Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Tulsa Kinney

-

JOHN WATERS’ BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION: THE NAKED TRUTH

The WallisCan John Waters offend anyone these days? It hardly seems so. “I’m tired of being respectable,” he quipped at his show, “John Waters’ Birthday Celebration: The Naked Truth,” admitting he might be relatively mainstream today. He listed all his recent awards, and now he is greedy for more! “I want the Nobel Piece of Ass Award!”

Whether he can still offend or not, Waters doesn’t disappoint. This might be the fifth time I’ve seen Waters on stage, and once again, hilarious and flawless. His sold-out show at The Wallis theater last Saturday night promised to reveal all, and he didn’t hold back.

My first Waters live show was in the late ‘80s in LA and involved a beehive-hairdo contest. I took special care to sculpt my hair big and dress outrageously, but sadly, I wasn’t picked to be in the contest. That was just unacceptable, so I shoved my way into the contestant line—a classic Divine maneuver. I later realized I was probably competing with a bunch of drag queens, which was not exactly fair!

So on Saturday, I arrived especially early to people-watch, expecting to see at least a few Divine impersonators and some crazy wild outfits, but there were none. This crowd could have easily been attending a folksinger concert, albeit a gay folksinger. As I sat sipping my martini, the empty seat beside me suddenly became occupied by a young guy in his twenties. He was friendly and we started talking. I jokingly asked him if he felt like he just walked into a nursing home event. He did laugh but defensively pointed out the few young people sprinkled around us. When I asked if he’d ever seen Waters live before, he replied, “No,” referring to Waters as a “comedian,” which jarred me!

That got me thinking about how Waters remains relevant with his varied mix of fans. I’m old-school, as my introduction to Waters was his classic early films, but many fans today haven’t even seen Female Trouble, and their introduction to Waters is more like Hairspray. (I used to roll my eyes when I would hear someone say they love Hairspray, not even knowing about his earlier films, which really put Waters on the cult-status map.)

Waters is a polymath with his fingers in all the pots. He never stops producing, whether it’s a new book, his first novel (only a few years ago), a film, or a live tour. He is constantly on the go and remains a fixture in art and culture. Artforum and The New York Times routinely check in with what his favorite movies or books might be. Everyone wants to know, what does John Waters think of this or that? The Baltimore news media even reached out to see what he thought about the bridge that collapsed, which he told us onstage, seemingly rather amazed himself.

What keeps Waters still so fresh and alive? My first response would be, he’s still fucking hilarious (and stopped smoking years ago). He’s unabashed and authentic. He came on stage with his salvo of rapid-fire jokes: one right after the other, pacing back and forth, no pauses or glitches. Since this was a birthday tour (not afraid to reveal his age as most celebrities), he addressed getting old, and he doesn’t have a problem with aging; in fact, he loves it and finds whacking off to walkers very satisfying. (I must introduce him to John Tottenham’s sexy women-and-walkers paintings series.) He does not refer to himself as a male cougar (Thank God!). What he does have a real big problem with is shitting, and he’s not talking about constipation. I’ve read of a good bowel movement being compared to sex à la Charles Bukowski, but Waters couldn’t disagree more. The very act of unloading he finds a disgusting task—why did God design us this way? The one thing he looks forward to when he’s dead is never having to take a dump again.

Thankfully, we were spared the subject of today’s politics, with one exception pointing out that while all the protests are fine and dandy, what we really need is another Bloody Sunday if we want to make a difference (and he is so right).

He seemed to be even raunchier than ever, delivering his zingers with verve and conviction, snarling and twisting his face when he spat out, “I don’t like strangers touching me in a nonsexual way.” His suggestions for political correctness while talking dirty in bed were a riot and most crude. He makes fun of heterosexuals the way Black comedians ridicule white people. Today’s porn is no fun anymore now that it’s free, and he urges people to fulfill their every fetishism: “Go ahead and fuck that tree, trees are whores!”

Waters was on that night and delivered jokes, dare I say, like a true standup comedian. Known for his dedication to his fan base, he even stuck around to answer questions from the audience afterwards. It appeared once or twice he might have lost his place, taking himself back to the note card on the stool placed onstage with a bottle of water (of which he never took one sip), but that was even seamless as he muttered out loud to himself, “Let’s see, what else do I hate…”

-

Seeing Detroit Through Fresh Eyes

Taylor Renee Aldridge Returns to her Hometown to Head Modern Ancient Brown FoundationRecently I had the opportunity to visit Detroit for the first time in my life. What a magnificently diverse city bustling with bars and restaurants on every corner in the downtown area, with one of the top encyclopedic art museums in the nation where the socialist mural by Diego Rivera can be seen.

No wonder Taylor Renee Aldridge left Los Angeles to return to her native Detroit, I thought to myself as I was tooling around downtown in the brisk autumn weather. It was early evening when I arrived, and the city was abuzz with long lines for dining and people spilling in and out of bars. After losing over a million of their population, the city is having a bit of a renaissance. Just 15 minutes away, the burgeoning Little Village arts district is where Aldridge serves as executive director of the Modern Ancient Brown Foundation (MABF).

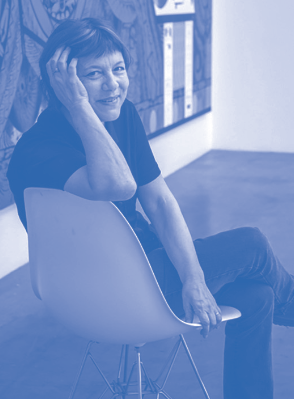

Taylor Renee Aldridge. Photo: Bella Lopez. Before packing her belongings and her two schnauzers for a cross-country road trip with her partner back to Detroit, Aldridge resided in Los Angeles as the visual arts curator and program manager at the California African American Museum (CAAM) for four years. One of the exhibitions she worked on featuring the works of artist Simone Leigh is still on view at CAAM and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Besides reuniting with family and friends, Aldridge stated another motive for returning to her hometown was, curiously enough, climate change. “Being in middle America, surrounded by the Great Lakes and having affordable housing,” she noted, “and to be rooted somewhere,” all made the decision to return an easy one.

I met Aldridge for a sit-down interview to discuss her new position at MABF and what her goals might be. Dressed in a casual pantsuit of neutral colors and sensible shoes, the bespectacled Aldridge is soft-spoken and deliberate with her words and surprisingly young for all her accomplishments in the art world thus far—she is only 34 years old.

The Shepherd. Photo: Katie Greenstone. Located on the third floor in the arts complex called The Shepherd, MABF was founded in 2019 by Detroit-native, Chicago-based veteran AbEx painter McArthur Binion, offering residencies and fellowships to the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) community. The Shepherd, a 110-year-old repurposed church, is the star of the Little Village development, providing a public library, art galleries, and performance spaces. Besides hosting MABF, it is a community-based cultural center where every room has been meticulously and tastefully restored, including a room where Mass was once held—I almost slipped into a confessional booth; I could hear Father calling! The building became an arts complex when real estate moguls and gallerists Anthony & JJ Curis purchased the grand church on a more than three-acre campus, including a skateboard park and numerous public sculptures, complete with rectory and, soon, a local bar!

Residency Space. Photo: Kyle Powell. MABF offers four-month off-campus residencies to post-bachelor artists. Aldridge expressed that this time for artists can be especially daunting as many people rush into their masters, “People are under so much pressure to produce and keep going and constantly having to figure out how to make a living. That pulls people away from being creative, and creativity requires imagination, requires freedom of thought, requires leisure, reading, exchange of ideas. And I don’t feel that artists are getting that,” Aldridge explained. “It’s my hope that they can come through this foundation and feel free to just … imagine.” The residency provides a stipend that makes it possible for artists not to have to work during that period.

Fellowships are granted to the more seasoned scholar and last for three weeks. “For someone in art history, or comparative literature, some sort of advanced study, we accept all scholars who are engaging in the PhD process,” Aldridge told me. She would also like to see a “cross-collaborative exchange and cross-pollination, in theory, between scholars and visual artists. That’s one of my goals in developing that two-pronged offering.”

Fellowship Space. Photo: Katie Greenstone. To be fair, Aldridge had only been in her position for three weeks when we met, but she exudes confidence and articulates her intentions impressively. For instance, when I asked if MABF would include seminars and panel discussions for the arts community, she replied in the affirmative and plans to do some experimenting with the traditional platform. “It’s a matter of collaboration; I want to play with the form of a lecture because that can get a little boring,” she admitted with a slight titter.

