Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: contemporary

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Loft at Liz’s

Group Exhibition “Diverted Destruction 15: The Demolition Edition”Co-curated by Liz Gordon (of Loft at Liz’s) and Monique Birault, the 15th iteration of Gordon’s ecologically driven “Diverted Destruction” is both exciting, and more visually spare than past exhibitions. Rather than filling the main gallery space with smaller pieces created from recycled materials, this time around the artists confront waste created from construction and demolition materials.

Using concrete, asphalt, wood, drywall, brick, clay tiles, shingles, and metal, artists including Anna Stump, Sonja Schenk, Ben Novak, Joseph Salerno and Howard Lowenthal work in a variety of approaches to this material, while in the gallery’s alcove, a robust and ever-changing collection of materials are available for giveaways, with mixed media workshops encouraging their use.

Schenk’s piece is a suspended, monumental work evoking memories of the 2001: A Space Odyssey monolith had it cracked into pieces and turned horizontally with her Solid, Void, Other (Red Shift) made from polystyrene, glass, and acrylic paint to float like a feather of detritus.

Anna Stump detail Stump’s approach is playful: her Mojaveland Jackrabbit Hole recreates a Par 3 hole from her artist-designed miniature golf course and art center in 29 Palms. Made of broken concrete bricks originally used to build 1950s-era desert homes, the mobile mini-golf puts these found commodities to cleverly visualized delightful use. Also on exhibit: a series of mix-and-match painted concrete bricks, some delightfully depicting exquisite jackrabbits.

Novak works in welded metal and plastic found objects, creating what he terms “environmental work” dedicated to sustainability. He uses vintage tools in a numbered Weisman Tool Series, and found metal objects to create fascinating, elaborate mini towers in his Pandemic Year 2 Series.

Howard Lowenthal detail Lowenthal, a.k.a. SMTDLR, shapes irreverently fantastical mixed media in his Terra Inifrma, crafted from aerosol, acrylic, and sculptural debris. Salerno’s work feels more substantial, using industrial materials with minimal touches of color, such as oriental pink marble in his Shelter the Weak, and a softly glowing beige travertine along with rebar and stone for his in a landscape. While the materials are primarily industrial, these works seem to inhabit an imagined natural geology, like new sedimentary rock formations.

The exhibition is on display through September 20th at Loft at Liz’s on La Brea, mid-city.

-

OUTSIDE LA: Cornelia Parker at Tate Britain

Small Island EnergyCornelia Parker’s landmark retrospective at Tate Britain journeys through her multimedia work to narrate a country willingly stuck in small-island-energy. Parker (b.1956) examines objects by considering how they change when their associated value is disrupted, destroyed or dismantled. The juxtaposition between large scale installation and Parker’s accompanying text, dissecting her process and interest, creates an exhibit that is subtly scathing of the geographical entity it is taking place in.

The exhibition begins with Thirty Pieces of Silver (2015), a sculpture of over a thousand pieces of low hanging flattened silver, suspended from the ceiling and gathered in plate-like rounds. It’s a visually pleasing entryway into Parker’s installation work.

The second gallery delves into Parker’s political intrigue with two neighboring sculptures Embryo Firearms (1995) and Embryo Money (1996). Her partnering text tells us the firearm is a cast metal sculpture of a gun from the first step in its manufacturing process that she acquired from visiting a factory in Hartford, Connecticut. The second piece is a metal disc from the Royal Mint, Pontyclubn, Wales. A coin before its currency, value and power are asserted for mass circulation via the addition of someone’s face. Parker’s words, like object poems, make the work accessible whilst ensuring her intrigue and intentions are not misconstrued by the viewer.

Anne-Katrin Purkiss, Cornelia Parker, studio, London, 2013. © Anne-Katrin Purkiss. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022. The screening room plays a selection of Cornelia Parker’s film: a Palestinian father and son weave crowns made from thorns in Bethlehem, machinery makes and throws out poppies at a factory for the UK’s remembrance day, a trio of videos on UK politics includes Parker’s submission as the official artist for the general election in 2017. This depicts a dizzying display of the fast pace chaos of the 90 day election cycle and British tabloids. This is followed by a film of halloween celebrations in New York, a week before the election of Trump, partnered with a video of Trump supporters outside Trump Tower in the piece American Gothic (2017).

Cornelia Parker, Perpetual Canon, 2004. Collection of Contemporary Art Fundación “la Caixa”, Barcelona © Cornelia Parker There’s a disturbing lack of sound that carries through much of the later exhibit. It begins with the echoing noise of the machinery in an empty warehouse in the video of the poppy factory in Richmond. This leads into the installation War Room (2015) a huge tent constructed of suspended strips of material that poppies are cast out of. In Perpetual Canon (2004), marching band instruments are flattened and hung in a round, the orchestral noise instead comes from the many shadows of the instruments on the walls.

Cornelia Parker, War Room, 2015. Image © the Whitworth, The University of Manchester. Photography by Michael Pollard The silent presence felt is also a result of the tension created from the spaces Parker visits in order to make her work: from visiting gun making factories, border control in Texas, to a poppy making factory. A photograph of clouds was taken with a camera Parker borrowed from the Imperial War Museum that belonged to Rudol Hoess, the commandant of Auschwitz. Parker describes looking through the same lens as a mass murderer; the resulting photograph is uneasy and sinister. Her work exposes the most unsettling parts of society, and at times it feels at the expense of herself with the heavy process underlying the artwork.

Cornelia Parker, Avoided Object. Photographs taken on the sky above the Imperial War Museum with the camera that belonged to Hoess, commandant of Auschwitz, 1999. Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London. © Cornelia Parker The last piece Island (2022) is a glass garden shed. A bulb inside slowly lights up and dims out like breaths. White lines are painted on the glass using chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover, a quintessential English landmark. Dover is also a politicized transportation entrypoint and departure for the UK, the use of this chalk alludes to the country’s obsessive anti-immigration policies. The white lines keep the light in and the heat away, as Parker would do to her shed as a child to protect tomatoes from the summer heat. The covered shed signifies the UK looking inwards, alone, a small island. Parker is addressing a post-Brexit England not wanting to be part of Europe; a prevalent topic amongst artists and art institutions attempting to evolve and reimagine understandings of Europeanness as the UK chooses a more distant relationship with the continent.

Cornelia Parker at Tate Britain is an immersive critique of the frequent devastation humanity causes, through her intrigue at seemingly arbitrary objects. As the exhibition closes in on the UK with Island, the overarching message that lingers is that not only is small island energy in the UK detrimental and sickly, but nonsensical.

The exhibition runs until October 16th.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Lev Rukhin

East 26 ProjectsRussian exile Lev Rukhin creates grand works of realism tinged with just enough peculiarity to suggest doubt. They are dreamlike—much of the imagery is suspended in a nimbus—and implies both memory and trickery. This device is quite intentional; the exhibition is titled Dreamscapes.

Pressed together in scores of photographic tiles, these large-scale images are a peripatetic narrative echoing both his contemporary travels and his fragmented memories, of things firmly recollected and those hazily recalled. In Hero’s Journey, 72” x 96” (all works 2020), sits a Pittsburgh factory devoid of workers, a skeletal remnant of the former smoke belching Eastern powerhouse so fearsome that it had been referred to as “Hell with the lid taken off.” In the triptych, Homage to David Hockney, 72” x 144”, Rukhin’s silhouette can be seen illuminating a tall spiny yucca as waning sunlight rims the horizon. The artist is visible in many of the works as if assuming the role of tour guide and eager to reveal the singular beauty of the unvarnished. His comparable yet much smaller Dunes places a similarly solitary tree in a much emptier landscape, isolated with an expectant or communicating human figure; the towering Brooklyn Chimney, 48” x 48”, becomes an obelisk worthy of homage as it watches over the sprawling boroughs.

