Portraiture has been a constant in art-making since the waning Middle Ages, and really since art first appeared (though they wouldn’t have called it that), which may extend back into prehistory. I would further conjecture that such early art itself encompassed a kind of portraiture, whether or not its first subjects were even human. The earliest worlds were also wild places in which predator and prey were probably on slightly more equal footing—each keen to deconstruct (in every sense) the other’s world. Plus ça change.

It’s hard to say whether the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns of 2020 were an impetus for a fresh revival of portrait-making and viewing. But the timing of shows like the Met’s 2021 Alice Neel retrospective, People Come First and the David Zwirner Gallery’s re-mount of the Diane Arbus 1972 MoMA retrospective in 2022 seemed to respond to a moment in which people were re-examining their relations within societies and polities, both with each other and with themselves. ARTILLERY itself made portraiture the subject of its March-April issue this year. Part of that reexamination might well be viewed on a continuum with political and cultural developments of the preceding decade, though on-going brutality and violence inflicted upon communities of color also reminded us that our republic’s own barbaric ‘pre-history’ was never too far away.

Aleksandra Waliszewska, Untitled [Face], 2022–23. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe

The sheer quality of the work exhibited, alongside Gingeras’ curatorial scholarship and shrewd insights into the larger historical and cultural contexts in which artists forged their styles and which shaped their (and our) view of the world, make this a museum class show. But Gingeras has a gift for inter-weaving stylistic, aesthetic, cultural, thematic and narrative threads across historical periods, simultaneously refreshing our view of both historical and contemporary work and bringing them into sharp focus, which puts this exhibition into a class of its own.

Umar Rashid, Autumn in the Schwarzwald (Black Forest)…, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe

The scope of her reframed and recontextualized view of portraitures is apparent from the viewer’s first glimpse. The gallery’s entryway space (“This is what these lives looked like,….”) is hung with a spare selection of 19th and 20th century and contemporary paintings that variously document, reflect, protest, celebrate, fantasize, and mythologize African-Americans’ views of themselves and their worlds. Andrew LaMar Hopkins’ Bridgerton-worthy fantasy Creole Duchess (2023) is flanked by Joshua Johnson’s early 19th century Portrait of a Woman (a white woman, who was likely a patron) and an unknown (‘Louisiana School’) later 19th century Portrait of a Creole Gentlemen. Winfred Rembert’s haunting Pregnant in the Cotton Field (1996) is literally worlds away from the Stettheimer-like charm of Rosalind Letcher’s The Bunny Hop 1965. The incomparable Ernie Barnes gives us a full-on guts-and-glory vignette of a world he knew inside and out in his 1966 Football Players (executed before his retirement from the game!), while the coolest Prussian general in the Black Forest reins in his beautiful white mount en route to a strategy session with his fellow officers in Umar Rashid’s Autumn in the Schwarzwald….

Chidinma Nnoli, They are you, You are them, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe

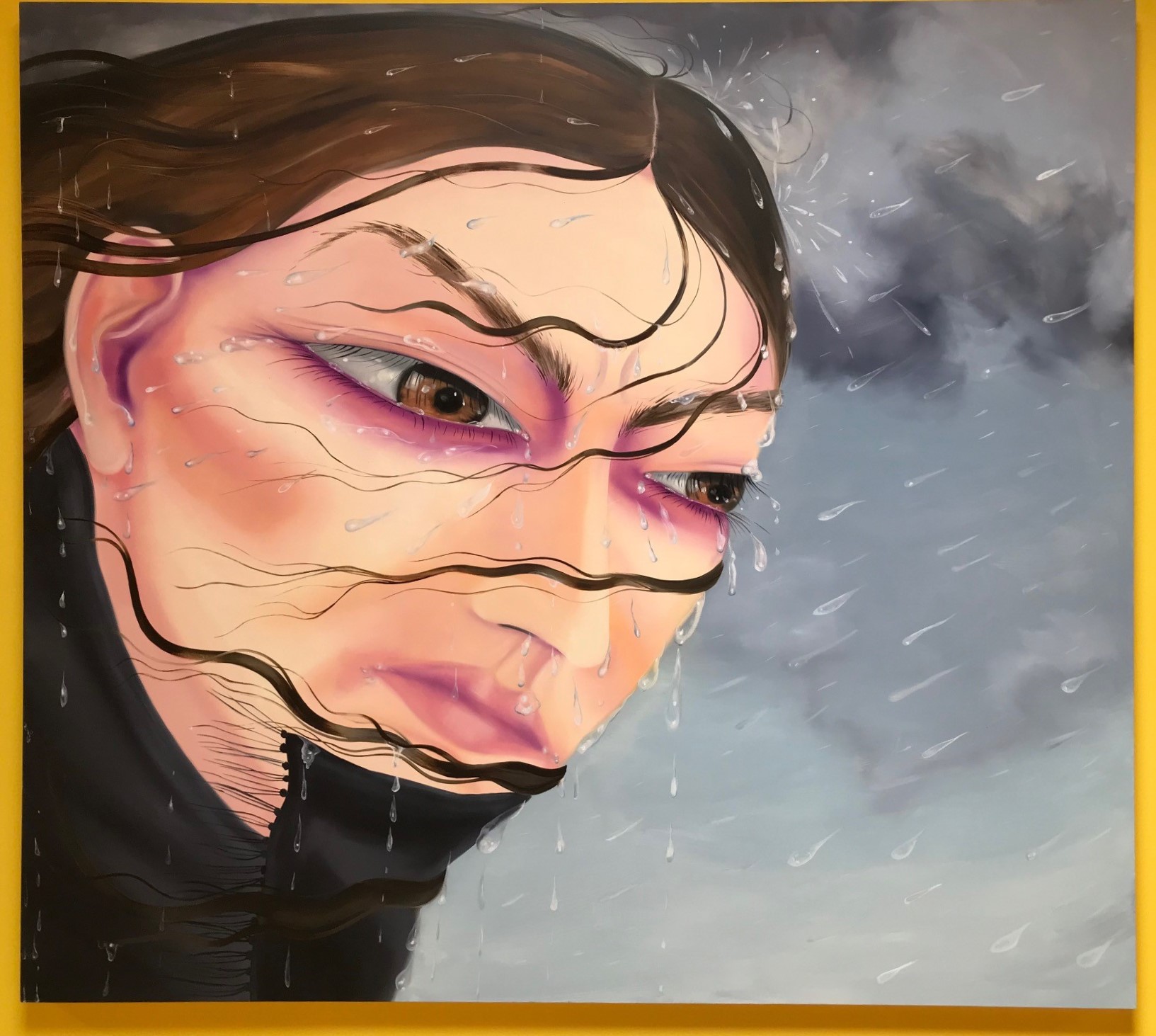

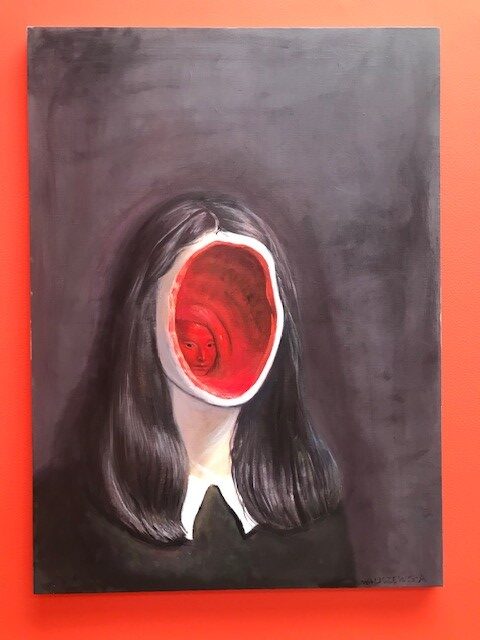

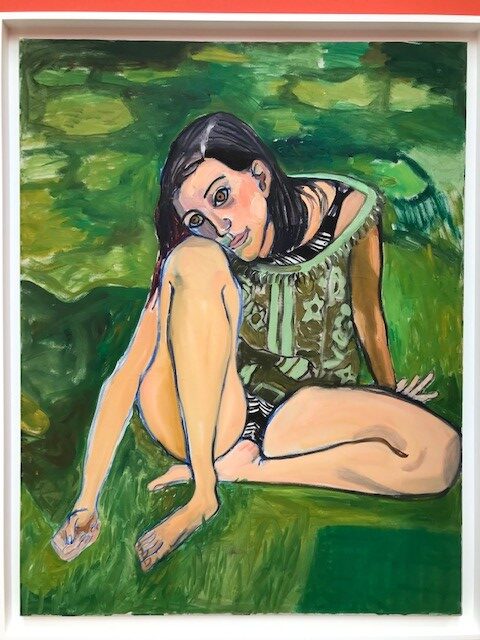

From this alternately sobering, reflective, and soaring entrée, Gingeras gives us a selection of portraits and self-portraits alternately meditative, deconstructed, tentative, self-reflexive, matter-of-fact, and fanciful—or all of these simultaneously (in keeping with her keynote quote (from Joan Brown), for this section of the show, “I am not any one thing….”). Besides Brown, the artists include March Avery, Chris Oh (paying tribute to the 16th century painter Sofonisba Anguisola—only recently receiving long overdue recognition for the power of her portraiture); Katja Seib, Devin Troy Strother (rendering his auto-portrait by way of brilliantly displaced deconstruction), Nigerian artist Chidinma Nnoli, evoking the divided self in a manner and palette rarely seen since Serusier and Denis; the young Polish artist, Agata Słowak’s self-dissection, recalling the most scabrous of post-Expressionism Weimar painting (and for many of us, Stephanie Barron’s brilliant New Objectivity exhibition for LACMA), Mela Muter’s quietly assertive ‘palette-portrait’; June Leaf, and more.

Alice Neel, Nancy Greene, c. 1965. Courtesy of Blum & Poe.