Making sure that she’s of service to the artists within the program, but also artists within the city of Detroit, is one of Aldridge’s visions in her new role at MABF. “There’s a wide range we accept, a number of different types of scholars, particularly people who may be attending to BIPOC and Queer discourse,” she said. She wants to specifically target people who may not have access to an MFA program or may not even have access to a community of writers and other artists who can provide feedback. “I’m interested in getting to the basics of what are the ways in which we can grow artists’ practices here,” she said. “How can we connect them with gallerists, with seasoned people in the field so they may figure out ways to sell their artwork or grow their practice; those really tangible needs.”

Aldridge talked about her experience growing up in Detroit and how she got turned on to the arts when her grade school teacher introduced her to the Black female artist Lois Mailou Jones. She got hooked on art, and was thrilled to know that people can make a living doing art. Then her high school teacher gave her a book on Clement Greenberg and she started to read about criticism, “And I thought, oh, so you can make art and then there’s all this discourse that can happen around your art or in conversation with art, and that was just really interesting to me as a young person, and someone who is just really interested in dialogical exchange and people learning from each other.” She added with a laugh that we have a lot of critiques about Clement Greenberg—now that we’ve evolved!

Her interest and discovery involve other aspects of the art world and she wants to share her knowledge on how the art market functions. “I’m thinking about those people as a particular audience, who may want to know more but don’t know where to begin,” she said, adding that she’d like to bring peers and colleagues to the city who are successful in the art industry and those administrative positions. “Demystify the pipeline” is one motive she’d like to accomplish. “Like, how do you become a curator, how do you become a scholar, how do you become an artist?”

For more information: https://www.modernancientbrown.com; For information on Fellowship applications: https://www.modernancientbrown.com/the-fellowship-application; For information of Residencies: https://www.modernancientbrown.com/post-bac-artist-residency-application

-

From the Editor

Sept/Oct 2024; Volume 19, issue 1 Dear Reader,

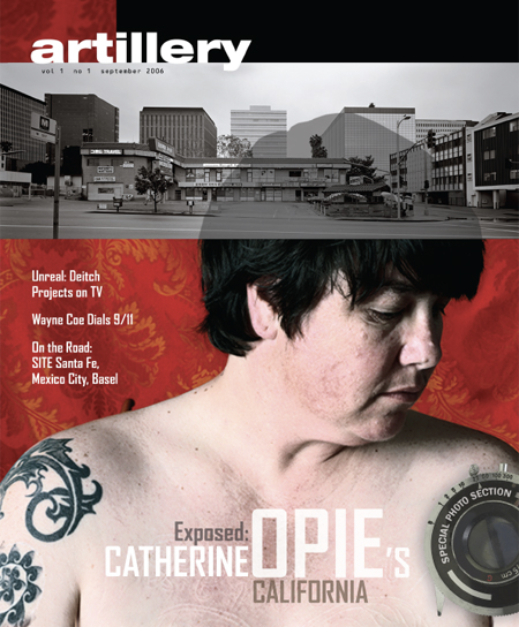

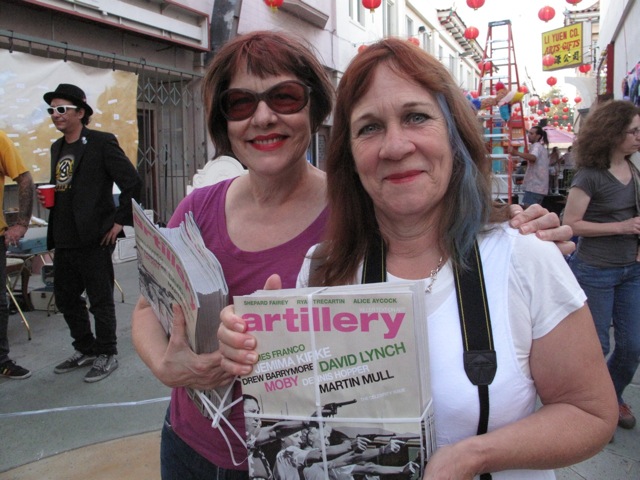

Dear Reader,I have good news and bad news. Let’s start with the bad news: This, after 18 years, is my last editor’s letter. What an incredible journey it has been. Here’s the good news: Artillery will still carry on! More on that later.

I started this magazine with my late husband, Charlie Rappleye, in the summer of 2006. This career-turn was a surprise to me, as being an editor of a magazine was never on my list of what I wanted to be when I grew up. I’ve been an artist all my life. Whether I want to reenter that world after this, is another question. After being the editor of a contemporary art magazine in Los Angeles for nearly two decades—I now feel that I know too much. I’ve seen the machinations of the art world, and it’s not the prettiest picture, certainly not one I want to jump right back into as an artist.

But for now, I’d like to reflect on that incredible journey with the art world. Back in 2006, there was a severe dearth of readable LA art publications. A few quarterly nonprofit academic art journals were in circulation, but I found them to be deadly, and most people would silently agree. I had edited the local naughty art zine, Coagula, for a year, and enjoyed that immensely: I loved publisher Mat Gleason’s unfiltered take on the art world, but I wanted something in between—something that reflected the real world of an artist, something more daring and iconoclastic. Some humor, even?

By Artillery’s third year, a new tag line was added to our logo: The Only Art Magazine that’s Fun to Read! At that point we had comics, poetry, opening-party photo spreads, reports from Gotham City. There were fleeting columns with names like Throttle, The Poseur, Outer Space, Retrospect (by THE Mary Woronov), Under the Radar, AmmuNation, Private Eye, Off the Wall—and my fave, On the Wag with Mitchell Mulholland, our gossip column that was so snarky and sardonic that I was forced to kill it in the interest of survival.

We were off to a good start: The LA art world embraced us, and we hired Paige Wery at the end of our first year. Paige had never been a publisher, but none of us had experience in running an art publication either, so we took a chance. Turns out, she was a natural and boosted the magazine to another level. We went to art fairs, book fairs, threw parties, poetry readings and art debates. We traveled to New York, San Francisco and Miami. We were a great team—certainly a highlight for me in the magazine’s early years.

Getting to know the art world through a different lens sometimes soured me. Often, it just wasn’t my scene; I felt like an interloper. Then I’d run into artists like Mike Kelley, and all the sourness would disappear. He was so real and unpretentious. At art openings he was a delight, and we would crack wise. I would routinely pester him to let me interview him and eventually he agreed. I told him I’d contact him soon.

That’s when Kelley preempted me and sent a “letter to the editor” that bitch-slapped me about being maligned in our gossip column, and he demanded we cancel his subscription immediately. He added that he was looking forward to wiping his ass with the magazine, especially the Mitchell Mulholland page.

I think we all know how this story ends. Yes, I did get an interview with Kelley, but tragically it was his last interview. He was on the cover of our January 2012 issue when he took his own life. The interview was extraordinarily profound and eerily prescient. What happened was beyond heartbreaking.

Of course, I will never be able to blot that out of the magazine’s trajectory. The irreplaceable loss of Mike Kelley seemed to take the life out of the art world for a while. Why did he do it? He was right on the edge of grand success, the kind artists strive for, having just signed on with Gagosian. But he didn’t seem to be relishing it. In our interview he kept mentioning to me how his father referred to him as a Martian.

Being an artist or even proclaiming you were an artist used to feel like being an outsider or someone on the fringe. It wasn’t as acceptable or widely embraced as it is today; it certainly wasn’t thought of as a prudent career choice. With the plethora of art schools in Southern California churning out artists who have chosen to stay in LA, Artillery found no shortage of content to cover. A few times I invited our contributors to edit a theme they wanted to delve into, and many ended up as our most provocative issues. Contributor Tucker Neel pitched a “Queered” issue back in 2011. He gleefully pointed out that our cover of New York artist Kalup Linzy was the complete opposite of LA’s other art magazine, which at the time featured Ed Ruscha on its cover. I probably don’t have to spell it out, but, uh … straight old white male vs. queer young Black artist? In many ways, I felt Artillery was ahead of its time, certainly a unique publication. We had a 2008 issue on race long before the BLM movement, and a sex issue that had clients vow that they would never advertise with us again. One coverline, Contemporary Art Hates You (my John Waters interview) had my publisher screaming, “It looks like it says, ‘Artillery Hates You’”—I secretly loved that. Our Celebrity issue with Martin Mull on the cover was sort of genius, I must admit. I truly felt our magazine was the only art magazine that was fun!