Lev Rukhin, HERO’S JOURNEY, 2020. Laminated archival dye-sublimation photographs, layered, cropped into circles, hand-mounted onto aluminum honeycomb substrate. The gallery’s darkened rough-hewn floor lends a melancholy and contemplative aura to the works that are already doleful. Masonic Lodge, one of the smallest works in the exhibition, is a genuine haunter, suggestive not only of ghosts but advantages pressed, opportunities denied, and stratagems contrived. For an artist expelled from a homeland where subterfuge was a national obsession the ghosts of the past and the apprehension of the future are fraternal twins. Umbrella Man—part of his Los Angeles series of diverse figures—walks swiftly by in his shimmering suit, a wary eye ever cast behind him, his wide umbrella disguising his shadow.

Lev Rukhin: Dreamscapes

East 26 Projects

June 11-August 7

-

OUTSIDE LA: Documenta 15

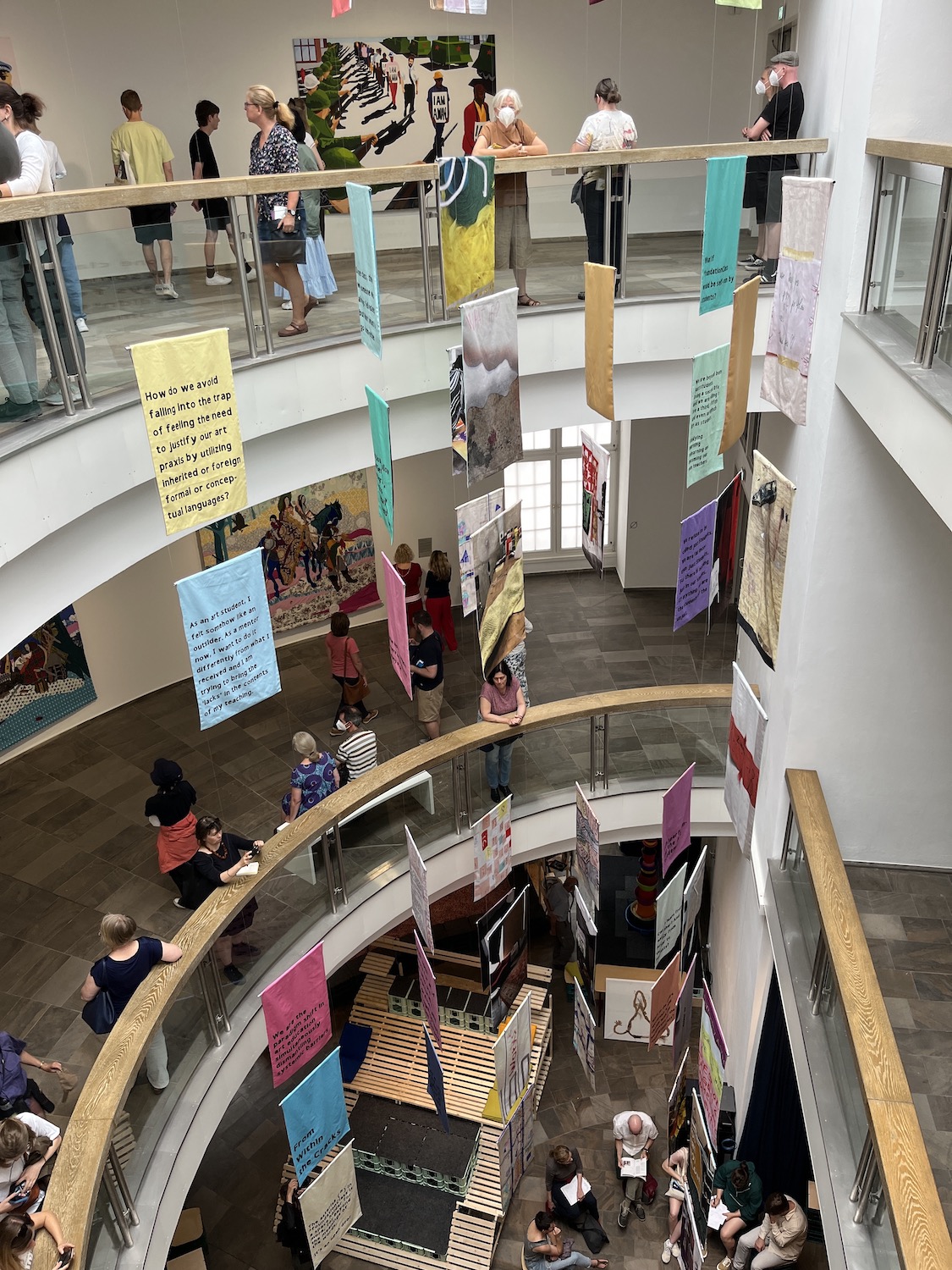

Kassel, GermanyThe first iteration of Documenta, curated by Arnold Bode, took place in 1955. Since then, every five years for 100 days, Documenta occupies the city of Kassel, Germany. More often than not, it is an international showcase of current trends and ideas in contemporary art. A curator or curatorial team is chosen and given carte blanche to put together the exhibition. During the 100 days, thousands of visitors descend upon Kassel to see hundreds of exhibits presented in venues located all over the city. For 2022, the collective Ruangrupa, based in Jakarta, Indonesia was chosen as curators. This is the first time that artists have had curatorial control of Documenta and their exhibition has a different tone and attitude than any of the others. While Ruangrupa’s work (in the form of a radio station) was exhibited in Documenta 14, it came as a surprise that they were invited to organize Documenta 15. Documenta 15 opened amid controversy: accusations of antisemitism and the resignation of the director general of Documenta have continued to plague the exhibit.

Ruangrupa has based Documenta 15 upon the values and ideas of lumbung — principles of collectivity— and one of the aims of their exhibition is “to create a globally oriented, collaborative and interdisciplinary art and culture platform that will remain effective beyond the 100 days.” Another focus of Documenta 15 is accessibility and sustainability. As the curators state, “The theme of sustainability is reflected throughout all aspects of the exhibition planning and implementation.” Documenta 15 features over thirty venues and for the first time in Documenta’s history, the ticket to the exhibition provides free access to public transportation. Other implementations of sustainability are the myriad gardens created by artists and collectives invited to participate in the exhibition. Visitors to Documenta 15 expecting to be wowed by paintings and sculptures might be disappointed as Ruangrupa’s curation does not celebrate aesthetics, but rather promotes discussion and community. It is interesting to think about how works made by artist/activist collectives and notions of community translate into Art. In fact, many of the installations are text based, instructive, didactic and not always visually compelling. While Documenta is somewhat of an urban experience, Ruangrupainvited collectives that prepare food, create gardens, as well as spaces to gather, converse and perform in parks and neighborhoods across the city. Sadly, during my visit because of a Covid outbreak, all gatherings, tours, films and lectures were canceled.

Black Quantum Futurism at Documenta 15, 2022 There are many trajectories through the numerous Documenta 15 venues. Most people begin at ruruHaus which serves as the welcome and information center. Here one can get a ticket, maps, a snack, use the restrooms, peruse the bookshop and view an informative timeline that outlines the complications (Covid 19, supply chain delays, visa and travel issues, heat waves, the war in the Ukraine) that hampered the production of the exhibition. In most years, the main venues for the exhibit are the Documenta Halle and the Fridericianum located in the center of the town, as well as the large grounds of Karlsaue Park. Artworks are also often installed in underpasses, at the train stations and in Kassel’s art and historical museums, as well as in nontraditional locations and buildings secured for the duration of the exhibition.

With more than 1500 artists/exhibits it is impossible to quantify the experience. What follows is what resonated during my four days in Kassel.

