Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Los Angeles art

-

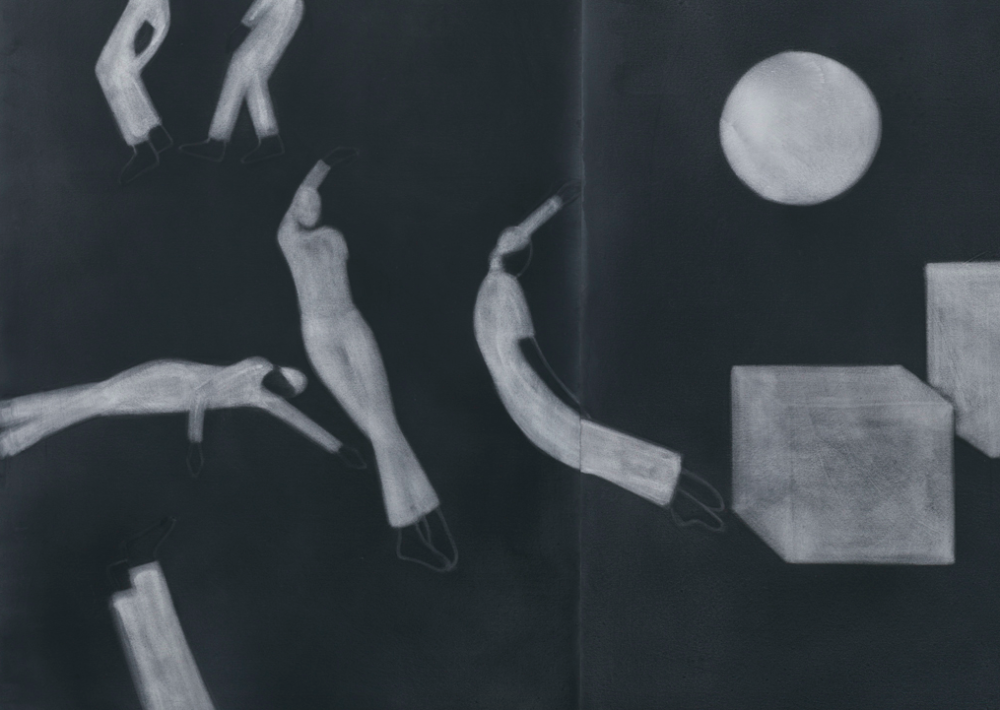

PICK OF THE WEEK: Silke Otto-Knapp

Regen ProjectsSilke Otto-Knapp’s paintings of cascading, roaming bodies feel as if they washed up on the shores of my mind like sedimentary particles— suspended and unsettled bits of matter that float and sink. Memories behave like mollusks, secreting trails of life, fading traces of the past. Clusters of silhouetted dancers appear to sprout from one another; their overlapping limbs form an intricate network tethered by some mysterious root.

Watercolor has figured into every aspect of the late artist’s practice and preparatory work. Repeatedly adding and removing paint on primed canvas, Otto-Knapp’s technical approach to painting might be described as a choreography of pigment, creating shadowy, cinereal worlds of grey. An installation of watercolor studies on paper are installed along a jagged horizon line that spans the length of the gallery wall, tacked loosely to the surface, causing them to flitter like leaves as I move across them, synchronously rippling like chimes as bodies move across the gallery.

Otto Knapp questions where the borders of life exist, imagining the strange and vast plains of life—abstract and figurative realms, psychological and physical. The silvery strangeness of Otto-Knapp’s greyscale worlds evokes the magical and longing feeling that sturs in me when I gaze upon the moon. Floating in the cosmos in one scene and swimming underwater in another, Otto-Knapp’s terrains are dark and light, thick and vaporous—figures move backward and forward, up and down, to the moon and back again. Her realms are vast, wide open plains where skies and horizons become fluid and unfixed.

Regen Projects

6750 Santa Monica Blv

Los Angeles, CA 90038

On view through August 12, 2023 -

PICK OF THE WEEK: Augustina Wang

Sow & TailorAugustina Wang’s fantastical world evokes a style of magical realism that is uniquely hers, embracing the immersive aspects of fantasy that function as a means of escapism, allowing more playful, nuanced, and expansive notions of identity to flourish. The femmes that populate Wang’s fantasyland include a cast of characters that present as alter egos, avatars, archetypes, proxies, fantasies, monsters, heroes, and anti-heroes—a visualization of the artist’s multitudes—the nuanced and numerous selves that cohabitate in one body. Beautifully rendered in oil and pastel, the protagonists that occupy Wang’s imaginative universe are full of dualities; they are emotive warriors—seductive and guarded, naked and sheathed, coy and commanding—wearing suits of armor adorned with hearts and sprigs of pink baby’s breath, delicate and muscular forces to be reckoned with.

While Wang’s fantasies and fictions operate, in part, as a form of escapism—seeking relief from the confines and pressures of the everyday—her work is also firmly planted in reality, providing a spectacular lens to communicate the elusive and abstract forces of power that loom large in the real world, helping us to untangle the power dynamics that animate and evade our daily lives and encounters, embedded in our identities, relationships, experiences, and traumas. To make sense of these gargantuan forces, the kind of imaginative thinking and playful expression of self that Wang presents feels so much more than just escapism; it feels crucial. Imaginative thinking engenders imaginative alternatives—alternatives that are critical to our mutual flourishing and evolution, both as individuals and as cohabitants on Earth.

Sow & Tailor

3027 S. Grand Ave.

Los Angeles, CA 90007

On view through May 13, 2023 -

GALLERY ROUNDS: Life By Design

Gresham Gallery at San Bernardino Valley CollegeIn a planet crowded with polarizing paradigms, is it possible to contribute aesthetically to larger conversations about culture and existence? Life by Design, a group show currently at the Gresham Gallery at San Bernardino Valley College (SBVC), masterfully interrogates this possibility. Life by Design curator and SBVC art instructor C. Ian White democratizes access to contemporary gallery and museum practice. The son of Charles White—one of the 20th century’s foremost and prolific figurative art masters— curator White’s curatorial vision assembles a collage of internationally accomplished blue-chip artists from the previous century into a cohesive visual statement relevant for our current period.

Life by Design installation view, 2022. Courtesy of Gresham Gallery at SBVC. Prescient issues such as isolation, emptiness, and environmental anxiety are addressed in three-dimensional works by Kirsten Stingle Stephen Braun and Seiji Kunishima. Relatedly, two-dimensional works by Thelma Johnson Street, Romare Bearden, Kerry James Marshall, Andy Warhol and Ben Sakoguchi seep messages about culture, commodification, and consumerism.

Two works in particular hit the curatorial bullseye. First, is Virgil Abloh’s Receipt Rug, IKEA Collaboration (2019). Abloh’s vanilla colored textile work addresses the hegemonic belief systems exerted by the capitalistic ruling class over what it truly means to furnish a space. His piece asks how a first-world, filthy rich nation can allow rampant houselessness to flourish so much it is nearly a country within a country — the wealthy elite being a sovereign body engaged in economic voyeurism of the so-called have-nots.

Life by Design installation view, 2022. Courtesy of Gresham Gallery at SBVC. The second stand-out work is Shepherd Fairey’s Make Art Not War (2017), which mirrors the message of Edwin Starr’s 1970 Motown hit song War. A bold lithograph on paper, Fairey’s Make Art Not War upsets the Western imperialistic narrative popularized through disinformation campaigns. By celebrating the creation of art Fairey empowers the unfiltered and unplugged.

Ultimately, Life by Design asks to be consumed by those who in the, words of saxophone great Charlie Parker, “Hear with their eyes and see with their ears.”

Life by Design

Gresham Gallery at San Bernadino Valley College

April 11, 2022 – July 28, 2022

701 South Mt. Vernon Avenue

San Bernadino, CA 92410 -

GALLERY ROUNDS: Nathan Redwood and Senon Williams

PRJCTLAA pair of exhibitions each in their own manner engage with formula and intuition. In Portraits: Invented Subjects and Divergent Styles, 90 works (all acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 inches, 2015-22) by Nathan Redwood form a tight procession flanking the walls in grids and groups. The overall effect despite a pure onslaught of visual information is holistic; each work is indeed an aesthetic and stylistic universe unto itself, yet crosscurrents of palette, gesture, and patterning motif create just enough continuity to cohere across the panoply. Less a series of actual portraits and more an alibi armature on which to hang years of wild, improvisational, art historical experiments in color and texture. A certain fondness for dusty ecru and radiant teal, a joy taken in rustic pointillism, a special way of mark-making that is neither line nor brushstroke but a fusion of the two — these elements appear and reappear across technicolor harlequins, moody maidens, charismatic characters, and more abstract arrangements of architecture and objects that approach symbolic portraiture.