And I did have fun with the magazine, but now, I’m not having as much fun, and for me, that means it’s time to move on. I believe what I created was and is something important to Los Angeles, being a significant art center. I hope you do too. That’s why it’s time for me to go and let someone else come in with fresh ideas and shake things up a bit. My successor is Daniela Soberman, whose first issue will be November. She believes in Artillery and knows its value in a big city like LA, as I did, and knows it can grow and maintain its integrity and devotion to quality art journalism.

With that, I bid my adieu. It’s been a great ride. I cannot thank my loyal freelancers and staff enough for all their dedication, hard work and enthusiasm. Many of you will be lifelong friends—such a treasure to me. And our advertisers, you literally kept us alive with your support and belief in Artillery. I know some of you had to rob your piggy bank to pay for that ad, but you knew the importance of having an excellent art magazine. Journalism is a dying art, and I have such respect for our advertisers that wanted to reward and keep that alive. And I didn’t forget about you, Dear Reader, for we simply would not exist without you.

Lastly, Artillery carried me through good and bad times in my own personal life. I never missed an issue, even when my husband died, going on six years now. I knew it would be the only thing that could get me out of bed during that deeply dark time in my life. Charlie believed in Artillery and wanted it to succeed in every way. I want that too, and now I get to sit back and watch its legacy live on.

-

From the Editor

July/Aug Volume 18, issue 6 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,As a kid, I didn’t get to do much traveling. The family trips we took were always by car to visit relatives, somehow miraculously fitting seven of us into a big two-toned Oldsmobile. My dad used to roll down the window, just a sliver, to blow out the smoke from his cigar. On our way to Chicago, where my Italian grandparents lived, we usually passed through St. Louis. We never stayed there, but sometimes we got stuck in traffic and detoured into the city on a boulevard with shops, theaters and bright lights, with cars honking and skidding on the wet pavement in the early evening mist. I loved the handsome red-brick houses all lined up, some of them lit up with Christmas lights, as most often we were traveling during the holidays.

This is when my mom would roll down her window and sigh heavily, “I love the smells of the city.” It became a family running joke, and we teased her mercilessly with fake coughing and choking while holding our noses.

I’m with Mom: After being raised in a tiny southern Missouri town, I loved every minute in the city. Chicago, where my mom grew up, was a thrill beyond belief—Lake Michigan was the ocean, the Chicago River, a canal in Venice, and the Chicago L was better than a Disneyland ride.

This was the extent of my traveling as a youth, and I felt beyond fortunate to have had the experience; it enriched my life in so many ways. My exposure to the Chicago Art Institute played a huge part in my lifelong passion for the arts. The different cultures and diversity in the metropolis opened my eyes to a whole other world. Travel naturally elevates one’s tastes and experiences, even if it’s not that far from home.

In this issue, our Ask Babs columnist answers a reader who wonders if they should be traveling to art fairs and biennials around the world to enhance their burgeoning art career. A resounding yes, Babs replies, in a cautious manner though—she recognizes not everyone has the means to go jet-setting and suggests the next best thing: visiting websites, watching films, and reading about foreign places.

Our Summer Travels issue offers just that. New York contributor Sarah Sargent focuses on the positive in this year’s Whitney Biennial, an otherwise “meh” show. LA contributor Alexia Lewis was invited to Richmond, Virginia, to attend a ceramics arts conference where she finds the art community’s way of dealing with their glaring Confederate past surprising and hopeful. Patricia Watts takes us to Italy for the Venice Biennale; this year the art gets real. But if you’re an Angeleno just staying put, a short trip to Orange County might be worth your while. Writer Liz Goldner discovers California gold at the Hilbert Museum’s newly expanded space. The massive California scene-painting collection will certainly take you on a Golden State journey. And we invite you to take that journey with us too.

-

PEER REVIEW

Tom Knechtel on Thomas AntellTom Knechtel, a Los Angeles–based artist who shows with PPOW in New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art here in LA—where his exhibition, “The Hare in the Studio,” just ended in June—is known for his intricate paintings and drawings, often depicting himself, animals and important players in his life. Although one might assume his work is autobiographical, Knechtel insists it is not—“It’s personal and I am often in the work.” The other important people in his life “all become actors who are passing through the work.” Knechtel skillfully executes pencil, ink, pastel and

silverpoint drawings with the deftness of the Old Masters. Each tool dictates his content, for instance, silverpoint which, by its nature, he tells me, “manages to be both very concise and kind of at arm’s length at the same time, which seems to be interesting for images that are introspective and retrospective.” Knecthel received his BFA and MFA in the ’70s at CalArts, where he was classmates with Thomas Antell, whose work he continues to admire to this day.

Thomas Antell, The Ownership of a Plank, 2022. Photo: Daniel McCullough. Thomas and I were in Emerson Woelffer’s painting class, where he introduced me to the work of Max Beckmann, who is a lifelong favorite of mine. Thomas’ work, even then, was this very eccentric figuration. It was deliberately ham-fisted and somewhat clumsy in its handling. From Beckmann, he had adopted a very heavy use of black in shading and outlining and giving his figures a chunky substantiality. Thomas is a member of the Ojibwe tribe and now lives on a reservation in Wisconsin. He has kept the strange rough-hewn figuration that I first knew years ago, but it has become much more sophisticated in how he handles it, much more delicate, and much, much stranger. He’s used it to create a narrative about loneliness, alienation and strangeness that is very powerful. It is linked up in his own thinking to narratives about how colonization happened, how the Indians were marginalized and victimized. But the thing is, you don’t need to know that to look at this work. This work creates a weird kind of clown show of figures who seem to be strange and gaudy. And at the same time there’s a deep melancholy running underneath the images. The paintings are often frontal, so they feel like they are taking place in a stage set with everybody facing you, side wings and backdrops, draped curtains. Oftentimes the figures are just round heads that are patterned in a way that is kind of garish decoration—but when you really look at them, they seem to also suggest sores. Faces are very stylized; they are not the faces of real people, but have pointy noses and discs for eyes, with sometimes a strange clown hat that’s often beautifully painted with stripes like a cornucopia that ends in a twist. In this latest series, there’s a very surprising deep space with a far horizon line and a tiny ship or tiny building on the horizon, or a little ripple of white paint that indicates waves. Like Beckmann, he works this vein of figurative imagery that seems very personal and idiosyncratic yet is able to ride between something that seems dreamlike and something that describes our society today. I think this is a real achievement—to get it right in that space between what is deeply private and what is actually an embodiment of something happening to society. Thomas’ work is right in that space.

—As told to Tulsa Kinney

-

From the Editor

May/June Volume 18, issue 5 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,In the early Artillery days, I assigned a writer to critique the films and videos that were showing in the sprawling 2007 MOCA exhibition, “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution.” There were more than 20 films and videos included, mostly viewed on the original, portable black-and-white television sets or small analog monitors with bulky VHS recorders and other archaic equipment. Thick black cords, oversized headphones and extraneous hardware gadgets were in full view, making them part of the dated presentations.

After seeing the massively impressive, exhaustive exhibition (full disclosure: I pretty much skipped over the videos), it dawned on me that I should return and really watch the videos, all of them, in their entirety. The low-budget (or nearly no-budget) production of most of the work provided a window into the then newly discovered medium being used in art—video.

Besides my desire to go back, I thought that others might feel the same way. (Don’t most museumgoers skip watching the entire films at big exhibition shows?) I found myself drawn to the crude videos with the grainy black-and-white closeups of women’s faces and naked body parts—usually the artists themselves—always full-frame. Contemplative observations, confessions, questions, concerns and self-absorption seemed to be a running theme in a lot of the films. But really, could I sit through all of them? Perhaps I should’ve included a rating system when giving the writer his assignment to cover the show.