For those who arrive at the Kassel KulturBanhof, they can visit a small installation by Jimmy Durham and A Stick in the Forest, a collective formed after the artist’s death. Outside the station are Dan Perjovschi‘s drawings on painted white rectangles scattered across the pavement of the plaza. These poignant, cartoony, doodle-like drawings offer commentary on art and current events. Perjovschi’s work also covers the columns outside the entrance to the Fridericianum. Toward the edge of town is the Hallenbad Ost (an old pool house that was empty for many years and recently rebuilt) where the Indonesian collective Taring Padi has installed a twenty-year survey of their work. Outside the building are hundreds of life-size painted cardboard cutouts (these are also presented inside and in front of many of the other locations) depicting various characters proclaiming different social, political and cultural issues. Nearby was St. Kunigundis, a Roman Catholic Church built in 1927 where members of the Hatian groups Atis Rezostans | Ghetto Biennale presented works that encompassed many media. Hübner Areal, (a recently vacant factory that used to build parts for buses, trains and tanks) is a huge warehouse-like space that houses works by many different artists and collectives. The installation has the feel of a funky art fair where there are no dividing walls to separate the projects. Included here are spaces for discussions and performances, as well as works that span the walls, floors and ceiling. The collective BOLOHO turned the factory cafeteria into a Cantonese-style cafe open to all. In another multi-floor, multi-artist building Hafen-strasse 76, were works by Nino Bulling (hand-painted drawings on silk suspended from the ceiling that expanded on their book abfackln) and Fehras Publishing Practices, a queer collective based in Berlin that investigates Arab-language publishing, has created a photo-narrative spanning more than 100 panels that focuses on the feminist women behind the Afro-Asian Solidarity Movement.

Taring Padi at Documenta 15, 2022 Along the Fulda river are works by Black Quantum Futurism and the Nha San Collective who erected a bench on the bridge, as well as Nguyen Trinh Thi‘s projection / sound work housed within the Rondell, originally a defense tower built in 1523 that now serves as an exhibition space. Nguyen’s evocative and peaceful piece consists of projected silhouettes of plants complemented by a haunting soundtrack. The work is based on the autobiographical novel by Bui Ngoc Tan, Tale Told in the year 2000, about life in detention camps in Vietnam in the 1960 and 70s. Other works in situ include: The Nest Collective who have created a walk in sculpture (that houses a video projection) made from large parcels of industrial and plastic waste, a giant compost heap, an active green house garden, as well as a sculptural tower that serves as a his/her public outhouse, a contribution by Mas Arte Mas Accion.

Fridericianum interior, Documenta 15, 2022 Inside the Fridericianum, it is a bit of a chaotic mish-mash. Upon entry, viewers are greeted by Dan Perjovschi’s full-scale wall-work that annotates and comments upon the Documenta 15 funders. To the left, the space is devoted to RURUKIDS, which is in essence, Documenta daycare (closed due to Covid concerns during my visit): a space where parents and children can learn and play. Also located within the Fridericianum (as well as other venues) are quiet rooms where people can take a break from stimulation, sit in silence and stare at unadorned walls in a darkened space. On the top floor are pieces by Project Art Works, a group from Great Britain that works with people with learning disabilities, or who are neurodivergent, to explore their creative potential. Displays of films and ephemera from The Black Archives, the Asian Art Archive and the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algerie are full-fledged historical exhibitions nested amongst works by individuals and other collectives. One of the few painters given a solo presentation is the Aboriginal artist and activist Richard Bell. Bell’s flatly rendered representational paintings depict protests and conflicts. He states that his works explore ” the complex artistic and political problems of Western, colonial and Indigenous art production.” Also in the Fridericianum are films by artists from the collective Sada [regroup] who came together in Baghdad from 2010-2015. This included a compelling short film Journey Inside a City by Sarah Munaf, about the after effects on Iraqi artists from the U.S. war to remove Saddam Hussein.

Adjacent to the Fridericianum is Documenta Hall and the Museum of Natural History Ottoneum. The entrance to Documenta Hall has been transformed by Nairobi based, Wajukuu Art Project into a tunnel made of corrugated metal that also covers many of the interior walls and windows, setting a tone that celebrates makeshift architecture. The corrugated metal reappears on the lower level of the Documenta Hall where one finds not only a functioning print shop that produces books and posters for the exhibit, but also a skateboard ramp and performance stage orchestrated by Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture, a collective from Thailand. The lower level is an active, dynamic space where viewers can hang out and interact.

Richard Bell at Documenta 15, 2022 Among my favorite artworks at Documenta 15 are a two channel video projection located in the Ottoneum by Korea’s Ikkibawikrrr collective. This subtle and compelling 12 minute loop titled, Tropics Story, pictures war remnants at locations formally occupied by the Japanese Empire that include images of “overgrown airstrips, abandoned cave fortifications and burial grounds that hint at how war is metabolized by nature.” In the Grimmwelt Kassel, a museum showcasing the works of the Brothers Grimm, is a multi-media installation by Jarkata’s Agus Nur Amal who creates his own fairy-tales and story telling session on the top floor of the museum. Perhaps the most memorable space and installation was Erick Beltran‘s Manifold at the Museum for Sepulchral Culture— a space that collects and showcases works about the global rituals around death and dying. For Manifold, Beltran has created a series of hanging banners and wall mounted murals filled with texts and diagrams that explore the peoples’ conception of ‘images of power.’ This complex installation also includes sculptures and a video where these images of power are animated to illustrate the relationships between them.

The takeaway from Documenta 15 is that art can’t be separated from life. Much of what is on view is didactic — with prescribed political agendas, about social issues and made by collectives rather than by individuals— hard to digest and overwhelming to experience all at once. Yet, Documenta lasts 100 days and during this time, the gardens will grow, people will gather and the spaces and the exhibits will change. Those who can spend ample time investigating the myriad notions of collectivity will come away enriched. Those only looking for visual pleasure may come away disappointed.

Documenta 15

June 18 – September 25, 2022

Kassel, Germany

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Robert G. Achtel

Marshall GalleryThe City of Namara is a fictitious place created by Robert G. Achtel. In the photographs that define this curious and digitally fabricated location, Achtel presents Namara as a place devoid of people and filled with modernist architecture. Each building is shot straight-on and fills the frame. These evocative and precisely positioned structures are created by digitally compositing thousands of photographs of buildings, signage and the landscape, as well as fragments of sky and road that Achtel captured during visits to Nevada, Florida and California. Because they are digital composites, however seamless they might be, the works call into question the notion of photographic veracity. While Achtel begins with “real” physical forms, he changes the colors, proportions and relationships between the elements by using software, such as Photoshop, to create a heightened sense of place.

The Gateway (all works 2020) depicts the facade of a liquor store called Liquor Swamp. The scripted letters of the word liquor— white lines surrounded by black— are installed above diamond-shaped plaques with the letters S-W-A-M-P on a striated dark green facade of a midcentury modern building that has a Jetsons essence. Bisecting the building is a tall light pole supporting a sign that states, “No Parking: Drive Thru Only.” However, there is no visible drive-thru. Stone walls depicted in shadow make up the lower portion and are positioned on either side of the glass entrance. The building is set in a vast empty landscape with a few palm trees blowing in an invisible breeze. Telephone wires and the top of light fixtures provide a resting place for groups of birds that may or may not have been in the “original” photographs.

Robert G. Achtel, Jealousy, LightJet chromogenic print, 2020 In Jealousy, Achtel presents a stark white facade with nine tall recessed spaces, each casting slightly different sized shadows consistent with their positions in relation to the sun. The black block letters across the facade of the building announce “The Modern Gentleman” while in the window below, there appears a neon sign stating “Nudes 24/7.” As in The Gateway, the setting is devoid of life (except for occasional birds) and the landscape is a barren strip of road in a desert climate. To the left and just behind the central structure is a tall skyscraper jutting into the sky like a minimalist sculpture. To the right is another Jetsons styled modernist building with spiky yellow supports. At one time, this might have been a carwash or body shop, but in Achtel’s image the sign now reads “B-O-Y.”

Though each building is unique, Achtel’s process becomes a bit formulaic. In most photographs he sets the main structure against a distant landscape with palm trees and birds, as well as other modernist buildings placed at the edges of the image to emphasize a vanishing perspective. The buildings in Achtel’s city have specific functions — be it to entertain or heal— and Achtel reinforces this through the narrative implied by reading across the different fragments of signage. The facade of The Fix is a geometric design featuring bright green and blue interlocking diamond shapes. The patterned facade has nothing to do with the building’s function— it is a “drug” store called “World of Drugs” that advertises it as “Doc’s Choice.” Achtel includes a windowless building in the mid-ground called “Relapse” creating an ironic contrast. Relapse, replace, revive are all words easily associated with Achtel’s project. Many of the buildings photographed were once dilapidated, abandoned structures from bygone eras that Achtel has resurrected by compositing and then transforming myriad details from the originals.

