Curatorial work began on the fifth biennial in the “Made in L.A.” series long before March 2020, and it might be March 2021 before audiences can see it in its entirety. Yet so emphatic is the exhibition’s insistence on the physical embodiment of ideas, the political context of cultural encounters, and the existential imperative for humanistic, history-minded narratives of character and emotion, that it seems the ultimate tailor-made survey for this moment. Ironically, it is also emblematic of the times in that most of it remains inaccessible to the public except for a couple of outdoor and offsite installations, performative works reconfigured for the internet, and a big gorgeous book. Across all these platforms, plans and promises, and within the oeuvre of every artist included, across myriad mediums and styles, the overarching dynamic of a version is, essentially and satisfyingly, storytelling.

The exhibition is installed at both the Hammer and the Huntington, and all 30 artists are included at both locations, so there are two “versions” of the show (get it?). And in fact, the unique architectural settings and experiential contexts of the two venues each lends the works on display their own distinct versions of messaging against divergent backdrops—one a vast sweeping white-box hall hosting ambitious art on a commensurate scale; the other an intimate and classical paradigm of genteel Euro-Western style and art historical paradox.

There is a lot to love at both locations. At the Hammer, you feel the giddiness of big, juicy, edificial sculpture in works like Aria Dean’s mirrored video-art cage and Jacqueline Kiyomi Gork’s carpeted soundbooth on the bridge. Nicola L.’s house-sized purple faux fur multi-user suit sculpture is no longer interactive, which is a shame as it screams to be touched. Patrick Jackson’s “Proposal for a Monument” (2020) combines the scene-stealing landscape incursion of dramatic metal with a sly lack of nomenclature and a hidden private place. It’s installed with a lamppost linking it to MacArthur Park—an offsite location where a suite of billboards by Larry Johnson are currently installed. Original paintings by Jackson are installed at the Hammer in proximity to the sculpture—as are enriched, folk-infused urban genre paintings set in similar locations by Jill Mulleady. It all serves to keep the world outside top of mind, even as the offsite installations keep the museum present in the public imagination.

Patrick Jackson. House of Double, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles.

Patrick Jackson also has one of the most affecting sculptural installations at the Huntington, as his pair of lifelike, life-sized sculptures of a young bearded man lying on the floor in a quiet room, juxtaposed with an 1859 sculpture by Harriet Goodhue Hosmer from their permanent collection. Its stone depiction of a paradigm of white, female, mythological beauty surveys the plight of the prone and mysterious modern figures at her feet with placid disinterest, and yet her neglect, as an emblem of Western culture, is not benign. Actually, this note of instructive dissonance is struck repeatedly in the Huntington version, and that dynamic of counterpoint offers the most outright enjoyable aspect of the biennial.

