Your cart is currently empty!

Bennett Roberts It’s About Time

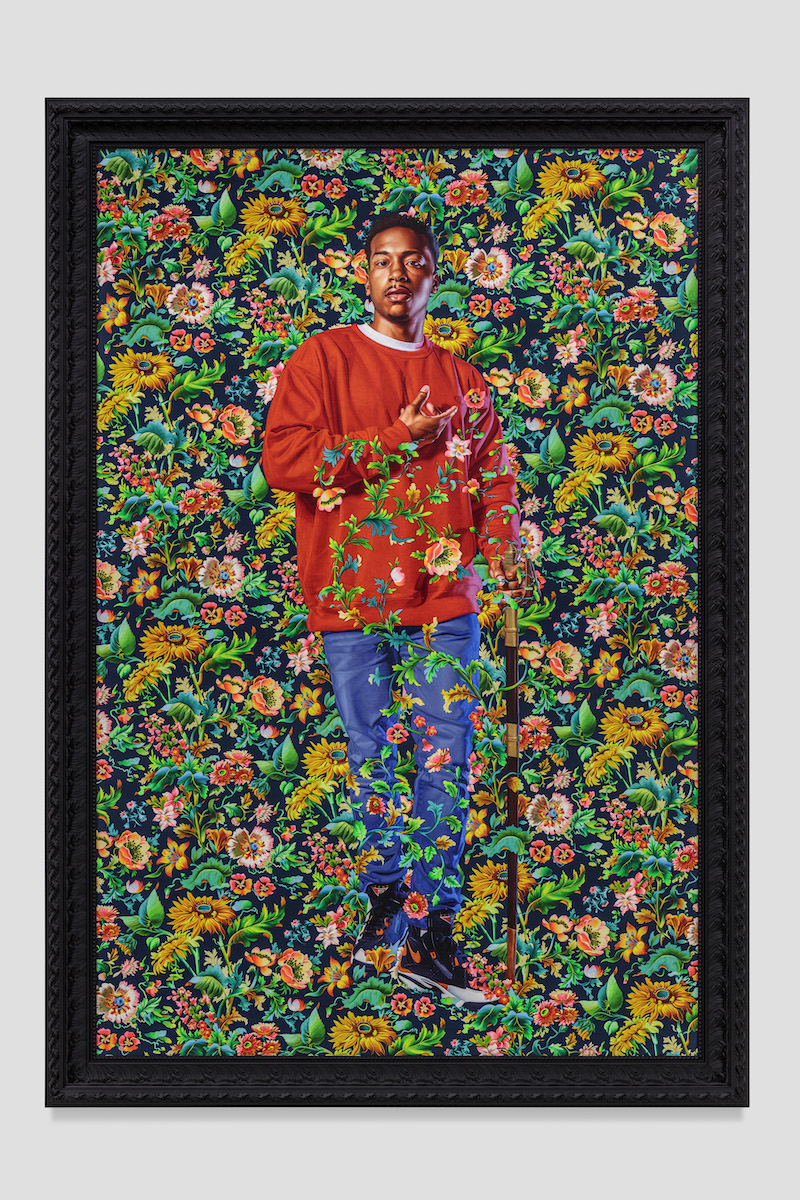

Back in 2006, I approached Bennett Roberts at his gallery on Wilshire Boulevard with a bit of chagrin. The LA art dealer had always been nothing but nice, helpful and accommodating to me as a person and as an arts writer. So my heart was heavy when I had to break it to him—before he could read it in the latest edition of Artillery—that we had panned his Kehinde Wiley show.

Roberts, unflinching, seemed to be suppressing a grin. Was it because a review in Artillery had no significance to him, or was it his absolute confidence that Wiley was already untouchable? I chose to believe the latter. He graciously invited me in to linger at the show and told me not to hesitate to raise any questions. That made quite an impression on me as a journalist; I really respected his very adult manner.

Fifteen years later, a lone Kehinde Wiley painting hangs on an empty white gallery wall, surrounded by brown-paper–wrapped canvases awaiting installation at Roberts Projects. I assumed the unopened art was Wiley’s; Roberts informed me otherwise, stating it was Amoako Boafo’s next show—the Wiley was there for a client-viewing later in the day.

The irony did not escape me as we sat down in the main gallery for the second meeting of our interview. The first time was at the Los Feliz home that Roberts shares with his wife and business partner, Julie Roberts. That was nearly a year ago (that pesky pandemic kept delaying things), and it was now September, the start of the new fall art season. Julie, a full and equal partner in the gallery, was in New York at The Armory Show while hubby stayed behind to attend to their upcoming exhibition—there’s a long waiting list for Boafo’s work—“hundreds.” The African artist who has been showing with Roberts Projects since 2018 is super-hot right now; Roberts could not afford to be away that opening weekend.