Robert G. Achtel, The Fix, LightJet chromogenic print, 2020 What is most striking about Achtel’s images is the Bechers-like straight-on presentation of these fabricated facades. Though different, they exist in the same space, set back from the white or yellow striped road surrounded by blue sky. Achtel purposely creates over-determined spaces that are reminders of both past and present. The images allude to a dystopia. Is this dream city heaven or hell? The facades in The City of Namara with their modern enhancements are drawn from the landscape discussed in Learning from Las Vegas and reference 1950s architecture found in both Las Vegas and Miami. Achtel imbues his city with texts that speak to loss, love and dependence, while simultaneously celebrating the visual power of “Modernist” architecture.

Robert G. Achtel

The City of Namara

Marshall Gallery

July 9 – August 20, 2022

-

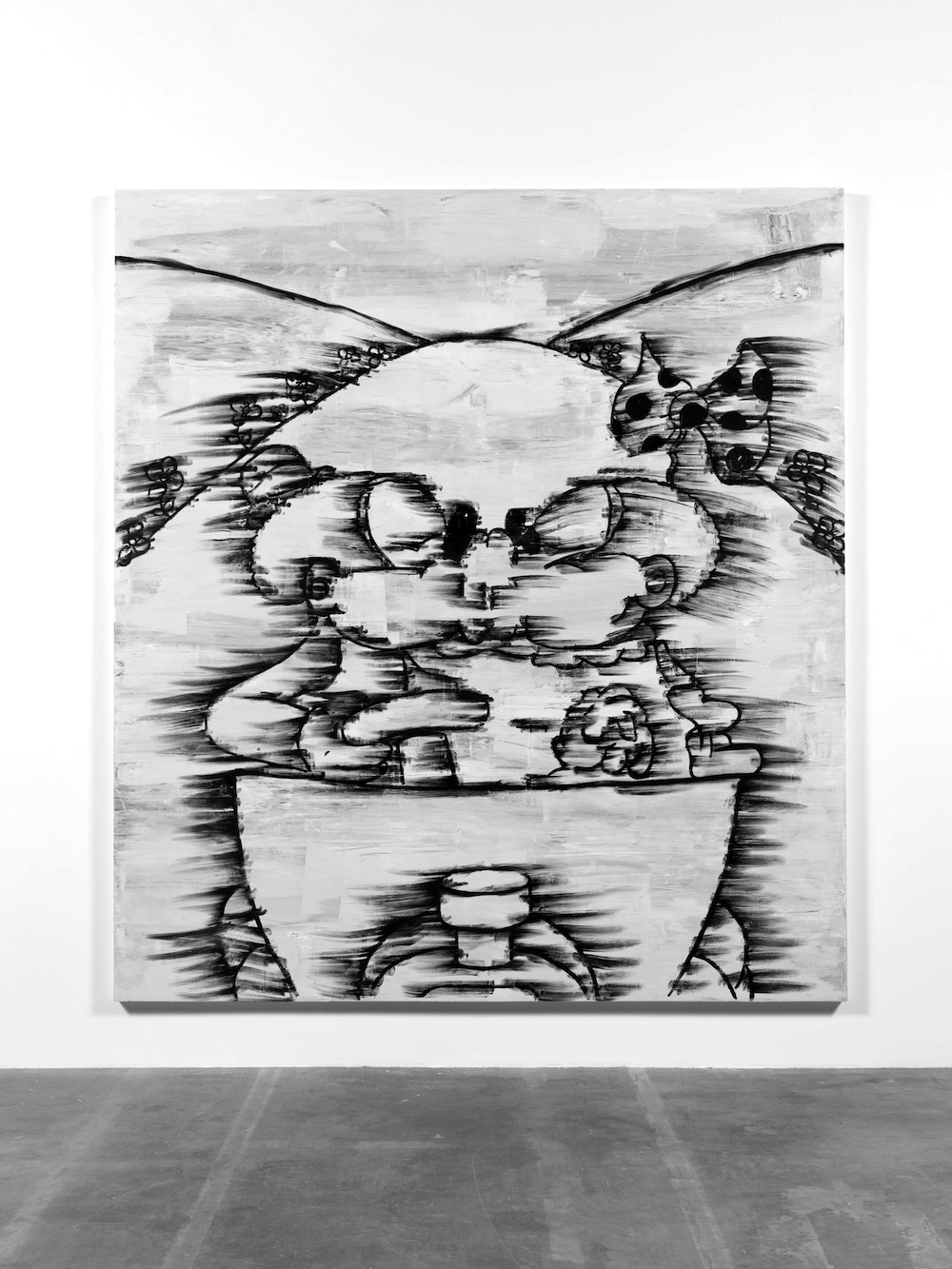

Bring the Pain

Gary Simmons at Hauser & WirthThe progress of his career has been a methodical march; carefully scripted, stubbornly stage-managed, and precisely choreographed—each subsequent exhibition enhancing the shudder of an already disconcerting thrum. The result of such a steady and painstaking pace has delivered an exhibition catalog worthy of MacArthur, yet his current exhibition is no laurel-chasing spectacle, it is a personally brazen and bitter step forward. Not satisfied to merely convey pathos, or defy hoary convention by shouting Macbeth! backstage, the artist is concerned with far more pressing matters. Gary Simmons is here to bring the pain.

Comedic, vulgar and unsettling, these apparent cartoons appear buoyant and frivolous. One might associate his imagery with graffiti (one would be wrong) or the vacuous fluff committed by Banksy (another misapprehension despite its uncanny fluence). Yet despite their varied black and white backgrounds, with wittily minimal accents of color—these characters force-feed the viewer mouthfuls of chalk dust. The fresh canvases on the wall are large (all 2020–21), the wall paintings larger yet, but the characters spit a comical bile, an intentionally acidic hocker in the eye of the beholder. These are ghost paintings, with characters that continue to haunt. They are dead and yet they live: in our bitter racist politics, our unequally funded schools, our trigger-happy policing, and freelance “white replacement” spree killers. Lynch Frog, features a character haplessly hanging, a peril no doubt brought on by his own darned foolishness. 88 Fingers Fats is so eager to entertain that he spirals himself into tar and turpentine. The paintings have the patina of the ancient but maintain an ever-potent bile, pantomimes that so tickle the funny bone of the secret cracker that the Warner Brothers’ Censored Eleven have risen from the grave and are once again enjoying distribution. These cartoons—a vile hoot for the unreconstructed—feature Coal Black and the Sebben Dwarves, where the mean old queen is nothing but impossible bosom, saucer eyes and face enveloping lips; Jungle Jitters, with a plump googly-eyed native whose nose ring is so expansive it does double duty as a jump rope; The Isle of Pingo Pongo, bone-coifed natives with lower jaws so extensive they serve as dinner plates; finishing with Goldilocks and the Jivin’ Bears, where a black wolf in grandma drag is chased up the chandelier by a telegram porter who pulls a gat and speaks in the voice of Jack Benny’s Rochester. Compared to the more egregiously bigoted imagery contained within, the titles and show descriptions seem downright elegant.

88 Fingers Fats, 2022, paint and chalk on wall, 144 x 657 in.; © Gary Simmons, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo by Jeff McLane. In a long career that has paced steadily toward a potent display of Black visibility through a rendering of its absence, Simmons has employed minimal tools to create elemental imagery. His 2010 exhibition titled “Black Marquee” featured sparse text on blank walls at Anthony Meier gallery in New York, a haunting contrast to the space’s renaissance revival interior. Rooms and corridors were emptied, leaving only the white arches and columns contrasting the near matte black walls. Streaked upwards and downwards the nominal white lettering described Blaxploitation films, creating an elegant accompaniment of X-ray reversal to Marcel Broothaers’ La Salle Blanche (1975).