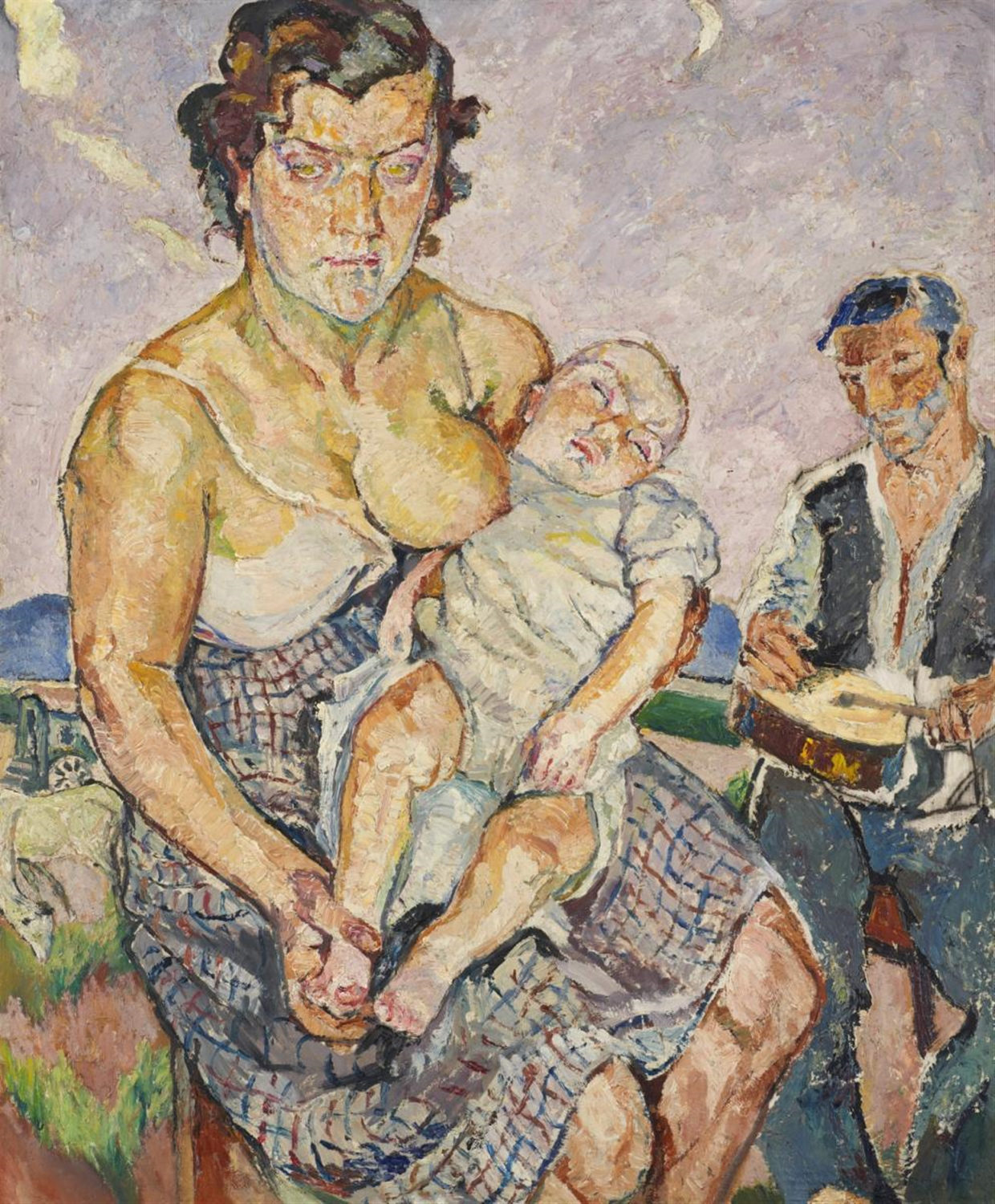

The spirit of Alice Neel anchors the next gallery. People may not “come first” exactly; but certainly she was dead-on in noting that “People’s images reflect the era in a way that nothing else could….” We see this directly in the way people move. Gesture (and style and fashion) are also a huge part of this. But the times (cultural, political, economic) also leave their distinct imprint on the face separate and apart from the toll imposed by gravity, heredity and the elements. Even so, the range of this very concise selection is astonishingly broad—variously coy, casual and forthright, even defiant; illuminated, haunted and almost hermetically surreal. There’s a kind of electricity that radiates off these portraits whether it’s the billowy shadow aura that echoes the contours of Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita’s bobbed-hair beauty or the northern light glow that seems of a piece with the charged gaze of Chicago Surrealist Gertrude Abercrombie’s 1936 self-portrait. The paintings are all extraordinary on their own terms, but the second Muter canvas here, Zigeunerfamille (Gypsy Family) (1930)—a breastfeeding mother all but projecting herself (and her infant) into the foreground, her seemingly reticent musician husband some paces behind her—has a visceral power that almost propels it out of its place in time. But no one escapes history—or mortality.

Mela Muter, Zigeunerfamille (Gypsy Family), 1930. Courtesy of Blum & Poe.

