“January in the last extant stable society.”

Joan Didion, “In Hollywood” (1973)

— included in The White Album (1979)

“You can get there from here,” was something like the thought rippling just beneath my immediate observations, coming upon several Jessie Homer French paintings just being unwrapped and propped against a gallery wall sometime between 2016 and 2017. (Nothing to do with Shirley MacLaine—though why not?) I can’t remember exactly when, though I do recall a group show in progress. I’m not sure if a show was anticipated at the time, but I hoped there would be. A naïve, ‘outsider’ quality was immediately apparent, though a certain focus and attention to detail conveyed an attitude and ideas adding further dimension. I recall a kind of small-town centripetal aspect: schoolhouse, truckstop, post office, church, cemetery (a landscape that might be located anywhere between New England and the Midwest). Only later did I learn that the ‘regions’ her work described were far more specific—and far closer to home (or at least California).

Homer French has described herself as a “regional narrative” painter; and, depending upon scale and verticality, her pictorial composition is organized along corresponding lines—foreground (or occasionally underground or subterranean), middle ground, and horizon; with a nod to perspectival depth but also an insistent frontality. Recognizable figures and incident populate these ‘regional’ landscapes, but—unlike the sort of ‘primitive’ to which her work might draw naïve comparison—without sacrificing coherence or clarity. They could almost be maps—like a map with illustrated landmarks or regional survey with diagrammed geographic or geologic features. The Dying Sea (2021) is just that—rendered in fabric, with some embroidery and cut-out elements, and others detailed in fabric inks. The subject here is the endangered Salton Sea—literally dying, its suffocating tilapia rendered as white cut-outs with x’ed out eyes washing over the shoreline, pressing against a jagged red San Andreas Fault line with “Joshua Tree(s)” inked in on ‘tacked-on’ pink fabric above a thin white “10 freeway.” (Homer French has done others, more frequently rendered simply as drawings or paintings.)

Jessie Homer French, Rewilding In Chernobyl, 2021.

It would be absurd to try to pin down Homer French’s specific ‘narrative(s)’ in these paintings—almost counter to their spirit. But if there’s a common thread, it’s something like the continuity of communities and their life cycles common to both human and non-human species—even in death. Cemeteries abound in Homer French’s paintings, but their inhabitants persist, still perfectly attired in their burial costumes and neatly arrayed horizontally in the rectangular frames that stand in for their coffins or burial plots—their symbolically remembered state. (One of the paintings here is actually titled Remembrance Day (2021), which, although its soldiers’ crosses topped with memorial lights (and a bagpiper) clearly indicate a military burial ground, also includes a child or two in its subterranean foreground.) Although Ojai Valley, with seemingly endless hectares of variously lush and verdant and dry scrubby terrain would seem to offer her an abundance of landscape possibilities, Homer French singles out two cemetery sections, each with enclosed ‘family’ plots—one without the arrayed bodies.

Jessie Homer French, Ojai, California, 2022.

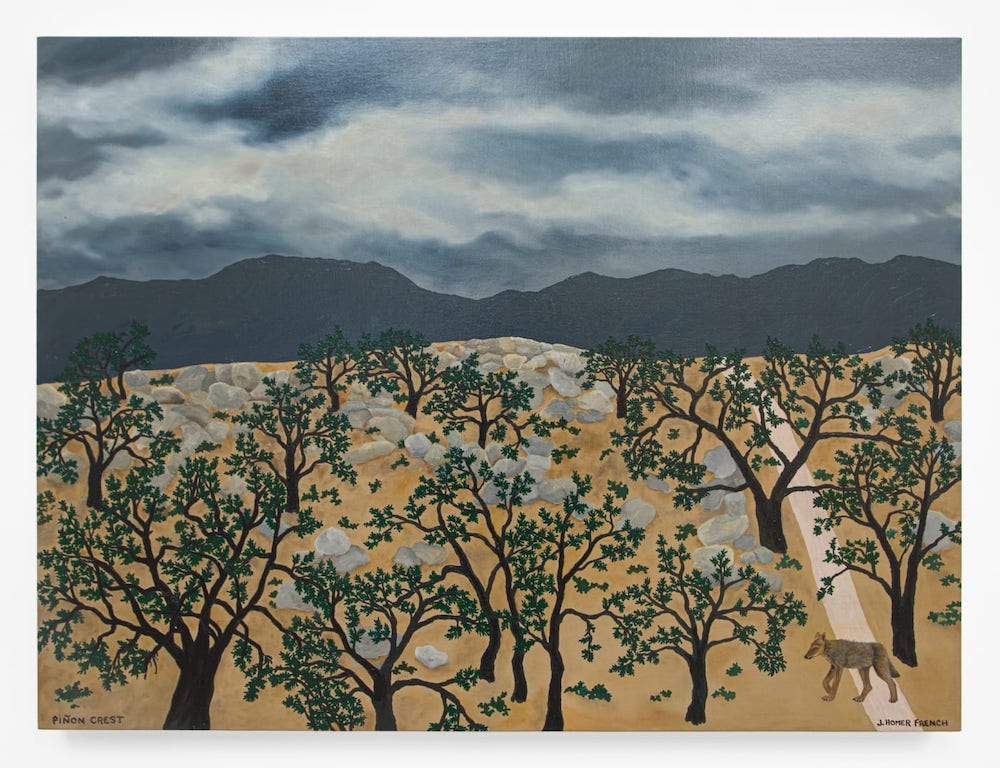

Yet something of the strain to that ‘common thread’ is also visible in the last couple of decades (a period that largely coincides with Homer French’s increasing isolation from Los Angeles and metropolitan cities—she has lived in Pinyon Crest, between the Coachella Valley and the Santa Rosa Mountains since the early 2000’s—as if those human ‘spirits’ were not quite so persistent—or simply no longer relevant. Moving through isolated desert expanses (and presumably above bodies of water), Homer French locates an ecosystem of ‘ghosts’ and machines. In Ghosts (2012), five wind turbines turn (or rest) against a wash of placid morning light in an empty sky, while somewhere in the distance the distinctive silhouette of a stealth bomber plays a kind of ghost moth to what might once have been plant (or other) life covering its ground. Animals and other life persist, however—and seem to comment in humanity’s absence or simply its ineptitude. In North Sea Wind Farm (2023), wind turbines turn against a stormy gray sky, while a shark’s ever-so-slightly curled lower jaw expresses an anthropomorphic dismay at their intrusion in its waters.

We like to think nature is resilient, but successive waves of human devastation leave their mark and take their toll. In Rewilding In Chernobyl (2021), lush growth appears to be overtaking what were once offices or apartment blocks (and the bright radiation warning signs that dot the landscape), but a moose looming out from the green canopy and a catfish in a nearby stream appear freakishly large. The nature that does persist, as Homer French continues to depict it with care and clarity, is stunningly indifferent to human presence. In After Burn and Jimson Weed (2023), beneath a sapphire sky promising moisture already replenishing the green terrain in the middle of the painting, and amid blackened half-dead trees and the weed blooming magnificently out of ashes that match his or her coat, a solitary olive-eyed coyote stares right past us. As Homer French seems to see clearly, the ‘last extant stable society’ might well be a pack of wolves.