Star Chaser, another of the sweeping paintings, is a tapestry of black—of eager hope tempered by bitter disappointment. His vast rendering of night is full of stars but all of them seem to be dying, not shooting. It is a stargazing portrait of embittered aspiration, the Pecola Breedlove knotted fitfully inside us, imbibing exterior resentment, and believing it porridge. It echoes in sentiment the artist’s Balcony Seating Only (2017), his polished floor reflections at Regen Projects, where segregated cinema reveals its aspirational dead end by the stairway to the Colored section, a steep and unsteady climb leading nowhere. Jittery lovers enact a romantic ritual in the 44-foot chalkboard fit of erasure, Lindy Hop. He presents a posy; her bowed hair reacts. They don’t yet know that this will be their high point, that ever after will reek of torment. Their youth is a buoyant ignorance and hard lessons are on the horizon. As in his Fade to Black (2017) at the California African American Museum, hopeful fantasy is again tempered by heartbreak in the race films Souls of Sin and Murder on Lenox Avenue. Cinema, a variety to which the Simmons imagery belongs, is a global language, and his figures are richly illustrated and quiveringly alive in the grandest of the rooms in the Hauser & Wirth depot; Lindy Hop, Star Chaser, and 88 Fingers Fats dominate the show as if in an arena. They silently overwhelm.

Splish Splash, 2021, oil and cold wax on canvas, 84 x 108 in.; © Gary Simmons, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo by Jeff McLane. The circuitous walk-through ends at the gallery’s garage door exit; it is more than suggestively the end of the road. In this final work, a subtler and damnably haunting installation, fairly spits its defiant title, You Can Paint Over Me But I’ll Still Be Here, which could address both itself as well as the hung canvases and wall paintings previously viewed, of no longer living yet never dying stereotypes. In this purposely less elegant expanse, the artist has suggested a school lunchroom. Its dining tables, however, are not laid flat and ready for mealtime, they are folded and foodless, closed for business; no lunches are to be served here. Not only are they barren, they are festooned with crows, reminiscent of the Bodega Bay playground in The Birds. Fragments of graffiti can be seen but most of those pleas of remembrance have been erased or painted over. Those who once sat there are willfully forgotten. Those kids. The troublemakers. The ones that receive far greater punishment than the white kids for the same schoolhouse infractions. And the girls get it worse than the boys. As The New York Times has pointed out, “recent discipline data from the education department found that Black girls are over five times more likely than white girls to be suspended at least once from school, seven times more likely to receive multiple out-of-school suspensions than white girls and three times more likely to receive referrals to law enforcement.” And they are sent home, expelled, lost, forgotten, carelessly abandoned as carrion for the crows to feed upon.

This is the America that Simmons portrays. Well-meaning white folks will tut-tut and say how sad it all is, and perhaps make a donation to something or other that is vaguely related to a cause the name of which they cannot remember. And that is why this exhibition is so vigilantly defiant. Those antique references the artist has made are living yet. “No, White folks,” it says, “you don’t get a pass for that.” Because Black folks are not prepared to wallow, to drown in your partitioned mire of inescapable Blackness.

And no. You cannot have your statues back.

Installation view, “Gary Simmons: Remembering Tomorrow,” Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2022, © Hauser & Wirth, photo by Jeff McLane. -

POEMS

“shift work” by Evan Evans; “Enduring Romance” by John Tottenhamshift work

twin heads pillow

moments away

only seats left in the front

the forgiving distortion

the forgetting of plot

so grateful

that the light should bow

to take the shape of your mouth

a movie where she’s

so tired

from watching him

sleep

all day

—Evan Evans

Enduring Romance

There was a time when you were charmed

by my lunging, and when I found your ignorance

more endearing. But that was long ago,

when love was new and our every precious moment

felt like sunlight glittering upon the edge

of a gently breaking wave. Now closeness

means chaos, and every dreaded moment

brings me closer to my grave.

Where does all this clumsy thrusting end?

Half-mad, greedily sucking on the

desecrated manhoodof the absentee father; desire meets boredom halfway

in a stalemate of discontent, a deep and selfish love

that can only thrive in a moist environment.

—John Tottenham

-

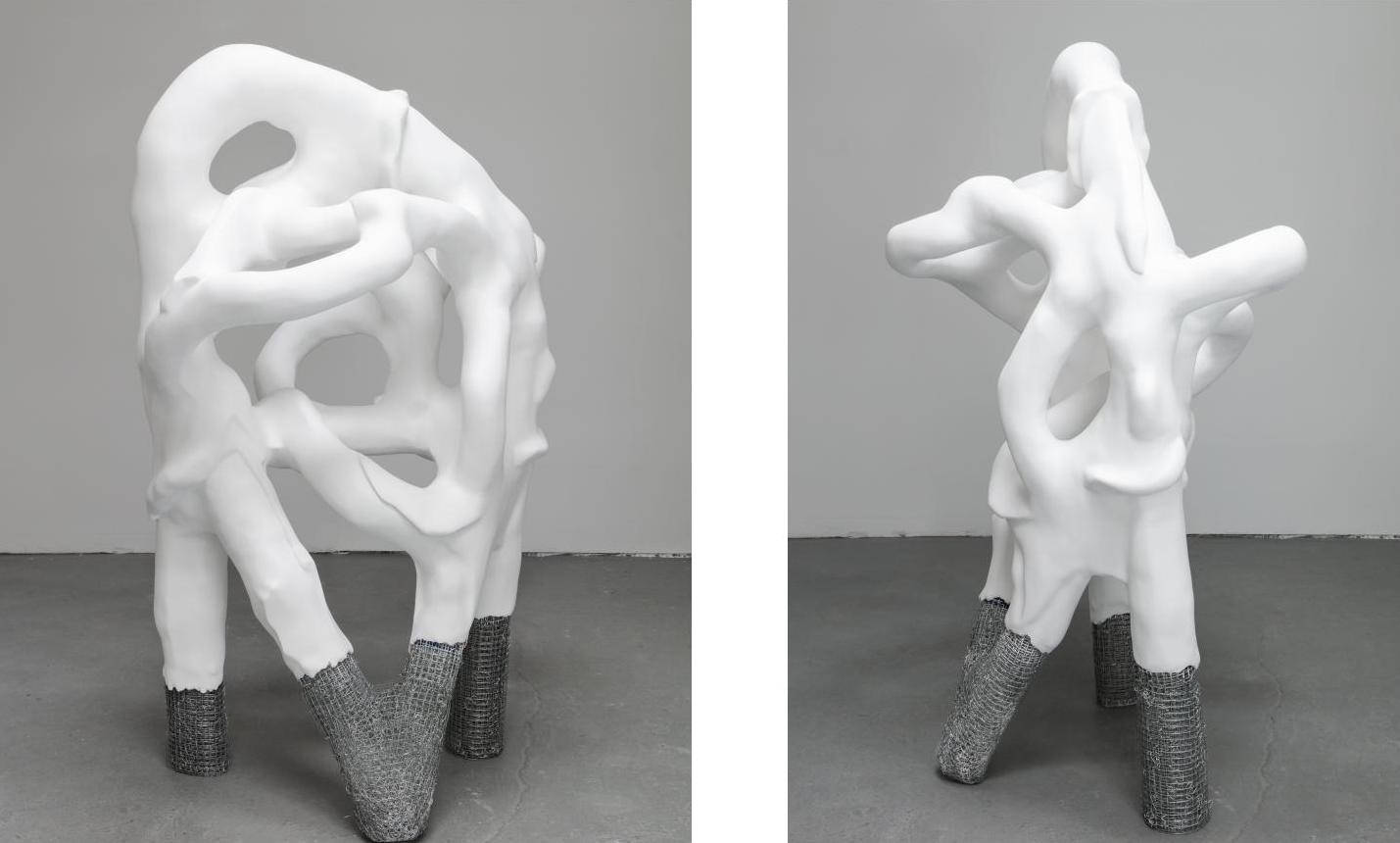

GALLERY ROUNDS: Patrick Nickell

Rory Devine Fine ArtThe tradition of organic and biomorphic form sculpture is one of the most singularly important in modern and contemporary art. Stretching all the way back to the undulating serpentine forms of the Läocoon, the tradition really took off in the early 20th century in the work of Brancusi, Arp, Moore, Picasso and others who clearly derived it from the contours of the human body. It became a way to continue the historical sculptural emphasis on figuration while conversely being a means through which artists were finally able to break with the convention of the statue to explore the phenomenon of pure form in sculpture.