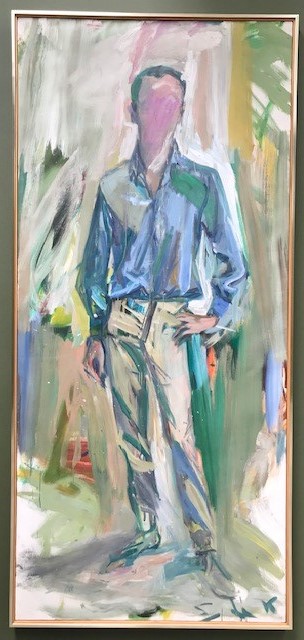

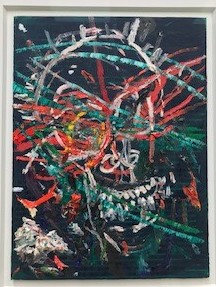

Here Gingeras pivots to poetry—a digression, not a distraction. The portrait is simultaneously mask and unmasking. Larry Rivers famous O’Hara Nude with Boots (1954) is here, alongside Elaine de Kooning’s own 1962 portrait—with O’Hara’s distinct features blurred beneath a pale pink cloud from her brush. (Why does unmasking always seems to portend some kind of legal challenge?) Mark Grotjahn’s Untitled (Skull) nods both to ultimate unmasking and the ultimate mask—no longer to be betrayed by that ‘tongue that could sing once’ or ‘politicians’ that might ‘circumvent god’ (quoting from Shakespeare’s Hamlet).

Elaine de Kooning, Frank O’Hara, 1962. Courtes of Blum & Poe.

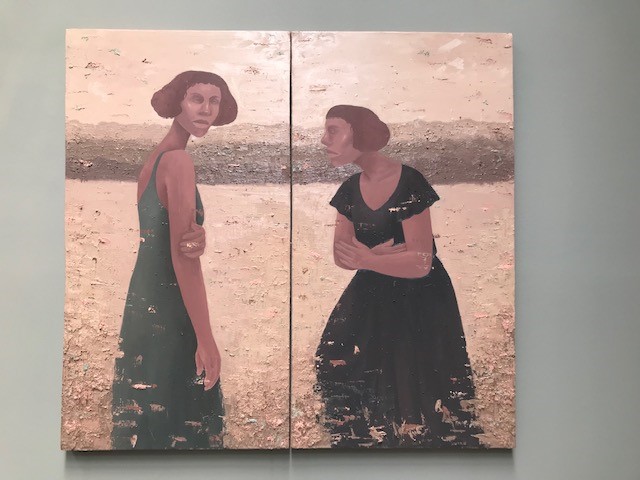

The last two galleries confirm and consolidate the main points of Gingeras’ recontextualization of portraiture and more expansive redefinition of its domain. Setting the Neel affirmation that “People come first” to one side, Gingeras emphasizes both inclusivity and the life stories represented. “Portraits are pictures people make,” she declares, embracing not simply the flux of personal, sexual, racial, ethnic or cultural identity, but an expanded notion of how this can be represented and what it might look like. Her inclusion of works by relatively unknown artists (e.g., Jerome Caja, whose work has a fetishized, almost devotional charge, or Elisabetta Zangrandi, who appropriates Velasquez’s Las Meninas to her own ends), as well as the auto-fictional domain of Karolina Jabłońska and Robin F. Williams’ dissolving film still, confirms this sense of redefinition. We are some distance from Arbus here—not merely entering into other worlds, but the shadows and shadow selves and lives within those worlds.

Gingeras makes clear the extent to which contemporary art has expanded our sense of what portraiture means and what it conveys. But what further sets the show apart from museum shows of similar scope and quality is a connective harmonic resonating from gallery to gallery, even painting to painting. There’s a poetic and musical cadence to the exhibition independent of its affinities with Ashbery, O’Hara, Shakespeare, et al. There’s no ‘discorrupting’ (Shakespeare to Whitman to Grotjahn) the bodies or whatever fascinating traces they’ve left for the rest of us to contemplate. What “Pictures Girls Make” ‘sings’ is an air as free-floating as consciousness itself, and it’s exhilarating.

Mark Grotjahn, Untitled (Skull), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

Blum & Poe

2727 S. La Cienega Boulevard

Los Angeles, 90034

On view through October 21, 2023