Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Barbara Morris

-

SENSE OF WONDER

Innovation in the Islamic WorldCenturies before Leonardo da Vinci lived and worked in Italy, a Persian astronomer, physician, geographer and writer was conducting research into the nature of the cosmos and man’s place in it. Zakariya al-Qazwini (d. 1283) wrote and illustrated The Wonders of Creation and Rarities of Existence (1280), a remarkable 13th-century document cataloging the earth, the heavens and the many forms of life. This fall, The San Diego Museum of Art will take the beautifully illustrated text as a point of departure for an exhibition of works of art, texts, scientific instruments, magic bowls and commissioned works by contemporary artists Hayv Kahraman and Ala Ebtekar.

Ala Ebtekar is the Berkeley-based child of Iranian immigrants, and Kahraman is an Iraqi refugee now based in Los Angeles. Kahraman has used science and geometry, including work with 3D-scanning and mapping, with the female body—her own—as subject and object in her large-scale figure paintings. Often writhing or contorted, the images explore issues of identity and othering.

Hayv Kahraman, Plucked, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias. The “sense of wonder,” with its emphasis on cosmology, is at the core of Ebtekar’s recent work. Coming from a background in painting, he received his BA from the San Francisco Art Institute and his MFA from Stanford, where he now teaches. The artist has pivoted to more conceptual work and process-oriented techniques, often inspired by the night sky and images brought to Earth via the Hubble Space Telescope. A beautiful immersive tile installation, Luminous Ground (2023–25), created for San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, presents the cyanotype process as a type of alchemy—using light and time to transform organic substances into new forms, their colors shifting from those of earth to sky.

Ala Ebtekar, Safina (exhibition view), 2018. Courtesy of the artist. I recently had the opportunity to speak with Ebtekar. He had just returned from a trip to Dubai, where he had an exhibition—“The Sky of the Seven Valleys”—at The Third Line gallery. It is fitting that Ebtekar, the great-nephew of an esteemed Iranian poet, H. E. Sayeh, framed many of his responses in a poetic fashion. For the PST show, Ebtekar is working on a project that utilizes photogravure and copper etching plates, and imagery of the sun. Underlying the work is an ancient story. The version told by Sufi poet Jalal Rumi describes a contest between two teams of artists—one Chinese, and one Roman—working for the favor of a Persian king. By polishing their own wall to reflect the arduous labors of the beautiful waterfall painted by the other, one clever team clearly finesses the situation. Ebtekar’s wall installation, a grid of rectangular copper plates, will present viewers with their own reflected images as well as a striking composite image of the sun.

Since ancient times, the sun has inspired awe and offered creative power, embodying the very essence of optimism. Ebtekar explains, “I see my work as a journey towards truth, a way to illuminate the path ahead. In these dark times, I search for the morning light that brings hope.” Often, we are driven to produce at a rapid pace, with more and faster, seen as our ultimate goals. As suggested by the meditative objects and thought-

provoking works on display, it can be equally valuable to slow down, step back and allow our consciousness to drift for a while in the shifting currents of perception. -

HYPER-REAL HYBRIDIZATION

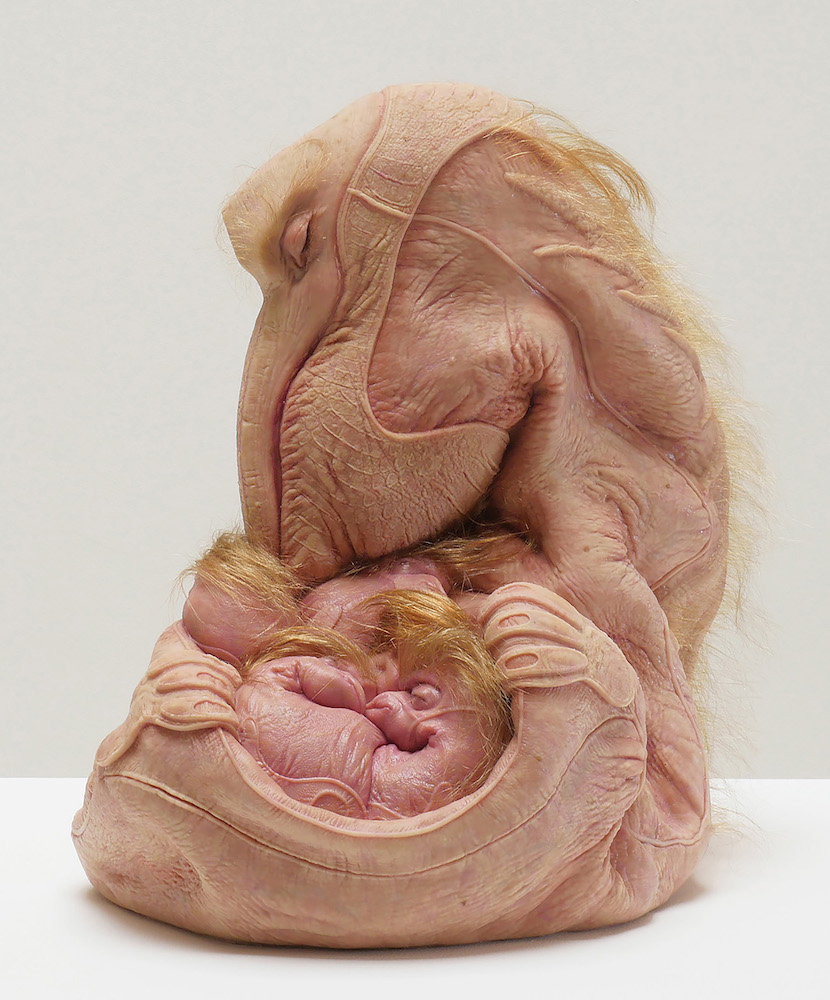

Patricia Piccinini Finds Beauty in OthernessAustralian artist Patricia Piccinini’s world is inhabited by creatures that suggest genetic engineering gone awry or the infusion of sentience in hitherto inanimate objects. Her hyper-realistic sculptures combine elements of human form blended with those of animals, machines and plant life, raising questions about our response to beings who do not meet our expectations of normalcy. These hybrids, created from silicone, human hair, leather, fiberglass and other materials, are unnervingly convincing.

Piccinini represented Australia in the 2003 Venice Biennale and has since been widely shown internationally. Her confrontational, emotionally charged work has clearly struck a nerve, and her 2016 solo museum exhibition in Brazil was the second-best attended show worldwide that year. Her works span still and animated sculpture, installation, photography and film—along with a pair of giant hot air balloons representing lactating whales.

At San Francisco’s Hosfelt Gallery, her 2023 exhibition, “A tangled path sustains us,” placed various hybrid creatures in an immersive, diorama-like woodland setting based on California’s redwood forests. Piccinini is the visionary force behind a small team of creative collaborators that includes her husband, Peter Hennessey. One member is responsible solely for the rooting and placement of body hair—eyebrows, eyelashes and all.

I was recently able to Zoom with the artist, who spoke from her home in Melbourne, to learn a bit more about her background and what motivates her work. Born in Sierra Leone, she returned to her father’s village in Italy, between Milan and Bologna, at the age of three with her family, where she lived a “very secure” and community-oriented life. But when Piccinini was seven, life took another abrupt change with her family’s move to Australia. “When we migrated,” she says, “I experienced a kind of bewildering change of culture.” This early outsider feeling affected her deeply and continues to inform her work.

Clutch, 2022. Her interest in a post-human worldview was sparked by an art class at the University of Sydney taught by Australian feminist Elizabeth Grosz, as well as Donna J. Haraway’s book, A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), which refutes traditionally held dichotomies as ill-conceived and outmoded. Haraway’s book emphasizes that advances in evolution, genetics and technology have blurred the boundaries between animal and human, natural and artificial, and human and machine. A feminist perspective, along with a deep empathy for all creatures in the world, is a key component driving her work. Much of the work considers the idea of care—for a child, a loved one, an animal. She is adamant about the beauty and significance of birth, and feels it is undervalued in our society.

Piccinini refers to her hybrid creatures as “chimeras,” the name coming from the fire-breathing creature in Greek mythology that was part-lion, part-goat and part-serpent. The cautionary tale of Mary Shelley’s Frank- enstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), was “seminal” to her work. “It’s really a story about bad parenting,” Piccinini states, “about a father who is unwilling to care for his son.”

One of her most visually and thematically complex works is the pelican-inspired Clutch (2022), part-bird, part-gestating mammal and part-cowboy boot. Piccinini’s tendency to throw in inanimate features adds an unexpected element that makes the sculptures even more bizarre, often offering a more humorous note. While some may find her creatures creepy, off-putting, or even horrifying, that is not the artist’s intention. She truly loves these misfits, as is reflected in the infinite care with which they are constructed.

Safely Together, 2022. As the cowboy boot evolves into the head of the pelican, the evocative texture of the skin and boot are fused together seamlessly. The tiny, dewy-looking “boot-chicks” are cradled in the womb-like fold of the pouch. Piccinini is not one to shy away from celebrating the marvels of nature, including the deep folds and tender orifices so often off-limits in our culture. She feels that part of her strategy as an artist is to put people off a bit at first. As she admits, “Maybe they’ll find the work grotesque, but then they will get drawn in, and come to like or even love it as interest overcomes their initial resistance.”

Some works, such as Big Mother (2005), Safely Together (2022) and While She Sleeps (2021), are inspired by real-world events—a grieving mother baboon kidnapping a human baby, the relentless poaching of the pangolin, the only mammal with scales—or the hunting to extinction of thylacines, also known as Tasmanian tigers, perhaps unjustly accused of sheep-killing proclivities. These creatures are in so many ways one with us, according to Piccinini. They display strong emotional connections in an envisioned trans-species, post-human world. Rather than threatening, these beings display a haunting vulnerability and longing for acceptance, their freakishness acting as a metaphor for our own frequent experience of being “othered.”

The hybrid beings Piccinini creates, such as in the heartbreaking The Couple (2018), act as our avatars in an only slightly speculative world of “what if?” This work, which depicts a couple embracing in a tent, has been re-envisioned in an upscale apartment setting for the artist’s recent show “HOPE” at Tai Kwun in Hong Kong. Piccinini was excited to share news that it will be traveling to Jakarta later this year.

Reflecting on genetic experiments, and the close kinship of this procedure to the mashed-up body parts of Frankenstein, Piccinini asks, “What is our relationship to these creatures that we create? And how do we feel about them?” Of nature’s own ability to adapt in the face of adversity, she notes, “Out of a lot of negative things come positive things.” Piccinini’s own extraordinary work is one such hopeful note.

-

Our Bodies, Our Business

More Fodder for Michele Pred in a Post-Roe EraOakland-based Swedish-American artist Michele Pred achieved notoriety in the early 2000s for her conceptual sculptural installations of items like Swiss Army knives and manicure scissors confiscated by airport security. Pred’s witty and dramatic work, with a strong Pop-inflected emphasis on bright colors and geometry, clearly hit a nerve.

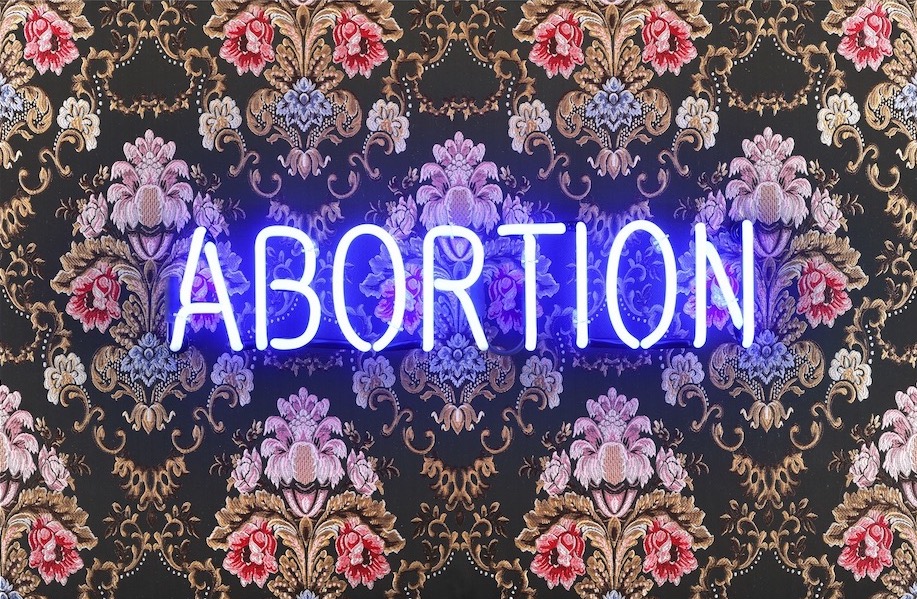

In 2014, she was inspired to shift to vintage purses as a primary medium, fashioning words out of glowing EL wire:“Pro Choice,” “Feminist as Fuck,” and “Pussy Grabs Back”a few of the options. The purse, as both a symbol of oppression of women, and of their economic power, offered a double-sided tool. Pred’s work has suddenly acquired an even deeper significance, with the overturn of Roe v. Wade. A dark time, certainly. I caught up with Pred hoping she might shed some light on the subject.

