Doubtless you’ve seen the billboards: the Immersive Van Gogh exhibit has shown in cities across North America, and now it’s Los Angeles’ turn. It’s Time To Gogh! commands the sign, and I oblige, stepping into the old Amoeba building on Sunset Boulevard, which will serve as the event space for the duration of its local run.

I pass through security and walk into the dark hallway that begins the “immersive experience.” Overhead, a voice actor murmurs lines from Vincent Van Gogh’s letters. This hallway opens onto a tunnel of empty gilt frames that ends at the main foyer, which has a mural of the Hollywood sign painted in the manner of Van Gogh. The voice actor is replaced by classical strings covers of Lana Del Rey’s “Video Games.” FIND BEAUTY EVERYWHERE is scrawled on one of the promotional leaflets.

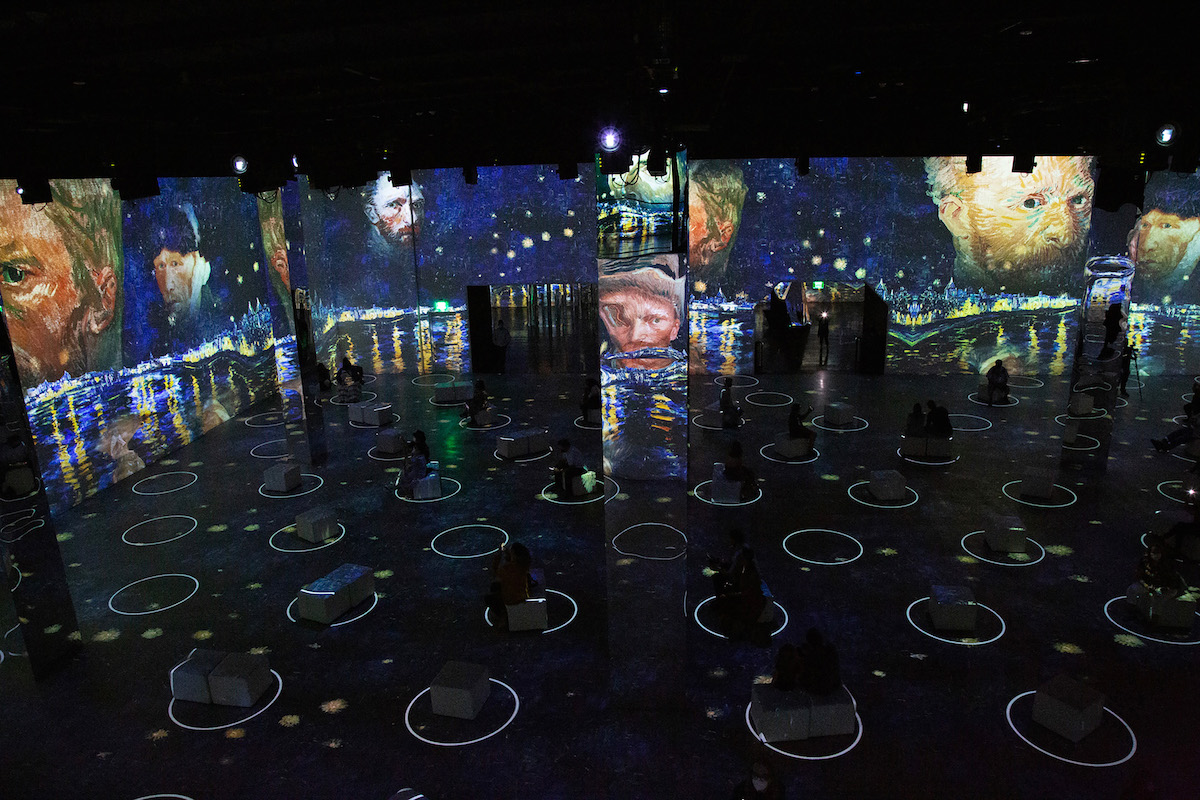

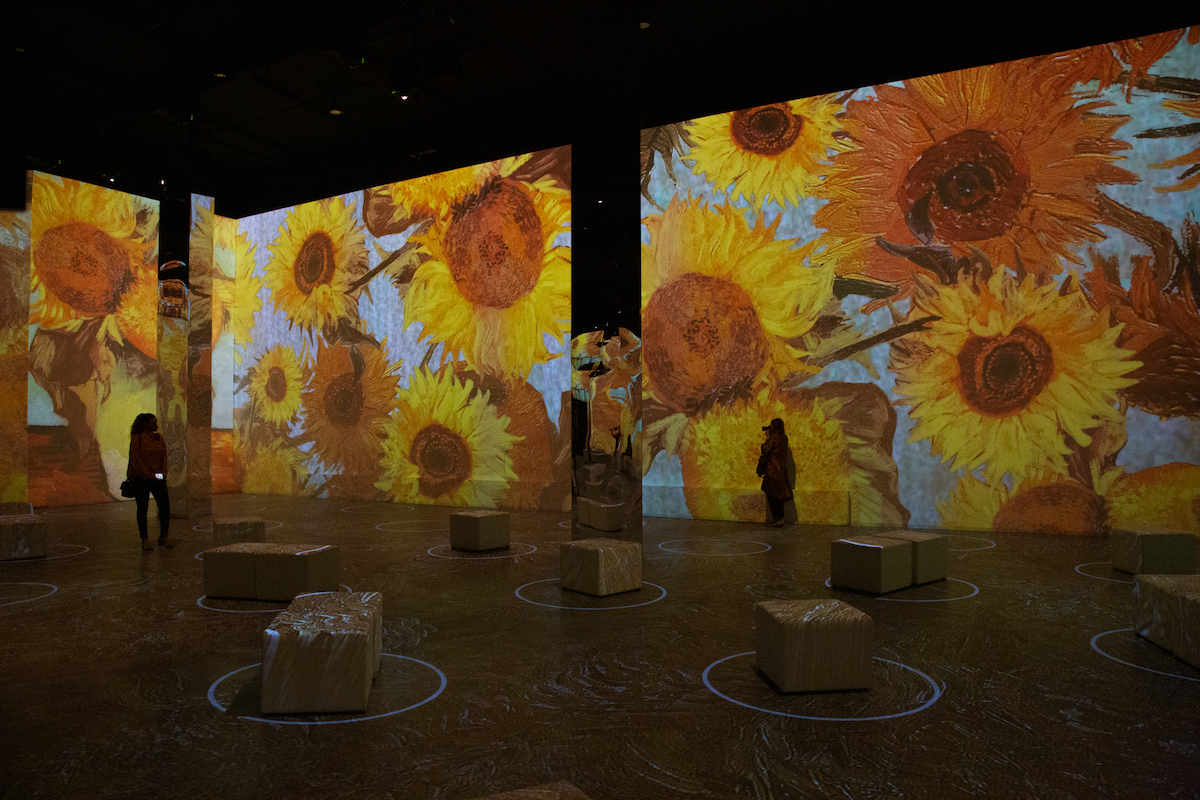

The foyer serves as another hallway, and I follow the crowd to the projection rooms. With the lights on, it would be like standing inside an enormous blank cube. Now, however, the darkness is broken by projections of Van Gogh’s paintings. Heavy bass electronica thrums through the air, while farmland and flowers flow across the walls as if they painted themselves. The animated autonomy of Van Gogh’s works seems strangely fitting.

The first time I remember seeing a Van Gogh, I was an elementary school tot. My teacher wheeled out the projector and cast Starry Night onto the wall. I can still feel the nubby carpet under my hands when I remember this, how it is like the texture of the paint. It seems strange that a painter who found God in the world would have his work transformed once again into that least material of mediums—into light.

It’s impossible to know the first time most people saw his vision of the night sky over Saint Remy, though almost certainly it wasn’t the painting in New York City, hanging on MoMA’s 5th floor. Most likely it was a replication of the image on a poster, a phone case, fridge magnets, backpack or bed sheets, and now this “immersive experience.” Van Gogh reportedly painted many of his works through windows; the replications are now like thousands of miniature windows on his actual paintings, wherever they may really be housed.