There doesn’t seem to be much need for help in making those decisions these days. In this Film, Animation & Video issue, we feature six female artists that make it impossible to walk away from their moving image pieces. For one thing, it’s usually the main thing in the exhibition, filling the gallery entirely, not tucked away in a darkened side room. Technology has leaped into a big fast-forward since the days of the “WACK!” show. Although Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme draw on the past for inspiration, their multichannel, multisensory films look very different from the days of the portable black-and-white TVs. But they still talk about the things that are important to them, whether personal, familial, political or emotional, as reported by writer Tara Anne Dalbow. Admittedly, there are new matters to explore 20 years later. For instance, multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld delves into 21st-century concerns, such as “self-image and the filters that augment—or completely change—our appearances,” writes New York contributor Annabel Keenan. Lilienfeld explores our virtual selves, or rather how we present ourselves in the virtual world. Women especially fall victim to the superficiality of social media, even to the point of going to plastic surgeons with their “filtered” double as a model.

In the end, the writer finally turned in his copy on the “WACK!” show, claiming he did as well as one could in the three hours he spent watching the videos and films. He came up with a rating system, and one of the films he watched in its entirety—and claimed to have been “mesmerized” by—was 27 minutes long. Our contemporary tools make the art of creating moving images a much easier process. But the message remains the same, as you will see in these pages.

-

Editor’s Pick: Margaret Lazzari

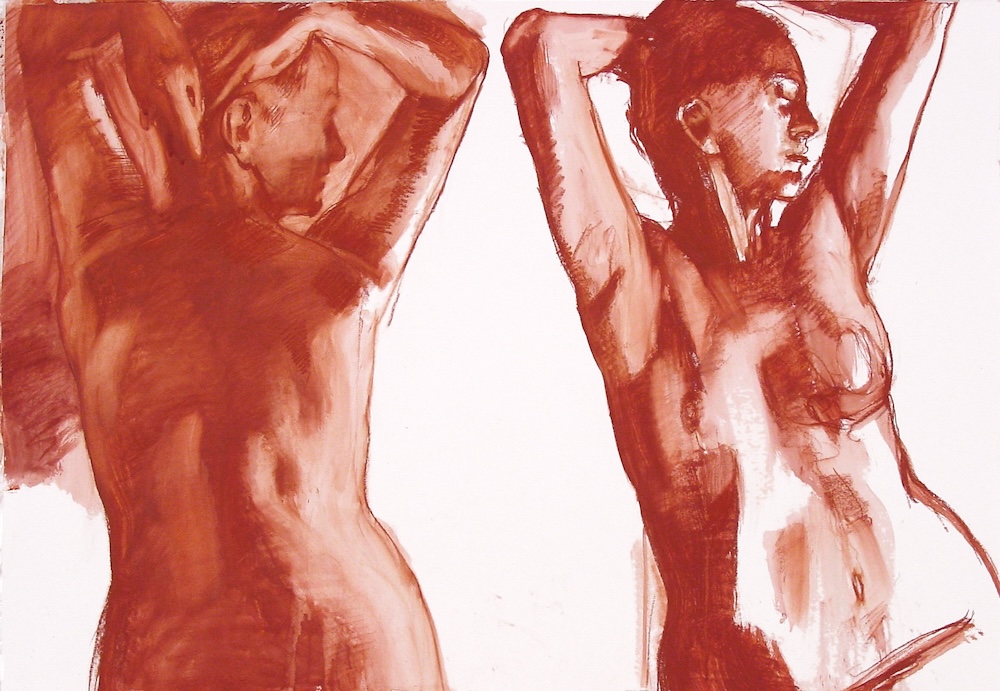

USC Fisher Museum of ArtThe New York Times recently ran an article with the headline “Art Isn’t Supposed to Make You Comfortable”—Margaret Lazzari’s series of works devoted to her traumatic struggle with breast cancer, “The Cancer Series,” fits right into that category. More than 30 works of paintings, drawings and videos created between the years 2003 and 2004—when Lazzari was in treatment—fill the back gallery of the USC Fisher Museum, where the smaller gallery for this intimate show seems the perfect space for these bold and sometimes hard-to-look-at work.

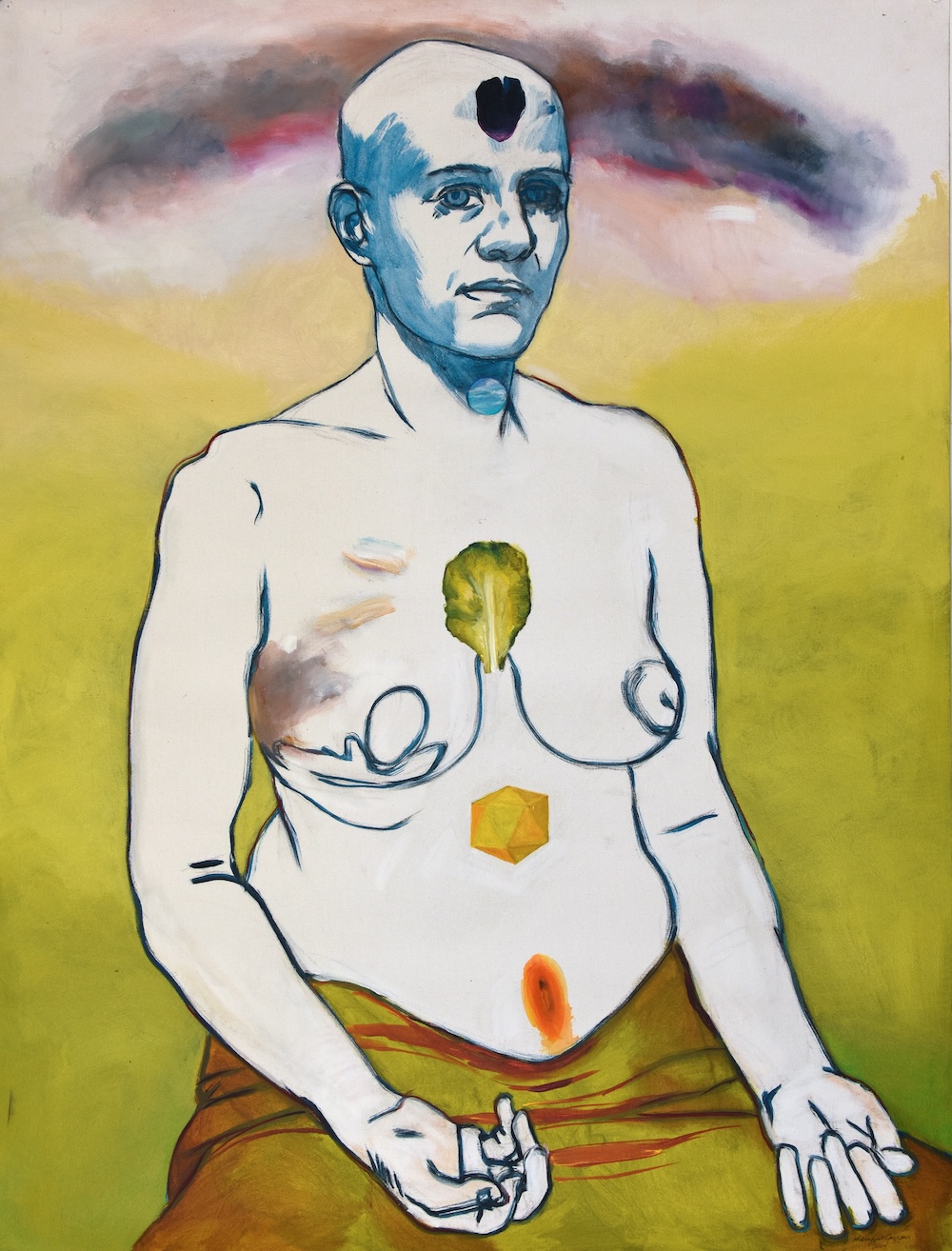

Margaret Lazzari. CHAKRAS. Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 47.5 x 35 inches, 2004 Making a point of exposing her scars from breast surgery, Lazzari doesn’t hold back with this candid look at her experience with cancer. There are three videos—each around two-minutes long, all self-portraits. In one particularly strong video titled Headdress (2004), we see her nude reflection stopping at her breasts, cropped closely within the frame (almost like an accident). Lazarri preens and fake-smiles as she tries on different wigs, hats and scarves for masking her bald head, a result from the chemo treatment. She applies makeup as she tries out different profiles with each new look. This is hard to watch—even though her grooming is somewhat charming and comical—because the scarred breast is always in the frame, as a constant reminder, along with her baldness of the hardship she’s been through. In another animation video, Tumbling (2004), Lazzari’s charcoal drawings of her bald nude figure cascade downward in different stages of repose, intertwining, overlapping and overlaying, eventually obliterating the image sometimes, accompanied with heavy breathing sounds, seemingly in agony. All of a sudden the ominous soundtrack fades into a breezy jazz background music for a cocktail party. Then the screen flashes—for only a second—to Lazarri looking glamorous with a fetching platinum short haircut dressed in a deep-blue, low-cut cocktail dress—but alone, not at a cocktail party.