Business is going well for the gallery. Many of its artists are in high demand, and artists that have stuck by Roberts over the years are now getting their due—current art star Betye Saar for one. Roberts is in high spirits and ready to begin the interview before I even get the recorder going. He kicks off by singing high praises for LA’s current recognition as an important art center—finally. “It’s always been a great center for artists.”He pauses before acknowledging—for galleries and collectors—“not always so great.”

In the past, Los Angeles was notorious for its inferior collector-base compared to New York. Roberts recounts the LA collectors of only a few decades ago; “If they’re going to spend 30 to 50 thousand dollars or a million dollars, they’re going to buy from New York. It gave them more confidence.” That is no longer the case.

Roberts emerged in the LA art scene amidst the ’80s art-world explosion, after returning home from college in Santa Barbara. He grew up in Brentwood, a wealthy neighborhood on LA’s west side, with a producer-writer father in the film and television industry. Roberts attended Windward, “a well-known private school,” he points out, where his best friend was Richard Heller—of the Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica. In the summer of 1986, Roberts and Heller picked up where they left off and started a gallery in Heller’s father’s garage. They called it Richard/Bennett Gallery.

Within a year, they were confident enough to move into a “real” space on La Cienega Boulevard near some of LA’s hottest galleries, like Rosamund Felsen, who was debuting the likes of Mike Kelley and Lari Pittman. Richard/Bennett proved to be no slouch either: they were the first to show Raymond Pettibon, and were responsible for introducing his work to Chief Curator Paul Schimmel—who in turn put Pettibon in the famed 1992 Geffen/MOCA show, “Helter Skelter.” Running the gallery was a struggle, Roberts admits, but somehow just when they didn’t think they could cover their rent, a miracle sale would happen, or a collector would buy a few Pettibons for $250 apiece to help them out. With measured success over five years, Roberts and Heller parted ways, both continuing their own successful careers as art dealers.

RETAIN & MAINTAIN

According to Roberts, a central challenge in running a successful gallery is retaining your artists. Yes, Pettibon eventually moved on; his career skyrocketed after “Helter Skelter” and today he is represented by Regen Projects in LA and David Zwirner in New York—there’s always a bigger gallery, a better offer. Roberts concedes there’s a long list of artists who got snatched up after he invested in them. But that’s typical and expected. “It’s unavoidable,” he maintains.

Take Roberts Projects’ biggest artist, Kehinde Wiley—it is by no means the only gallery representing him. Things have changed drastically since the 1980s era, when galleries had exclusive partnerships with their artists. Roberts says he prefers the new system—a more polyamorous relationship, if you will. He concurs, “I like Kehinde showing with someone different in London, someone different in New York. I make less money and get less pieces, but those people have different collectors, different curators that are interested in that program. Artists are seen differently, depending on the program they are in.” Roberts thinks that artists showing with other galleries is not necessarily a bad thing. Another newer trend is for a gallery to have multiple spaces. Galleries don’t often want to surrender their artists to another gallery and take lower percentages (like Roberts did with Wiley). He notes, “It may actually be cheaper in the long run to have another space in New York to show that artist rather than giving the artist to another gallery.”

Roberts emphatically stresses that it’s all about retaining the talent you’ve developed. “The longer you retain it, it is perceived as important…,” he interrupts himself, “I use ‘perceive’ because everything is about time. Everything in the art world is about time. Everyone thinks it’s about popularity, success, money; it isn’t. It’s about how much time you can keep that person in play.”

Roberts believes that for an artist to have historical staying power, a cultural discussion needs to revolve around that artist and their work. Until that dialogue expands outside the art world it remains “an inside discussion.” In other words, that work will not make a wider impact, nor make it into the history books.

Kehinde Wiley’s oeuvre has crossed over to become part of a cultural discussion. Two factors play a part: his commissioned presidential portrait of President Obama and, most recently, his version of the famous Blue Boy portrait hanging at The Huntington (The Blue Boy is on loan to London’s National Gallery). Roberts Projects had a huge part in making that transaction happen. Those projects propelled Wiley into a wider cultural sphere, surpassing just the art world. Most likely, he will go down in history.

