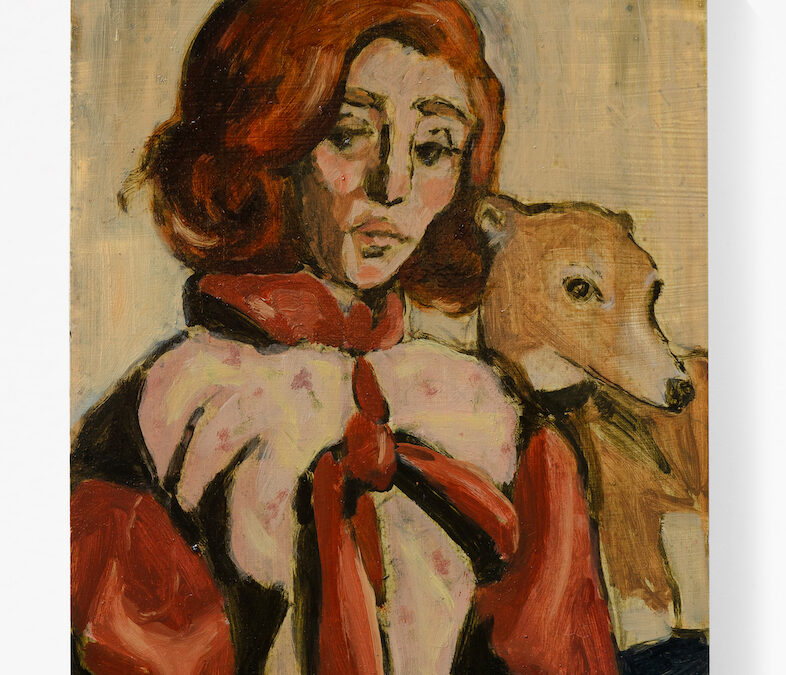

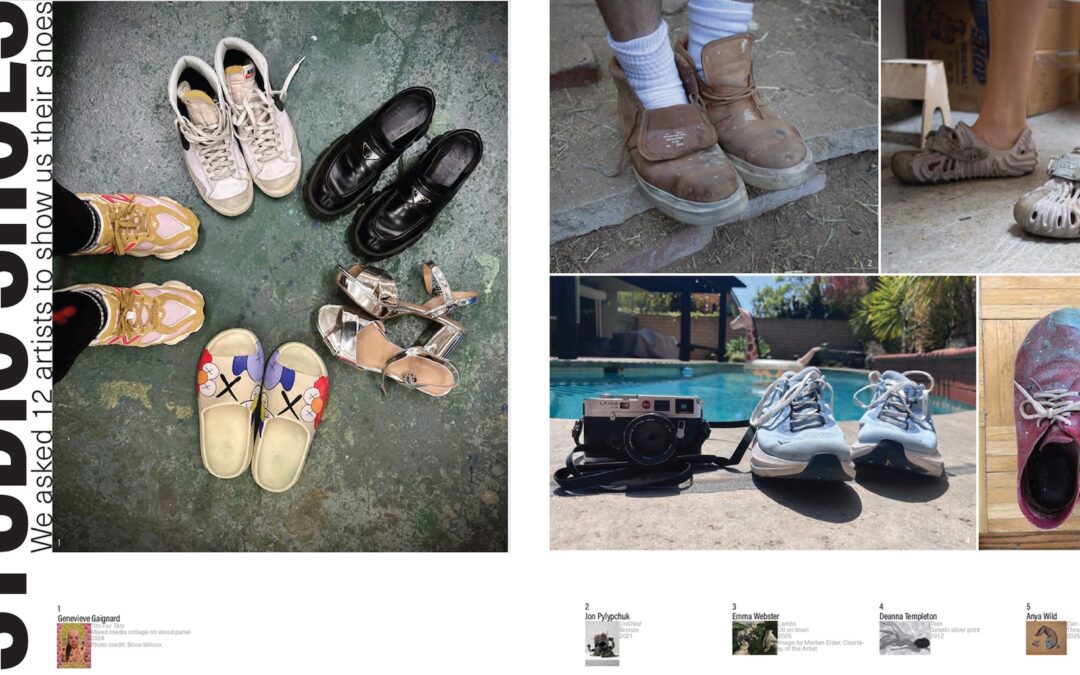

Why do you collect art? Because I can’t not. Art keeps me awake, thinking, and alive. It’s a rush for me. The emotions it evokes for me are some of the most visceral feelings I have experienced. When a piece stirs something in me, curiosity, joy, or even discomfort,...