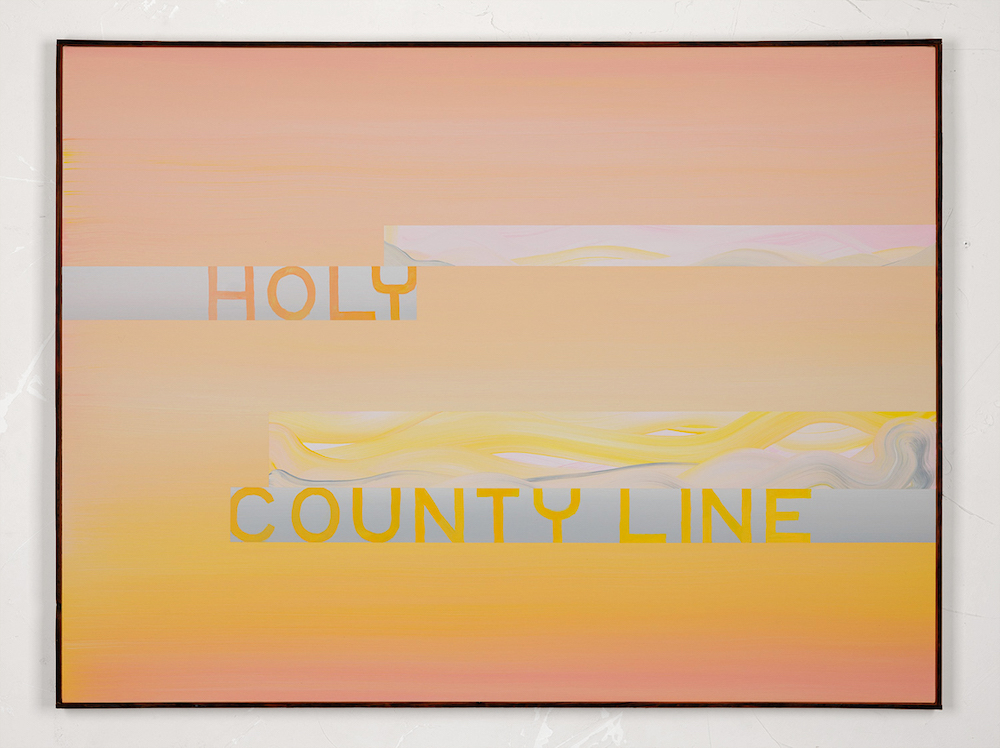

Nathan Redwood at PRJCTLA, installation view, 2022. Courtesy of PRJCTLA. In Holy County Line, Senon Williams visits paintings, works on paper, and sculptures that all in some way incorporate text set against either organic color wash grounds or the reworked materiality of found objects, creating a balance of incongruities that are ambiguous but behave as though full of meaning. The eponymous “Holy County Line” (acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 inches, 2022) offers peachy Agnes Martin-esque atmospherics; “Money for Dope” and “Lay Low Occasion” (acrylic on canvas, 24 x 30 inches, 2022) are darker, evocative of mountain ranges and cloudy skies — the brain wants to articulate the relationship between the image/mood and the text/narrative, and its struggle to do so is, in many ways, the work’s deeper subject. For sculptures, pun-emblazoned benches and flashcard interventions in game sets and freestanding anti-monoliths create moments of humor and subversions of function that serve to both highlight the appeal of repurposed materials and demonstrate that art can live anywhere.

Senon Williams, Holy County Line. Courtesy of PRJCTLA.

Senon Williams, installation view. Courtesy of PRJCTLA. Nathan Redwood: Portraits Invented Subjects and Divergent Styles

PRJCTLA

May 28, 2022 to July 2, 2022Senon Williams: Holy County Line

PRJCTLA

May 28, 2022 to July 2, 2022 -

GALLERY ROUNDS: Monica Wyatt

MorYork GalleryMonica Wyatt’s “c u r i o u s e r – Assemblage Creations from Wonderland” is a magical mystery tour of immersive experience. Wyatt offers work that is, at turns, whimsical, wild, and ephemeral. Created of repurposed materials, her detailed, intricate work floats and gleams, incandescent, dazzling sculptures created in large part during the pandemic, and transcending any sense of confinement.

Some works resemble otherworldly plant life, most obviously with her 2021 work, including Cactus on Mars, a spiky beauty made of cable ties, wire, and enamel paint; Fall Silent a flowing vine of wire, glass vials, ceramic electrical components, and cork springs; as well as in the dangling ropy wires and incandescent pods of Years Come to My Eyes #1. Her hive-like Years Come to my Eyes #3, sparkles with shiny steel sewing machine bobbins and blooms with multi-colored wire and buttons. The Velvet Moss of Caterpillars uses salvaged wood as its fallen-log-like base for electronic capacitors and connectors seemingly slithering against an intricately and deceptively soft-appearing surface. The titular Curiouser resembles a vase of strange pod flowers, their centers rubbery floor protectors while glass lenses and acrylic baubles shine, forgotten jewels on the circular What You Left Behind (2019).

Monica Wyatt, The Velvet Moss of Caterpillars When Shadows Chase the Light (2018) is a sparkling, bubbly suspension of 5000 acrylic globes, high-bay lenses, and 24,000 white nylon hairnets, alight with LED, vast and dream-like. Hexagonal patterns fascinate in 2020’s A Cosmic Blink, and The Far Side of a Cloud (POR). 2016’s Anatomy of a Cloud bursts from the wall, a mix of African beads and organ parts.

Monica Wyatt, The Far Side of a Cloud (POR) Also working in jubilantly repurposed materials is artist and gallerist Clare Graham, whose work dovetails seamlessly with Wyatt’s, both artists creating luminous, transformed, transformative art. Graham’s vast collection includes delicately elaborate bead chandeliers, an aluminum pull-tab-covered bench and chair, and delightfully openable tiled cabinets and hutches, with varied interiors containing mirrors, a holographic image, graceful scallops of metal wires, or collections of crystal balls, old books, and a safety-pin sculpture.

MorYork is located at 4959 York Blvd., Highland Park. Through May 7th; 2-5 T-Th; 12-4 Saturday.

Photos by Genie Davis.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Abraham Cruzvillegas