Patrick Nickell, “Farmers Pride,” 2022; Courtesy of the artist and Rory Devine Fine Art In his exhibition Like It Is at Rory Devine Fine Art, Patrick Nickell continues and extends the traditions of organic form sculpture, adding some new juice to a direction that has been sadly neglected by sculptors lately. The show is noteworthy both for its displays of formal invention and consummate craft; in an era when so much sculpture is created using “readymades” or 3D digital modeling and printing, it’s refreshing to see work that is emphatically hand made. The largest work in the exhibition, Hovering Over A Loved One (2019), combines the constructivist penchant for enclosed negative spaces with organic form’s emphasis on a feeling that the work has grown like a living being. The piece also has a quality unique to sculpture in that it looks acutely different from various viewpoints, like David Smith’s iconic Blackburn: Song of an Irish Blacksmith (1950). As in all the works in the show, it compels the viewer to continuously move around it to contemplate its myriad of formal nuances.

Patrick Nickell, “Hovering over a loved one,” 2019; Courtesy of the artist and Rory Devine Fine Art Winning Battles Losing Wars (2019) – the most obviously figure-sourced work in a show of clearly abstract sculptures – suggests two struggling, wrestler-like figures. The quasi-figures are joined at the top – it’s actually one entity fighting with itself. The matte white plaster surfaces of Nickell’s forms are perfect for an art the expresses the most basic quality of any sculpture: pure form. Essential to the development of modern sculpture, the emphasis on form remains a viable sculptural paradigm, and one that Nickell continues in an art that manages to be non-derivative, formally inventive, and intellectually engaging.

Patrick Nickell, Untitled, 2019; Courtesy of the artist and Rory Devine Fine Art Like It Is

Rory Devine Fine Art

May 28, 2022 to June 25, 2022

3209 W. Washington Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90018 -

Poems

“Silicon Valley” by Rhiannon McGavin; “Vanity in Vain” by John TottenhamSilicon Valley

A cloud is the earth displaced for tracks of cable underground, underwater

A stream is the friction between content and a beckoning hand

To kindle is to adjust the climate dial in a server farm

An antenna is the arc of pesticide as it is sprayed from a plane

A bug is the noise emitted by neon signs

A web is the section of sky covered by a billboard

A nest is the time elapsed between waking and sensing an advertisement

An echo is the decomposition rate of post-consumer technological products

An amazon is the unprocessed pulp for one holiday’s supply of shipping boxes

An apple is the leaked transcript of a board meeting

A seed is one black redaction mark

To phish is when a red tree blooms in the warmest recorded January

A story is what disappears after 24 hours underground, underwater

Memory is less expensive each year

Memory is the sound a forest makes as it is felled

Memory is the thing that waits for room to grow

—Rhiannon McGavin

Vanity in Vain

To give up or give in,

to cease to take solace in

the things that I take solace in,

and give in to wanting

what everybody else wants.

That way lies ruin.

As vain, in vain, and unrewarding

as it’s been, the losing battle

I’ve chosen still beats the alternatives.

There’s no way out now, no return

to the collective dream.

—John Tottenham

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Barbara Kruger

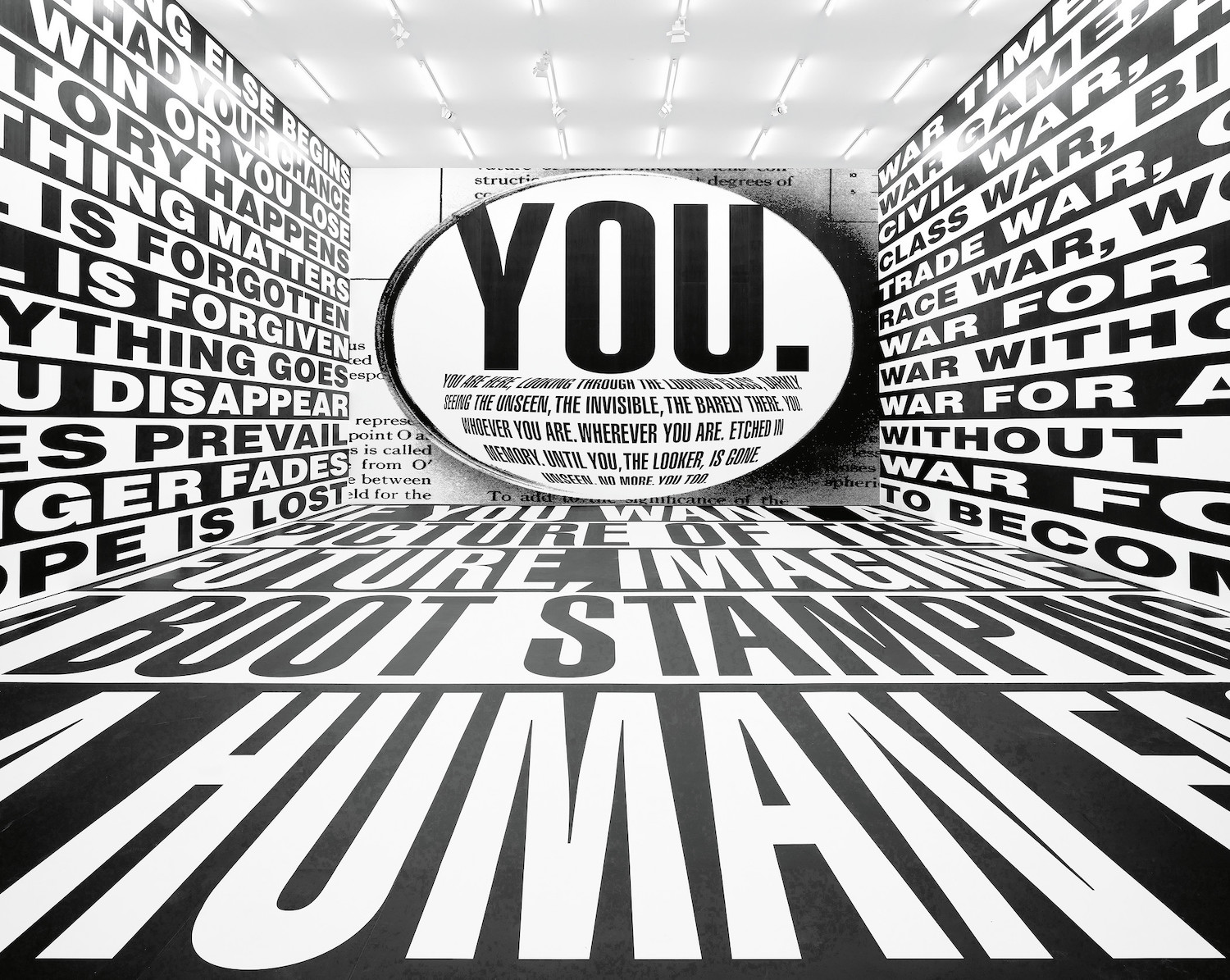

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtMe You

“Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.” is a classic Barbara Kruger experience. The exhibition serves as an introduction to those who may be unfamiliar with her work, yet also engages with seasoned viewers by re-presenting older works in grand, high tech and spectacular ways. Kruger is a master appropriationist who cleverly re-contextualizes her imagery, often enlarging the original photographs to monumental scale, or configuring them into dynamic videos. She is also an astute observer and cultural critic who uses her art to challenge, provoke, inspire and educate.

Installation photograph, Barbara Kruger: Thinking of . I Mean . I Mean You., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, March 20, 2022–July 17, 2022, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA A good place to start however, is not at LACMA but across the street at Sprüth Magers gallery. Here, a selection of Kruger’s original paste-ups—small scale, pre-digital collages— are on view. In these pieces from the mid-1980s, Kruger juxtaposes appropriated black-and-white photographs of statues, animal jaws and body parts with declarative statements, including the iconic Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face) (1981) and Untitled (Business as usual) (1987). It is wonderful to see the original mock-ups for these early pieces, then walk across the street and see them again in large-scale, digital works and room-sized immersive installations. When walking across the street viewers are drawn to billboard-sized works plastered on LACMA’s construction fence. These new pieces serve as a dramtatic introduction to the exhibition.