Artillery: You grew up in Berkeley, where your father was a professor at UC and a political activist, and your mother was from Sweden, with a feminist perspective. Can you tell us a bit about your upbringing and how it informs your art practice?

Michele Pred: My father was in the department of cultural geography and very much an activist; coming from Sweden, my mom was a socialist and a feminist. We spent summers there, so I grew up seeing different possibilities, like socialized medicine, and free education.

What steered you in the direction of fine art?

It was always in my blood. I respond to and comment on the world around me by making things. I started out in photography. Then at California College of the Arts I was already doing political work around women’s body issues, and reproductive rights. And that was in 1990!Tell us a bit about how you began combining vintage purses with electroluminescent wire bearing feminist slogans.

I have always been very interested in using my body as a canvas, and have been intrigued by purses, by what we carry in them. I had been doing a lot of neon pieces on cases, that you couldn’t carry around, with feminist slogans. And I started thinking it would be really fun to carry them. So I made the first purse and took it to the opening night of The Armory Show in 2014, it said “Choice” on it… and people really responded strongly to the purse! Art galleries are such privileged spaces—taking the work out into the streets and engaging with people is interesting to me.

Michele Pred, Abortion is Healthcare, 2022. Neon, resin abortion pills and tapestry. Image courtesy of the artist. Your purses have been carried by some amazing women. What are some of your favorite ways they’ve been taken into action?

Hillary Clinton and Amy Schumer have been photographed with them; Amy showed hers on Instagram. One side says “Pro Choice” and the other side “Nasty Woman.” They’ve been on the red carpet at the Oscars. Ariana DeBose owns one, and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot recently took hers on stage. She says she’s obsessed with it.Your show this fall, “Equality of Rights” at Nancy Hoffman Gallery, includes replica abortion pills. Can you tell us a little about this new work?

Yes, the abortion pills, I had a thousand of them fabricated in resin, enlarged so no one would mistake them for actual pills, and I’m making a flag. I have also just made these sterling-silver abortion-pill necklaces; I’m really excited about them! Then there are works using the scales where I’m using dollar bills I’ve painted pink, which relate to my “Art of Equal Pay” Project.Where you are asking women artists to commit to raising their prices by 15% to address the fact that women artists earn on average 15% less than men?

Yes, and I’m also asking curators, gallery owners and collectors to pledge to support the artists by showing and collecting their work at the higher prices. You can sign up online at theartofequalpay.com, and there’s a survey. It’s a longterm project.You are also curating a Pro-Choice billboard exhibition, “Vote for Abortion Rights,” to be installed across the country. How many billboards will be included?

We’re hoping for 10. They won’t necessarily be in California—we don’t need them here.Your work is important and timely. Are there other projects you’d like to mention?

“The Talking Tree A Space for Civic Discourse.” I want to bring together people from different viewpoints and have conversations—to try to find a middle ground. I think we have to. We have to do that. -

Book Review: Ballerina Looks Back in Style

Serenade: A Balanchine Story by Toni BentleySerenade: A Balanchine Story

By Toni Bentley

320 Pages

PantheonAs a thin, athletic girl with a springy jump and “not-so-great feet,” Toni Bentley was 11 when she entered the School of American Ballet; she was invited into the New York City Ballet company by George Balanchine at 17, and she performed with them for 10 years, until a hip injury cut her career short. With her prolonged devotion to Balanchine as the backdrop, it is their shared passion for the art form that drives the plot of her new book, Serenade.

Balanchine arrived in America at the behest of eventual NYCB co-founder Lincoln Kirstein, then a visionary and well-connected young Harvard grad. Once arrived, the prolific Balanchine quickly set to work, and the challenging Serenade was the first full-length ballet he composed in his new homeland. The initial performance, in bathing suits and thrown-together costumes, was held in the rain on a makeshift stage in 1934 at a benefactor’s party. Forty years later, author Bentley would first dance the role of one of the four “Russian Girls.” She would go on to perform Serenade 50 times.

Woven throughout the biographical, autobiographical and historical material is a re-creation of the 32-minute, 49-second ballet broken down minute by minute, step by step, from before the curtain rises. We are taken backstage, vicariously rubbing our pointe shoes in rosin and taking places on the stage with Bentley, in a position most uncharacteristic for ballet dancers, parallel. A ballet dancer’s turnout, Bentley postulates, elongates the line, and simultaneously emphasizes and symbolizes the physical and emotional openness—a wrenching apart of body and soul—necessary to adapt to life as a dancer. When—at three minutes, 49 seconds—the entire corps de ballet dramatically pivots from parallel to first, feet at 180º, it evokes a dramatic response: the essence of classical ballet distilled to its most basic premise.

A key element in Serenade is the way in which the emphasis shifts from the traditional model of corps de ballet as mere backdrop against which soloists perform, to one in which each dancer may at any moment strike out into movement which is integral to the structure of the whole. Balanchine’s choreography here clearly displays a revolutionary new spirit of democracy.

If Balanchine’s personal life and human imperfections are a bit glossed over, we may learn more than we ever dreamt of, or perhaps wanted to know, about composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and choreographer Marius Petipa, whose emotional struggles and personal demons are outlined in vivid detail. Bentley’s focus, however, is on Balanchine’s genius, his impact on her own life, and the legacy of the phenomenal ballets that he left behind—Serenade, she asserts, is the finest of them all. Like most of his works, it is both plotless and dense, with suggested narrative and emotional content. He wished to share a story of a man and a woman… or two women, or perhaps three women. Women were his muse and his inspiration, as well as the medium through which he expressed himself. While treading gently on the imprint of Balanchine the man, Bentley makes a striking case for the enduring and profound impact of his brilliant choreography

-

Leila Weefur’s Hymns for Other Voices

Uncomfortable QuestionsExplorations of gender identity are central to the work of Oakland-based artist and curator Leila Weefur, how they felt that their identity was suppressed by belonging to the Christian Church is at the crux of their latest project, “Prey†Play.” Presented in two separate and complementary incarnations, both in San Francisco, one is at Minnesota Street Project, as part of their California Black Voices Project, the other at Telematic Media Arts. Many such twinnings and juxtapositions are found in Weefur’s work, who laughs and acknowledges, “Yes, I’m pretty interested in duality.”

We meet at Minnesota Street Project on one of the artist’s rare days away from their teaching responsibilities—this fall Weefur is a lecturer at both Stanford and UC Berkeley. Their own academic background includes an undergraduate degree in journalism from Howard University, followed by a degree in film from Cal State LA. Weefur then spent several years in the film industry in LA, working on music videos, independent films and reality shows.

It was during this time working in the film industry that Weefur decided to shift to fine art. In the 2010s, it was before the advent of the “movement around contemporary Black cinema” and their interests in any event lay outside the “formulaic structure” often found in Hollywood. Seeking out a liberal arts college, Weefur returned to the Bay Area, to Mills College, where their interests in cross-disciplinary exploration were satisfied by studies in the book arts, creative writing and music departments. The latter is where they met composers Josh Casey and Yari Bundy, who form the duo KYN, with whom Weefur has continued to collaborate on the immersive soundtracks for numerous projects, up to and including “Prey†Play.”

Between Beauty and Horror, 2019, video still, courtesy of the artist. Weefur’s current work builds on earlier film installations such as Blackberry Pastorale Symphony #1 (2017), Noise and Thirst (2018), and Between Beauty and Horror (2019). The first references the phrase, “The blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice,” a reference to the idea that darker-skinned Black women were somehow perceived as more voluptuous, sexier, in the context of “colorism”—racism against darker-skinned Blacks. Weefur, who never connected with the idea of the femme Black body, creates potent images of men and women interacting with, crushing and consuming, blackberries. Noise and Thirst evolved in response to the artist being accused of stealing from a market in San Francisco by a woman who described Weefur to the police as a “Black man.” It functions as “an experimental sound collage expressing the cadences of Black masculinity.”Between Beauty and Horror “teases out the uncomfortable dynamics and violence that are present in racism” and, as the artist describes it, “performative Blackness.”

Between Beauty and Horror, 2019, video still, courtesy of the artist. Drawing on their personal experience of the constraints and rigidity implicit in Black Christian churches, Weefur paints a picture that is nuanced and bittersweet, with the pageantry and allure of the church, it’s promise of salvation and the love of God, contrasted with the subtle and not-so-subtle ways religion has worked to control those under its sway. At Minnesota Street Project Prey†Play: A Gospel is set in a darkened space defined by three imposing arches. The video is set in Havenscourt Community Church in Oakland, where the artist was baptized, with red-upholstered pews and stained-glass windows. We hear a childlike voice speaking. “Stand up. Bow your head. Bring the palms of your hands together. Close your eyes. Talk to God.” As the narrator speaks, the actors perform symbolic gestures. Weefur intends the nonbinary characters to act as a point of entry for many different people—a spectrum of LGBTQ and BIPOC, as well as many others.

PLAY†PREY: A Performance, 2021, image courtesy of the artist and Minnesota Street Project Foundation, photo: Jenna Garrett. The narrator continues, “Dear God, can you see me?… I come in afraid to show myself.” At a young age, perhaps 10, Weefur first became aware of gender discomfort, “I knew I was never going to give birth to a child,” and their parents eventually relented and allowed them to wear pants—rather than a dress—to church; they left the church after baptism at age 15. The narrator speaks, “Power is only power if everyone wants it, and no one has it. I used the only power I had, the power to remove myself from view.”

The actors hide within the pews, then reveal themselves, playing hide-and-seek, then peek-a-boo. These gentle games act as a metaphor for early experiences. The atmosphere darkens as a stern voice intones lines from the Black writer and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones, his “sermons” on themes common in Black preaching, and an image of his poem “The Judgment Day” appears on the screen. We see images of fire, candles burning, a charred sprig of blackberries. This leads us into the work at Telematic Media Arts, Prey†Play: The Old Testament, where Weefur fills the screen with an image of a burning Bible.

PLAY†PREY: Old Testament, 2021, video still, image courtesy of the artist and Minnesota Street Project Foundation. Telematic, a much more compact space, sandwiches the viewer between the imagery as a burning book sizzles and snaps, gray flakes of ash curling up and blowing off: Turning, one is startled to catch their own reflection immersed in the video—this side actually a reflection. Weefur likes to catch one off guard, “seeing themselves implicated in the work structurally and conceptually.” Wax candles in the form of crosses lie heaped in a corner, the contribution of collaborator Sandy Williams IV. There are 506 of these, equal to the number of times the word “fire” appears in the King James Version of the Bible. A performance event was also held by Weefur in the nearby St. Joseph’s Art Society, with five other queer and trans writers invited to share “prayers” to be performed with ritual within the highly charged environment of this former Catholic church.

Winding down our conversation at Minnesota St. Project, Weefur reflects for a moment, then speaks, “ …it’s like a child wanting to run around on a field of grass, but there are sanctions that tell you you can only run so far. Like Jim Crow laws, it tells you there’s only one place you can go. That certain places aren’t for you.” Addressing issues very much of this moment, Weefur’s fascinating work raises uncomfortable questions of how we see ourselves, and each other, on a very fundamental and intimate level.

-

Jim Melchert

Gallery 16 / San FranciscoThe centuries-old practice of Kintsugi, a Japanese technique of mending broken pottery with gold, honors the flaws in the ceramic piece. The artist Jim Melchert, who taught English in Japan for four years, has long appreciated and employed that aesthetic. For more than 30 years he has worked with prefabricated ceramic floor tiles, which he breaks, reassembles, then marks with glaze. His meditative attention to the cracks elicits a careful and deft response, hinging on an element of randomness and chance, reflecting in his work the important influence of John Cage.

The recent survey of his conceptually driven work, “Rethink, Revisit, Reassess, Reenter,” includes pieces dating from the 1970s onward.

An iconic figure on the Bay Area scene since the 1960s, the artist studied at UC Berkeley with ceramic firebrand Peter Voulkos, earning a second MFA in ceramics in 1961—he already held an MFA in painting from the University of Chicago, and a BA in Art History from Princeton. Energized by meeting Bay Area artists William Wiley and Bruce Nauman, Melchert soon expanded his practice.

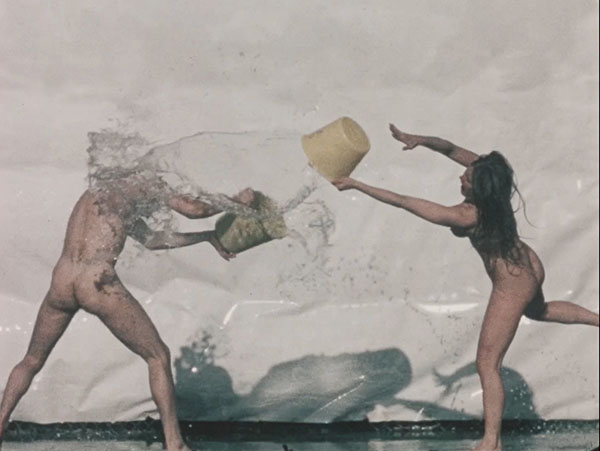

Jim Melchert, Shards Speaking For The Group 13, 2021. Courtesy of Gallery 16. The exhibition primarily features wall-mounted ceramic tile works, but also drawings, sculptures and films. Two of the films included in the exhibition are of particular interest. In Changes, Amsterdam (1972), Melchert and a group of plucky participants dunk their heads in a washtub of clay slip, then sit quietly on a bench as the muck drips and congeals on their faces. The large-scale projection of Untitled (The Water Film) (1973), directed by Melchert and filmed by Peter Ogilvie, features nude performers frolicking before a white drop cloth, flinging buckets of water at each other in a playful homage to Muybridge’s motion studies.

