A viewer unfamiliar with Blair Saxon-Hill’s previous work might be inclined toward certain assumptions about the foundations and precedents for her style and approach to her subjects—figurative, abstracted or quasi-symbolic—or even what her subjects might actually be. There’s a certain kind of figurative art we’ve been seeing quite a lot of in recent years that “checks a number of boxes”: the quasi-surreal, faux-naïve, sometimes slightly pictogrammatic, the “outsider”- or New Image–influenced. Some of it’s good, some quite good, and most of it pretty “meh.” At best, the general reaction elicited is something along the lines of: “Great. Why?”

Conceivably, there will be viewers inclined to take a similar view of Saxon-Hill’s new work, which, though not entirely discontinuous from work she has recently shown, seems a significant departure from the boldly gestural, animated and performative assemblage work she exhibited at JOAN in 2017—work that referenced both body and body politic under assault. That gallery felt compelled to underscore that this show represented a “major pivot in her artistic practice,” in that the works were entirely oil paintings on canvas. But there may be more continuity than first meets the eye. In one sense, what might have been collage, whether patterned fabrics or other natural or synthetic elements, has simply been distilled into pigment—a style and technique that goes back to Matisse and the Cubists (and still earlier). But Saxon-Hill’s imperative here is not simply to tease or invert it—no tongue-in-cheek trompe l’oeil or faux bois for her.

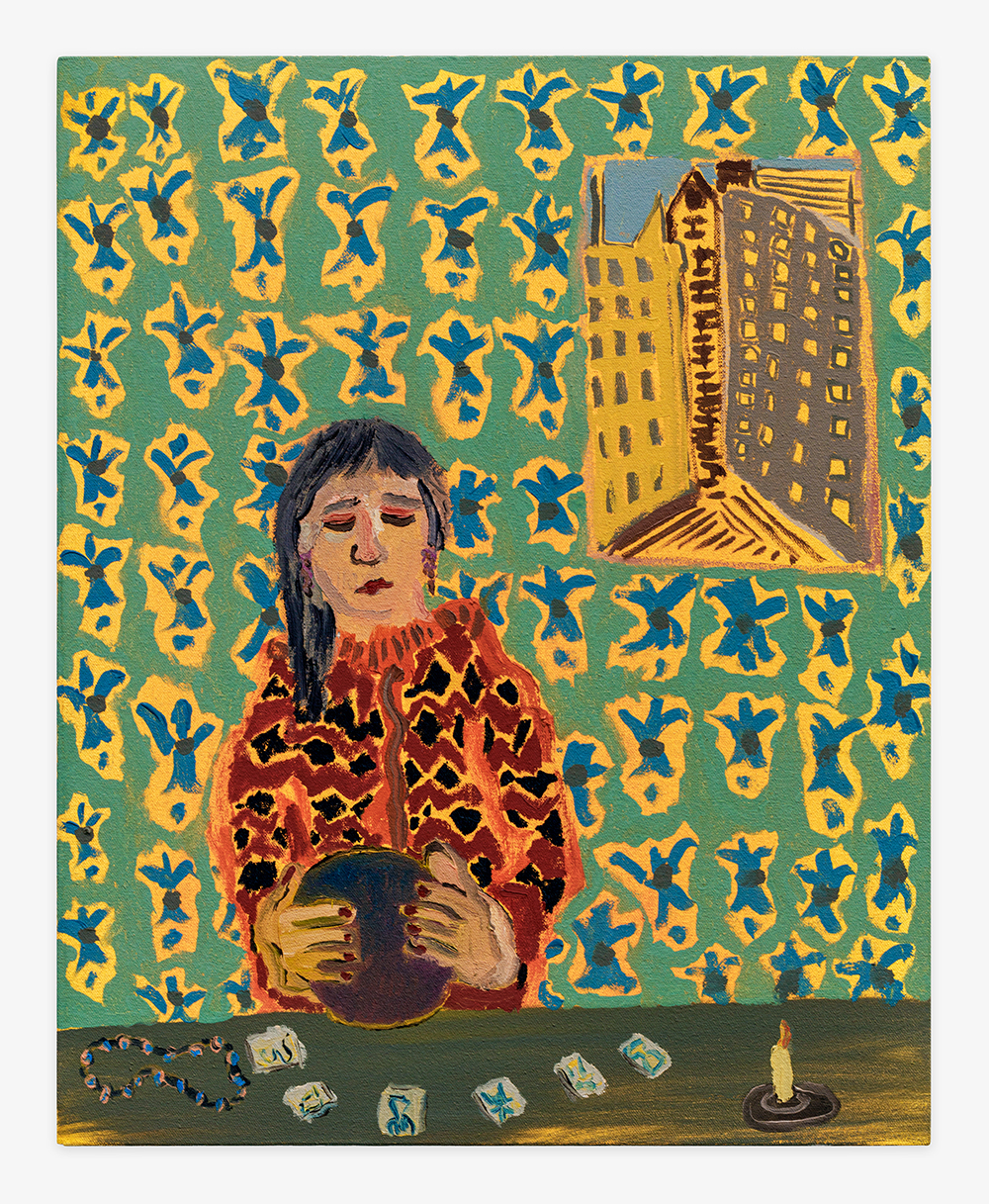

Blair Saxon-Hill, In the Stars, 2023. Courtesy of SHRINE, Los Angeles.