I notice a sign near the bathroom advertising an app that allows you to write a letter to Van Gogh and receive one in return, inspired by his lifelong conversation with his brother Theo. “Hi Vincent,” I type, “How’s the asylum?” The loading wheel spins, and a moment later the bot replies, “My painting goes well, despite my worsening circumstances…”

The sense of the prophetic is too strong about his life to have any other relation to it. Each brush stroke brings him a step closer to his death, to the 7mm revolver in the wheatfield. I watch Bedroom at Arles dissolve into another wheatfield painting; Edith Piaf’s “Je Ne Regrette Rien” thunders through the speakers. He suffered exactly as he needed to so that we can experience his life after death, his pervasiveness in pop culture, his penetration into the deepest, oldest corridors of memory. A painted bird drifts against blue walls that were once the painted sky of Arles. Across the world, his work and his words continue to swirl forward in countless repetitions like snow blowing through an open door.

Still, it’s nice to sit in the middle of the floor, as you’re encouraged to, and just look around. The room is filled with families, couples and young children with benches for people who might not have the flexibility to stand up and sit down again. “Irises” floods the wall, and the blue light of the painting washes upon the veined hands of an older woman, sitting quietly, holding her walker. Thankfully, the entire thing is rather hard to take a photo of—the projections are too large to capture anyway and the projections are a little grainy. Instead we sit and look. The whole video lasts about an hour and is on a continuous loop, but you can stay as long as you want.

It is no small irony that we can’t avoid the figure of Van Gogh as the archetypal impoverished artist. The lines of the Bedroom at Arles start to take shape: the bed frame emerges out of thin air along with the chair and the boots, then color splashes into it, and the famous painting looms on all sides; and his legacy seems suddenly, painfully inescapable.