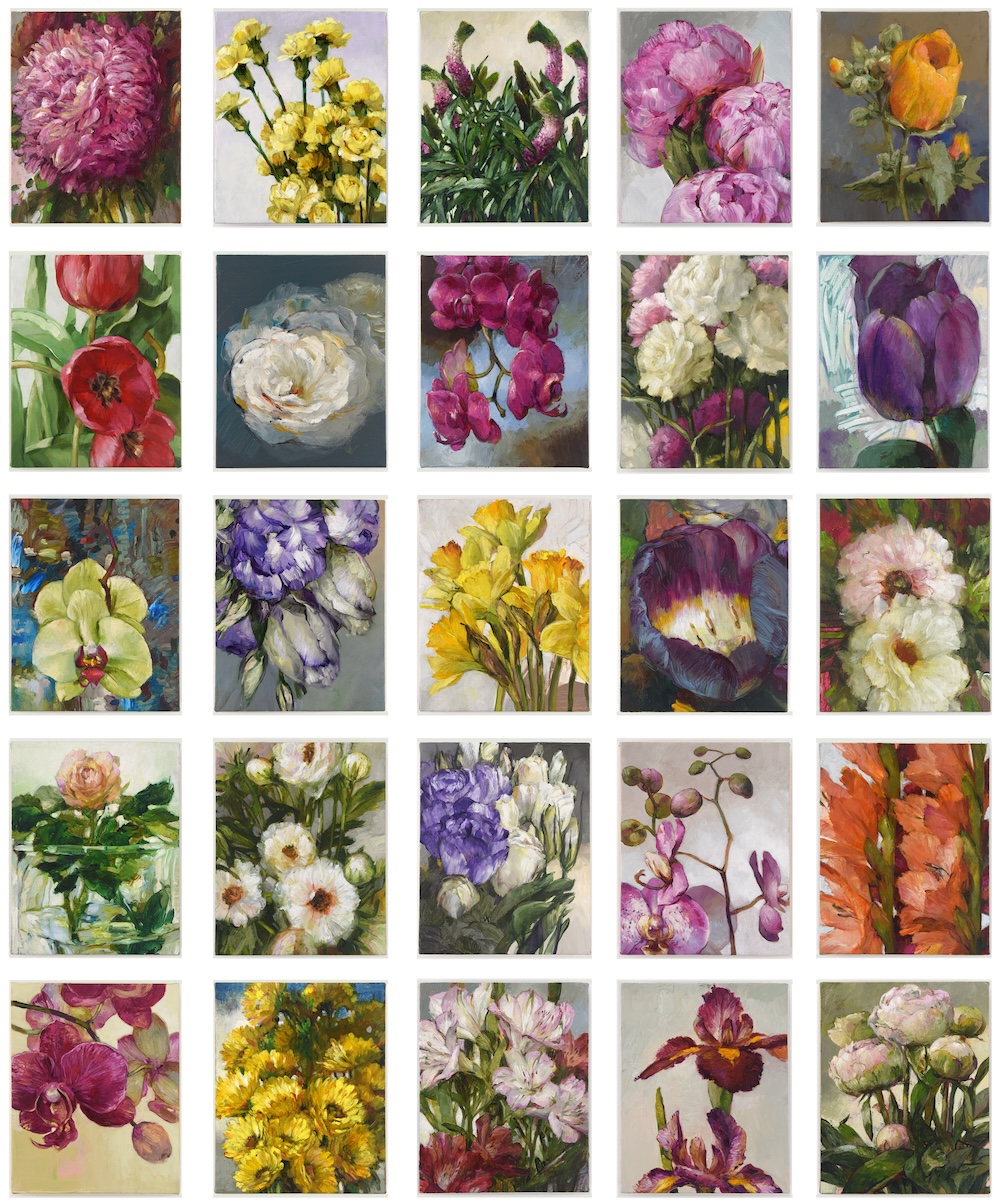

Margaret Lazzari. 25 Flower Paintings from the Get Well Series (ongoing). 2021-2024. Acrylic on Canvas, each is 10 x 8 inches. As installed in Fisher Museum. The gallery is filled with other drawings, all self-portraits, in various stages of her breast surgery. Lazarri does not leave anything to the imagination, exposing the pain and abyss one enters with chemotherapy. One might expect the series to be sympathy-inducing, but the work is so powerful and daring, the viewer is more in awe and empathy. She does, however, provide hope, implied by a grid of 25 same-sized small paintings, all of flowers, filling one wall. This is from the ongoing “Get Well” series (2021–24), depicting all the flowers she received from well-wishers. So, in the midst of all the pain, there is a brightness to the darkness that Lazzari presents in this emotionally charged exhibition, and yes, it makes us uncomfortable. Like art is supposed to do.

Margaret Lazzari: The Cancer Series

USC Fisher Museum of Art

Through May 10, 2024 -

From the Editor

March/April; Volume 18, issue 4 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,I admit to being a Luddite when it comes to preferring a paintbrush to the computer. So, when artists gained access to AI-generating tools, I wasn’t that impressed, nor alarmed. There seemed to be a lot of hoopla and fearmongering about the prospect of such a tool making art … perhaps even more efficiently than humans?

Our Nonhuman issue addresses various approaches that artists take in dealing with the nonhuman, whether it be in physical form or robotics. The Haas Brothers, interviewed by digital columnist Seth Hawkins, embrace AI-generated art and are unapologetic about it: It’s simply a tool, as they put it. So, what’s all the fuss about? Bill Smith, our creative director, ponders the future possibilities of AI, and asks the bottom line—will the collectors buy it? George Legrady talks about working with computer-generated images since the ’80s, so he isn’t so impressed with the hoopla either. On the other side of robots—and the world—Australian Patricia Piccinini’s “creatures” seem more lifelike. Contributor Barbara Morris discusses Piccinini’s hybrid sculptures of the human, animal, natural and artificial—all of which resemble living beings with hair, skin-like surfaces, eyes and mouths. The end results border on the creepy and hideous, yet a sense of a vulnerability emerges, that of an innocent child or animal. They are supernatural and hyper-real, making us wonder if this is what humans will morph into in our continuing evolution.

Or will we become puppets, wooden, void of emotion? Sophie Becker, who is featured on our cover, spoke with Publisher Alex Garner about incorporating ventriloquy in her art and taking the act on the road with her partner and dummy, Jerry Mahoney. Garner also enlightens us with a brief history of the puppets, who were presented as evil, murderous and demonically possessed. The humanlike quality of the ventriloquist’s puppet has always captured our hearts, but scared the living shit out of us too.

This issue does have a sense of doom about it, which, given the theme, was perhaps inevitable. It can be argued that the progress of Artificial Intelligence can be a good thing, right? Think of all the possible scientific breakthroughs. But robotic objects have always aroused suspicion: to be inhuman is to be immoral and uncompassionate. Can society allow AI to make our decisions for us and even tell us what good art is?

It seems to me that people will always be making art, even if they are using AI-generated art programs like Blender or Midjourney. We have a need to create, even if it’s just cooking or planting flowers. One thing this Nonhuman issue made me feel and think about—besides the overall sense of malaise—is what it is to be human, which includes holding a paint brush dipped in gooey oil paint or molding a glob of clay with your bare hands. People still need physical contact. Like Bill Smith says in his article, I don’t think we have anything to worry about … just yet.

-

Mary Woronov: A Survey

West HollywoodMary Woronov, Chelsea Girl, writer, actress and painter, is currently displaying her luscious punk-rock paintings in a Pop-up exhibition at an old Land Rover/Jaguar dealership in West Hollywood. This is a rare opportunity to see this extraordinary survey of her unique painterly style, mostly figurative, vivid canvases—but don’t skip over her smaller psychedelic neon landscapes; they are gems. Her figurative works have a ghoulish, misanthropic overtone to them, like aliens or ominous cartoon creatures. Some fans know the iconic Woronov only through her association with Andy Warhol, but oh, she is so much more.