BLACK ARTISTS MATTER

The Black Lives Matter movement filtered into the art world quickly; in fact, most would say much earlier than the mainstream cultural embrace. Today, if your gallery doesn’t represent Black and POC artists, or include much diversity, you might as well be showing cave paintings. Roberts had been representing Black artists long before most galleries caught up to speed. His gallery didn’t seem to get much credit for it, but he wasn’t looking for it either. The artist roster has always been inclusive, starting with Kehinde Wiley in 2002, Noah Davis in 2006, Betye Saar in 2010 and recent additions of African artists Boafo, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe and Wangari Mathenge.

The Black artist movement is thriving right now and Roberts Projects is right on target. Alongside Wiley, Noah Davis was a big hit for them. Davis, too, is engaged in that bigger historical discussion, as co-founder of The Underground Museum, an institution created to show museum-quality work in a Latino and Black LA neighborhood that was underserved in art exposure. Davis died of cancer in 2015, at the tragically early age of 32, but had left the Roberts & Tilton gallery in 2012 (Roberts’ former gallery with partners Julie, and Jack Tilton, who passed in 2017). All ties between Davis and Roberts & Tilton were severed by then, and David Zwirner obtained Davis’ estate in 2020. (Zwirner needs to hurry and check all those boxes).

Roberts isn’t upset about that, but more dismayed about the erasure of Roberts’ involvement in developing Davis from the beginning. “I helped sell pieces to fund The Underground Museum.” Roberts pauses with quiet exasperation. Zwirner produced a huge monograph on Davis with nary a mention of Roberts. “It was unbelievable to me how the art world loves to rewrite history and make it seem like only the winners write it. Not the ones that are up-and-coming, or the also-rans.” Roberts was key in putting Davis on the map circa 2007. Roberts & Tilton were participatining in an art fair when Don and Mera Rubell (serious art collectors and clients) stopped by their booth and inquired about a painting. Roberts recalls Mera demanding: Who is this great artist on the wall? “I said, ‘It’s a brand-new discovery of mine. I think it’s terrific, I think you should get something.’ They said, ‘You know what? We’re doing [a show called] ‘30 Americans.’ And he will be the final and youngest artist we include in the show.’ And I said, ‘Thank you very much.’”(Let that go down in history—you read it here first!)

ONE PERCENTERS

Let’s face it, the art world is a rich man’s game now, and with the world’s wealth concentrated among the one percent, it’s a small playing field. “It is the game you play after all the other games you’ve played,” Roberts explains, “It is the final frontier.” He goes on, “It is the place that once you’ve made whatever fortune you’ve made and you have what everyone else has… you can differentiate yourself from all the other billionaires by collecting things that are not only great but are truly something that will enhance how you see your own position in things.” Pausing, Roberts surmises, “It’s a game of fortune.”

One-percenters have needs too. “When you’re that big, the richest people want to buy from you, because they feel secure buying from you,” Roberts says. That’s why mega-galleries like Gagosian can and do exist. At last count Gagosian had 16 galleries worldwide. In today’s global market, having art galleries around the world seems more shrewd than extravagant. Another factor, Roberts explains, “All of those businesses have a very, very vibrant secondary market—that’s truly where all the money is.” At that level, the competition is with the auction houses; they don’t care about other galleries at that point. Roberts acknowledges he’s not in that league—and is relieved not to be.

Roberts refers to what’s happening right now in the art world as a “sea change.” His and Julie’s gallery is rolling with the new system, and in fact thriving. “I don’t think that I even sell things anymore—I think people buy things from me,” Roberts says reflectively. “Zero pressure. I want the experience to be as clean and as enjoyable as possible.”

I’ve watched Roberts’ gallery remain fresh, relevant, edgy—top-notch for over 30 years. With Betye Saar’s soaring career, the recent Wiley accomplishments, and rising star Amoako Boafo on board, it is undeniably riding the wave.

Unsurprisingly, Roberts announced at the end of our interview that they will be moving from their space to La Brea Avenue. The new gallery will be three times larger than their Culver City venue. And no, Roberts Projects will not be adding another gallery; they just need a bigger space for displaying larger works and a nice showing room for their clients—where they can have an enjoyable experience considering the lone Kehinde Wiley spotlighted on the wall.

Comments

3 responses to “Bennett RobertsIt’s About Time ”

“Everything in the art world is about time. Everyone thinks it’s about popularity, success, money; it isn’t. It’s about how much time you can keep that person in play.” I realize this is from the gallery perspective, but it gives me, the artist, reassurance. Keep creating, keep showing, keep relevant, keep at it.

I agree. In a way, it applies to most things in life. Thanks for your comment.

Tulsa

Loved the article! What a terrific read. I’ve known Bennett since 1981 and showed with him and Richard way back in the olden daze. I couldn’t be more proud.