The right side of the large gallery is filled with a grouping of materially and thematically related tile works. North Atlantic (2005) is an immersive work at 90”x72”, a five by four grid of 18” tiles that employs wavering bands of deep blue glaze suggestive of the sea and conjures hypnotic rhythms on the gray tiles. The feeling is meditative, conveying a serene effect. Melchert’s most recent works are smaller in scale, brilliantly hued, and joyous, such as Shards Speaking for the Group (2021).

In 1977, Melchert was invited to direct the Visual Arts Program at the NEA in Washington, DC, where he remained for four years. After a few years back in the Bay Area, he headed to Italy where he directed the American Academy in Rome from 1984 to 1988. These posts clearly speak to Melchert’s prodigious gifts as a teacher, mentor and facilitator. At 91, Jim Melchert remains passionate about art—his own, and that of others. His continuing ability to shape and mold the contours of our art world remains fully as much an expression of his creativity as his diverse and remarkable art practice.

-

OUTSIDE LA: Nam June Paik

SF MOMANam June Paik, the “father of video art” and the man who coined the phrase “the electronic superhighway,” weaves humor, Buddhism, technology, music and sex. Paik was born in 1932 in Japanese-occupied Korea. Tutored in piano and composition, he attended college at the University of Tokyo. He moved to Munich, Germany, in 1956 to study musicology and connect with the experimental music scene, attending lectures at the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music given by John Cage, whose conceptual and revolutionary way of looking at composing and performing would alter the course of his life.

Cage, renowned for his avant-garde compositions like 4’33”, scored silence, became a role model for Paik, who along with Alison Knowles, La Monte Young, George Maciunas and others formed Fluxus, an international collective of musicians, artists, poets and performers with a Dada-inflected sense of anarchy. When Paik assaulted him, cutting off his necktie, in the audience at Etude for Pianoforte (1961) in Cologne, Germany, Cage took it in stride. He did however, allow as how “he’d think twice before attending another performance by Nam June Paik.”

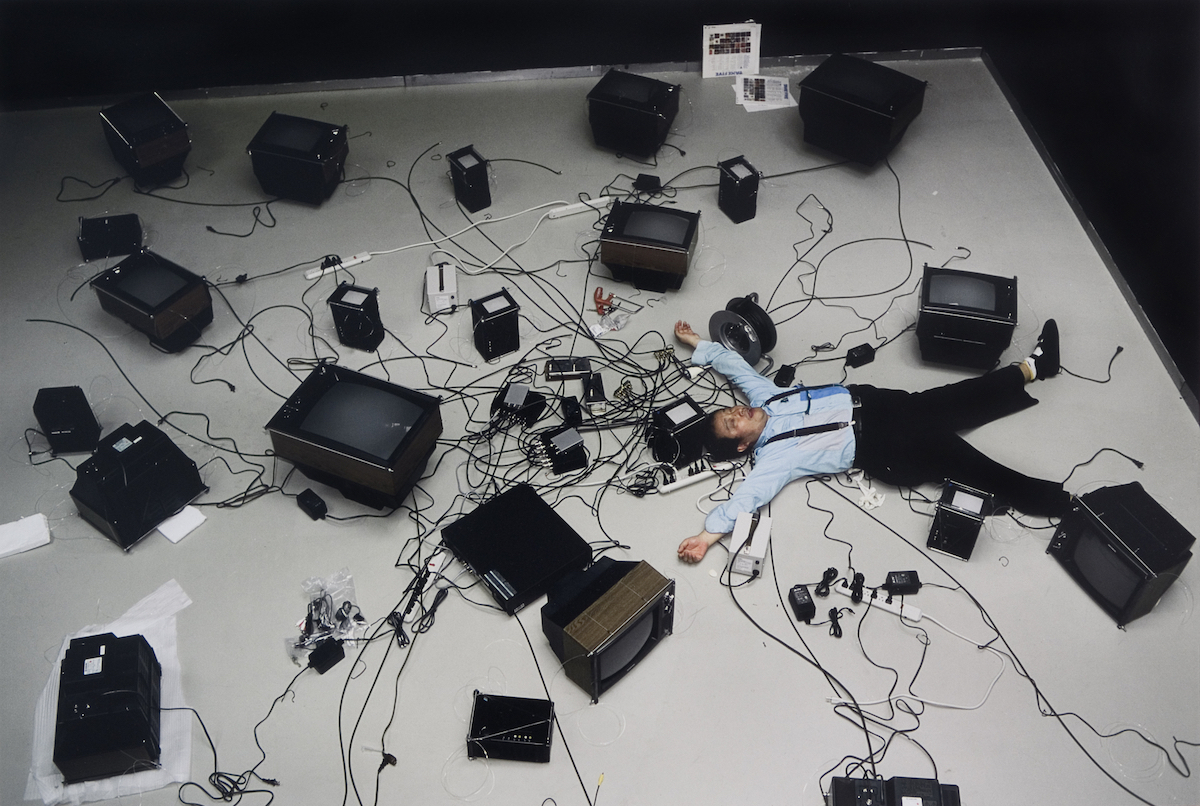

Timm Rautert, Nam June Paik lying among televisions, Zürich, 1991; © Timm Rautert The sprawling “Nam June Paik: A Retrospective,” a joint project of Tate Modern and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, will be presented at five venues. Paik, who studied Japanese, German, English and French in addition to his native Korean, epitomizes the multi-cultural artist, embracing a transnational identity that also left him always as a bit of an outsider.

Originale, an avant-garde event first organized by composer Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne, Germany, in 1961, featured Paik pouring flour and water over his head, throwing beans at audience, and executing some slow-motion gestures. Entering the exhibition, we pass a larger-than-life video of Paik’s Hand and Face (1961) concealing his face with both hands, then separating them as he strokes forehead and chin. Eyes half-closed, he seems in an otherworldly or meditative state. A TV displays The Button Happening (1965), recreating a sequence of jacket buttoning/unbuttoning, flickering in and out of a field of static, that conveys a barely sublimated sexual tension.

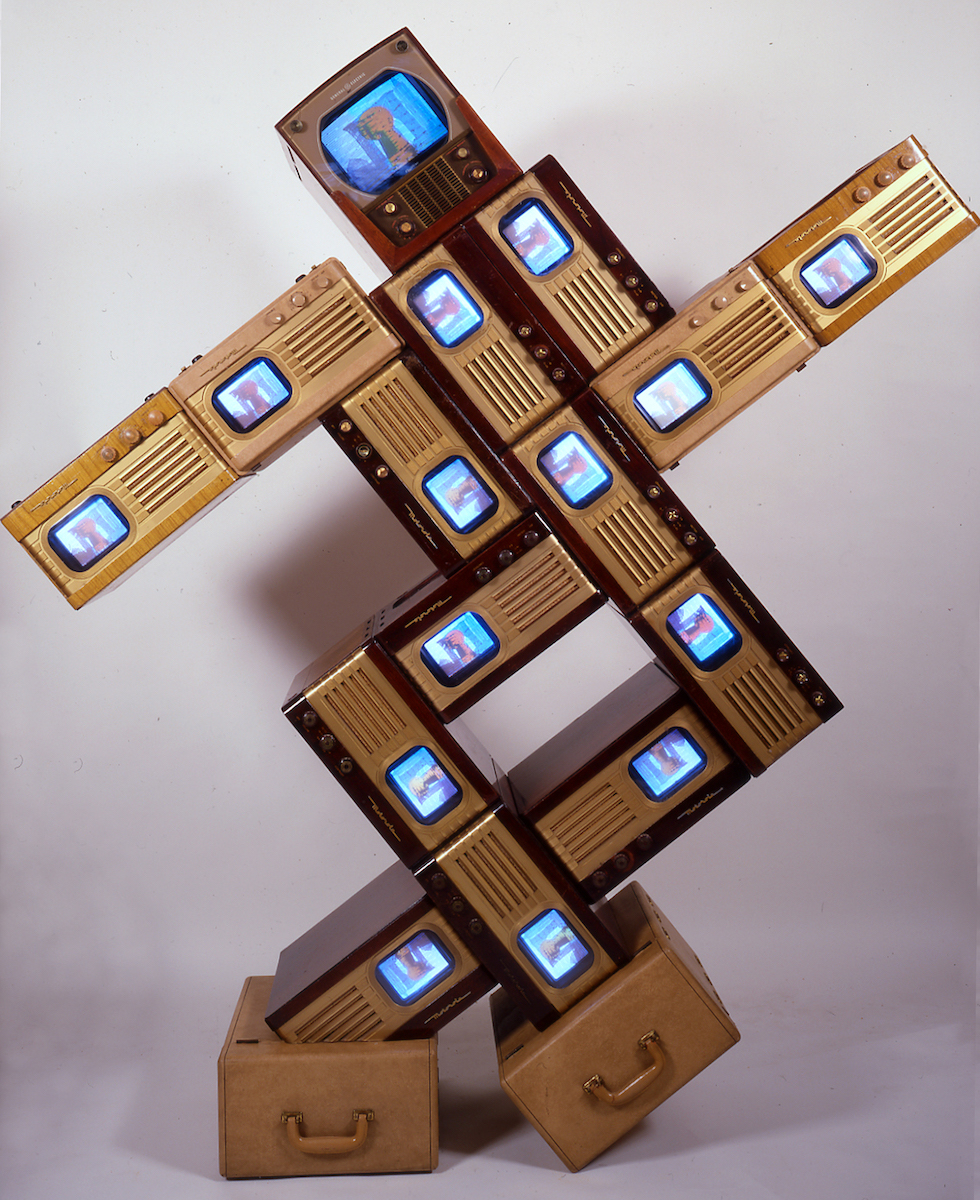

Nam June Paik, Untitled (TV Buddha), 1978; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Hakuta family; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Don Ross Many of Paik’s works relate to Zen Buddhism either directly or by inference. Although raised in Korea and Japan, where Buddhism was a part of the fabric of everyday life, his interest was not sparked until he learned of Cage’s enthusiasm for the practice. Paik’s iconic TV Buddha (1974) explores the intersection of technology and spirituality. A closed-circuit TV camera films an antique Buddha statue contemplating its own image on the screen opposite. As with much of his work, the playfully ironic content is balanced by an underlying sense of serious intention.

Paik collaborated with Shuya Abe on the Paik/Abe Video Synthesizer (1969-72) and manipulated video and TV monitors were at the heart of his practice from then on. TV Garden (1974) packs a large gallery with living plants interspersed with medium-sized TVs, all playing the same synchronized video feed, Global Groove (1973). With a vibe a bit like dipping into someone else’s acid trip, the soothing presence of the plants mellows out a mixture of rock music, interviews and exotic dance routines.

4. Nam June Paik, TV Garden, 1974–77/2002 (installation view, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam); Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Peter Tijhuis Collaboration is at the heart of much of Paik’s work, a practice that meshes nicely with his inclinations toward Buddhist thought. In 1964 he moved to New York, met Julliard-trained cellist Charlotte Moorman, and the pair jointly conspired to unite classical music and sex—feeling this was a rich vein of untapped potential. Paik composed scores for Moorman to appear topless, bottomless, and fully nude in Opera Sextronique (1967)—all while playing the cello—until the appearance of the NYPD disrupted the proceedings. This sparked the artist’s creation of an imaginative TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969). Paik also goes bare for an intimate moment where the two intertwine front to front as she plays him like a cello, Human Cello (1967).