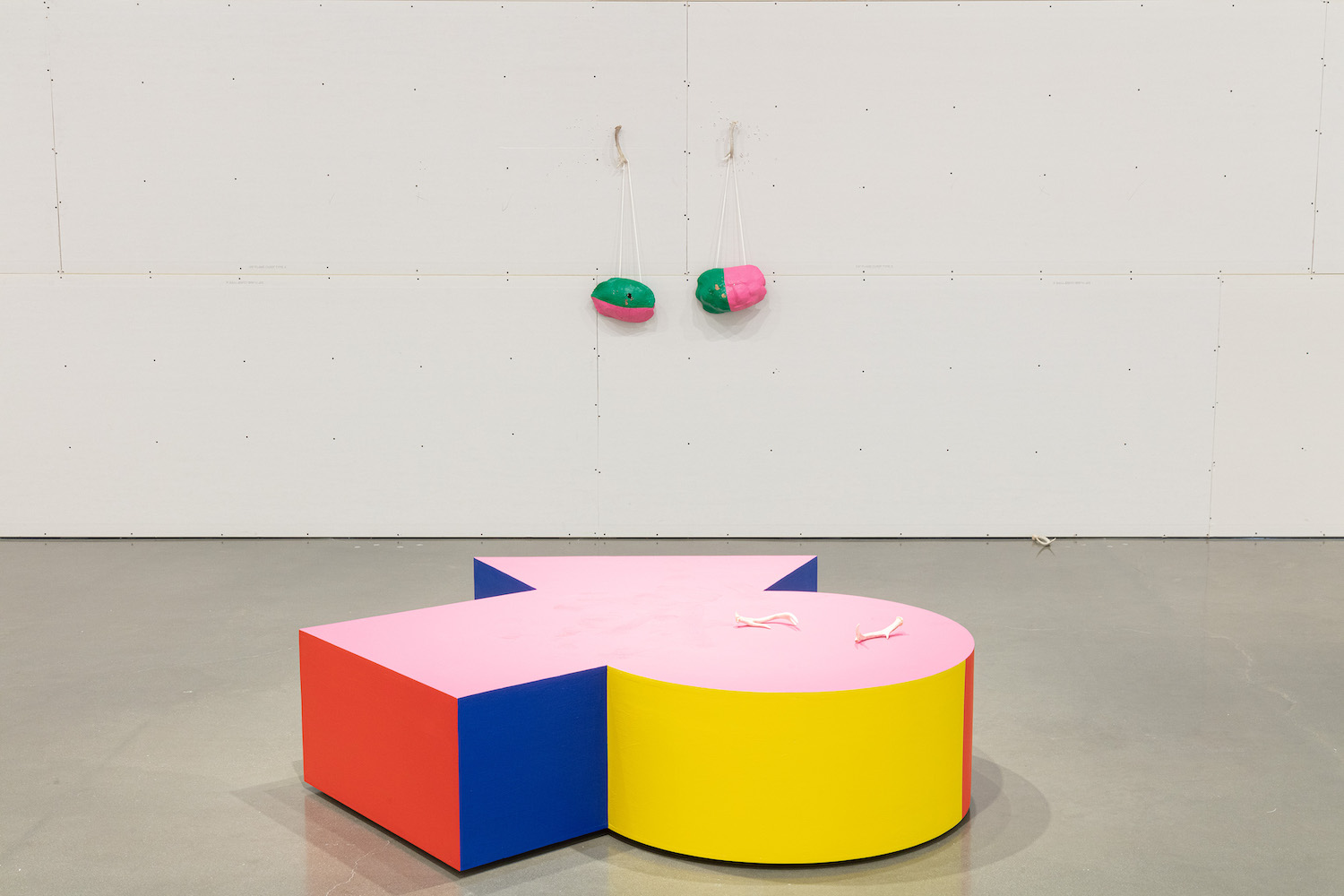

Regen Projects, Los AngelesConsider the rhythm of poetry, the speaking voice and the eye moving across the page, the mathematics of strict iambic and hendecasyllabic verse pressed into the service of unruly love and nature. The pace and structure of power of three is eternal, the optical advance and retreat of colors in complement and conflict keeps the eye in motion, and the organic beat of handmade drums moves the mind and the feet. The physical rhythm of the body engaged in labor, sweeping a mop across a gallery floor, wielding a mop as paintbrush to lay down wide, wavering routes of pure color — at some point, it will become necessary to confront the movement of capital and its role in the production of objects and the guiding of interests as ideas progress art history. All of this and more converges in Abraham Cruzvillegas’ remarkably forthright and elusive Tres Sonetos (Three Sonnets).

Abraham Cruzvillegas, Tres Sonetos Opening Performance (video still) at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Saturday, March 5, 2022. Video courtesy of Regen Projects. The exhibition was inaugurated with a performance by the artist involving painted shell-and-antler drums, their beats punctuated by poetry read from atop each of the three wooden stage sculptures, and finally the pounding of the antlers into the wall, from which the drums now hang. Those drums, the three fanciful wooden set-pieces, a series of three photographs of the artist in face paint and a trio of large-scale paintings are all connected by a specific, refined but eccentric palette of pink, green, yellow, gray, and blue. The sculptures and the paintings were executed on site at the gallery, and the paintings especially are assertive, almost boastful, in their display of the labors that generated them. In their appearance and the energy of their linear armatures they evoke Sol Lewitt’s wall drawings and in particular the line paintings he notoriously signed on the diagonal. Cruzvillegas shares this puckish taste for obscuring intentions and thwarting preciousness, undermining the logic of capital by forcing viewers and collectors into making choices about which way is up, puncturing the passive haze of consumption without responsibility.

Abraham Cruzvillegas, Camécuaro γ, 2022, Silkscreen on cotton handkerchief, Handkerchief dimensions:

18 x 18 inches. Image courtesy of Regen Projects. Photo by Evan Bedford.The way Lewitt’s larger wall drawings were intended to be executed, often at a later date, by others whose job it would be, similarly to Cruzvillegas prioritized the idea over the special hand of the genius, separating the work of execution into its own category of action, thus highlighting labor and in this way further scuttling the capitalist fetish for the “original” or the rare. All of this is as appealing to Cruzvillegas as the dulcet pounding of lines of the Concha Urquiza poems that inspired the show and which were performed at its opening. She was Catholic and a communist, and her legacy was one of change and possibility nurtured in the heart of classical form. A perfect muse for this exercise in rhythm and meaning.

Abraham Cruzvillegas: Tres Sonetos

Regen Projects, Los Angeles

March 5 – April 23, 2022

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Sonya Fe

Riverside Art MuseumSky-rocketing gasoline prices accompanied by worries of war in Ukraine even as the planet attempts to turn the pandemic corner is more than enough to hold happiness hostage. However, Sonya Fe’s exhibition “Are You with Me?” at the Riverside Art Museum recaptures the playfulness of childhood youth where every day seems like holiday stay-cation, binge-watching Saturday morning cartoons and humming Sesame Street’s theme song while snacking on a jelly sandwich. In this 21st century, anxiety has become the kryptonite for a memorable childhood; however, Fe’s work courageously honors and affirms youthful human experience emersed in hope.

Her skillful interpretation of the figure in these oil paintings mirrors the Mexican masters: Khalo, Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros, in a first reading of these works. However, the significant difference is Fe’s conscious choice to focus on children as primary subject matter, aesthetic intentionality celebrating the soul of these little ones.

Even While Sitting, Kids are Kinetic with Energy ( 2018) depicts a girl adorned in an ivory dress with a puzzled yet impatient expression indicating frustration in being still while sitting in a sky-blue and cherry-red chair. The puppies held in each hand with a leash are standing, ready to scurry away. The contrasting hurricane swirl of plants—ranging from popsicle orange to Christmas-tree green—with the momentarily peaceful child suggests that rambunctiousness has a beginning. In fact, similar to Cristina Cárdenas’ Yo Soy/Myself (1996), this depiction of the sitting child reflects Fe’s proficiency at communicating much with simplicity.

Installation view, Sonya Fe “Are You with Me?” at the Riverside Art Museum, 2022. In Grandpa’s Truth ( 2020), Fe’s versality shines through with a hint of cubism similar to Charles Alston’s Family (1955) in her portrayal of two caramel complexioned children. The young boy is wearing a snowy shirt held in place with coffee-colored suspenders as he proudly holds a book at his side titled Black History. Next to him appears to be his sister in a pearly neutral dress staring as if wanting to greet viewers. The red chair dances compositionally against the pineapple-yellow strokes shaping the room’s wall.

Ultimately, this show contributes to the dialogue surrounding contemporary Chicana and Chicano art. Sonya Fe’s exhibition is a must-see.

Sonya Fe: Are You With Me ?

October 16 2021-May 29, 2022

3425 Mission Inn Avenue

Riverside, CA 92501

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Ed Templeton

Roberts ProjectsDeceptively clean, simple, and filled with Southern California light, Ed Templeton’s new exhibition “The Spring Cycle” explores life in a suburban Southern California beach. And it has a deeper context: a critique of the banal isolation that often permeates suburbia.

Templeton’s eighth show at Roberts Project narratively depicts and dissects Huntington Beach, his hometown. Doing so, he also takes on some of the politics of the area and goes deeply into the lack of connection that divides American life everywhere.

Both the larger acrylic on panel paintings and the smaller works on paper (all works created in 2020 and 2021) are strikingly awash in sun and ennui, realistic in execution, highly realistic with a flat style that still includes dimensional shadows. Despite their realism, they border on the absurd in subject.

In Newland Avenue, (48” x 48”) a young woman in a bikini waits to cross the street, oblivious to a young child reaching for an overturned toy car—the child seems steps away from the danger of running into the street. The denuded landscape has an ominous overtone of neglect—a tree stump, a discarded cup on an electrical box, a shopping plaza with a lone vape store and nail salon.

Installation view, “The Spring Cycle,” 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles, California. Photo: Paul Salveson. In A Peak into the Rabbit Hole, (36” x 48”) there’s a similar sense of banality and danger. A boy peers through a hole in a concrete block fence where the area is taped off as the top of the wall is crumbling. Cutting through the alienation of suburban life seems to be a hazardous proposition.

