Maggie West took over a large, dark space somewhere north of Frogtown last week and filled it with massive images of flowers, pulsating time-lapse photographed in UV light. The colors have weird harmonies: bad-acid Disney-villain purples and magentas, alien and dreamy but it is all more precise than any dream should be. In a word: it works, this immersive video installation.

No part of it is an accident. “Eternal Garden” is not the kind of art where you lay out the canvas and make a move, then make another based on what you now see, then improvise the next and then the next. Maggie had to sit in her studio with plants, lights and cameras and know that eventually the pictures she was making would be on this particular screen in this specific big black room—it doesn’t work any other way: the piece relies on its precision—and seeing that precision at scale—for its effect. That’s what makes it more than decorative. The art would not only not work without the large and expensive machinery provided by the large company that owns it and the space, it could not even have been thought up without it: the piece is not itself otherwise. Before making the piece, Maggie made a deal. She told the company she would make an installation and it would show off the quality of the technology. She’s good at this sort of thing—and not ashamed.

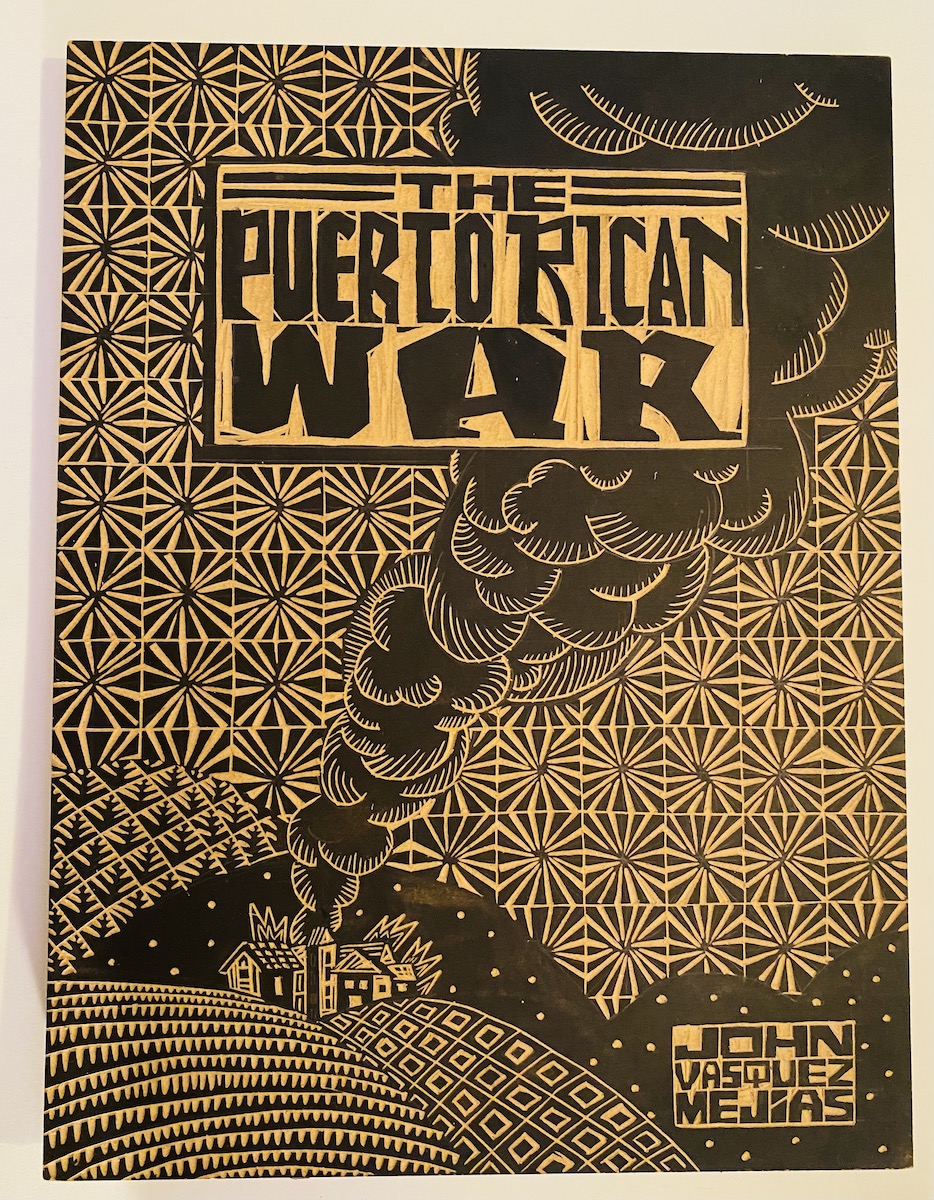

Simultaneously, on the other end of the country, the Instituto de Subcultura in San Juan, Puerto Rico is presenting “No Moral or Legal Authority,” woodcuts from John Mejias’ Puerto Rican War book. It is everything “Eternal Garden” is not: direct, low-tech, blatantly political, black and white, small. And wholly independently produced: the project began during the Obama administration, with no publisher, no gallery and no plan. Pieces of wood were going to get cut, over a span of years, into an intricate, jostling, chaotic and mutli-patterned re-telling of the story of an obscure conflict that even the visitors in San Juan weren’t taught about in school. And if nobody cared at the end? Oh well, John has been self-publishing for years. It turns out this time that they do care—post-colonial problems are on even collectors’ minds these days. But that is an accident. This piece didn’t expect the audience it got.

John Mejias, “No Moral or Legal Authority” woodcut

Both of these very different works deserve to exist and do things art should be doing: it is good to be reminded of the strangeness behind the beautiful growing world all around us, and it is good to find out about a real-but-failed revolution in our country from someone with noir-caper storytelling instincts and an eye for the off-beat—but they also both involve their artists in different gambles.

It is a gamble for John to sit down and make art unsure if anyone cares, and it is a gamble for Maggie to decide to make art that won’t exist unless you first make someone care. The first gamble is earnest, unassuming, self-sufficient, it doesn’t care what you think; the second gamble is clever, charming, sociable, shrewd—it will be loved or it will not exist. Neither artist is rich, and neither was sure that any of this would be worth it.

They are different in other ways: John’s piece is a book: something that sits quietly in private spaces and only is fully what it is meant to be when you pick it up in a quiet moment and decide, on a random day, to meet it more than halfway. Maggie’s piece makes a party: one night only, you could go see it without seeing all the people who want to see it, silhouetted also. You have to get into a car and out again, and then decide how long to linger, drinking, in the dark to make your trip worthwhile.

This art and these artists both knock on our door, but they’re applying for different jobs—they are different, but not competing. Everyone needs the truth, well told, and everyone loves dazzle with something worth dwelling on at the center.

There’s a lie in the middle of how we’re taught about art—that this or that captures the spirit of the age, and that the last thing is the throwback and the next thing is progress. Are we, any of us, a homogeny? We are not. Does any one of us need only one thing? No. Does art have something better to do than give us—humans—the various things we need? It doesn’t.

There’s a fear of scarcity somewhere at the bottom somewhere—that more of this means less of that. In reality, we all need everything.