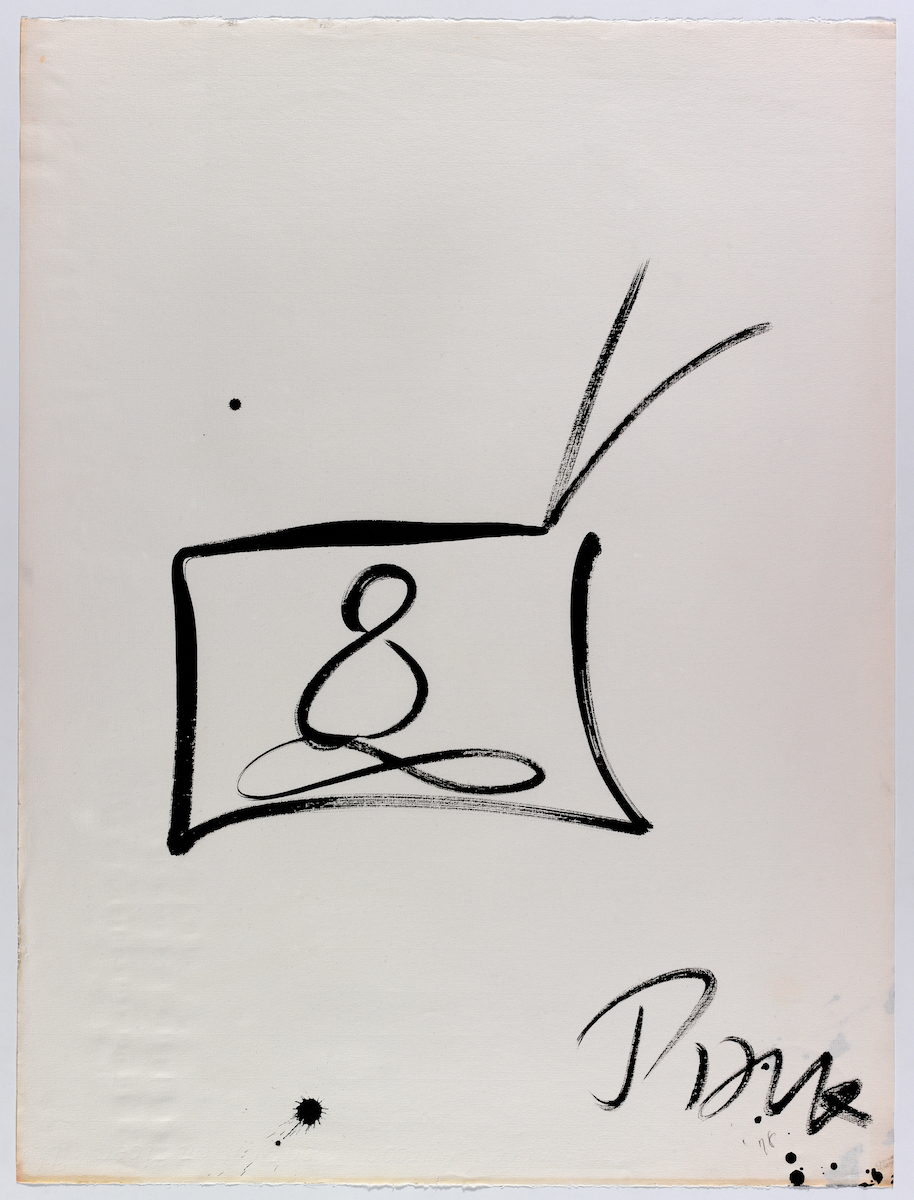

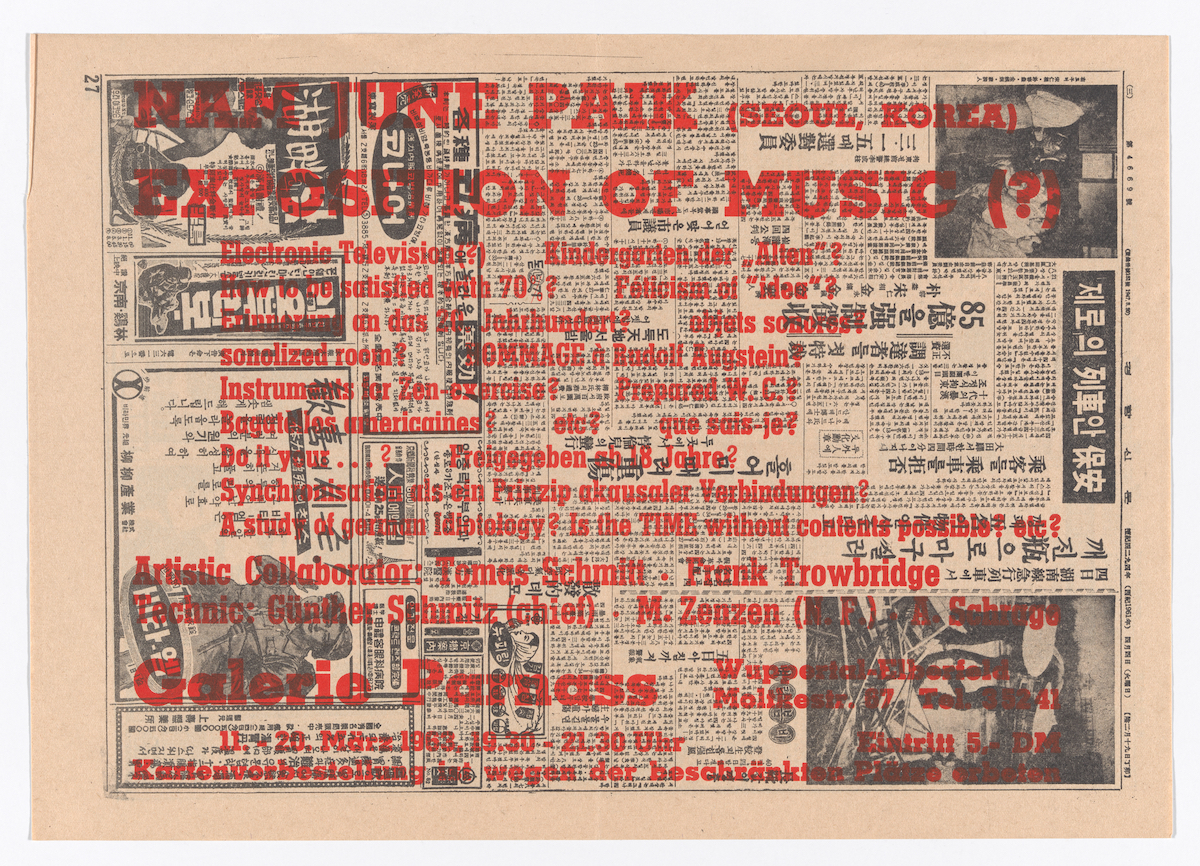

Nam June Paik, Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, 1963; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Hakuta family; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Don Ross Joseph Beuys made an impromptu appearance at Paik’s Exposition of Music-Electronic Television (1963) in Wuppertal, Germany. An upturned piano, part of the interactive sculpture, was destroyed by “the ever-serious and funny man, Beuys,” who chopped it to bits with an ax. Paik liked his addition to the event, and the two, both profoundly affected by the aftermath of war, later shared several notable performance collaborations, including Coyote III (1984) in Tokyo. Paik played the Moonlight Sonata, while Beuys contributed vocal improvisations. With shared interest in the Tartars, Beuys’ spinning the legend of his rescue by a band who wrapped him in felt and fat, and Paik envisioning himself as a modern-day incarnation of a nomadic Mongol horseman, they connected on a unique wavelength.

Nam June Paik, Merce / Digital, 1988; collection Roselyne Chroman Swig, San Francisco; © Estate of Nam June Paik Dance legend Merce Cunnigngham, known for his partnership with John Cage and collaborations with Warhol and Duchamp, also worked with Paik. Videos of Cunningham dancing are exploited to good advantage in a variety of works, including the figurative video assemblage, Merce/Digital (1988).

The climax of the show is Paik’s immersive Sistine Chapel (1993-3019) for which he co-won the Golden Lion for the German Pavilion at Venice Biennale in 1993. Forty projectors cover walls and ceiling with images. Dick Cavett, African dancers, David Bowie, Joseph Beuys and Lou Reed are among the subjects in a remarkable, dizzying video montage.

Paik, who passed in 2006, both anticipated and helped shape our contemporary image and video-driven world. His ability to shape-shift and thrive, and to create this groundbreaking work, is a testament to his resilience and inner vision.

Nam June Paik: A Retrospective

SFMOMA

May 8–October 3, 2021

-

William T. Wiley (1937–2021)

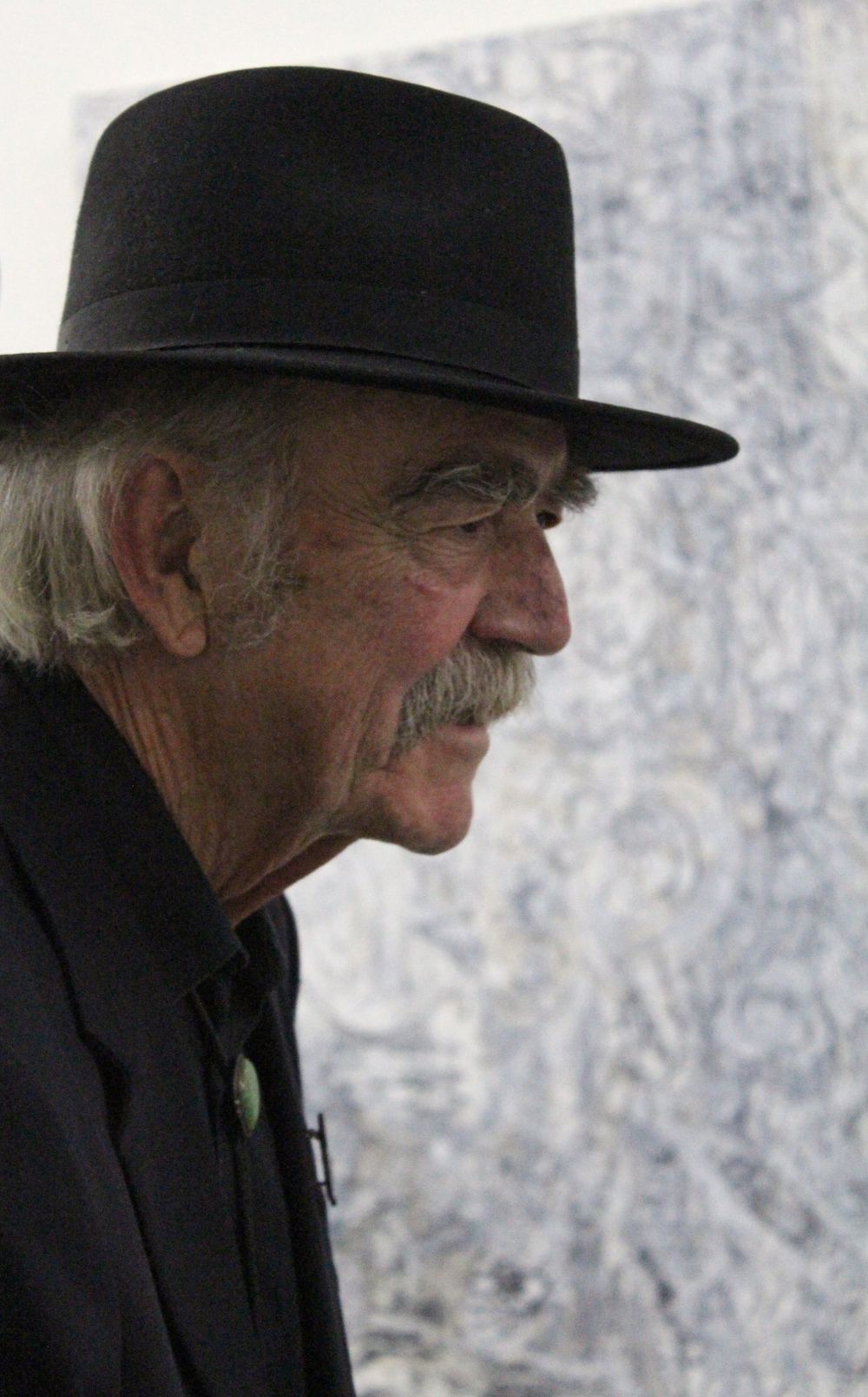

Paying tribute to an influential artistInfluential Northern California artist William T. Wiley passed away on April 25 in Greenbrae, CA. His combination of irreverence and spirituality so keenly reflected the spirit of our times, where we don’t know quite what to believe, but would all like to believe in something good. Like Wiley, many artists have worshipped at the altar of daily art practice, with a Zen-influenced mindfulness as their guide. Always a champion for the causes of social and environmental justice, and with an infectious, if occasionally groan-inducing, pun-intensive, sense of humor, Wiley was one of a kind.

William T. Wiley @ Hosfelt Gallery, 2015 William Thomas Wiley was born in Bedford, Indiana, in 1937, his family moving around a fair amount as his father, a construction foreman, took a succession of jobs. For a period they lived in Texas where they ran a combination gas station/diner, sometimes decorated with the young Wiley’s cartoons and drawings of horses. Later they settled in Richland, Washington where Wiley was encouraged by a prescient art teacher to pursue a career in fine art. This motivated his move in 1960 to the Bay Area to study at California School of Fine Arts, now San Francisco Art Institute. Wiley had a prodigious natural aptitude for art, and received a full scholarship to the school. Wiley also had a kind of low-key, hip disposition that was a good fit with the counterculture vibe of an era where the beatnik generation was giving way to flower children in San Francisco.