That alienation is brought home with special poignancy in Pandemic Summer, Suburbia 2021, (12” x 16,” acrylic on paper). Clad in a bathing suit, a girl rides a bike past a man sitting alone at a bus stop; another man is collapsed on the ground. A nearby sign recommends “social distancing”—a caution that hardly seems necessary here.

Along with paintings and drawings, a showing of Templeton’s own photographs that inspired the painted work accompanies the show in another gallery.

Roberts Projects is located at 5801 Washington Blvd, Culver City. The exhibition runs January 22nd – March 5th. Reception: March 5th 4-7 p.m.

-

Shoptalk: LA Art News

Art Fairs, Breakout Artists, and More.On a Roll

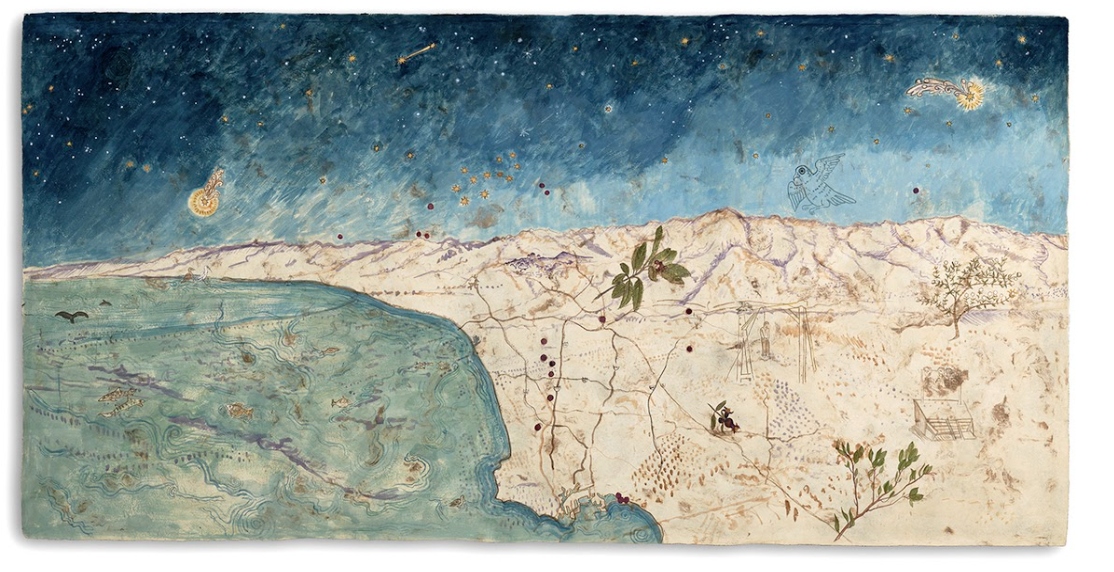

LA artist Sandy Rodriguez is having a very good year—her work is currently in a solo show, “Sandy Rodriguez in Isolation” (through April 17), at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, TX, plus she’s part of two major exhibitions in the LA area, “Borderlands” at the Huntington Museum (through fall 2022) and “Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes” (through June 12) at LACMA.

I love the fact that everything she uses to make her work is carefully considered and contributes to the meaning of the work. For “Borderlands” she created a monumental 8’x8’ map of greater Los Angeles which mines deeper histories of the land. That map—YOU ARE HERE / Tovaangar / El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Porciúncula /Los Angeles—shows topography, flora and fauna, language and stewardship over time. This work, like much of her oeuvre, is on amate paper, made by a hand-process that predates the Conquest, or the coming of the Spanish to the Americas. It is made from tree bark in a traditional manner involving being pounded by lava rock to bind the fibers. “At the time of the Conquest, it became illegal to make this paper or work on this paper,” she says on a museum video. “If it’s outlaw paper, I’m going to use this paper and tell that story on this sacred paper.” Rodriguez also uses pigments that are mineral and earth-based—in the gallery, there’s a showcase featuring the pigments she uses.

The solo at the Amon Carter features 30 new works-on-paper she created during her stay at the Joshua Tree Highlands Artist Residency. It was during a turbulent time of COVID rising and nationwide demonstrations against police brutality, and she looked to the natural world around her to guide her. Studying and collecting native plants, she incorporated them as raw material for this series, which includes landscapes, maps, scenes of protests, and botanical studies. A big congratulations, Sandy!

Fairs Bouncing Back After Pause

Frieze returns to Los Angeles after a pause last year due to you know what. This time (February 17–20) it’s bound for a new location next to the Beverly Hilton, in a new structure designed by Kulapat Yantrasast and his firm wHY, which created the white tent at previous Frieze LA on the Paramount lot. Leading the return is Christine Messineo, newly appointed director of Frieze LA and New York, with the LA edition featuring over 100 galleries from 17 countries. Also new will be a public art component, Frieze Sculpture Beverly Hills, in Beverly Gardens park, with support from the city of Beverly Hills.

Among the galleries at the main event will be 38 LA-based galleries—(the usual suspects): Blum & Poe, Jeffrey Deitch, Gagosian, David Kordansky, L.A. Louver, Regen Projects and Various Small Fires (VSF). They will be joined by first-timers Bortolami, Sean Kelly and Galerie Lelong & Co., as well as New York returnees Paula Cooper, Gladstone, Marian Goodman, Gallery Hyundai, Pace, Maureen Thaddaeus Ropac, and David Zwirner. So, okay, a pretty heavy-duty array. Given the rather riotous success of Art Basel Miami in early December, Frieze should also benefit from people eager to gawk and gab and buy gobs of art.

Looks like other art fairs will also sprout around that time, including Felix returning to the Roosevelt Hotel, also February 17–20, and a new fair, the Clio Art Fair for “independent artists,” at the Naked Eye Studio on the same weekend. No news on any dates for Art Los Angeles Contemporary, which made an inspired move to the Hollywood Athletic Club in 2020. Apparently, that cost a bundle to launch.

Meanwhile, Intersect comes to Palm Springs Feb. 10–13, with exhibitors, talks and programming at the Palm Springs Convention Center and some other desert locations. Specifics aren’t out yet as of this writing, but in a brief chat director Becca Hoffman conveyed their commitment to building community and connecting with the local art ecology. Hoffman was formerly director of The Outsider Art Fair. Intersect has already debuted in Aspen and Chicago.

At the start of the year the long-running Los Angeles Art Show returns to the LA Convention Center, January 19–23, after getting off-schedule in 2021 with a summertime session. This show covers both modern and contemporary art, and is making concerted efforts to be more relevant with special programming, this year concentrating on the global environment. The new direction is being led by Kassandra Voyagis. “With a focus on the global effects of humankind on the planet,” she said in a press release, “It is the right time to present voices from around the world, and I am excited to facilitate this wonderful event.”