Barbara Kruger, Artist rendering of Untitled (That’s the way we do it) (2011) at the Art Institute of Chicago, photo courtesy of the artist and the Art Institute of Chicago Though the exhibition spans four decades of Krugers work, “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.” is not a chronological survey. The exhibition begins in a room that reimagines Kruger’s 1987 photograph, Untitled (I Shop therefore I am). In the original work, a red card with bold white words rests in the center of a black-and-white hand proclaiming, I Shop therefore I am. In this iteration, the hand holds montages of photographs by others that Kruger found copying her signature style. Kruger embraces these imitations and integrates them into her work, rather than dismissing them. Installed on one of the walls in this room is a large video display with texts that riff on the original, changing the wording to read variously I shop therefore I Hoard, I sext therefore I am, I need therefore I shop, etc. The image is separated into puzzle pieces that cohere and then break apart as the video cycles through the different variations.

Barbara Kruger, “Untitled (Truth),” 2013, digital print on vinyl, 70 ¼ × 115 in. (178.6 × 292.1 cm), Margaret and Daniel S. Loeb, New York, digital image courtesy of the artist As viewers traverse through the exhibition, they happen upon single channel videos, digital prints on vinyl, as well as room-sized, site specific installations where text, image and video projections fill the walls and floor. While the design and tenor of Kruger’s works has remained consistent throughout her career, the presentation has evolved, partly due to changes in technology which Kruger has embraced and used to her advantage. In Untitled (Forever) (2017) and Untitled (Floor) (1991/2020), digital prints on vinyl span the gallery walls and floors. It is necessary to step on and over the words and move through the space in order to read the entire text. Untitled (Forever) states: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face.” Often Kruger’s texts are about the physical body, its relationship to theory and current events. Watching Kruger analyze an Artforum article in the video Untitled (Artforum) (2016/2020), by circling and then commenting on words like ‘post-identity’, ‘post-race’, ‘post-gender’ and ‘post-human’ concretizes the depth of her thinking.

Barbara Kruger, Still from the video Untitled (No Comment), 2020, three-channel video installation; color, sound; 9 min., 25 sec., courtesy of Sprüth Magers, and David Zwirner, New York, digital image courtesy of the artist While Kruger’s works are graphically bold and eye-catching, they are always about more than what can be seen on the surface. She looks hard at war, oppression, racism, feminism, social and cultural injustices, often presenting contradictory statements and allowing them to clash. In her work, Kruger wants to get at the truth, whatever that may be at any give moment. She immerses her audiences in a bombardment of images and texts, asking them to sift through the many layers to find a personal takeaway.

Barbara Kruger

Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

March 20 – July 17, 2020

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Roberts Projects

Group Show “Wish You Were Here II”Now that we are finally emerging from the stronghold of isolation in the wake of COVID-19, the familiar phrase “wish you were here,” takes on new meaning. In Roberts Projects second visual iteration of this phrase, the nine artists in this exhibition reassert the notion of community and home, familiarity and friendship, kinship and new beginnings. Where the first show highlighted the sadness inherent in isolation, this new group of works celebrates our newfound human connections. Daniel Crews-Chubb continues his explorations into human intimacy in his vibrant series of couples and Alexandre Diop’s Autoportrait Ligamentaire, a mixed-media work on burlap is an intensely realized exploration into the notion of “self.” Wangari Mathenge’s It is What It Is, also a portrait, is unflinching in its loveliness just as Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe’s Jokey and Nana, is a luminous and colorful portrait of good friends and familiars. Beyte Saar’s Eye of the Beholder, represents the act of being seen and recognized by a ubiquitous and all- knowing God. Brenna Youngblood’s Wish You Were Here, captures the moment between being one thing and another as a folding chair appears half open, suggesting that we are constantly in a state of transformation. Ardeshir Tabrizi’s Horsemen, is a surrealistic take on being accountable as the entire image emerges from several vertical sluices of color, and Taylor White’s I am the Pilot, is a humorous look at car culture. Finally Evan Nesbit’s large free hanging painted panels are fun and enigmatic, and certainly offer a fitting welcome to newly minted gallery goers. This dynamite show ends this weekend.

Wish You Were Here II

Roberts Project

March 19 – April 16, 2022

-

Poems

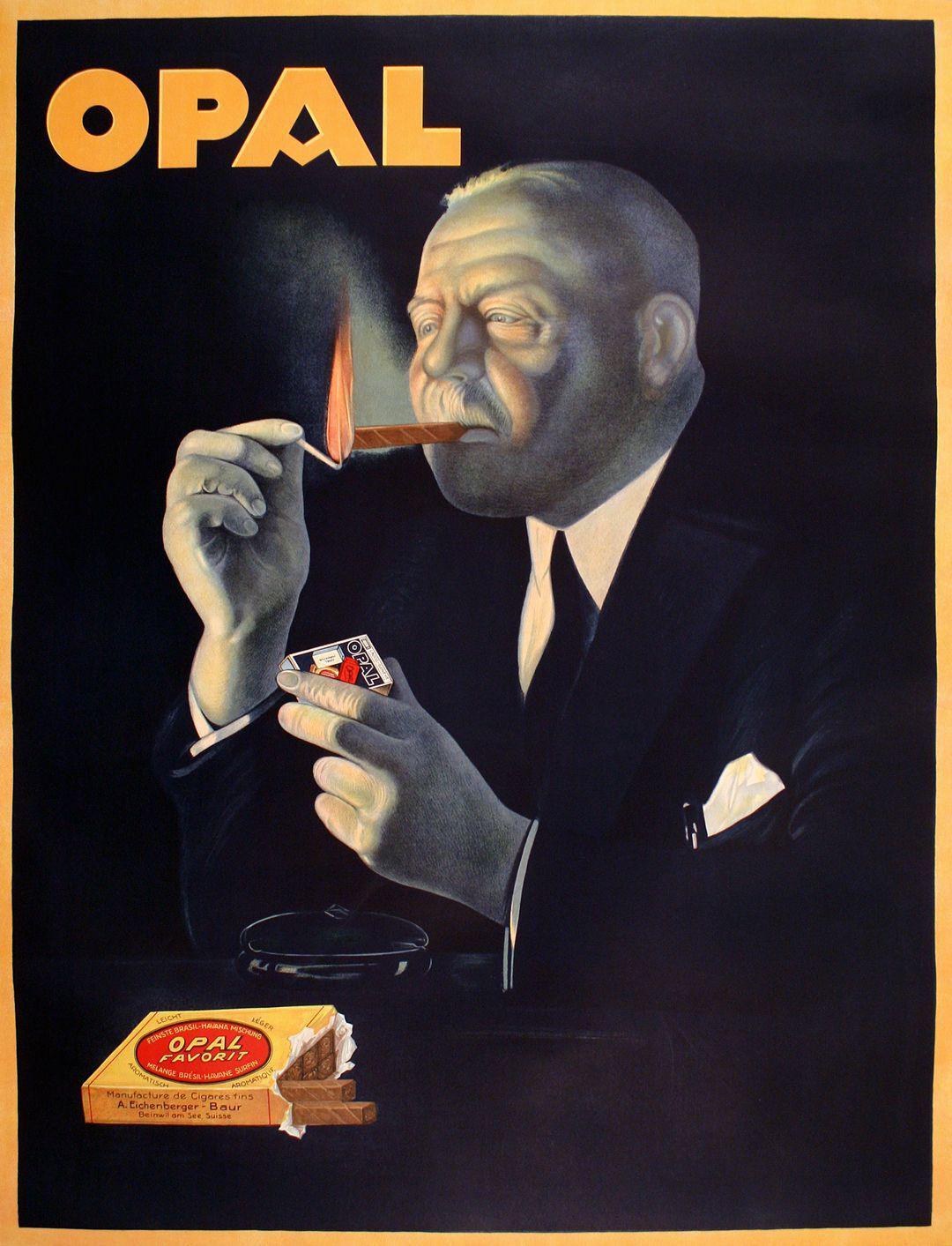

“Kiefer Lights a Big Cigar” by Klipschutz; “The Poet’s Garden” by John TottenhamKiefer Lights a Big Cigar

& waves the heavy machinery into place

He rearranges the rubble

speaking whichever language suits the occasion

He & Tony saunter through a tunnel in the South of France

“It’s my gesture” is what he says about his art

His use of lead & straw reminds me of a Jack Gilbert poem

Kiefer & Werner Herzog must never meet

If they have, they must never admit it

(When Gerhard Richter met Stockhausen

neither one was left unscathed)

Kiefer carries the weight of the world on his shoulders

& shakes it off with a flick of his cigar

—Klipschutz

The Poet’s Garden

Without these words, without these needs,

how much simpler life would be: free

from invidious and irrelevant comparisons,

resentful longings, and obscurely realized

self-actualizations: a life less whole,

a lifeless hole… but a destiny, at last,

within my control – striving

only towards resignation,

a worthy goal.

