication mode demanded by the global fiscal laundromat subdivision AKA The Art World. Part of the reason is that he’s actually from LA—the Valley, specifically—which somehow means you can’t actually represent LA to the rest of TAW.

Mostly though, it’s because Vallance responded to his initial burst of fame by embarking on an extended peripatetic global R&D expedition that had nothing to do with Kunsthallen, art fairs, or high-end public art commissions, but rather Kings of Tonga, Presidents of Iceland, and Las Vegas vanity museums. He never so much fell off The Art World’s radar as evaded capture like some international man of mystery.

Yet another factor is that Vallance writes about his own projects better than any hack critic could, with a deadpan humor and open-mindedness completely analogous to his idiosyncratic semiotic investigations. In 1995, in conjunction with a survey show at SMMOA, Art Issues Press published The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978–1994—encompassing the Tonga and Iceland adventures, as well as his first forays into paranormal reportage and, of course, the last (and subsequent) rites of Blinky the Friendly Hen—the Ralph’s fryer whose pet cemetery funeral service landed Vallance on Letterman and MTV.

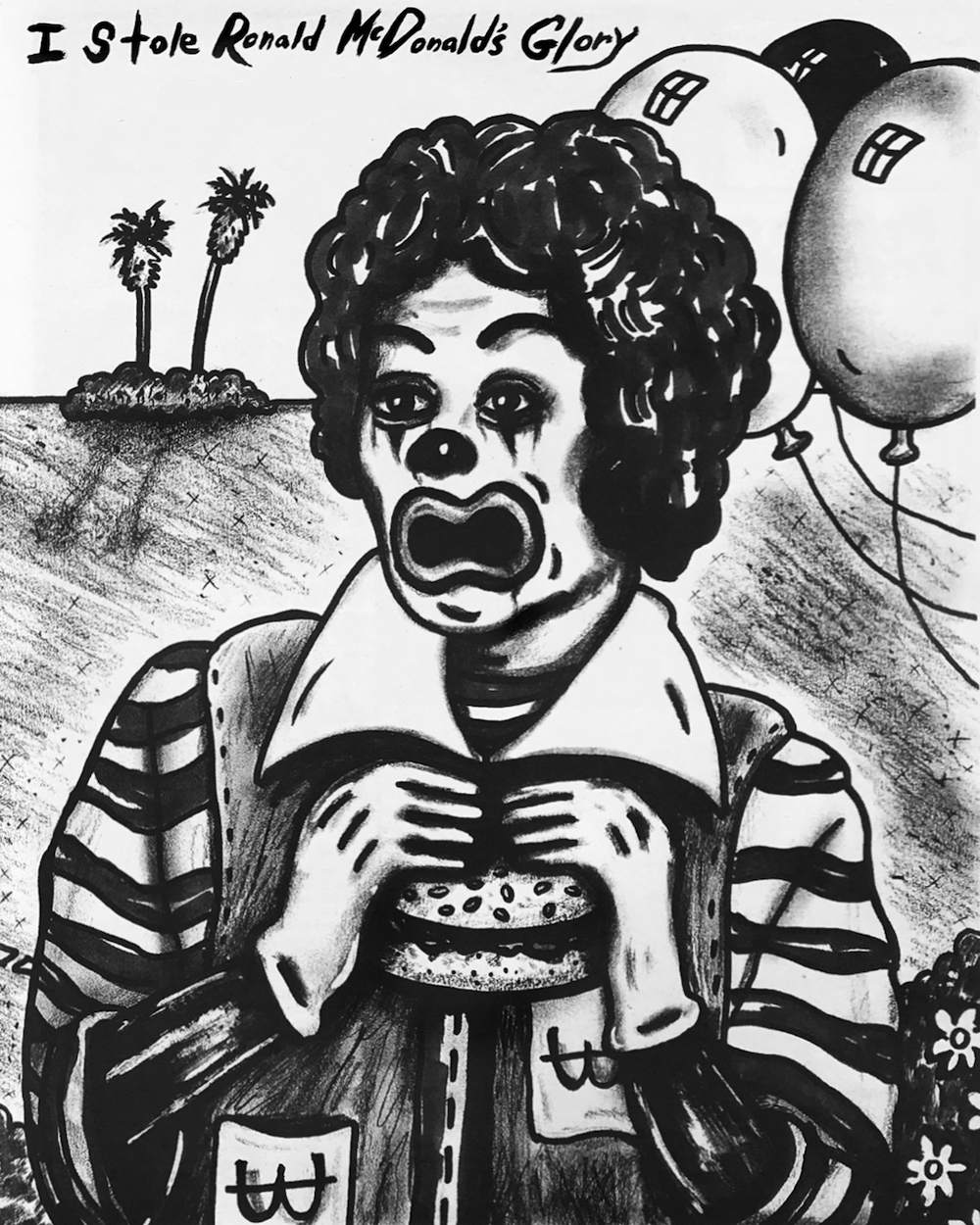

Jeffrey Vallance, The Clowns of Turin: Found on the Holy Shroud, 1996. Collage, pencil and marker on paper, 22 x 29 ¾ in. Collection of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA.

Long overdue, A Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings collects close to 700 pages of Vallance’s musings and reports from the intervening decades. That may sound daunting, but this ain’t War & Peace—nor Being and Nothingness neither. Not that it isn’t narratively compelling or philosophically deep—but it’s funny.