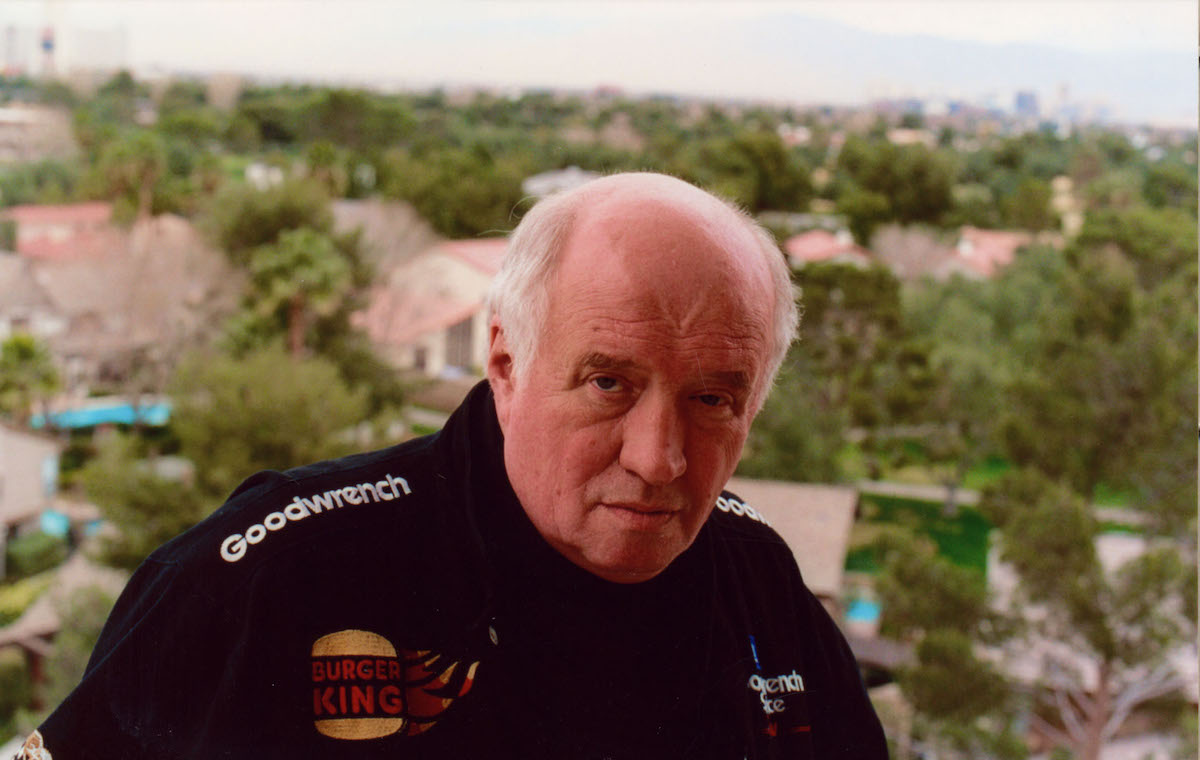

Photo by Libby Lumpkin. We Love You, Dave!

Dave Hickey (1938–2021)

Dave Hickey, who died this past November, at 82 (about a month to the day this is being composed), was in many ways a godfather to Artillery, friendly with its editor and several of its contributors, but more importantly, in his intellectual scope, irreverence, eclecticism and unflagging pursuit of fresh beauties in every medium and across a richly diverse cultural terrain, a guiding critical spirit. Long after the Cool School’s halcyon days (he wrote the catalog essay for Ed Ruscha’s SFMOMA 1982, I Don’t Want No Retrospective) and his years on the rock ‘n’ roll caravan—including songwriting in Nashville, writing for Rolling Stone, and backing up Marshall Chapman’s rhythm section—his essays for LA’s Art Issues tore a swath through the domain of art and cultural criticism as wide and as glittering as the Vegas Strip. His epochal 2001 SITE Santa Fe biennial, “Beau Monde” (which I covered at the behest of Artillery’s editor), was, among other things, a material and architectural dramatization of the art conversation he had himself ignited, and which not so incidentally foregrounded Los Angeles as an art and creative capital. It gives us no small joy to carry his legacy—“bad acting and wrong-thinking;… courageously silly and frivolous;… enthusiastic, noisy;… seductive, destructive”—forward, because (as he said in the same essay), “art doesn’t matter. What matters is how things look and the way we look at them in a democracy …—as a forum of contested values where we vote on the construction and constituency of the visible world.” —Ezrha Jean Black

Other News

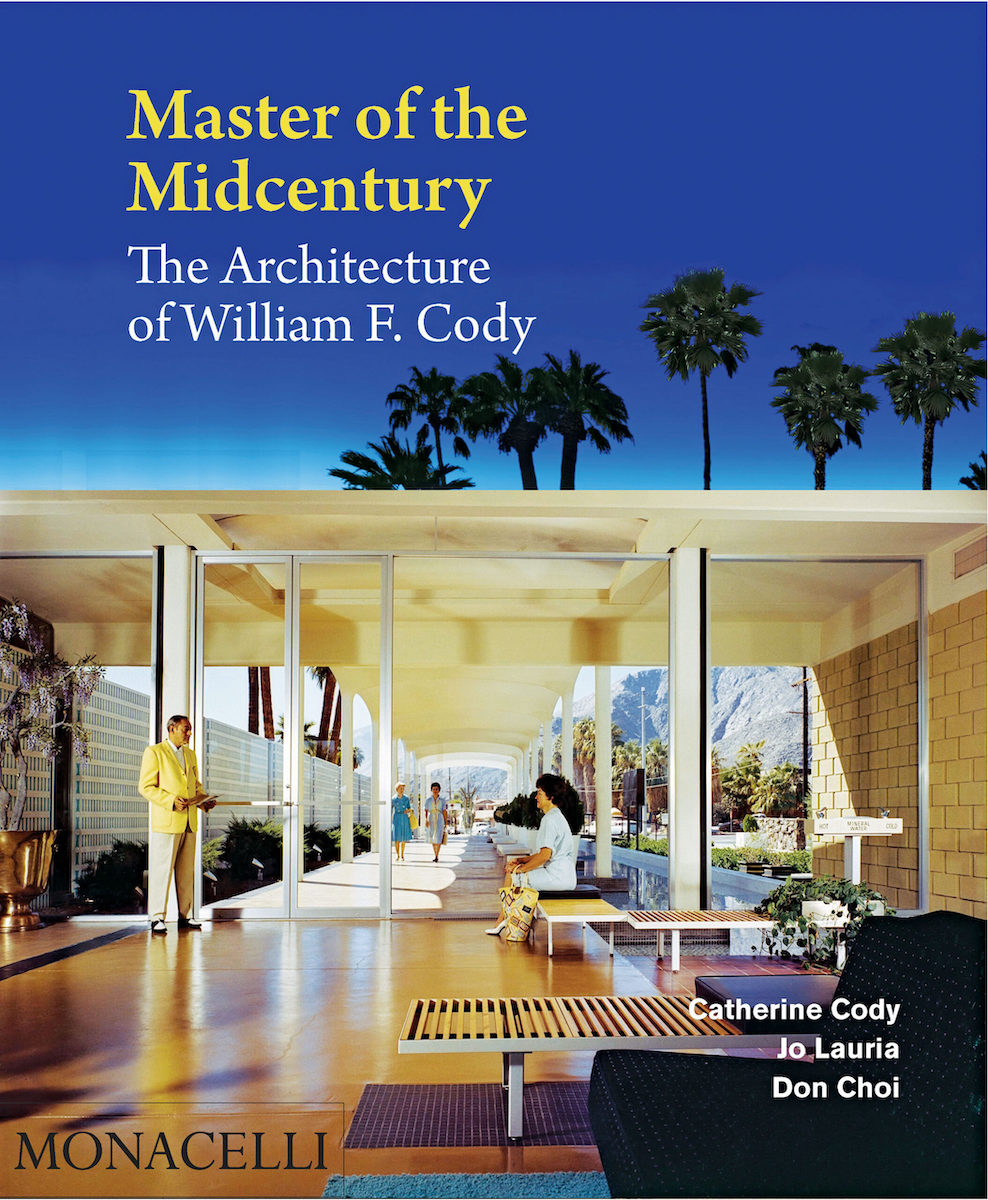

One of the top five art books of the year cited by NPR’s Heller McAlpin is “Master of the Midcentury: The Architecture of William F. Cody,” authored by Catherine Cody, Jo Lauria and Don Choi. Cody helped create the sleek postwar Palm Springs look and designed a number of celebrated buildings still standing, including the Del Marcos Hotel and the Palm Springs Public Library. Yes, you can stay at the Del Marcos and enjoy the updated Mid-century furnishings and the central swimming pool outside your door. Catherine Cody is his daughter. Other books on the list are “Woman Made: Great Women Designers,” “Bird: Exploring the Winged World, “The Unwinding: and other dreamings,” and “William Morris.”

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Leigh Salgado

Launch Gallery“As the World Turns” is an apt title for Leigh Salgado’s fourth solo exhibition at Launch Gallery. Many of the graceful works are circular, globe-like. A lush world of beauty that also evokes ideas of the circular nature of life: our annual passage around the sun, and speaks to the power of female strength in nature.

The painted, collaged, and cut-paper works are intricately mandala-like. The layers of each hand-cut paper and acrylic piece are as delicate as butterfly wings held in place by tough yet fragile spider webs.

Leigh Salgado, In & Out, 2021 Creating almost impossibly perfect patterns in medium and palette, Salgado juxtaposes the transitory nature of life and its abiding existence, and both the poignancy and power of its beauty.

Her lacy patterns are sensual and tactile, with painted elements varied in each piece. In Secret Garden, her work is almost like stained-glass, rich and deep. Be Still My Heart is more of a mosaic, with its image of an actual heart blossoming like a flower. And speaking of flowers, Heartbreaker makes muted blossoms grow around the image of a woman’s lingerie; the darker, more muted palette seems like an elegy for a femme fatale who has cast that role away. In and Out carries an autumnal color palette and reveals broken handcuffs, once again calling to mind the idea of a role or a relationship cast aside.