“Mary Woronov: A Survey” runs through November 30.

9176 Sunset Blvd., West HollywoodSaturday, Nov 18th 4-8pm Meet the artist, who will sign Wake for the Angels: Paintings and Stories and discuss her work.

Upcoming will be screenings from her film career (Eating Raoul, Rock & Roll High School) with Q&A. Dates TBA.Curated by Artist/Gallerists Eric Ernest Johnson + Roy Rogers Oldenkamp

Open Weekend Afternoons and by appointment (323) 875-5657

Metered Parking, parking in Beverly Hills residential until 8pm and fee lot parking. -

From the Editor

November/December 2023; Volume 18, issue 2 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,This issue is a fave of mine. I’ve always loved crafts, especially as a youngster. I taught myself how to sew and embroider, and I made a hooked-rug wall-hanging in my high school art class. I was by far the youngest member of a quilting bee. I even considered becoming a ceramicist when I was an undergraduate. But in my mind, at the time, I didn’t think of those mediums as something to be taken seriously. No notable or major artist worked with those materials. Crafts were reserved for hobbyists—and I wanted to be an artist.

Recently, little by little, these mediums have been showing up in art galleries. Sure, Picasso and Matisse used clay as a medium, but their ceramic pieces were supplemental to their paintings. Ceramics became recognized in the contemporary fine art world with the likes of Ken Price and Betty Woodman—few other artists were working solely with the material. It really hit home when I was visiting the Frieze LA art fair last February in Santa Monica, where crafts were being prominently displayed—and purchased. There were weavings, tapestries, ceramics, embroidery, hooked rugs, you name it—about the only things missing were macramé and candle-making. Works were dangling from ceilings, covering vast wall spaces and crowding gallery cubicles, all in bright colors, messy glazes, wrinkly fabrics and unexpectedly lascivious scenarios. It was a cacophony of texture in 3D. These relatively new-to-the-art-world mediums made everything else look drab and passé.

When there’s an explosion of new art forms, one wonders if history will record it as an art movement. What caused this new attitude toward crafts, once considered the lowest of art forms found in thrift shops and beachside galleries alongside thrift-wood sculptures? Are artists rebelling against high art and the attitudes that go with it? What caused this quiet revolution in the art world?

Several theories might answer this question for our future history books. Four artists featured in our Crafts & Utility issue have different reasons for choosing their medium. Melissa Joseph, interviewed by New York contributor Annabel Keenan, uses felting to address broader social issues such as gendered labor and identity. Contributor George Melrod talks with Diedrick Brackens about his weaving works; Brackens identifies as a “weaver” and says that working in this medium is his “inheritance,” a medium that he feels has been disregarded in the art world. Sal Salandra, on the other hand, practiced needlework when he was a hairdresser, to pass time perhaps, creating flowers and cute dogs. He eventually gave up the dogs and flowers for more provocative subject matter. His beautiful new book, Iron Halo, is reviewed by Tucker Neel. Lastly, Ahree Lee’s weavings morphed from her video works and computer-related algorithms—the thinking behind both is not so dissimilar, as she tells William Moreno.

I, for one, am thrilled to see this new genre in today’s art world. The tactile freshness of these mediums feels innovative in their use and intention. It all makes me want to dust off my sewing machine—and make some art.

-

PEER REVIEW

Matthew Rosenquist on Pat PhillipsRaised in and around Washington DC, with two degrees in painting, Matthew Rosenquist now makes sculptures, albeit with some paint applied. How did that happen? I ask him. After grad school in the South, he took an entry-level job at the Smithsonian with duties that drew him into the woodshop department: He was making simple tables and chairs and realized he liked working with wood—or more specifically, with his hands.

When Rosenquist moved to New York he still considered himself a painter and continued to show his art while working in cabinet shops. The eureka moment to become a sculptor occurred when he moved to Los Angeles in 2010. He sheepishly admits that while taking morning walks with his dog along the Arroyo he found himself dumpster-diving in the numerous trash receptacles. On one such walk he found a “disgusting, dirty Barbie doll” that he brought back to his studio. A 4 x 6-inch piece of wood was staring at him and he began carving into it, using the doll as a model. Now his repertoire of roughly carved wood sculptures includes vintage television sets, dogs, aerial pieces, figures holding smartphones (all shapes and sizes) and lots of cars and vans from the ’70s and ’80s. This November, Rosenquist will have a solo show of his wooden vans and TVs in Tokyo. He was excited to talk about a show he saw this past spring at M+B in West Hollywood.

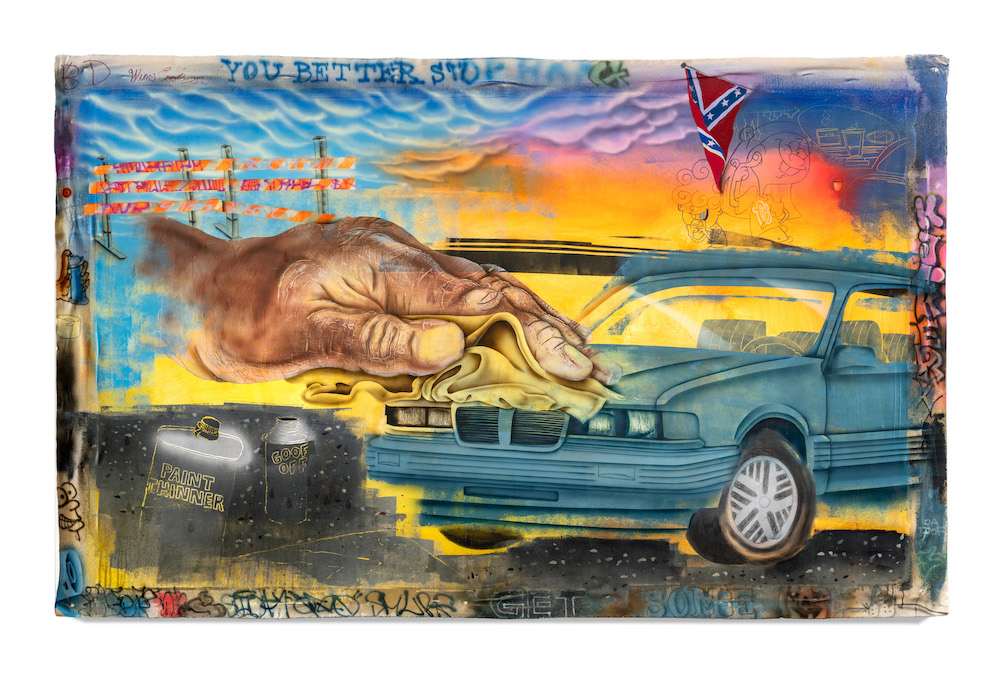

Pat Phillips found my work on Instagram and was really into it; instantly we were simpatico. A lot of his references relate to his memories of growing up in the South in the ’90s and early 2000s, not so dissimilar to my upbringing. I love his depictions of cars, sneakers and especially how his cartoony drawings appear within his paintings; he draws very well. When I saw his exhibition “Strange Suburb,” there was one painting that stood out for me titled You Better Stop Hangin’ Out With Them White Bois. A giant hand with a rag is seemingly wiping down an old Pontiac Grand Am, the same model my aunt had growing up, of which I have fond memories, although it’s an awkward looking ’80s car, not real good-looking, but kinda cool as well. It’s a powerful painting where Phillips visually packs everything in with all of these symbolic smaller components (rebel flag, barricade points, graffiti, a can of paint thinner, Goof Off—a paint remover). Elsewhere in the show is a neon text wall piece: “POOR OLE NIGGA THINKS IT’S A CADDY”—a colloquial acronym for Pontiac. Where the hand might look like it’s polishing the car, actually there’s a much larger message. Phillips is addressing the racial and social inequalities of being Black and growing up in Louisiana. The large hand in the painting is trying to erase his tarnished childhood memories rife with the injustices of being Black in America.