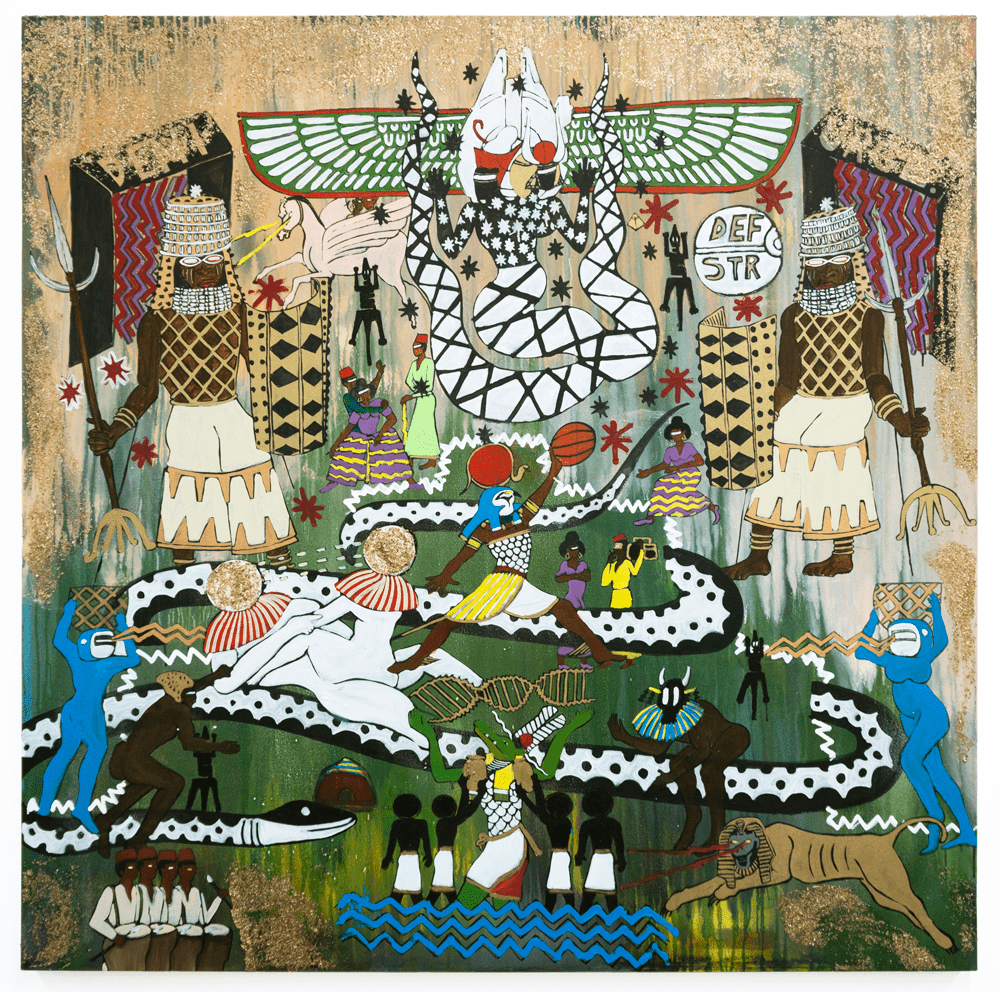

At the Huntington, Umar Rashid aka Frohawk Two Feathers, has a pair of explicitly anti-colonialist tableaux, whose pre-Raphaelite swagger combines social critique with fantasy and humor. Sculptor Ann Greene Kelly shows a confection made of the elements of classical furniture remade into something witty, antagonistic to functionality, and subversive of polite historical antechambers. These works are installed in the entrance, against an ornate stained glass panel and craftsman architectural detail symbolizing the very past the contemporary voices are picking on. When Ser Serpas sets up an array of reclaimed random materials from an ordinary neighborhood and lays them out in a clean, luxurious glass room at the Hammer, it feels like sociology and surrealism; when she does the same embedded in a dusty flowerbed at the Huntington, it feels post-apocalyptic. A piece that’s the same in both places (a period micro-story video by Mathias Poledna) challenges its own temporal gaps as well as mirroring between the venues and offering a perfect starting point for inevitable, encouraging comparisons.

At times quite personal, frequently socio-political, especially on issues of gender, race, identity and commerce, and always with profound empathy, without exception, each work carries the gravitas and courage to dismantle cultural crosscurrents, unearth and reclaim heritages, throw off the yoke of fetishized colonialism, and offer correctives. These artists are so dedicated to their technique and craft that their ideas are not only articulated but embodied in beautiful, majestic, unsettling, tangible objects and salient, resonant character studies and narrative arcs. It’s a snapshot survey, but it tells a singular story—e pluribus unum, out of many, one LA.

Umar Rashid, The Waters of Flint. Source of All Things, 2018. Collection of Marlene Picard.

It was organized by independent curators Myriam Ben Salah and Lauren Mackler, with the Hammer’s Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, assistant curator of performance. And performance is centrally represented across the biennial. Except that, yeah… all of that has been reconfigured for online, well, “versions.” Harmony Holiday is turning a James Baldwin video excavation into a teleplay. Niloufar Emamifar is writing a site-specific theater piece. Ligia Lewis’ “deader than dead”(2020) is a 20-minute, four-person dance, spoken word and music video work using multi-camera editing and set pieces which are installed in the Hammer galleries like artifacts. Kahlil Joseph BLKNWS (2019) video and sculpture works are installed in six (so far) Black-owned businesses around town. The artist Justen LeRoy’s SON (2020) podcast will soon start releasing episodes, combining interviews, insights and musical interludes.

While it’s these dramatic, cross-platform works that get the lion’s share of early attention, there is so much soul in the straightforwardly brilliant, portrait-based paintings by Mario Ayala, Fulton Leroy Washington aka MR. WASH, Monica Majoli, Brandon D. Landers, Alexandra Noel and especially Katja Seib, whose witchy, sketchy, operatic magic realism is just the thing. Eccentric tapestries by Christina Forrer; mural and film-based actions by Hedi El Kholti; diverse photography by Buck Ellison, Reynaldo Rivera and Diane Severin Nguyen; reflective, headline-grabbing collage by Kandis Williams, and heavy-metaphor video by Jeffrey Stuker, all make the case for a proliferation of talented, hard-working, original-minded artists working now, here in Los Angeles.

Sabrina Tarasoff’s labyrinthian “Beyond Baroque” (2020) installation at the Huntington is the Gesamtkunstwerk crescendo of the whole project. It’s based on a legendary, storied group of pioneering west side poets and engineered into a quarter-mile, claustrophobic cabinet of curiosity, charm, deviance, discomfort, dildos, humor and abject horror. Everything you think you know about LA, it seems to suggest, is a psychotic fiction and at the same time, deeply true and lovely.

0 Comments