—John Tottenham

-

Post Frieze LA: The KNOW Contemporary

Group Show “BLACK”Enlivened by the energy of Frieze Week LA, I went to The KNOW Contemporary to view curators Knowledge Bennett and Charles Moore’s group exhibition, “BLACK.” To my surprise, I’d stumbled into the installation’s culminating event, a panel discussion with its artists and gallerists. Seated amongst the art world’s most prominent innovators, I was moved to witness a panel of Black creators discussing blackness as both cultural identity and sublime aesthetic.

This multifaceted lens animates “BLACK,” which feels both suspended in cosmic space and grounded in political reality, granting it a uniquely ethereal quality. As viewers entered the gallery, we were met with three works by Bennett (who is included in the show). Painted with acrylic and diamond dust on canvas, they are presented in succession, their geometric symbolism and incandescent surfaces composing a delightfully monotonal abyss. Directly to their right, Bennett’s How Long Does it Take to Make Devil? (2021) reads “MAY 25, 2020,” referencing the date of George Floyd’s murder, and the crest of a cultural awakening. This juxtaposition of the political and the transcendent characterize the exhibition, which seeks not to reconcile the complexity of blackness, but surrender to its expanse.

Installation View. BLACK at The KNOW Contemporary. Photo courtesy of Artsy Continuing through the gallery space, we encountered the paintings, mixed-media works, and sculpture of nine Black contemporary artists which meditate on the darkest hue and the diaspora it has come to represent. While some works depicted Black people and the social realities that shape them, others were decidedly abstract, engaging black on purely aesthetic terms. It is this kaleidoscopic gaze on blackness—as color, culture, and consciousness— that lends the exhibition its particular magic.

Situated within a discursive landscape that seeks facile solutions to our racial woes, “BLACK” represents a historic departure. By boldly embracing multiplicity, the group exhibition creates space for Black artists to explore the complex—and often competing—truths of their existence. It is in this acceptance of manifold truths that we might understand blackness in its totality — as unapologetically and infinitely abundant.

BLACK

The KNOW Contemporary

422 S Alameda St., Los Angeles, CA 90013

Exhibition Dates: Feb 16 – Feb 20, 2022

-

OUTSIDE LA: Andy Warhol

Aspen Art MuseumIt’s rare to encounter a Warhol exhibition with something genuinely new to say, but somehow Lifetimes (a co-production of Tate Modern, Museum Ludwig, Art Gallery of Ontario, and Aspen Art Museum — its only U.S. venue) accomplishes it. Thanks to both the thoughtful selection of key works and rare, germane ephemera from every stage and vector of the artist’s decades-long career, as well as the bespoke, site-responsive AAM exhibition design by artist Monica Majoli, audiences get evocative experiences along with an intimate re-education on the canon centering the artist’s biography and personal identity in the conversation.

Majoli described her approach to Andy Warhol as “both concept and a person,” and in this she succeeds, deftly weaving the range of everything we think we know into a deeper dive into his strong family ties, religious life, queer identity, restless curiosity, and prescient cultural critique. As the exhibition proceeds in a double thread of biographical chronology and episodic creativity, explicit connections are illuminated between what his life was like at key moments and the art which he produced at those times. Following a rather Proustian early-childhood period of illness, along through his lifelong closeness and artistic collaborations with his pious, part-muse mother, we see the early attempts to reconcile his working-class ethos with the modern obsession with celebrity shenanigans and the culture’s worshipful trade-in of god for glam.

Installation view, Andy Warhol: Lifetimes at Aspen Art Museum From his early life as a successful ad guy during literal Mad Men times, the show draws a straight line to later iterations of his career in which he gleefully leveraged his fame and personal brand into starring in lucrative commercial ads and even Love Boat guest spots, along the way founding of the avant-garde magazine Interview as a savvy, reverential vehicle promoting the same aesthetic that animated the paintings and films (not to mention to the epic situation with those polaroids) he was making. The post-New Wave, the expressionism-inflected explosion of gestural color, the eroticism of infinite variation, the fetish for style, the addiction to death- and doom-scrolling, and the emerging realization that every choice we make is art, as for better or worse has the power to make us special, maybe — all of this from 40 and 50 years ago will be familiar to anyone who is alive right now. But so too with his humanity, his searching, his doubts, his masks, his pranks, and his prayers.

Oxidation Painting, 1978 on view in Andy Warhol: Lifetimes at Aspen Art Museum A suite of galleries devoted to the role that his queerness played in Warhol’s personal life explicates the narrative through the lens of his choices of medium and subject, connecting sublimated political narratives with tender emotions, and continuing to inform layered understandings of the work. Both controversial and reserved, infused with illuminated relationships to art history and most importantly his own inner life, the choice to gather together these suites of frank but delicate male nude ink drawings from 1954-57 and 1977-78 with large Camouflage (1986) and Oxidation Painting (1978) canvases was inspired. It highlights the aspect of the former which overtakes a militarized pattern associated with masculinity and violence with a luscious queer palette and sparkle, and grounds the latter in the homoerotic physical, bodily process of achieving these chemical responses to AbEx — another machismo-dominated scene that needed queering.

Ladies and Gentlemen, 1974 on view in Andy Warhol: Lifetimes at Aspen Art Museum In the next room, the oft-cited Christopher Makos film Factory Diary: Andy in Drag 2 (1981) anchors a funhouse mirrored disco spaceship installation of the Ladies and Gentlemen (1974) series — portraits depicting trans folks of color, cast from bohemian theatre society and from the gay bar by the Factory. The room is both glorious and a little uncomfortable, but linking these to the film is salient, because on the one hand their juxtaposition signals a broader acceptance of gender-fluid identity, but on the other hand the portraits are themselves problematic, even exploitative. At first the infamously poorly-paid sitters were anonymous or at least unnamed publicly; subsequent scholarship revealed their identities. Questions remain, as this series can be seen as both immortalizing and erasing at the same time. The film both clarifies and complicates this equation, and in its own right serves flirtatious melancholy while evoking the years of similar films which Andy made of all who came through his doors.

Screen Test videos, 1964-66 on view in Andy Warhol: Lifetimes at Aspen Art Museum In the final set of galleries, several of the Screen Test videos (1964-66) flicker in a darkened room, hypnotic and lush; Duchamp, Hopper, Dylan, Nico, Ginsberg, and more just stare back at you with artificial but intense attention. It’s like a life flashing before the eyes of a dying man. These are projected across from a lesser-known and more final body of photo-based works with hand sewing, taking older photographs from 1976 and viscerally, visibly crafting new objects from them in 1986 — a year before his death and very much at the height of the AIDS crisis. This expression of remembering the past and giving it concrete form in a way that directly references a body in need of repair is a ritualistic act, a reach for permanence perhaps, or a look at beginnings as things everywhere were seeming to end.

Andy Warhol: Lifetimes

December 3, 2021 – March 27, 2022

All photos by Shana Nys Dambrot.