—As told to Tulsa Kinney

Pat Phillips, You Better Stop Hangin’ Out With Them White Bois, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and M+B, Los Angeles. -

From the Editor

September/October 2023; Volume 18, issue 1

Dear Reader,

Seventeen years—that’s a long time. Most relationships don’t last that long. That number has now outlived all my other jobs; I’m referring to my relationship with Artillery. I started this magazine with my late husband in 2006, who warned me: Once you begin, you can’t go back. Boy, was he right about that. I can’t call in sick, never take a vacation or even a personal day during deadline. This is one of the most committed relationships in my life.

Even though it’s a huge responsibility, like any relationship, things can change throughout the years. Hopefully one improves with age, develops other new relationships, changes one’s look—maybe even get a facelift? (We are in Hollywood!) Well, it seemed like it was time for that makeover, and you’ve probably noticed right away that this editor’s letter looks different. Keep turning the pages (after you’ve read my letter!) and you’ll see our splendid new redesign throughout the entire magazine. Creative Director Bill Smith headed the new look and did a great job, along with designer Dave Shulman. They put in long hours in collaboration with Publisher Alex Garner and me. We’ve changed our body text, hopefully for more legibility, and added some new subtle bells and whistles. We’ve expanded our layouts to highlight more visuals—we are an art magazine, after all.

Besides the new look, we’ve added a new column, “Peer Review,” which looks at the practices of two artists. In each issue, a contributor will invite an artist whose work they admire to talk about the work of another artist, one of their peers, that they are drawn to. For this issue, Alex asked New York–based artist Fin Simonetti to participate, and she chose Ambera Wellmann, who recently had a show in Turin. Be sure to check out Simonetti’s impressive marble sculptures and stained-glass works in an upcoming show in Los Angeles this fall.

Our theme, Systems of Power, features artists whose works are politically and socially engaging, questioning and challenging the system. Can art change anything? This has been an ongoing discussion in Artillery since day one, and by now it has almost become a rhetorical question. New contributor Cat Kron talks with Martine Syms about her autobiographical films. Longtime contributor Christopher Michno writes about artists who deal with the environment, specifically climate change. East Coast reviewer Sarah Sargent gets her hands on the powerful book Redaction, co-authored by Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts, both of whom are prepared to take on the systemic racism in our penal system. And Bianca Collins talks with Indigenous artist Mercedes Dorame about her latest installation at the Getty Center.

We hope you’ll enjoy our September issue as we celebrate our 17th anniversary, with a new look and our stalwart regulars mixed in with new writers and reviewers. It seems hard to believe we’ve been around this long, but I guess some things never grow old.

-

From the Editor

July/August 2023; Volume 17, issue 6 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,Reading wasn’t a top priority in our family; I don’t think I was ever read to as a child. It wasn’t as if literature was banned in our house, but the walls weren’t exactly lined with bookshelves. The preschool in our tiny town was held at the local library, and that was my first real introduction to books and being read to. I loved the smells, the colorful spines and the quietness of the library. It was such a relaxing atmosphere that I couldn’t wait to visit it, and it was there that I fell in love with the world of reading.

In elementary school we had the Book Mobile (as there was only the High School Library). A van would come around the school on certain days of the month, and we could check out books. It was such a delight to walk around in its cramped quarters—and the driver was a little creepy. I looked forward to every visit with my finished book in hand, ready for another.

I can’t really recall what books I read, but I’m sure my selection wasn’t very sophisticated, unlike some of my childhood friends that bragged about reading the likes of Ulysses when they were nine years old. In high school my tastes began to advance. My friends were often smarter than I was, and they would recommend books. One book that I remember vividly—and which was responsible for really getting me hooked on reading—was In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. Since we didn’t live that far from Kansas, where the infamous Clutter family murder took place, the proximity added to the mystique and thrill. Every chance I got I would open that book. A few times I got in trouble for being lazy (translation: lying around reading) and was told to get off my duff, set the table, or vacuum the rug. But that book made that horrific murder come alive for me. I would be terrified and couldn’t read at night for fear it might give me nightmares.

When I left home, my first husband, an avid reader and local pot dealer, turned me on to The Beats, Philip Roth, John Cheever and Charles Bukowski—of whom I was especially fond. His work was so honest and hilariously ribald. It was inspiring to find something that I really could sink my teeth into.

As my husbands accumulated, so did my personal library. I ended up working fulltime in the cataloging department at the Tulsa University Library. I loved that job and found the two main women catalogers that I worked for to be delightfully enigmatic. I was fascinated with their job and hated to interrupt them as they were always so enrapt, sitting in their cubby holes, thumbing through the pages, taking notes. They were so smart and hip and worldly—and well-read.

I’m still a diehard fiction fan and always have a book going. I couldn’t imagine a world without reading. Every summer we publish a reading issue, just like other publications do with their recommendations. Here are ours, mainly focusing on art. We like to include films too, such as the documentary on Thomas Kinkade reviewed here by Doug Harvey. Kinkade: alcoholic misanthrope, painter of light. How irresistible is that?

No matter what your fare, we think we have an eclectic selection to consider. And don’t let anyone tell you that you’re lazy. Now get off your butt and go visit a library or buy a book—before they actually do get banned.

-

From the Editor

May/June 2023; Volume 17, issue 4 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,“Art about art is elitist,” my boyfriend in grad school used to tell me. But if that was the case we wouldn’t have AbEx, Minimalism and maybe even Conceptualism. I got it though: The art world with its various trends and movements could seem precious and pretentious. Even so, I did love painting for painting’s sake. Some would say I excelled in the non-representational art form. There’s nothing like a great abstract painting. I’d kill to own a Brice Marden.

But what about all the injustice and malaise we see today; can we really just make art that is only about art? As artists, isn’t it our duty to be addressing larger concerns? Our “Public Display” theme in this issue includes artists who consider their community and the world around them—recognizing the importance of engaging with their surroundings, they want to give something back.

Some art venues fall into the category of nonprofit organizations, which, thankfully, get the help of residents who serve on their boards and grants allotted from municipal funds. One such place is the community-building organization in Leimert Park, conceptualized by South LA’s own Mark Bradford, Art + Practice. Alexia Lewis catches up with the A+P team who run programs for teens and award several scholarships, among many other altruistic endeavors. Regular online columnist Lauren Guilford interviews Jessica Taylor Bellamy, whose work deals with LA’s unique eco-phenomenology. And our cover artist is San

Francisco–based Andy Freeberg, featured and written about by regular contributor William Moreno. Freeberg delves into the commercial aspect of the art world and exposes the machinations of that milieu—unsurprisingly it isn’t very different from any other free-enterprise world.I’ve often felt that Artillery plays a role in serving our LA arts community; at least we try like hell to. And LA gives back in buckets, especially our loyal supporters. With that in mind, I’d like to announce an important addition to our staff: our new publisher, Alex Garner. She hails from New York City where she worked at Artforum for several years, and MoMA—a little New York in our mag couldn’t hurt anyone, right? Alex knows the ins and outs of the art world and recognizes its complexities—how small it can be, yet expansive at the same time. The LA arts community is where Artillery’s heart really is and Alex is aware of the significance of our city as an art-world center, equal to New York. (Just look at all the New York galleries moving here!)

Exciting new things are in store for Artillery with Alex on board. She already has an online art column in our weekly newsletter, The Publisher’s Eye. I couldn’t be happier to begin our collaboration, putting our heads together to better serve the LA art scene. We know how important that is, and how important Artillery is to LA.

It’s hard to believe that in the 16 years I’ve run this publication (with the help of our loyal contributors and employees), things just keep getting better. Owning an art publication may seem provincial, even elitist, but I can’t help but think there’s some good that comes out of it. Art for art’s sake, anyone? We’ll take our chances.