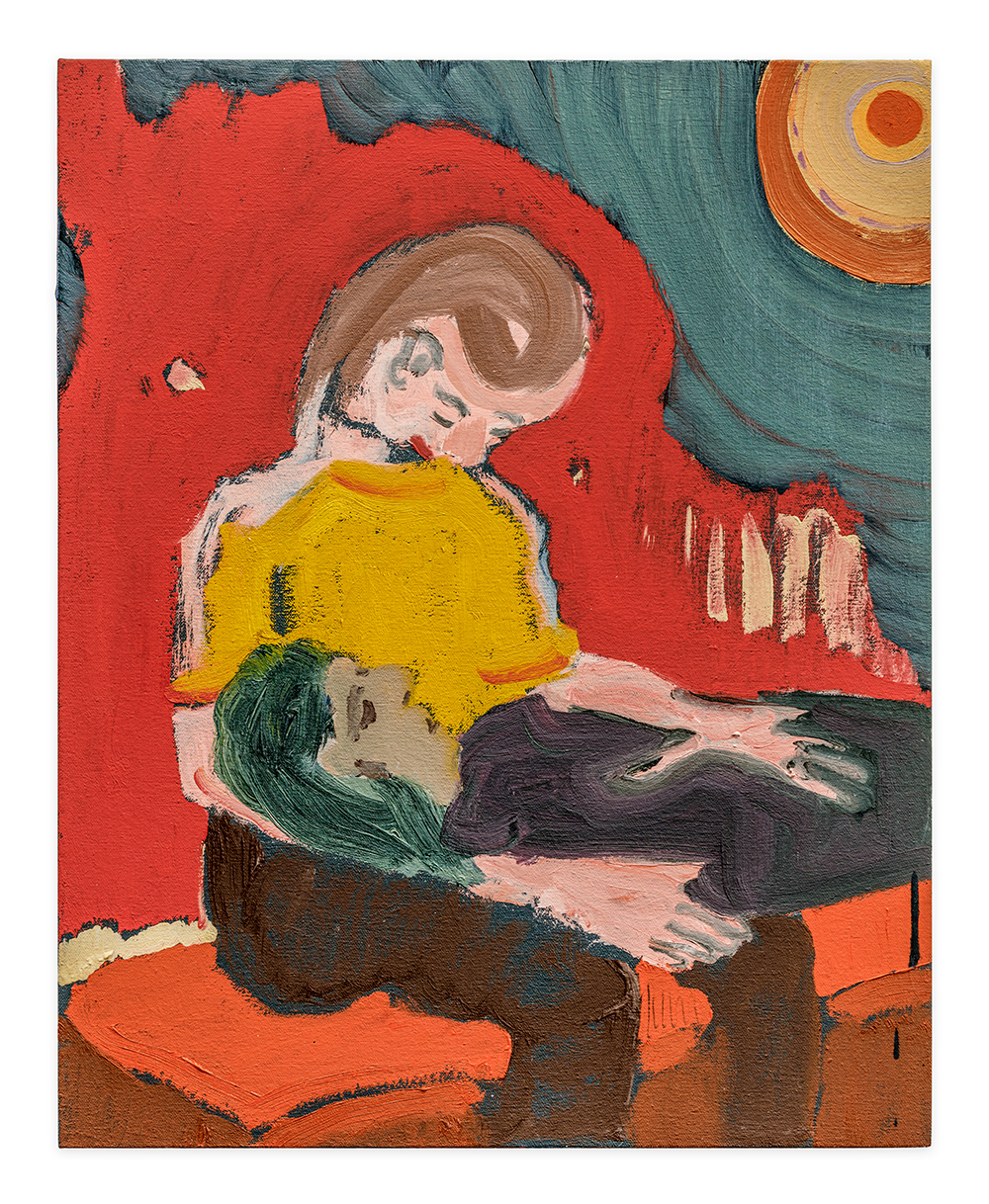

She titles her subjects “Spirits, Queens, Dogs and Flowers,” and she messes with all of them, from The Casual Dog Walker (all works 2023) to the Spring Queen to the Quiet Peacock (each of which could have easily been, in actual flesh, Arbus subjects). She roughs up the elements, but more importantly she emphasizes their irregular, discarded or remaindered eccentricity. The couch melts away beneath the “dog-walker.” The Spring Queen’s

Siberian Husky eyes pop against watermelon wallpaper. Wallpapered peacock tail feathers upstage her Peacock. Everywhere, Saxon-Hill’s impulse is to reduce or strip away. The brushstroke itself becomes form, armature or the figure in its entirety. Consider the brushstroke(s) that make the Peacock’s coiffure, or the oversized gestural white brushstroke that curlicues over the reddened dome of the Spring Queen.

Pattern and textural references notwithstanding, this is not simply paint mimicking collage. Patterns are shuffled and knocked off-kilter—iris petals torn into blue cranes or just splotches; fleurs-de-lys melting into starbursts (In the Stars—with an ambiguously inset picture/window). Broken stripes read (from some distance) as columns of print awaiting their Editor’s scrutiny. The painting is itself a kind of performance and not without urgency. Contradicting its implied romantic premise, The Proposal distills urgency in every aspect—graphically, chromatically and compositionally.

For all their playfulness and chromatic virtuosity, Saxon-Hill’s works embrace the ceremony of her subjects—celebratory, mournful or simply aspirational. (However parodied, the portrait is itself a ceremony of vanity.) The flowers of This Year’s Garden (and the other “flowers” on view here) may be dying; but any promise otherwise is just another three-card monte. In the meantime, we’re encouraged to embrace our spirit animal (or queen)—which Saxon-Hill reminds us is more than likely a dog.