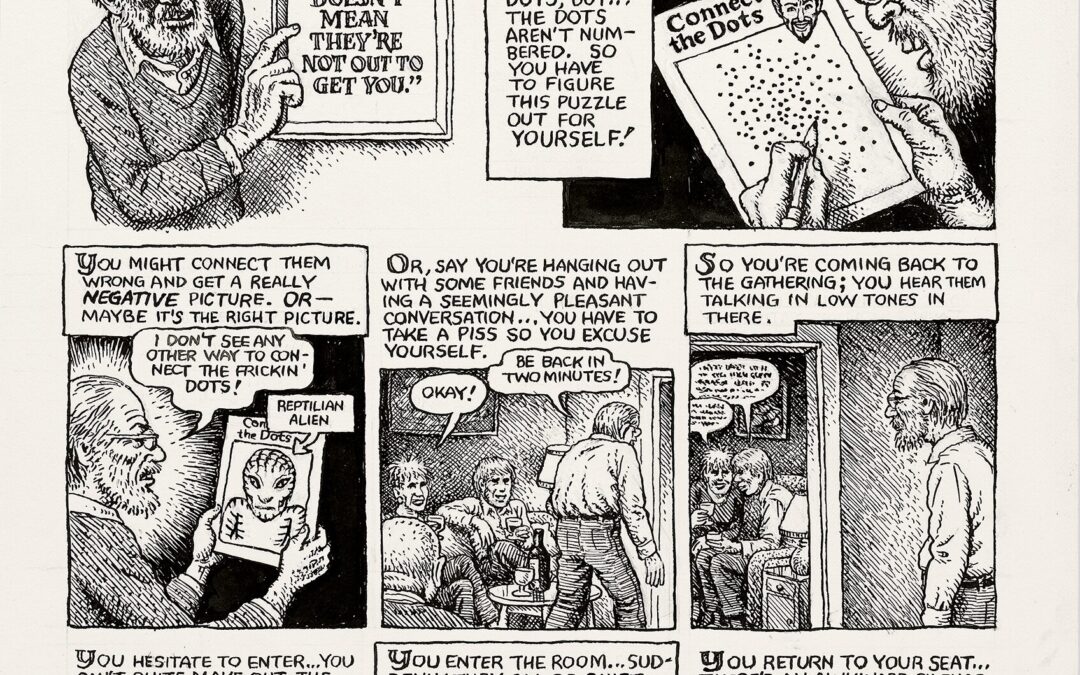

R. Crumb’s “tales” (even filtered through psychedelics and cannabinoids) weren’t always so paranoid—though they were frequently calamitous. The street-hip graphic domain Crumb freely improvised during the 1960s and 1970s across densely cross-hatched black-andwhite...

![The Harrison Studio [Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison] Survival Piece #1: Air, Earth Water, Interface or Annual Hog Pasture Mix (1970-71) at Various Small Fires](https://artillerymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/HAR007_Survival-Piece-2_1971_24x36_Install-View-01.jpg)