Ever since man created robots, there have arisen ethical and moral questions regarding when and how they should be used. Isaac Asimov created the concept of the Three Laws of Robots in his 1942 short story “Runaround,” the first of which stipulated that a robot was under no circumstances to ever harm a human being. With sophisticated robotically controlled drones as an increasingly ubiquitous element of contemporary warfare, that idea didn’t quite take root. Thankfully, the flip side of the coin exists.

Alan Rath’s “Virtual Unreality” at San Jose ICA is a testament to the allure of the robot—it’s the most well-attended exhibition the ICA has mounted, ever. A retrospective sampling of Rath’s robotic sculptures fills two large gallery spaces with whirring, blinking and spinning contraptions. Rath migrated to the field of fine art from a background in engineering; he holds a BS degree from MIT. He has been making robots since the 1980s, and his enthusiasm for the world of wires, circuits and video monitors of assorted types is infectious.

Many of the works incorporate imagery of human features, lending them an anthropomorphic quality. Eyes or mouths hover on LCDs, or in earlier works, cathode ray tubes, bathed in vibrant shades of green, pink or violet. Optical Cylinder V (2016) stands 6-feet 6-inches, roughly human height; the trio of stacked LCD screens conveying a benign, vaguely space-aged presence. The increasing issue of surveillance in our lives is prevalent in many of these mechanical creatures. Rath displays a similar aesthetic to New York-based sculptor Tony Oursler, and to some extent with another notable engineer-turned artist, San Francisco’s Jim Campbell.

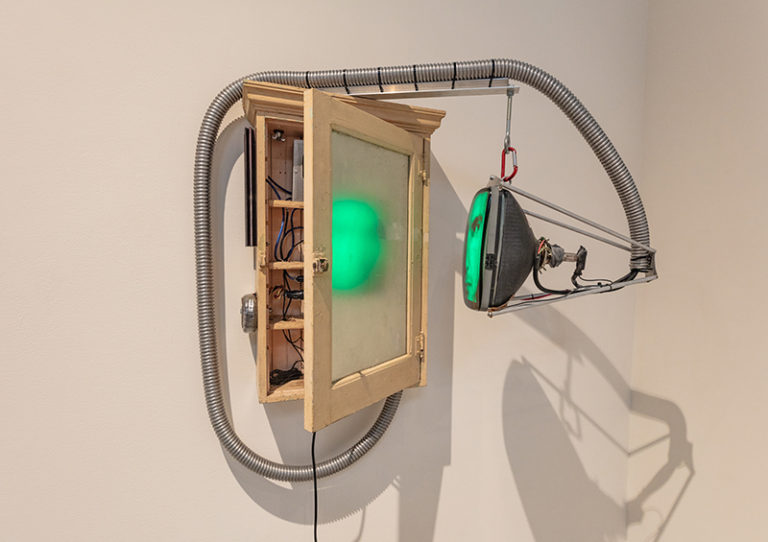

Birdcage (1985), the earliest work on display, houses a minute cathode ray tube in an old rusty cage. Unexpectedly, at random times it springs into action, making a loud, startling sound as it jerks down. The uncanny way in which the robots respond to motion creates an illusion of sentience. These robotic constructions are all an interesting blend of high- and low-tech, the futuristic elements and computer-driven electronics meshed with the funkier and more organic elements—feathers, plywood, found objects. Rath’s humor infuses other pieces with charm: a hot-pink feathery creation evoking a fan dancer, or pulsing electronic bouquets comprised of throbbing speakers.

In the larger room, the robots have an opportunity to command the space. The most dramatic of these, Absolutely (2012), at 15-feet-tall, features a circular configuration of elongated pheasant feathers, their tips nearly brushing the high exposed beams of the ceiling. The brown and white striped feathers lift, vibrate and quiver as we approach, once again seeming to come alive.

The enduring popularity of the horror genre demonstrates how much fun it is to be frightened, and certainly with the larger robots, as well as in the darker implications of the smaller ones, there is an underlying element of menace. But with Rath’s propensity for fun, using brightly colored components and whimsical allusions to nature or toys, these objects ultimately share elation and delight with the viewer.