The progress of his career has been a methodical march; carefully scripted, stubbornly stage-managed, and precisely choreographed—each subsequent exhibition enhancing the shudder of an already disconcerting thrum. The result of such a steady and painstaking pace has delivered an exhibition catalog worthy of MacArthur, yet his current exhibition is no laurel-chasing spectacle, it is a personally brazen and bitter step forward. Not satisfied to merely convey pathos, or defy hoary convention by shouting Macbeth! backstage, the artist is concerned with far more pressing matters. Gary Simmons is here to bring the pain.

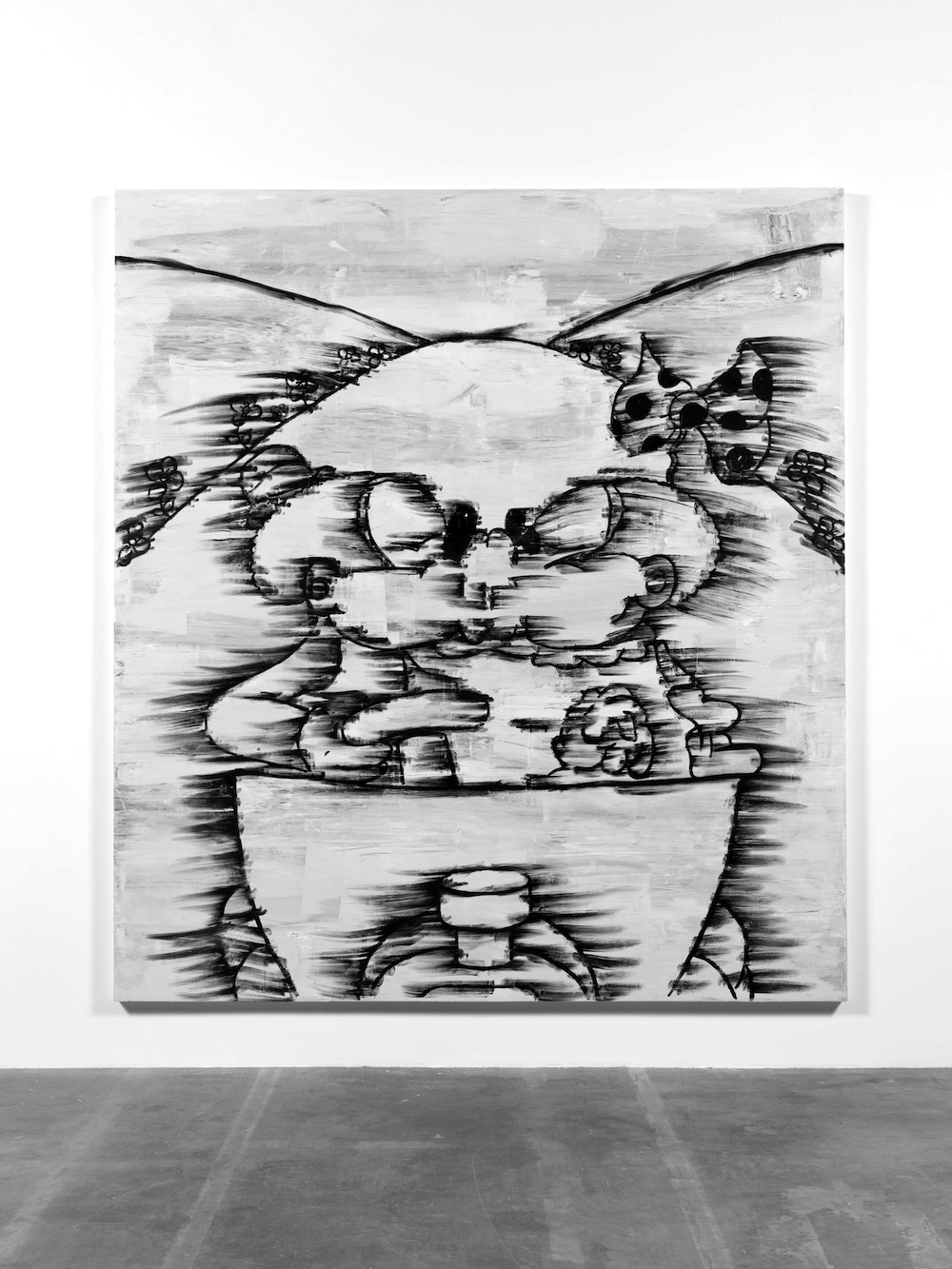

Comedic, vulgar and unsettling, these apparent cartoons appear buoyant and frivolous. One might associate his imagery with graffiti (one would be wrong) or the vacuous fluff committed by Banksy (another misapprehension despite its uncanny fluence). Yet despite their varied black and white backgrounds, with wittily minimal accents of color—these characters force-feed the viewer mouthfuls of chalk dust. The fresh canvases on the wall are large (all 2020–21), the wall paintings larger yet, but the characters spit a comical bile, an intentionally acidic hocker in the eye of the beholder. These are ghost paintings, with characters that continue to haunt. They are dead and yet they live: in our bitter racist politics, our unequally funded schools, our trigger-happy policing, and freelance “white replacement” spree killers. Lynch Frog, features a character haplessly hanging, a peril no doubt brought on by his own darned foolishness. 88 Fingers Fats is so eager to entertain that he spirals himself into tar and turpentine. The paintings have the patina of the ancient but maintain an ever-potent bile, pantomimes that so tickle the funny bone of the secret cracker that the Warner Brothers’ Censored Eleven have risen from the grave and are once again enjoying distribution. These cartoons—a vile hoot for the unreconstructed—feature Coal Black and the Sebben Dwarves, where the mean old queen is nothing but impossible bosom, saucer eyes and face enveloping lips; Jungle Jitters, with a plump googly-eyed native whose nose ring is so expansive it does double duty as a jump rope; The Isle of Pingo Pongo, bone-coifed natives with lower jaws so extensive they serve as dinner plates; finishing with Goldilocks and the Jivin’ Bears, where a black wolf in grandma drag is chased up the chandelier by a telegram porter who pulls a gat and speaks in the voice of Jack Benny’s Rochester. Compared to the more egregiously bigoted imagery contained within, the titles and show descriptions seem downright elegant.

88 Fingers Fats, 2022, paint and chalk on wall, 144 x 657 in.; © Gary Simmons, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo by Jeff McLane.

In a long career that has paced steadily toward a potent display of Black visibility through a rendering of its absence, Simmons has employed minimal tools to create elemental imagery. His 2010 exhibition titled “Black Marquee” featured sparse text on blank walls at Anthony Meier gallery in New York, a haunting contrast to the space’s renaissance revival interior. Rooms and corridors were emptied, leaving only the white arches and columns contrasting the near matte black walls. Streaked upwards and downwards the nominal white lettering described Blaxploitation films, creating an elegant accompaniment of X-ray reversal to Marcel Broothaers’ La Salle Blanche (1975).