Leigh Salgado, Ballgown, 2021 Ballgown, with a golden background and a dress seemingly made of bubbles, appears to burst the fairy-tale-princess myth into something that doesn’t last, a temporary dream at best.

Leigh Salgado, Red, 2021 Launch Gallery,

ends November 13. -

Bennett Roberts

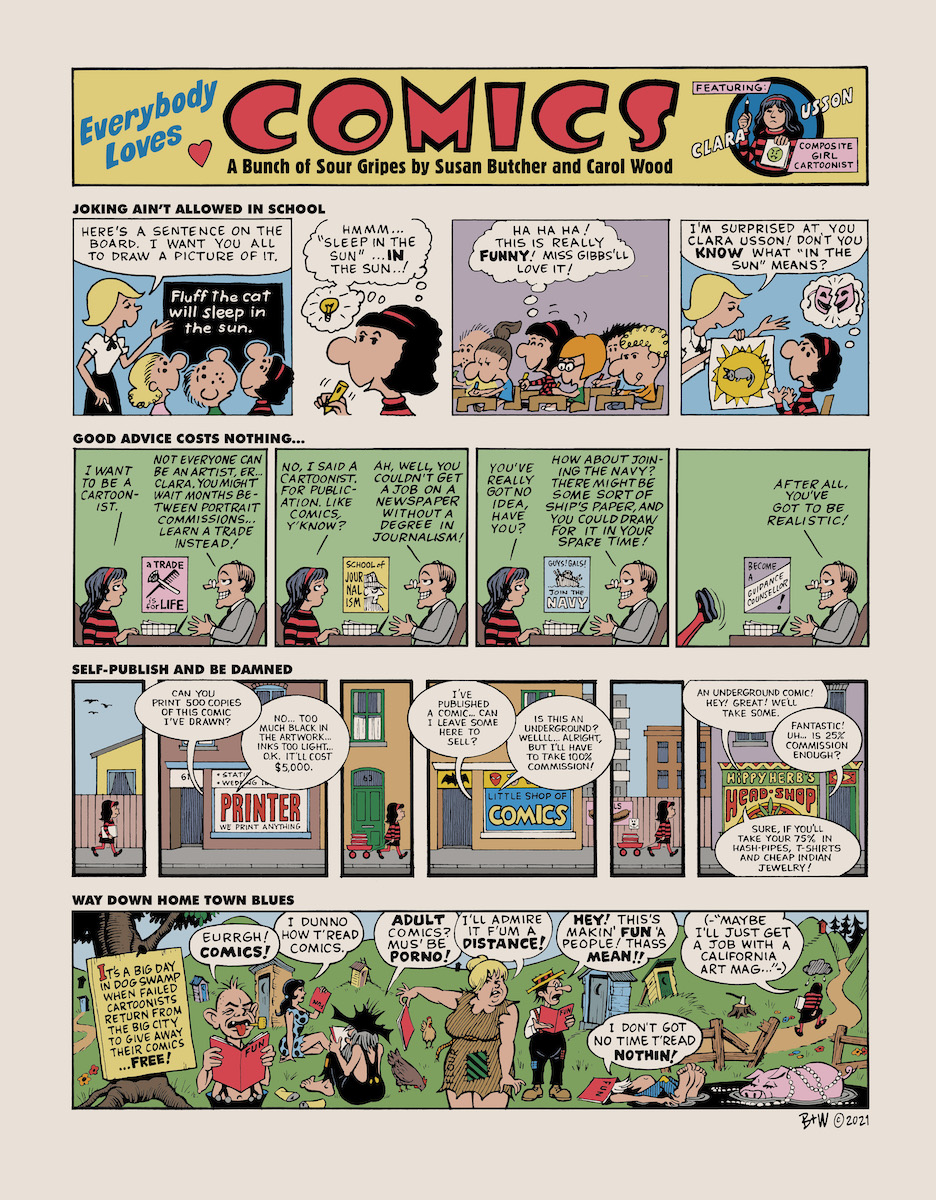

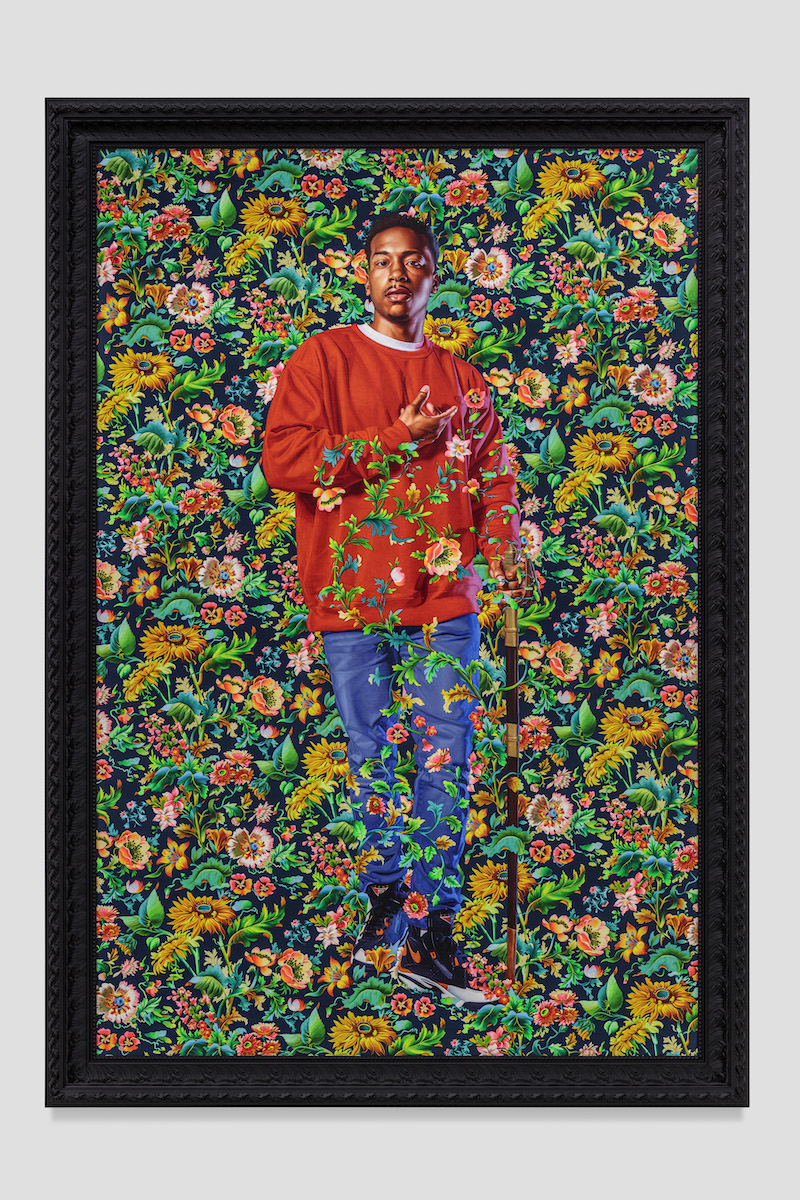

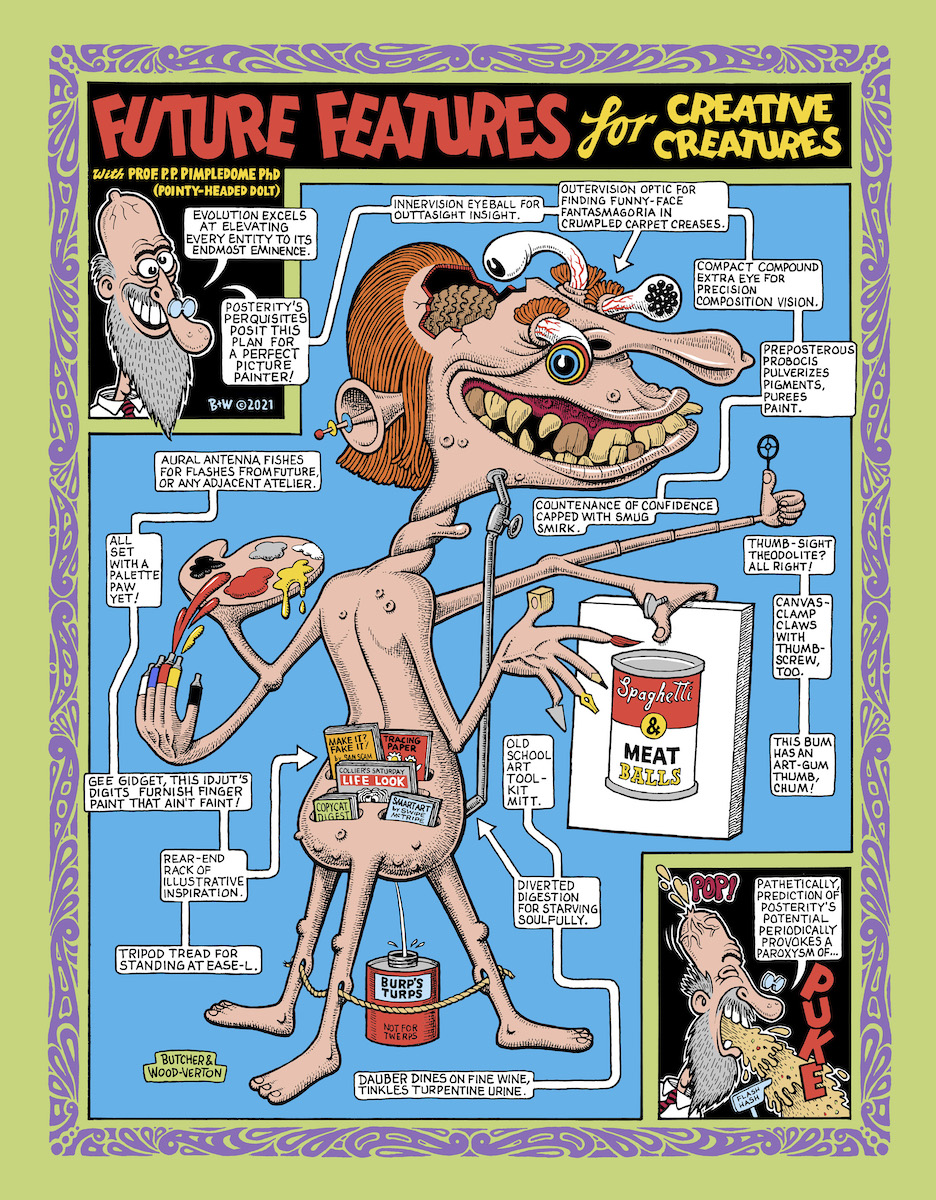

It’s About TimeBack in 2006, I approached Bennett Roberts at his gallery on Wilshire Boulevard with a bit of chagrin. The LA art dealer had always been nothing but nice, helpful and accommodating to me as a person and as an arts writer. So my heart was heavy when I had to break it to him—before he could read it in the latest edition of Artillery—that we had panned his Kehinde Wiley show.

Roberts, unflinching, seemed to be suppressing a grin. Was it because a review in Artillery had no significance to him, or was it his absolute confidence that Wiley was already untouchable? I chose to believe the latter. He graciously invited me in to linger at the show and told me not to hesitate to raise any questions. That made quite an impression on me as a journalist; I really respected his very adult manner.

Fifteen years later, a lone Kehinde Wiley painting hangs on an empty white gallery wall, surrounded by brown-paper–wrapped canvases awaiting installation at Roberts Projects. I assumed the unopened art was Wiley’s; Roberts informed me otherwise, stating it was Amoako Boafo’s next show—the Wiley was there for a client-viewing later in the day.

The irony did not escape me as we sat down in the main gallery for the second meeting of our interview. The first time was at the Los Feliz home that Roberts shares with his wife and business partner, Julie Roberts. That was nearly a year ago (that pesky pandemic kept delaying things), and it was now September, the start of the new fall art season. Julie, a full and equal partner in the gallery, was in New York at The Armory Show while hubby stayed behind to attend to their upcoming exhibition—there’s a long waiting list for Boafo’s work—“hundreds.” The African artist who has been showing with Roberts Projects since 2018 is super-hot right now; Roberts could not afford to be away that opening weekend.

Business is going well for the gallery. Many of its artists are in high demand, and artists that have stuck by Roberts over the years are now getting their due—current art star Betye Saar for one. Roberts is in high spirits and ready to begin the interview before I even get the recorder going. He kicks off by singing high praises for LA’s current recognition as an important art center—finally. “It’s always been a great center for artists.”He pauses before acknowledging—for galleries and collectors—“not always so great.”

In the past, Los Angeles was notorious for its inferior collector-base compared to New York. Roberts recounts the LA collectors of only a few decades ago; “If they’re going to spend 30 to 50 thousand dollars or a million dollars, they’re going to buy from New York. It gave them more confidence.” That is no longer the case.

Roberts emerged in the LA art scene amidst the ’80s art-world explosion, after returning home from college in Santa Barbara. He grew up in Brentwood, a wealthy neighborhood on LA’s west side, with a producer-writer father in the film and television industry. Roberts attended Windward, “a well-known private school,” he points out, where his best friend was Richard Heller—of the Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica. In the summer of 1986, Roberts and Heller picked up where they left off and started a gallery in Heller’s father’s garage. They called it Richard/Bennett Gallery.

