Your cart is currently empty!

James Welling’s “Choreograph” Review of the Photographer’s Recent Book

I got to know James Welling over a decade ago when he invited me to teach a graduate seminar in the history of photography at UCLA’s Broad School of the Arts, where he was the director of the photography program. His own photography was a mystery to me then, as it still is today. I don’t mean that I was confused by his work or had reservations about it. On the contrary, I was dazzled by the intelligence and originality of the art he was producing in a medium so often undermined by its commercial and reportorial uses. A new book of his just published this year, titled Choreograph, is devoted to a single project done over the last six years.

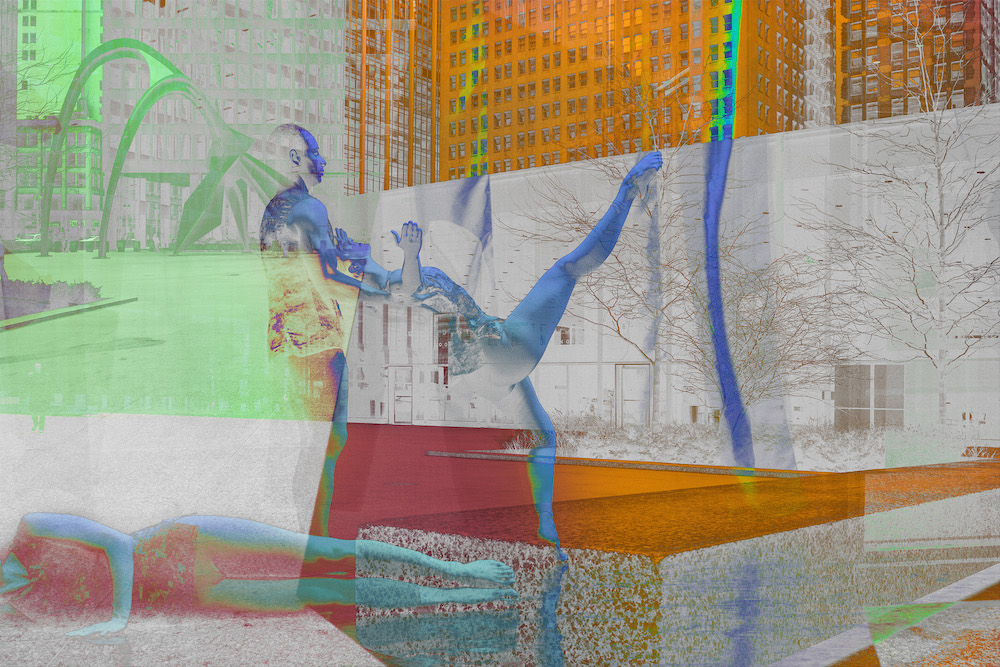

The image you see here is from this latest project of Welling’s. The image is at first, characteristically, confusing. Welling doesn’t condescend to the viewer by making images easily understood. The composition is blocked out in a woosh of colors—soaring buildings that are orange, a garden in the bleak white of winter. In center stage, two dancers dissolve into a motion blur performing a Merce Cunningham “Event” Welling photographed in 2015. Welling’s goal is not to confuse us but to hold our attention in this medium we are used to understanding at a glimpse.

The series is titled “Choreograph” because dancers are the anchor of the imagery, the human subject to which our eye goes instinctively in any photograph. The placement of the dancers at the center of this image compels us to start there and work our way out to the edges. One way the visual arts can help viewers find their way in compound, complex compositions like this is through a kind of formalism, a reciprocity of shapes. In this image, the female dancer’s right leg looping up from her torso mimics the abstract iron shapes in green looping down toward her partner. Those iron curves anchor the image in the Chicago Loop neighborhood where this Calder sculpture is found.

Welling begins each composition with a selection of photographs he has made and plans to combine into a new composition. Once he has decided on the composition, he reduces the parts to black and white and then begins adding color to various areas, isolating each with a monochrome channel in Photoshop. Compelled by the abrupt disconnections between subjects and backgrounds as well as one pure color and another, Welling’s compositions lodge in our minds the way the vivid imagery of a dream does. They puzzle us and compel close looking much as a dream compels memories when we awake.