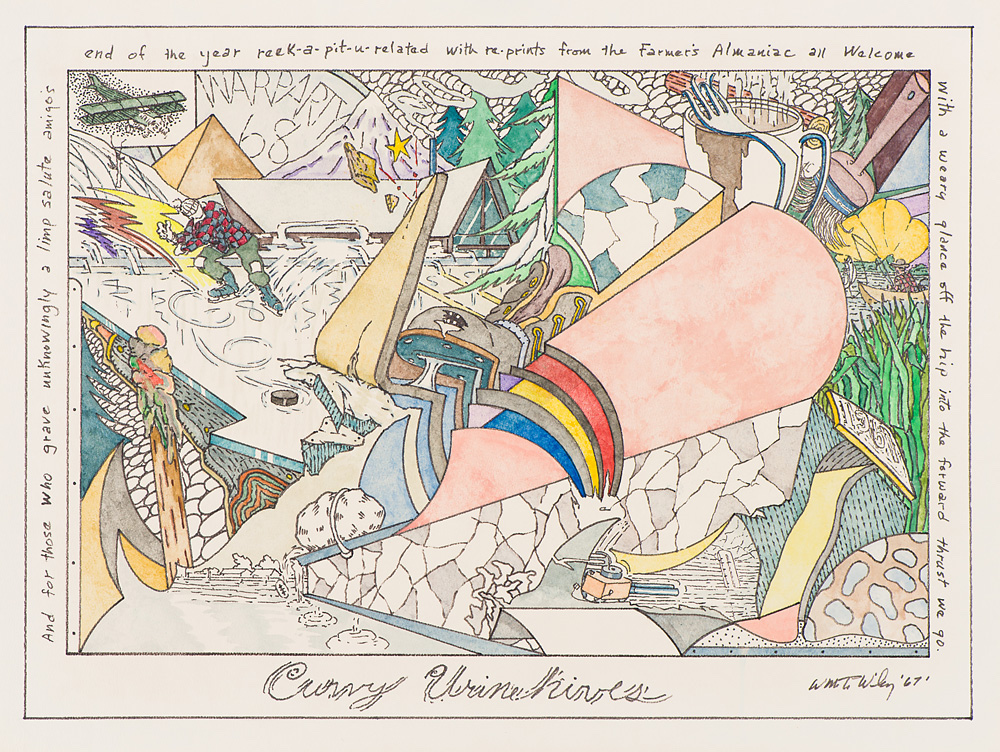

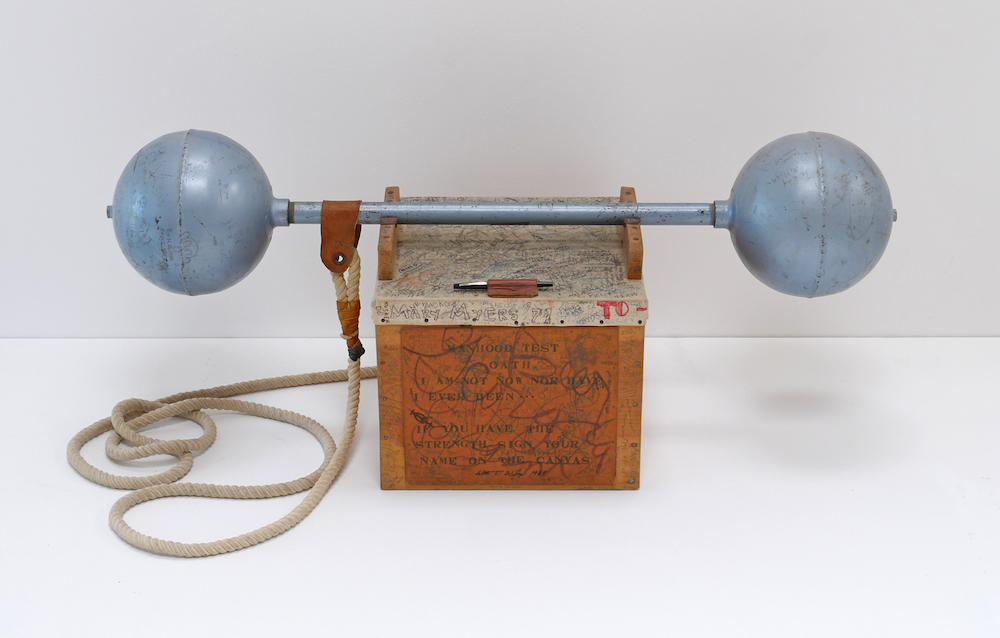

William T. Wiley, Manhood Test, 1969 San Francisco in the 60s was heavily influenced by the Beat scene, with writers like Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassidy and Lawrence Ferlinghetti reading their work in North Beach; words, music and art were closely intertwined. In addition to composing his poetic writing, which became enmeshed in the work, Wiley became part of a band, playing harmonica and guitar. With a breadth of media spanning painting, drawing, printmaking, assemblage and sculpture, one might well propose that his true calling was conceptual art. An enigmatic found object, Slant Step, acquired a talismanic significance in Wiley’s oeuvre. Former student Bruce Nauman, who later would himself influence the older artist, absorbed Wiley’s unspoken understanding that just about anything could, and would, be integrated into his art practice, and that the community of like-minded artists with whom he shared this journey were at least as important to him as the work itself.

William T. Wiley, Agent Orange, 1983 Almost immediately after graduating, in 1963 Wiley moved to Davis to accept a teaching job at UC where a critical mass of fine artist/teachers such as Wayne Thiebaud, Robert Arneson, Robert Hudson, Cornelia Schulz and Manuel Neri drew art students flocking to the sun-baked suburb west of Sacramento. The fiercely independent and quirky style of work created by Wiley and his cohorts came to be known as Funk Art, with its combination of casual and eccentric vibes, often displaying a bit of a rough-hewn esthetic. Venerable curator Peter Selz mounted a seminal “Funk” exhibition in 1967 at Berkeley Art Museum including Wiley, Joan Brown and Robert Arneson, among others.

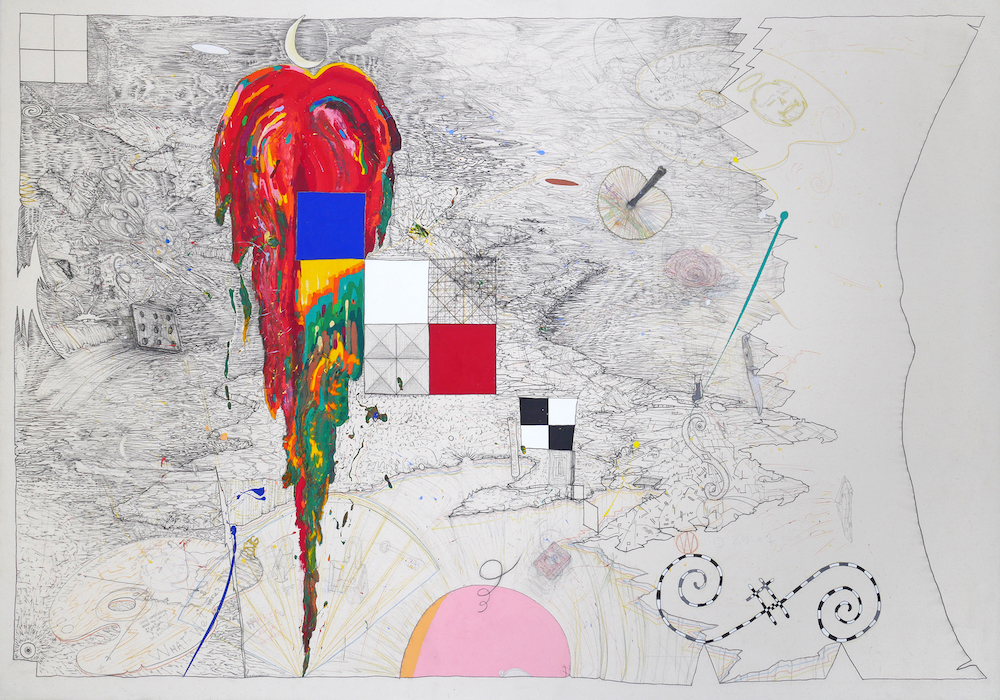

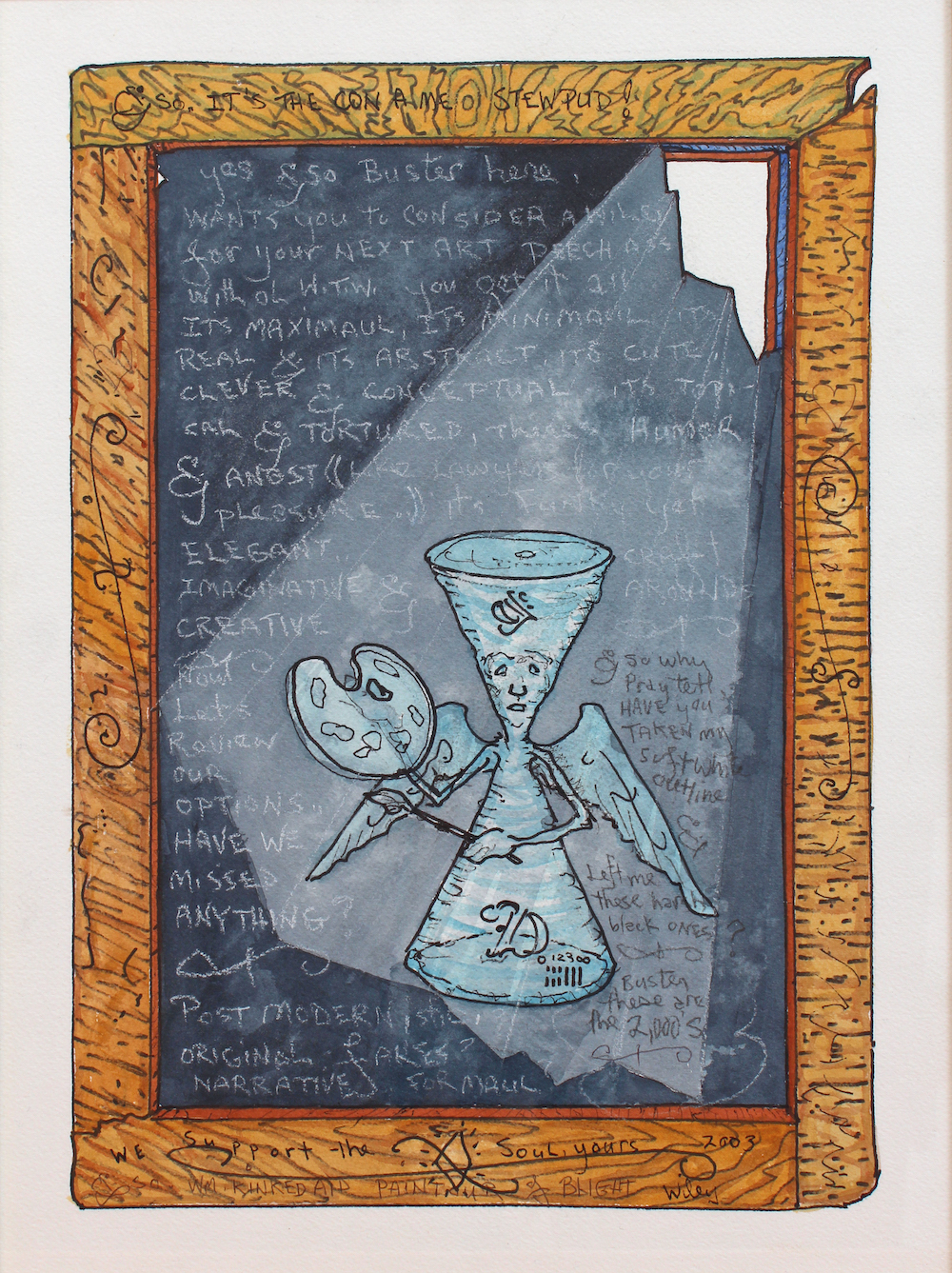

William T. Wiley, Buster in the Light, 2003 Wiley’s work often features an eclectic melange of Zen-inflected puns and spoonerisms, liberally scrawled across a variety of two- and three-dimensional surfaces. Often these take the form of landscape or still-life subjects, gardens with stumps or eddying streams, intertwining vistas of tools, still life objects, vines and plants, revealing his deep connection to nature and the kind of rural life where voluntary simplicity meets absurdist humor in an altered state of consciousness. With the ranches and farmlands of the rural west adjacent to where he and his cronies crafted meticulously-wrought, idiosyncratic artworks, his exhibition at SF’s Hansen Fuller Gallery in 1971 yielded a review in the New York Times where Hilton Kramer christened his style “Dude Ranch Dada,” a phrase that stuck.