-

From the Editor

March-April 2023; Volume 17, issue 4 Dear Reader,

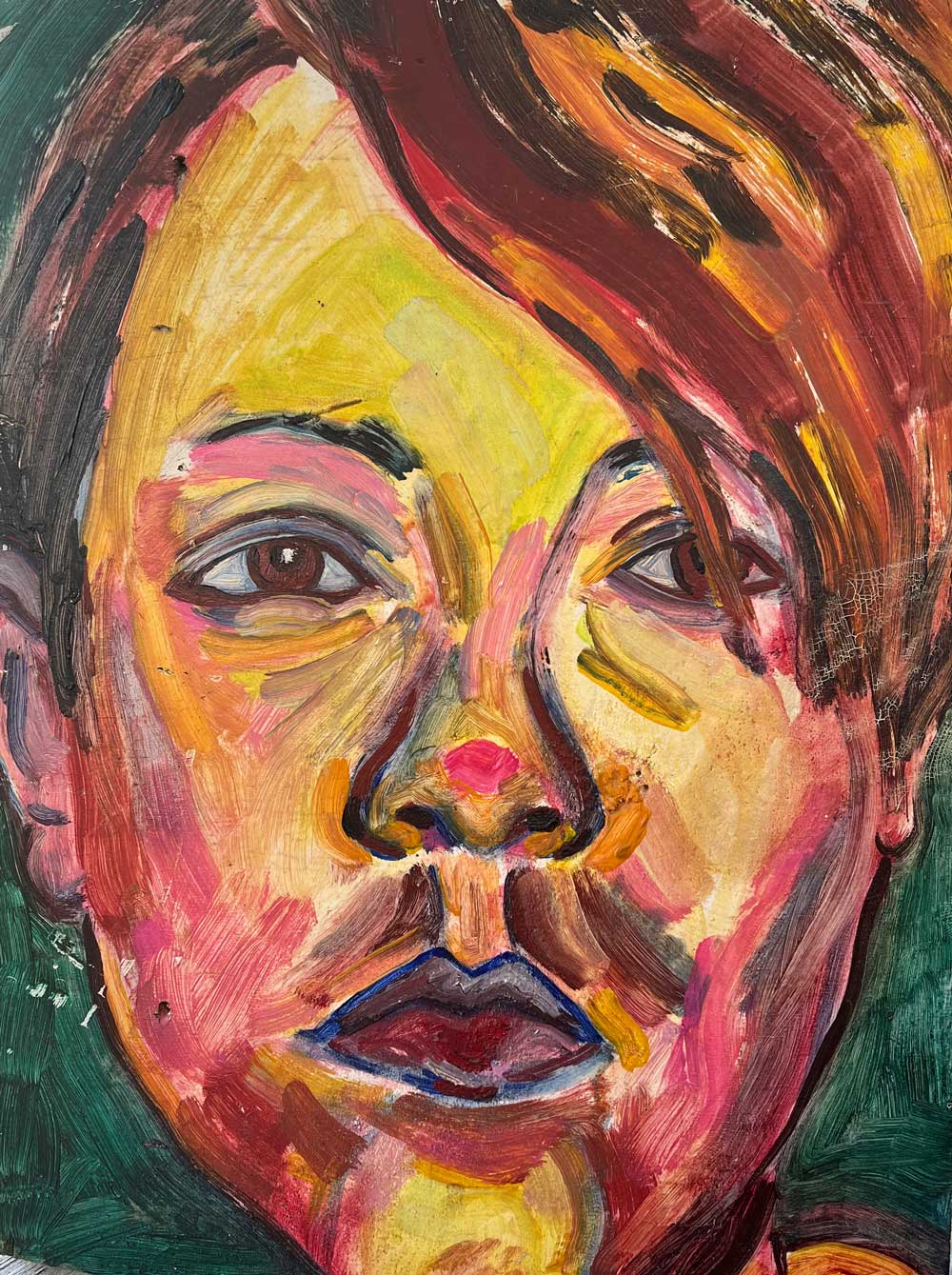

Dear Reader,As long as there are people, there will be portraits. Face it—no pun intended—people are attracted to people. We like to look at ourselves; we like to people-watch; we gaze into our lover’s eyes. Our faces are unique and fascinating: they are who we are.

As an artist, I was drawn to portraiture with my painting and photography. Once I embarked on a project to capture all of my friends’ faces (I can’t begin to tell you how many paintings that produced!). I photographed them, then painted only their faces onto an actual-size piece of found wood. Afterwards, I gave my friends their portraits—most of them tell me they still have theirs. I did this project for many reasons, but mainly to explore the mysteries of physiognomy—to discover how every face is so individual and reveals (or possibly disguises) that person’s personality.

An artist can get lost in the process of painting a face. Sometimes all it takes is the way the subject’s hair curls, a slight upturn of the smile, or the type of spectacles they wear that defines their being. Often a quick flick of the brush on a shadow or highlight is all that’s needed. Something so minute might be the ticket, then it’s done.

Each artist we feature here has their own unique approach to portraiture. Amir H. Fallah’s paintings involve complex narratives that address cultural boundaries. In his current body of work most of the faces are covered. Fallah’s elaborate figurative paintings are not drawn from actual people he knows, but from imagery found on the internet.

On our cover is Helen Chung’s painting of LA artist Senon Willams. Writer/critic Ezrha Jean Black sits down with Chung to discuss anatomy and the intimacy involved with the act of painting the sitter—which is Chung’s preferred method.

Luis Sahagun’s portraits employ traditional Meso-American healing rituals. His role as the artist is that of a spiritual consultant who examines the person he may doing a portrait of and what their ailments might be, often the result of social stresses. Sahagun will then apply the necessary materials that reflect the broken parts of that person’s being. In one instance, he does a self-portrait of when he experienced racism at college. David S. Rubin interviews the Mexican-American Chicago-based artist.

Henry Taylor is a storyteller with his portraits, written by Donnell Alexander. But don’t call him a portraitist. That was stressed in the opening press preview. That could also be said of many artists who are known for their portraits. Though don’t all portraits tell a story? Once you put a face on it, you’ve got a story—a person, a life.

If one visits the art galleries these days one does find that there’s an uptick in portraiture. Maybe that’s a sign that we are still human, and in these days of AI, that’s something to hold onto dearly.

-

From the Editor

January-February, 2023; Volume 17, issue 3 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,My social media intern recently sent me a text with an unmistakable degree of urgency. She stated that Chance the Rapper was trying to get in touch with me by Instagram message. “Who?” I replied. My assistant, being of the millennial generation, was not at all surprised by my ignorance. I think she even anticipated my dumbfounded reaction, hence her urgency. “I don’t think you understand,” she said, and proceeded to explain the relevance of the young rapper and how remarkable it was for him to actually be reaching out to us on our Artillery Instagram—let alone that he is a follower. Of course, an introduction was immediately made.

What on earth would a noteworthy musician such as Chance want with me, an editor of an art magazine? My interest was piqued. After informing a few of my younger friends, it was confirmed: It was extraordinary that this massively popular rapper was reaching out to me.

My assistant made the e-intro and soon we were united, digitally; there was to be a Zoom meeting. I included my assistant in the thread and the Chance team joined in on the Zoom call, about six of us in all. A few faces made an appearance, but most of the participants kept their video off. We were all waiting for Chance. I was nervous by now, and still couldn’t imagine what this meeting was all about. Soon he appeared, but not in the flesh (as it were). There was a big letter C that pulsated in rhythm to his speaking voice, like the all-powerful Oz, although Chance was soft-spoken, thoughtful and polite.

I was informed that Chance has been collaborating with the fine-art world on a specific art project. He was working with the Black Diaspora and wanted more inclusion of these important artists. Being from Chicago, and a regular patron of the arts, Chance couldn’t help but notice the lack of Black artists in the art world and the elitism that exists in the fine-art world. Unfortunately, I found his observations to be quite accurate.

Chance would be in LA in September, doing another collaboration with artist Mia Lee (whose portrait of Chance is on our cover), at the Museum of Contemporary Art. I contacted writer and hip-hop aficionado Donnell Alexander—who I’ve known for years, since the old LA Weekly days—and he was eager to do something on Chance, for whom he has great respect.

Chance is very keen on working with African artists and this project will end up in West Africa in the New Year. It so happened that a new gallery in West Hollywood, dedicated to exhibiting African artists, caught the eye of writer Donasia Tillery, who appears in the issue with a Zoom interview of African art dealer Adenrele Sonariwo from Lagos. Annabel Keenan, our New York contributor, writes about New York–based Trinidadian-American Allana Clarke’s work, which deals with Black attitudes to hairstyle. All this came together to present features on the Black Diaspora Emerging in the art world.

I love starting off the New Year with fresh new content and a rapper on the cover. It’s nice to mix things up a bit. Isn’t that what art is supposed to be all about? The art world is constantly changing, just keeping up with the world. And Artillery is right there with it. Happy New Year art lovers!

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,