Within a year, they were confident enough to move into a “real” space on La Cienega Boulevard near some of LA’s hottest galleries, like Rosamund Felsen, who was debuting the likes of Mike Kelley and Lari Pittman. Richard/Bennett proved to be no slouch either: they were the first to show Raymond Pettibon, and were responsible for introducing his work to Chief Curator Paul Schimmel—who in turn put Pettibon in the famed 1992 Geffen/MOCA show, “Helter Skelter.” Running the gallery was a struggle, Roberts admits, but somehow just when they didn’t think they could cover their rent, a miracle sale would happen, or a collector would buy a few Pettibons for $250 apiece to help them out. With measured success over five years, Roberts and Heller parted ways, both continuing their own successful careers as art dealers.

Kehinde Wiley, Yachinboaz Ben Yisrael II, 2021, oil on linen, 106.5 x 74.25 x 4.25 in. framed; courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California, photo by Joshua White RETAIN & MAINTAIN

According to Roberts, a central challenge in running a successful gallery is retaining your artists. Yes, Pettibon eventually moved on; his career skyrocketed after “Helter Skelter” and today he is represented by Regen Projects in LA and David Zwirner in New York—there’s always a bigger gallery, a better offer. Roberts concedes there’s a long list of artists who got snatched up after he invested in them. But that’s typical and expected. “It’s unavoidable,” he maintains.

Take Roberts Projects’ biggest artist, Kehinde Wiley—it is by no means the only gallery representing him. Things have changed drastically since the 1980s era, when galleries had exclusive partnerships with their artists. Roberts says he prefers the new system—a more polyamorous relationship, if you will. He concurs, “I like Kehinde showing with someone different in London, someone different in New York. I make less money and get less pieces, but those people have different collectors, different curators that are interested in that program. Artists are seen differently, depending on the program they are in.” Roberts thinks that artists showing with other galleries is not necessarily a bad thing. Another newer trend is for a gallery to have multiple spaces. Galleries don’t often want to surrender their artists to another gallery and take lower percentages (like Roberts did with Wiley). He notes, “It may actually be cheaper in the long run to have another space in New York to show that artist rather than giving the artist to another gallery.”

Roberts emphatically stresses that it’s all about retaining the talent you’ve developed. “The longer you retain it, it is perceived as important…,” he interrupts himself, “I use ‘perceive’ because everything is about time. Everything in the art world is about time. Everyone thinks it’s about popularity, success, money; it isn’t. It’s about how much time you can keep that person in play.”

Roberts believes that for an artist to have historical staying power, a cultural discussion needs to revolve around that artist and their work. Until that dialogue expands outside the art world it remains “an inside discussion.” In other words, that work will not make a wider impact, nor make it into the history books.

Kehinde Wiley’s oeuvre has crossed over to become part of a cultural discussion. Two factors play a part: his commissioned presidential portrait of President Obama and, most recently, his version of the famous Blue Boy portrait hanging at The Huntington (The Blue Boy is on loan to London’s National Gallery). Roberts Projects had a huge part in making that transaction happen. Those projects propelled Wiley into a wider cultural sphere, surpassing just the art world. Most likely, he will go down in history.