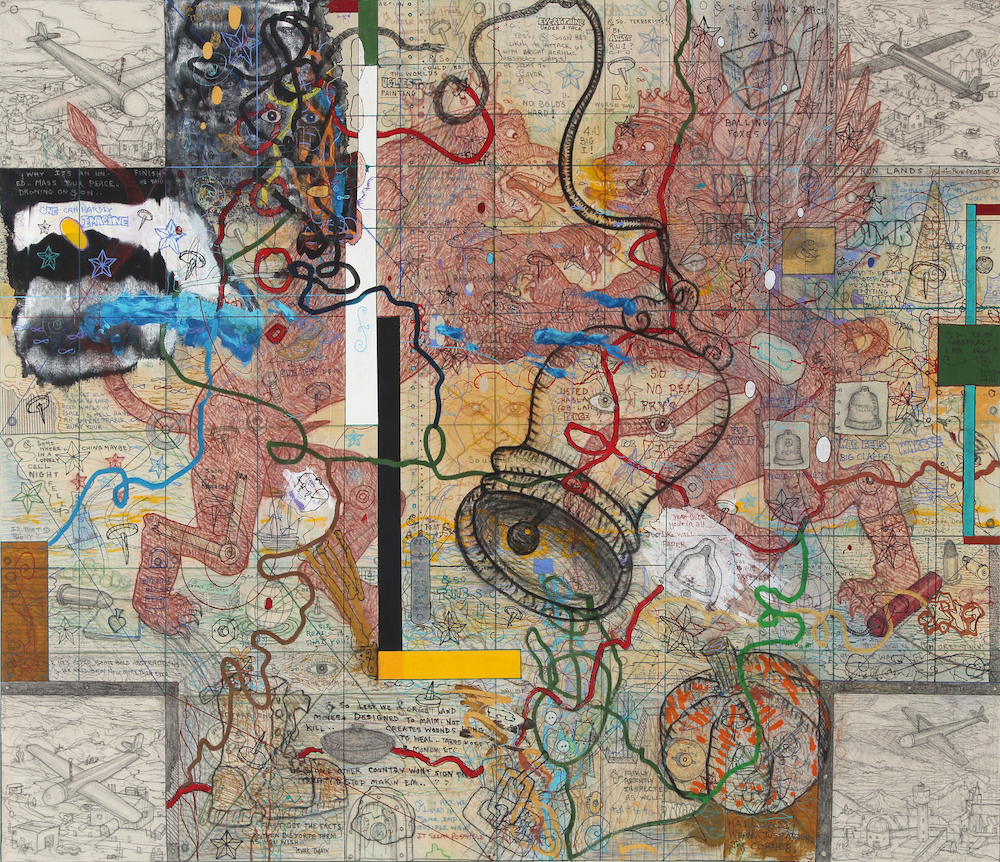

William T. Wiley, On the Left… We? Attempt a New Sign for the Palate. On the Right, Gold Man Sacks the World, 2010 Humor and jokes often propel the work, and Wiley constructed over the years a cast of characters that often act as autobiographical stand-ins. These include Mr. Unnatural, an affable, befuddled figure with handlebar mustache always wearing a wizard hat/dunce cap, and Buster Time, a winged hourglass who reflects on the fleeting nature of life. These characters could easily have stepped out of an underground comic, in fact, the truckin’ figure of R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural in Zap comix one clear source. His deep concern for mankind and the fate of the planet directly informed later works where he confronts existential issues such as war, pollution, racism, political malfeasance and general bad behavior, as well as an increasing preoccupation with his own mortality.

William T. Wiley, No Bell Prys for Peace with Predator Drone, 2010 A show of Wiley works curated from their collection is currently on display at SFMOMA. Wiley participated in numerous significant shows including Harald Szeemann’s “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form,” a 1969 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland that helped to define the Conceptualist and Minimalist art movements, the Whitney Annual and Biennial, two editions of the Venice Biennale, and Documenta V in Kassel, Germany. He had a major retrospective, “What’s It All Mean: William T. Wiley in Retrospect” in 2009 at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, DC, and a noteworthy, sprawling show at SF’s Hosfelt Gallery in 2014. The Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at UC Davis has a major exhibition of Wiley’s work scheduled for 2022, “William T. Wiley and the Slant Step: All on the Line.”

Wiley, who succumbed to complications of Parkinson’s, was predeceased by his younger brother, Charles, an artist at Industrial Light and Magic in San Rafael. He is survived by his wife, Mary Hull Webster of Novato, ex-wife Dorothy Wiley of Forest Knolls, his sons Ethan Wiley of Forest Knolls and Zane Wiley of San Rafael, as well as four grandchildren. Innumerable former students and colleagues also mourn the loss of this iconic figure.

-

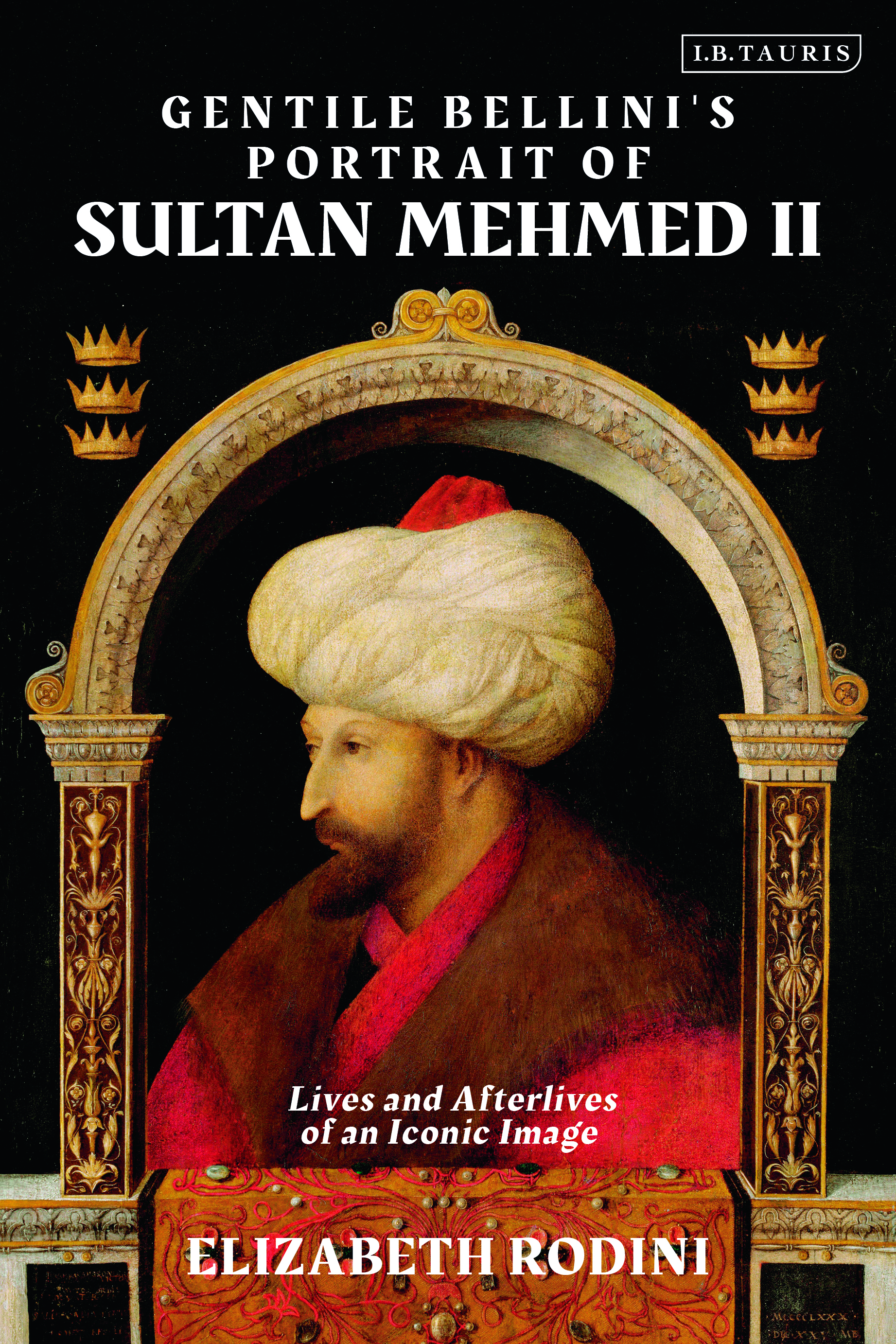

Book Review: Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II By Elizabeth Rodini

ABJECT OBJECTElizabeth Rodini’s Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II (2020) landed on my radar through meeting Rodini last year at the American Academy in Rome, where she is the Andrew Heiskell Arts Director. Rodini’s recent object biography investigates a number of intriguing and complex issues. Gentile Bellini, brother of the better-known Giovanni, was a Venetian artist. In 1479, he was commissioned to travel to Istanbul to paint a portrait of the Sultan, Mehmed II. This Renaissance portrait of an Ottoman sultan has gained a broad mystique, its legend perhaps eclipsing the actual substance of the canvas itself.

We may follow Rodini into the subterranean vaults of London’s National Gallery, where she finally encounters the portrait she has been exhaustively researching for so long …in a state of neglect, an object so altered and eroded as to bear little resemblance to its original state. This abject object had been the focus of intense strife and controversy, fought over for centuries.

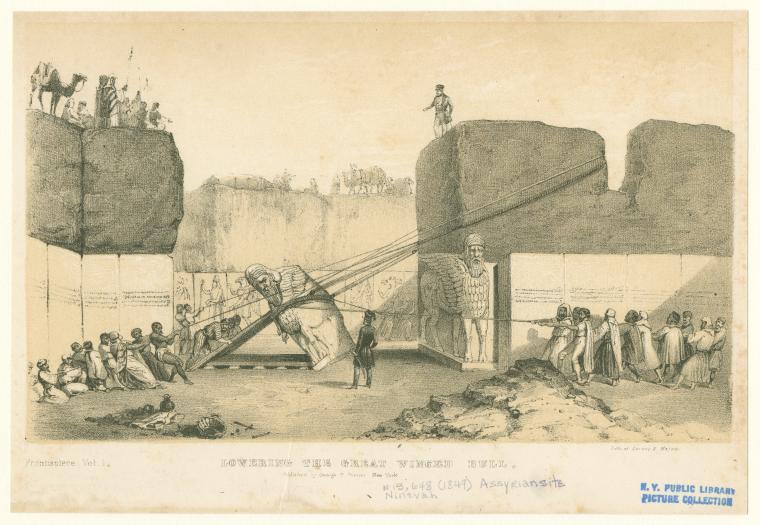

Lowering the Great Winged Bull, lithograph, frontispiece to Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, (London, 1849), The New Your Public Library, Digital Collections. Rodini brings this ostensibly dry and academic subject to life with the intensity of a gripping mystery novel…”Who done it?”

Cultural patrimony—the premise that artworks belong in the culture, often the country, where they were made—was a budding idea in 1912 when the owner of the painting, Enid, widow of collector and archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, passed away. The Layard collection, then housed in a palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal, was willed to her nephew, and London’s National Gallery. Before those parties could resolve who might have rights of ownership, they needed to get the painting to England—no small feat with Italy clinging to its treasured art objects.

This question of individual’s rights of ownership is a challenging one: Is it better to support the claims of individuals’ (or institutions) to private ownership of artwork, or will the broader good be served by placing the artwork in a setting deemed more culturally appropriate?

The Elgin/Parthenon Marbles are the “litmus test” for this issue, according to Rodini. Lord Elgin brought them from Greece to the British Museum in the early 19th century, where they have now resided for over 200 years. Greece, reasonably arguing that they were looted from the Parthenon in Athens, demands their return. The dispute has raged for centuries; Byron was among the first to condemn the looting. Once this is eventually settled, it may tip the scales for similar repatriation cases across the globe.

After James Fergusson, color lithograph, The Palaces of Nimroud Restored, color lithograph in Austen Henry Layard, The Monuments of Ninevah, 2nd Series (London, 1853), pl. 1. The New York Public Library, Digital Collections. Rodini takes a measured stance overall, weighing the value of the universality of priceless antiquities against the need to redress past injustices. Her description of studying an image in 2015 of an Assyrian winged bull in the British Museum, concurrent with reading news stories of ISIS defacing with power tools a nearly identical ancient sculpture in Iraq as part of a purge of imagistic artwork, definitely provides food for thought. Still, no excuses can be made for the colonialist and Orientalist impulses of these early plunderers, and repatriation will no doubt be one of the key challenges facing museums as they research the provenance of objects in their collections.

Rodini’s thoughtful work offers us an eye-opening window into many enticing, interwoven and labyrinthine realms.

Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II:

Lives and Afterlives of an Iconic ImageBy Elizabeth Rodini

224 pages

I.B. Tauris

-

8-bridges

Connecting the Bay Area and Beyond[et_pb_section][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text]Like many of us, I have spent much of the past nine months or so huddled in front of my computer. One day, an email arrived that really caught my eye. It was from 8-bridges—an organization I had never heard of—inviting me to save the date for a panel discussion featuring the directors of three cutting-edge Bay Area arts venues: Julie Rodrigues Widholm, the new director of UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), Alison Gass, who has assumed leadership at the Institute of Contemporary Art San José (ICA) and Jay Xu, Director of the Asian Art Museum since 2008.