And entertaining in many other ways—strangely informative like the best internet curations, or like your weird uncle who gave you Charles Fort’s The Book of the Damned and a sealed vinyl copy of Spiro T. Agnew Speaks Out for your 12th Kwanzaa. A hundred little stories forming a cubist mosaic of a singular artist’s singular journey.

Art historically, the ginormous yellow tome is a gold mine, providing off-the-cuff anecdotal accounts of Vallance’s legendary curatorial interventions in various offbeat thematic museums in Vegas, while elsewhere detailing extensive cross-cultural

research into the religious, anthropological and philosophical significance of clowns.

As promised by the subtitle, much of the work addresses spirituality, religion, shamanism and paranormal phenomenology. Richard Nixon, Thomas Kinkade, Martin Luther, Charlie Manson, Ronald McDonald, the Loch Ness Monster and other spiritual teachers all make appearances. It’s not a fluke that Vallance’s curiosity-driven ideational flow is so reminiscent of an extended Wikipedia surf.

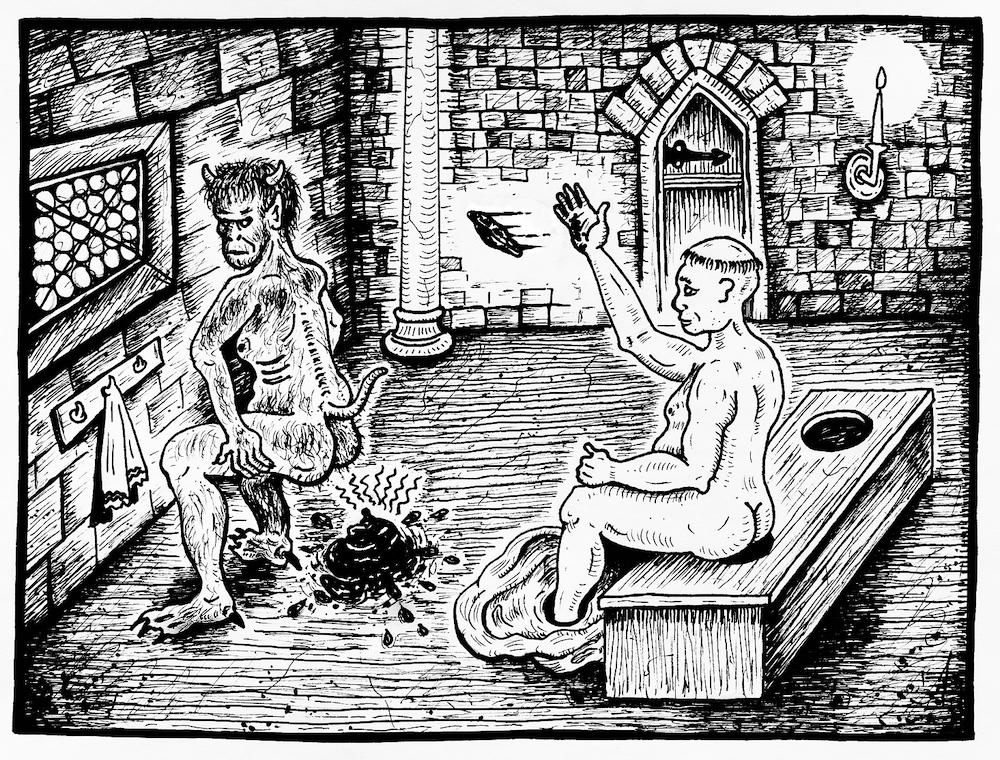

Jeffrey Vallance, Luther on the Privy, Seeing an Apparition of the Devil, 2000. Courtesy of Jeffrey Vallance and Tanya Bonakdar.

Much of Vallance’s most significant recent works have been embodied—however ephemerally—in his absurd and prolific social media activity, with Facebook groups that range from the absolutely authentic Valley Plein Air Club to the mind-scrambling Polytheistic Butt Plugs.

Consequently, Vallance’s Voyage to Extremes seems to me to be the most successful literary embodiment of the human cognitive structures that have evolved with the internet—not from imitation, but from pre-existing structural resonance. A playful, weightless curiosity may seem like a fey and inconsequential thing, but when it drifts across a border as if the border wasn’t there, watch out! That’s when Luther’s excrement hits the Devil’s fan! And that’s why the internet is still (though sadly less and less) dangerous.

In counterpoint to this ADHD-currency, Vallance has provided a newly written overarching autobiographical framework. Arranged approximately chronologically, the included materials chart Vallance’s aforementioned trips, his mythic residencies in Vegas and Umea (Sweden), and his return to the San Fernando Valley (from whence he deploys his current, peculiar global/local influence).

This interstitial narrative skeleton generates a knowing—occasionally dark, even justifiably bitter—storyline detailing the obstacles and joys of being an artist in the 21st century, from which the oddball essays radiate like feathers on a bipolar peacock. The power of art to short circuit the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune have never been articulated more elegantly.

From excrement to ecstasy, from Texas to the Arctic Circle, from the taxonomy of butt plugs to the etymology of the Tetragrammaton—all the indeterminate territories TAW tiptoes around—Jeffrey Vallance relentlessly but non-aggressively burrows beneath, collapsing rickety categorical imperatives in favor of rhizomatic ‘patacritical revelations that are equal parts Art Bell, Roland Barthes, and S.J. Perelman. Copiously illustrated.