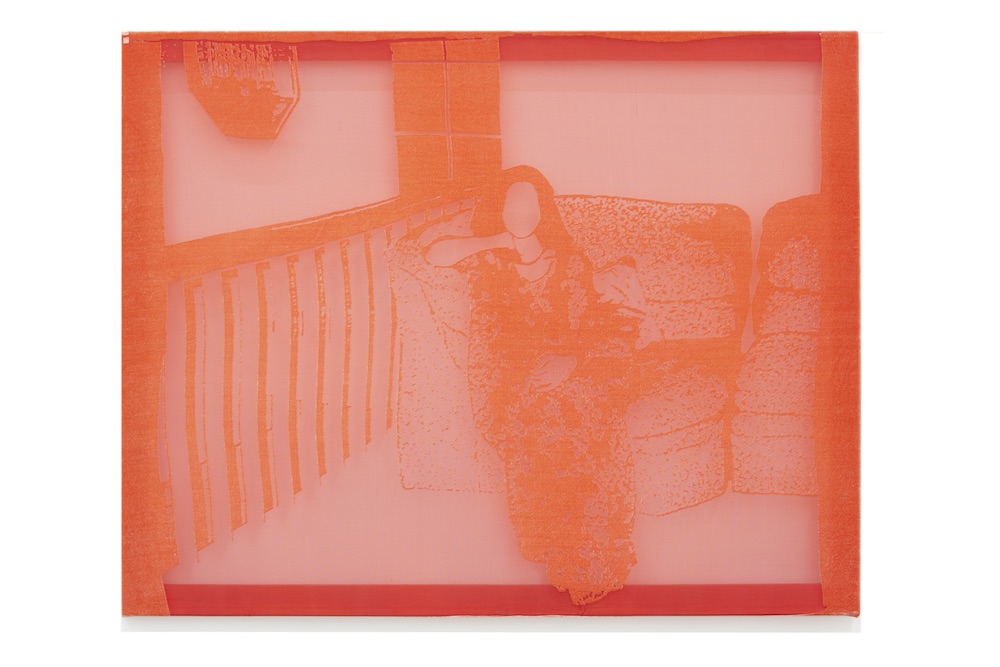

If one wanted to be very art historical about it, Math Bass’ work resembles Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers (1875) with its beautiful detritus and bones and dust and longing bodies and skin-as-paint-as-floor and new life emerging from every crevice. The...