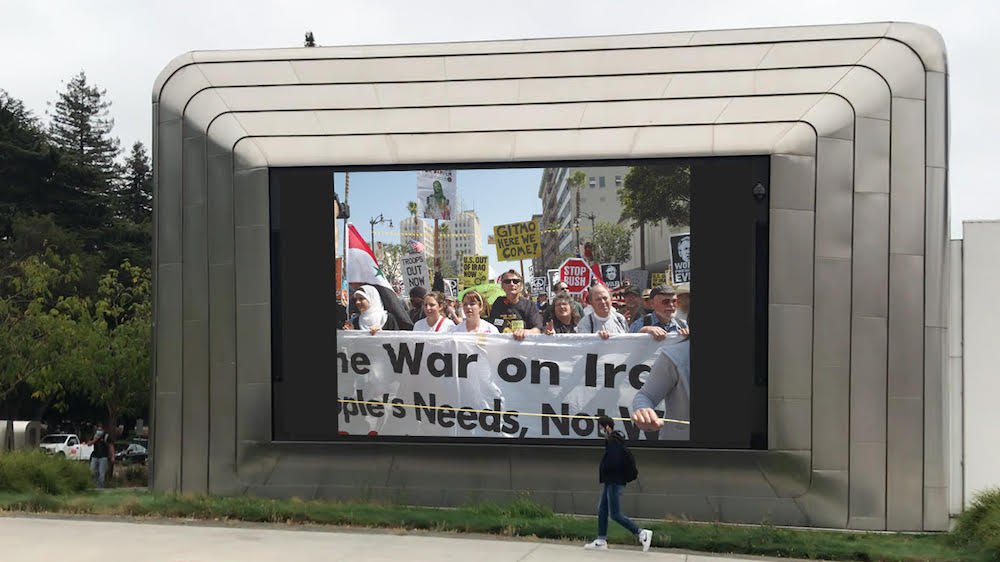

With these museums unable to open their doors to visitors these days, all have had to become very creative. Xu referred to “turning the museum inside out” when describing a trio of murals visible from the street, all newly created by Asian American feminist artists. Gass turned the entire exterior of the ICA into an exhibition space with a message aimed at getting out the vote. And Widholm is excited by the potential of a large outdoor video-projection screen, recently used to display photographs by Catherine Opie. This was the first in a series of three terrific panel talks, each featuring a trio of diverse museum directors.

Catherine Opie, Political Landscapes displayed on BAMPFA’s outdoor screen, 2020. Photo by Dave Taylor, courtesy of BAMPFA. So what is 8-bridges, the driving force behind the panel discussion? Named for the eight bridges connecting the Bay Area, it is the brainchild of a group of SF-based art leaders whose casual conversations evolved into a new online platform to increase the energy and vitality of the Bay Area arts scene in COVID times. The founding committee members are Claudia Altman-Siegel, Kelly Huang, Sophia Kinell, Micki Meng, Daphne Palmer, Chris Perez, Jessica Silverman, Elizabeth Sullivan, and Sarah Wendell Sherrill. Most of these are gallerists, running some of the best and brightest venues in SF.

I spoke with Kinell and Silverman, as well as Altman Siegel gallery Director Becky Koblick. The whole concept focuses on the idea of collaboration, and the premise that the best way to support the Bay Area art scene is by selling artwork. Kinell explained that 8-bridges evolved over “many weeks of conversations” between a group of colleagues, and involved many “minds and voices.” Koblick concurred: “Since we were unable to travel as much—which is such a huge part of our industry, to meet new artists and clients—we wanted to work together in the community to make sure we still had a voice during this time.”

Echoing the 8-bridges concept, the platform rolled out a schedule of online exhibitions by eight galleries presenting eight works each month. Another key feature of the platform is to feature an alternative space or institution each month, showcasing its mission and encouraging viewers to donate.

Alex Olson, Egg, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco. Sophia Kinell, the regional lead of the San Francisco branch of Phillips contemporary auction house, spoke with me of a recent New York auction: ”It was our best ever. We set major records for artists like Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Amy Sherald, Jadé Fadojutimi, and Vaughn Spann—an incredibly diverse roster of artists.“ Kinell said that “With 8-bridges, we are putting our muscle behind the institutional beneficiary. In the inaugural month of October, this was the Museum of the African Diaspora; in November, Creative Growth (Art Center), and in December an institution near and dear to my heart, the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito.”

While 8-bridges is fresh to the Bay Area scene, it shares a concept implemented successfully in other locales. Similar ideas were born in Los Angeles’ GALLERYPLATFORM.LA, and in New York, where megadealer David Zwirner launched Platform: New York. These online platforms are currently extensions of the gallery system but could certainly evolve into something else, with even more potential to expand the ways we interact with art. Artists increasingly have the ability to show and potentially sell their own work online as well. The challenge lies in making the experience richer and more authentic.

ICA San José installation view of Amir H. Fallah: The Facade Project, 2020. Photos by Impart Photography. A theme emerging across the board in the Zoom panel talks is this shift to the virtual. When I spoke with Widholm she emphasized that at BAMPFA, “Our staff has done a brilliant job pivoting toward digital programming… primarily with our virtual cinema programs streaming cinema accompanied by panel discussions and live interaction with filmmakers and people behind the scenes.” Another recurring theme is greater engagement with the local community. Mari Robles, incoming director of the Headlands, alluded to a shift in its involvement with local artists: the former “affiliate artist” program dissolved, to be replaced by something more integrated with its internationally acclaimed resident artist program. Finally, an idea that seems particularly urgent is creating internship programs for young people, particularly for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) youth for whom a career in museum work might seem off the radar. Monetta White, Director of the Museum of the African Diaspora wondered aloud, “Why did it take George Floyd for us to begin having these conversations?” With the reset on our cultural institutions provided by COVID, and magnified by the racial justice movement, it’s obvious that no one really expects, or wants, to go back to “business as usual.”

A key piece not only to 8-bridges, but to the future as an arts community, is collaboration, with various parties working together to share resources and promote art. While the impetus behind the new platform is to survive the COVID crisis, it also reflects a certain zeitgeist: the need for change in the art world as a whole. As sky-rocketing rents and exorbitant art fair fees have increasingly priced the smaller brick-and-mortar galleries out of the market, for many the shutdown may be the last straw.

Installation View of Sadie Barnette, The New Eagle Creek Saloon, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2019. Courtesy of the Artist, Charlie James Gallery, and Jessica Silverman. So how will emerging artists bridge the gap from obscurity to recognition? It’s great to hear brainstorming on ways in which galleries and museums, even auction houses, may work hand in hand with artists, creating opportunities and bonds that had not existed. Alongside these institutional shifts, one hopes that a new spirit of cooperation, rather than competition, may arise within the broader art world. With a teeming population sharing diminishing resources, perhaps it’s time to rethink some of our longstanding assumptions about images and objects.

Will 8-bridges disappear once we are able to return to “normal”? As Jessica Silverman says, “I think it will continue. I really believe that virtual and online programming alongside the physical is going to be the new paradigm. I think that it’s here to stay.” With the reshuffling of the deck when things reopen, many changes loom ahead. Art galleries will need to adapt and evolve, and in many ways, that’s a good thing.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section] -

Ramekon O’Arwisters

Fabric and Ceramics Fits His WorldGrowing up as a queer Black child in the Jim Crow era South, Ramekon O’Arwisters and his family had many barriers to overcome. His grandmother, recognizing that the young boy was “a bit of a hot mess,” one day called him over and invited him to work with her on her quilt. While already carefully planned out, by allowing him to break the pattern with fabric and thread, she validated his choices to break patterns in other aspects of his life.

O’Arwisters obtained a Master of Divinity degree from Duke University, but at that time the ministry had not embraced gayness, and he did not want to remain closeted. Instead, he moved to Japan and lived in Tokyo for the next five years. Returning to the States, he settled in San Francisco, working as an artist while holding curatorial positions.

Ramekon O’Arwisters, Cheesecake #2, 2019 In 2011 he had an epiphany, realizing that “traditional materials, oil paint and canvas, did not equate to my experience. That was a Western European tradition.” What resonated with Ramekon was fabric. After frustrating years courting acceptance from galleries, he decided to instead give that very thing he sought—acceptance—to others. Thus his social practice work, the Crochet Jam, was born.

For the past decade, O’Arwisters has transported heaps of colorful fabric—along with handcrafted, oversized wooden crochet hooks—to community centers, galleries and hospitals around the country. He believes the important aspect of these events is giving agency to others in a nonjudgmental space, much as his grandmother empowered him to accept who he was and to feel loved and valued.

Ramekon O’Arwisters Portrait. In 2016 during his Recology residency, he stumbled across shattered ceramics at the SF dump, sensing a deep connection to the broken shards of pottery. Soon, he began combining them with fabric and the crocheting process. A strong show of this work, “Mending,” was presented at Patricia Sweetow Gallery in 2018.

O’Arwisters’ latest body of work, “Cheesecake” is flashier, with brightly colored fabrics, hot pink lace, gold tassels. In collaboration with the ceramic department at Cal State Long Beach, he now recycles broken pieces from their “shard yard.” As objects, his medium-scale sculptures nearly defy description, their complex geometry—a tangle of knotted fibers and razor-sharp edges—convey an unsettling mixture of beauty and danger. In an alchemic reaction, the two materials of fabric and clay are forged into a new union, a bond that adheres through sheer force of will.

Ramekon O’Arwisters, Cheesecake #6, 2019 As we finish our conversation, the artist pauses, then shares, “you know, you mentioned that word, ‘democracy,’ and people tell me that we’re living in one, but I don’t see it. I don’t know what it’s like to live in a democracy.” He views his work as taking place in a context of racism as a permanent state of our country. Driven by this deeply felt and unchanging understanding of injustice, he asks, “How can I turn my pain and anguish into something that’s beautiful and profound?”

Photos by David Schmitz, courtesy the artist & Patricia Sweetow Gallery.

-

Profile: Robert Ortbal

Rather than pursuing variations on by now familiar themes, the Sacramento and Emeryville-based Robert Ortbal follows a path that may well twist into an entirely different dimension. Recently you might find the serious and intellectual Ortbal wearing an oversized dog head, or riding a bike while in the guise of a giant rabbit. His sculptural art practice has gradually evolved to focus on “eccentric behaviors” performed in wearable artwork.

Robert Ortbal in his studio. All of us have recently been thrown into a Twilight Zone universe, and when Ortbal’s recent show “Marmalade” at Sanchez Art Center in Pacifica was, like so many exhibitions, cut short that also meant no artist talk—or did it? Ortbal, along with guest curator and former Oakland Museum Chief Curator Phil Linhares, decided to hold the talk online, via a Zoom meeting. They joined us in the form of talking heads, exchanging thoughts and alternating with intriguing images of the exhibition. A followup call with the artist allowed for a closer degree of human connection, speaking one-on-one in real-time.

Robert Ortbal, Midnight Sunset, 2015 Ortbal’s sculptural practice has always raised more questions than it answers, his installations populated with irregular geometric or biomorphic objects that writhed and crept across walls, like organic forms mutated in the lab. There remain vestiges of the scientist in Ortbal, although he allows that this was more appropriate for his earlier bodies of work, ones evoking underwater creatures or crystalline formations. His unique vocabulary remains, “my language and my thinking take place in the bending of a wire, or the coating of a surface.”

Robert Ortbal, Neverland, 2015 Growing up in the South Bay town of Campbell, a working-class suburb back before the tech boom transformed Silicon Valley, Ortbal explained to me that “you could roam somewhat feral” as a boy. Family expectations were that he followed a traditional path, his dad’s military background had led to a career as a mechanic for the airlines, and he took a dim view of his son’s artistic ambitions. Undergrad school at SF State, where Ortbal focused on ceramics, was one thing, but attending grad school at UC Davis, where noted faculty such as band Mike Henderson propelled him farther down this unconventional path, was quite another. As his father grew to appreciate the seriousness of Ortbal’s work, and just how hard he worked at it, “we eventually made peace.”

Robert Ortbal, Dumb Bunnies, 2018 Since 2003 Ortbal has been on the faculty at Sacramento State University. Each year, the Crocker Art Museum’s education department hosts U-Nite, a community outreach event. The SSU art professors are strongly encouraged to participate, however their artwork is given the short end of the stick, painters for example asked to display work on an easel in the hall. In response, Ortbal came up with an unorthodox idea. One day, as he explained to Linhares, while visiting a costume shop, he was confronted by a wall of bunny rabbit head masks. “It stuck with me,” he explained, as he devised a plan to bring 20 Dumb Bunnies (2018), rabbit-headed artists and arts professionals, to the Crocker event. They cycled over from the artist’s house, an alarmed woman they passed on the street remarking, “this is not good…” Upon arrival, they paid their way in with carrots. If Ortbal’s intention was fairly benign, not everyone was so amused, “Pissed some people off big time,” admits the artist who insists it was meant as a humorous, absurd action more than a political one.

Installation view of Marmalade. Ortbal’s most recent exhibition “Marmalade,” featured sculpture, drawings, photographs and video. In one corner of Sanchez, a collection of objects were clustered on a gray structure composed of square platforms positioned at various heights on spindly supports; Ortbal and Linhares discussed the way this finessed the need for a “forest” of intrusive pedestals, inventive installation choices have long been a key element in the work. Medium-scale sculptures consist of assorted geometric forms, each a conglomerate of segmented parts, one of lengths of cylindrical hunks of something, perhaps foam, others more rectilinear. As with earlier works, the objects gain interest in the textural encrustations applied to the surface, paints and other coatings slathered roughly here, blobbing like fungal growths there, a low-key palette of black, white and grey predominating.