Amoako Boafo, Monstera Leaf Sleeves, 2021; oil and paper transfer on canvas, 77 x 76.5 in.; courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. BLACK ARTISTS MATTER

The Black Lives Matter movement filtered into the art world quickly; in fact, most would say much earlier than the mainstream cultural embrace. Today, if your gallery doesn’t represent Black and POC artists, or include much diversity, you might as well be showing cave paintings. Roberts had been representing Black artists long before most galleries caught up to speed. His gallery didn’t seem to get much credit for it, but he wasn’t looking for it either. The artist roster has always been inclusive, starting with Kehinde Wiley in 2002, Noah Davis in 2006, Betye Saar in 2010 and recent additions of African artists Boafo, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe and Wangari Mathenge.

The Black artist movement is thriving right now and Roberts Projects is right on target. Alongside Wiley, Noah Davis was a big hit for them. Davis, too, is engaged in that bigger historical discussion, as co-founder of The Underground Museum, an institution created to show museum-quality work in a Latino and Black LA neighborhood that was underserved in art exposure. Davis died of cancer in 2015, at the tragically early age of 32, but had left the Roberts & Tilton gallery in 2012 (Roberts’ former gallery with partners Julie, and Jack Tilton, who passed in 2017). All ties between Davis and Roberts & Tilton were severed by then, and David Zwirner obtained Davis’ estate in 2020. (Zwirner needs to hurry and check all those boxes).

Roberts isn’t upset about that, but more dismayed about the erasure of Roberts’ involvement in developing Davis from the beginning. “I helped sell pieces to fund The Underground Museum.” Roberts pauses with quiet exasperation. Zwirner produced a huge monograph on Davis with nary a mention of Roberts. “It was unbelievable to me how the art world loves to rewrite history and make it seem like only the winners write it. Not the ones that are up-and-coming, or the also-rans.” Roberts was key in putting Davis on the map circa 2007. Roberts & Tilton were participatining in an art fair when Don and Mera Rubell (serious art collectors and clients) stopped by their booth and inquired about a painting. Roberts recalls Mera demanding: Who is this great artist on the wall? “I said, ‘It’s a brand-new discovery of mine. I think it’s terrific, I think you should get something.’ They said, ‘You know what? We’re doing [a show called] ‘30 Americans.’ And he will be the final and youngest artist we include in the show.’ And I said, ‘Thank you very much.’”(Let that go down in history—you read it here first!)

Betye Saar, The Destiny of Latitude & Longitude, 2010, mixed media assemblage, 54 x 43 x 20.5 in., Baltimore Museum of Art; purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California ONE PERCENTERS

Let’s face it, the art world is a rich man’s game now, and with the world’s wealth concentrated among the one percent, it’s a small playing field. “It is the game you play after all the other games you’ve played,” Roberts explains, “It is the final frontier.” He goes on, “It is the place that once you’ve made whatever fortune you’ve made and you have what everyone else has… you can differentiate yourself from all the other billionaires by collecting things that are not only great but are truly something that will enhance how you see your own position in things.” Pausing, Roberts surmises, “It’s a game of fortune.”

One-percenters have needs too. “When you’re that big, the richest people want to buy from you, because they feel secure buying from you,” Roberts says. That’s why mega-galleries like Gagosian can and do exist. At last count Gagosian had 16 galleries worldwide. In today’s global market, having art galleries around the world seems more shrewd than extravagant. Another factor, Roberts explains, “All of those businesses have a very, very vibrant secondary market—that’s truly where all the money is.” At that level, the competition is with the auction houses; they don’t care about other galleries at that point. Roberts acknowledges he’s not in that league—and is relieved not to be.

Roberts refers to what’s happening right now in the art world as a “sea change.” His and Julie’s gallery is rolling with the new system, and in fact thriving. “I don’t think that I even sell things anymore—I think people buy things from me,” Roberts says reflectively. “Zero pressure. I want the experience to be as clean and as enjoyable as possible.”

I’ve watched Roberts’ gallery remain fresh, relevant, edgy—top-notch for over 30 years. With Betye Saar’s soaring career, the recent Wiley accomplishments, and rising star Amoako Boafo on board, it is undeniably riding the wave.

Unsurprisingly, Roberts announced at the end of our interview that they will be moving from their space to La Brea Avenue. The new gallery will be three times larger than their Culver City venue. And no, Roberts Projects will not be adding another gallery; they just need a bigger space for displaying larger works and a nice showing room for their clients—where they can have an enjoyable experience considering the lone Kehinde Wiley spotlighted on the wall.

-

More Fireworks for MOCA

Art BriefOne of the most memorable events at MOCA occurred when Chinese-American artist Cai Guo-Qiang exploded gunpowder from an exterior wall of the Geffen Contemporary just after sunset, setting off blinding and spectacular explosions before a huge crowd unprepared for such fire and fury. Immediately after that, the startled guests staggered inside to view Cai’s exhibition of gunpowder residue artworks. Cai should reprise that 2012 show as a ritual demolition of a museum which has gone completely off the rails in the last 10 years with a shocking series of revolving-door hirings and firings of directors and curators.

The latest MOCA debacle started with the announcement this May that short-tenured museum director Klaus Biesenbach would be demoted to “artistic director” while a search was made for a new executive director. Biesenbach was a sub-par administrator who failed to implement the museum’s diversity initiatives, contributing to the departure of highly regarded senior curator Mia Locks and the resignation of the human resources chief. Biesenbach—a known talent as a curator—had a history of success in his hometown of Berlin and at MoMA PS1 in New York, but was ill-suited for the challenges faced by the arcane and sprawling world of art in California.

MOCA announced the hiring of the new museum director, Johanna Burton, in early September. Biesenbach got his revenge several days later by announcing a return to Germany as head of Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. Biesenbach was the wrong person at the wrong time for MOCA, and faced unforeseen challenges when the museum suffered a prolonged COVID shutdown and resulting staff cuts.

Burton is the former director of the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University and will be MOCA’s first female director. After Biesenbach’s departure, the museum announced that no artistic director would replace him and that Burton would be the sole executive in charge. Burton needs to re-invent MOCA, develop a clear, coherent vision for the museum’s core mission and bring in a strong curatorial team.

Arguably, the two most important exhibitions in MOCA’s history were 1992’s “Helter Skelter” and 2011’s “Under the Big Black Sun,” both of them revealing the rot beneath the perpetual sunshine of the Golden State. It’s no coincidence that those shows were organized by legendary MOCA Chief Curator Paul Schimmel, who was steeped in California art history.

Installation view of “Under The Big Black Sun,” 2011 MOCA’s longtime senior curator, Bennett Simpson, is known for a number of successful shows, including a Mike Kelley retrospective and a memorable “Blues for Smoke” exhibition, but MOCA needs additional curators who are experts in contemporary California art.

Most of MOCA’s problems stem from a lack of clarity on just what the museum’s core mission is. A brief “Mission Statement” appears on its website with such inanities as: “We are a museum; we are contemporary; we care.” Unfortunately, the mission for MOCA since 2008 has been focused on survival due to near insolvency. It is only in the last few years that fiscal stability has been achieved with a large increase in MOCA’s endowment under the leadership of board chair Maria Seferian.

Since the 2015 opening of The Broad museum, directly across Grand Avenue from MOCA, the new kid on the block has presented a huge challenge. Endowed by a billionaire, the late Eli Broad, its blue-chip collection contains more marquee masterworks than MOCA’s. The Broad offered free admission, causing a surge in attendance that outpaced MOCA; in response, MOCA abolished its own admission charge.

MOCA needs to differentiate itself from The Broad, which has a solid foundation of works by contemporary New York and European artists. The Broad is noticeably weak in its holdings of California artists (with the exception of Ruscha and Baldessari). Fortunately, MOCA has an encyclopedic inventory of works by California artists. MOCA should focus its mission on being the primary museum for contemporary California art. Its exhibitions should be California-centric. Since The Broad leans to Europe, MOCA can counter-program with more shows of contemporary Asian art.

MOCA must also join the post-BLM initiative of artistic institutions seeking to re-balance collections with acquisitions from Black, Latino, Asian, LGBTQ and female artists. It’s off to a good start—dozens of recent MOCA acquisitions have been made with diversity in mind, including works by Lauren Halsey and Rafa Esparza.

Exhibitions also need to focus on avant-garde artists and art movements. The Broad has been attracting some solid shows, including “Soul of a Nation” and a Jasper Johns exhibition, although they have been primarily borrowed, not home-curated. It’s likely that The Broad will continue to rely on mounting conservative exhibitions. MOCA needs to be the un-Broad and provide some explosive shows once again.