Star Chaser, another of the sweeping paintings, is a tapestry of black—of eager hope tempered by bitter disappointment. His vast rendering of night is full of stars but all of them seem to be dying, not shooting. It is a stargazing portrait of embittered aspiration, the Pecola Breedlove knotted fitfully inside us, imbibing exterior resentment, and believing it porridge. It echoes in sentiment the artist’s Balcony Seating Only (2017), his polished floor reflections at Regen Projects, where segregated cinema reveals its aspirational dead end by the stairway to the Colored section, a steep and unsteady climb leading nowhere. Jittery lovers enact a romantic ritual in the 44-foot chalkboard fit of erasure, Lindy Hop. He presents a posy; her bowed hair reacts. They don’t yet know that this will be their high point, that ever after will reek of torment. Their youth is a buoyant ignorance and hard lessons are on the horizon. As in his Fade to Black (2017) at the California African American Museum, hopeful fantasy is again tempered by heartbreak in the race films Souls of Sin and Murder on Lenox Avenue. Cinema, a variety to which the Simmons imagery belongs, is a global language, and his figures are richly illustrated and quiveringly alive in the grandest of the rooms in the Hauser & Wirth depot; Lindy Hop, Star Chaser, and 88 Fingers Fats dominate the show as if in an arena. They silently overwhelm.

Splish Splash, 2021, oil and cold wax on canvas, 84 x 108 in.; © Gary Simmons, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo by Jeff McLane.

The circuitous walk-through ends at the gallery’s garage door exit; it is more than suggestively the end of the road. In this final work, a subtler and damnably haunting installation, fairly spits its defiant title, You Can Paint Over Me But I’ll Still Be Here, which could address both itself as well as the hung canvases and wall paintings previously viewed, of no longer living yet never dying stereotypes. In this purposely less elegant expanse, the artist has suggested a school lunchroom. Its dining tables, however, are not laid flat and ready for mealtime, they are folded and foodless, closed for business; no lunches are to be served here. Not only are they barren, they are festooned with crows, reminiscent of the Bodega Bay playground in The Birds. Fragments of graffiti can be seen but most of those pleas of remembrance have been erased or painted over. Those who once sat there are willfully forgotten. Those kids. The troublemakers. The ones that receive far greater punishment than the white kids for the same schoolhouse infractions. And the girls get it worse than the boys. As The New York Times has pointed out, “recent discipline data from the education department found that Black girls are over five times more likely than white girls to be suspended at least once from school, seven times more likely to receive multiple out-of-school suspensions than white girls and three times more likely to receive referrals to law enforcement.” And they are sent home, expelled, lost, forgotten, carelessly abandoned as carrion for the crows to feed upon.

This is the America that Simmons portrays. Well-meaning white folks will tut-tut and say how sad it all is, and perhaps make a donation to something or other that is vaguely related to a cause the name of which they cannot remember. And that is why this exhibition is so vigilantly defiant. Those antique references the artist has made are living yet. “No, White folks,” it says, “you don’t get a pass for that.” Because Black folks are not prepared to wallow, to drown in your partitioned mire of inescapable Blackness.

And no. You cannot have your statues back.

Installation view, “Gary Simmons: Remembering Tomorrow,” Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2022, © Hauser & Wirth, photo by Jeff McLane.