Robert Ortbal, Crystalline Jester, 2015 Crystalline Jester (2015), a large multi-faceted object in earth tones, punctuated by triangular planes of red, hovers imposingly mounted on a wooden dowel. Like many of these objects, it can be worn. As the wearable art sits, inanimate, there is a sense of anticipation. Video and photo elements were virtually impenetrable in the Zoom presentation; they apparently include brief iPod footage of the artist in Bad Dog (2019) persona, peeing on the wall of the Crocker, along with Polaroids of other “eccentric behaviors”—Ortbal prefers to display these intimate in scale, to draw the viewer in.

Installation view of Marmalade. Ortbal emphasizes that the “work is shifting and embracing the idea of ambiguity and emptiness.” His work has always triggered multiple sensations and associations beyond the verbal, beyond ready comprehension. Trying to put a finger on the misty place in which these constructions reside, we discuss the “collapse of truth” and the absurdity of the past three years that informs them, along with our transition to the new virus era. The recent work presents a new mindset to adapt to—less Richard Tuttle and more Nick Cave. Ortbal’s plans for the future involve a new body of sculptural work including tiny figures absorbed into abstract environments, an eccentric world in miniature. While serious about the work, Ortbal’s practice is also imbued with a strong sense of humor, and, as Linhares said, “a pleasantness,” something we can all use more of these days.

-

Ellen Sebastian Chang, Sunhui Chang and Maya Gurantz

“How to Fall in Love in a Brothel” offers a mix of the experiential and the conceptual, expressed as an interactive sculptural installation and an HD video. A collaboration between artists Ellen Sebastian Chang, Sunhui Chang and Maya Gurantz, the idea of a “brothel” takes on a larger definition as an arena where relationships and intimacy may only be possible within the bounds of a culture based on commerce.

The Shoji Room (2019) is a physical manifestation of, and a metaphor for, the idea of intimacy, the full expression—and entrance—only available to those who purchase “Intimacy Hours.” Ritual floor cleaning, cot making and the consumption of corn tea and Hershey’s chocolate are all detailed in the Intimacy Kit (2019). Cell phones are prohibited, the artists curating an experience where a couple interact solely with each other within this small space for sixty minutes, a luxury, or perhaps a challenge.

Ellen Sebastian Chang, Sunhui Chang and Maya Gurantz, (detail) Shoji Room from the installation: How to Fall in Love in A Brothel, 2019. Fabricated by James Anderson. Photo credit: John Wilson White, courtesy Catharine Clark Gallery. Beautifully constructed of Baltic birch plywood, walnut and Kozo Shoji paper, the room is bathed in hues of red or purple light. Small holes are created in the paper as per the artists’ instructions, allowing viewers to peek into the interior space—referencing a rural tradition in South Korea where newlyweds consummate their marriage in a room with shoji panels, where villagers silently create peepholes in the paper with wetted fingers. Peeping in while a reclined couple whisper together definitely feels transgressive.

The video piece and the entire collaborative project were inspired by a script written by Sunhui Chang in 2017, a fictionalized memoir of his family history in Korea. In it, a couple meets in an abstracted 1950s shoji room, where a girl has prepared food. At one juncture, the young man says “I don’t like the idea of you pleasuring other men.” She replies dryly, “Do you think I cook for just anyone?” A Hershey’s chocolate bar, a type of currency in Korea at the time, provides a moment of rapture.

BOX BLUR programming, in its fourth year at the gallery, extends ideas into performances held within the exhibition. Dance and spoken word performances one evening were by dancer/choreographer DaEun Jung and the multi-disciplinary Maya Gurantz, the latter’s punctuated by impassioned ripping of her clothing as her narrative intensified.

What is most compelling about the exhibition is the way it teases out a response from the viewer, the allure of the forbidden creating desire. The exhibition is also remarkable in its ability to evoke a nostalgic sense of time and place, that of mid-20th century Korea, while simultaneously exploring 21st-century concerns couched in an ironic tone. What, indeed, is the price of privacy?

-

Ann Weber

When Ann Weber began working on her current series of monumental sculptures made from recycled cardboard, vitriolic rhetoric about constructing a border wall dominated the news. Trying to grapple with the idea, her research led her in a surprising direction, to Pink Floyd’s 1979 rock concept album which addresses fear and domination, The Wall. A song about abusive schoolmasters appears on the album, and Weber adopted its title, “Happiest Days of Our Lives,” for her recent exhibition at Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

Weber presented large scale freestanding and wall-mounted works created by using her unique technique of bending, twisting, weaving and stapling thick strips of cardboard. The artist mines alleys and trash heaps for interesting boxes, and has taken her dumpster-diving routine on the road to locations such as Rome and Beijing, where she has held artist residencies. Weber draws ideas from the architecture and scenery of the San Pedro area where she now lives. The area has recently provided inspiration for murals and walls covered by the ornate shapes of Gothic-style gang graffiti.

Ann Weber, Installation view, Courtesy of Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco Gothic on Grand (Stick ‘Em Up) (2019) features a pair of sculptures standing about human height, the voluptuous forms of one countered by the angular forms of its more monochromatic partner. Weber always begins with a 2D shape, using the corresponding negative shape to construct the following work, so connections and intersections are a logical result. Weber’s work, with its woven, hand-made quality, springs from the foundation of craft, yet also inhabits the realm of formalism, Brâncusi’s spare modernist sculptures come to mind. The grid pattern created by the voids also speaks the language of Minimalism.

In the wall-mounted work, Weber expands this pairing into a multiplicity of connections, suggesting bonds to heal, rather than barriers to fracture. Happiest Days of Our Lives #22-27 features flowing, organic shapes, negative spaces of oval and teardrop shapes, flanked with spikier, more assertive forms ending in conical protrusions. Letters and fragments of text emerge. In HDOOL #18-21, Weber emphasizes color, stripes of brick orange, pumpkin, and turquoise, along with green gold, creating a joyous, heterogeneous, vibe.

Personages Poetry (2016), a pair cast in bronze, dominates the back room. With an economy of means, Weber suggests the tenderness and fallibility of human relationships, the bronze casting lending the work an element of greater gravitas. Still, the cardboard works retain the endearing marks of the human hand and glow with a warm patina of sun-baked cartons. Weber’s mastery of her unusual medium is so complete that each piece conveys a sense of irrefutable logic, that somehow it was destined to emerge in just this way. Her work reflects a belief in the power of the spirit to overcome adversity and divisiveness, and her enduring optimism is infectious.

-

ALAN RATH

Ever since man created robots, there have arisen ethical and moral questions regarding when and how they should be used. Isaac Asimov created the concept of the Three Laws of Robots in his 1942 short story “Runaround,” the first of which stipulated that a robot was under no circumstances to ever harm a human being. With sophisticated robotically controlled drones as an increasingly ubiquitous element of contemporary warfare, that idea didn’t quite take root. Thankfully, the flip side of the coin exists.

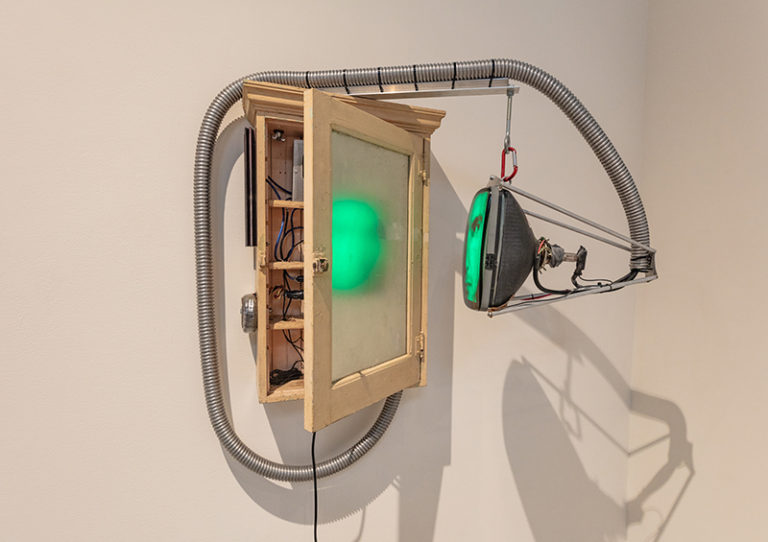

Alan Rath’s “Virtual Unreality” at San Jose ICA is a testament to the allure of the robot—it’s the most well-attended exhibition the ICA has mounted, ever. A retrospective sampling of Rath’s robotic sculptures fills two large gallery spaces with whirring, blinking and spinning contraptions. Rath migrated to the field of fine art from a background in engineering; he holds a BS degree from MIT. He has been making robots since the 1980s, and his enthusiasm for the world of wires, circuits and video monitors of assorted types is infectious.

Many of the works incorporate imagery of human features, lending them an anthropomorphic quality. Eyes or mouths hover on LCDs, or in earlier works, cathode ray tubes, bathed in vibrant shades of green, pink or violet. Optical Cylinder V (2016) stands 6-feet 6-inches, roughly human height; the trio of stacked LCD screens conveying a benign, vaguely space-aged presence. The increasing issue of surveillance in our lives is prevalent in many of these mechanical creatures. Rath displays a similar aesthetic to New York-based sculptor Tony Oursler, and to some extent with another notable engineer-turned artist, San Francisco’s Jim Campbell.

Alan Rath, Vanity (1992) collection of Tom Patchett, courtesy San Jose ICA. Birdcage (1985), the earliest work on display, houses a minute cathode ray tube in an old rusty cage. Unexpectedly, at random times it springs into action, making a loud, startling sound as it jerks down. The uncanny way in which the robots respond to motion creates an illusion of sentience. These robotic constructions are all an interesting blend of high- and low-tech, the futuristic elements and computer-driven electronics meshed with the funkier and more organic elements—feathers, plywood, found objects. Rath’s humor infuses other pieces with charm: a hot-pink feathery creation evoking a fan dancer, or pulsing electronic bouquets comprised of throbbing speakers.

In the larger room, the robots have an opportunity to command the space. The most dramatic of these, Absolutely (2012), at 15-feet-tall, features a circular configuration of elongated pheasant feathers, their tips nearly brushing the high exposed beams of the ceiling. The brown and white striped feathers lift, vibrate and quiver as we approach, once again seeming to come alive.

The enduring popularity of the horror genre demonstrates how much fun it is to be frightened, and certainly with the larger robots, as well as in the darker implications of the smaller ones, there is an underlying element of menace. But with Rath’s propensity for fun, using brightly colored components and whimsical allusions to nature or toys, these objects ultimately share elation and delight with the viewer.

-

Patricia Piccinini

“Inter-Natural,” the title of Patricia Piccinini’s solo exhibition, links two ideas, “inter” implying spaces between, and “natural” the realm of unspoiled nature. For over two decades, the Australian artist has been exploring just this liminal space, where nature meets nurture in biology lessons that are part obstetrics, part Frankenstein’s lab.

Entering the gallery, the first encounter, Unfurled (2017), is dramatic. A young girl in a blue denim dress sits, legs tucked under, in an upholstered chair. Her startled expression is echoed by that of a large tawny owl, perched on her shoulder. These figures are disarmingly lifelike, and one remains on edge, half-anticipating them to spring into motion. The hyper-realist sculptures of Duane Hanson, similarly unnerving, may certainly come to mind.

Throughout the exhibition, Piccinini returns to themes of fertility, sexuality and emotional attachment. She displays a particular obsession with the primal relationship that exists between mothers and children. In The Bond (2016), this devotion transcends obstacles up to and including difference in species. Here the “baby,” appalling yet endearing, has a human face, albeit with enlarged nostrils, seemingly runny nose, moist lips, wisps of blond hair trailing across its forehead. Rolls of baby fat under the chin morph into a grotesquely flabby, misshapen body. One’s mind may race to construct a backstory, envisioning scenarios in which such beings might actually gestate and come to life. Perhaps not so far off: while transgenic animals—ones genetically modified through recombinant DNA technology—have been around since the 1970s, it was just in 2018 that Chinese researchers announced the creation of the first genetically modified human embryo, causing quite an uproar over the ethical and moral implications.

Patricia Piccinini, The Couple (detail) (2018), courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco. Most striking, and intimate, is the tour de force installation The Couple (2018). The viewer enters a large tent to find a humanoid pair embracing on a small cot, beneath a sleeping bag. Both figures have elongated faces and snout-like noses, suggesting muzzles. Their fingers and toes bear wicked talons. The male, with profuse reddish hair, and a bit like a werewolf, nestles in the crook of the female’s neck. Her eyes are wide open, with a preoccupied look. One may identify strongly with the creatures, with their failure to fit in, a potentially tragic circumstance. But in Piccinini’s world, perhaps the human beings are the monsters.

The Naturalist (2017), resembling a small sea lion, features tiny feet joined at the base that splay to form flippers. These minute appendages may evoke disturbing thoughts of the practice of footbinding. Perhaps the resemblance is unintentional, yet the impact of man’s persistent desire to “improve” his fellow beings, often those who are powerless to object, lies at the heart of the matter. Clearly, among the numerous challenging issues raised in Piccinini’s work are ones of standards of beauty and cultural acceptance, her resilient mutant models consistently triumphing over adversity. In a more homogeneous future, perhaps the sci-fi dilemma of inter-species or anti-cyborg prejudice may someday become a fact of life. Piccinini’s remarkable work certainly makes such a vision believable.