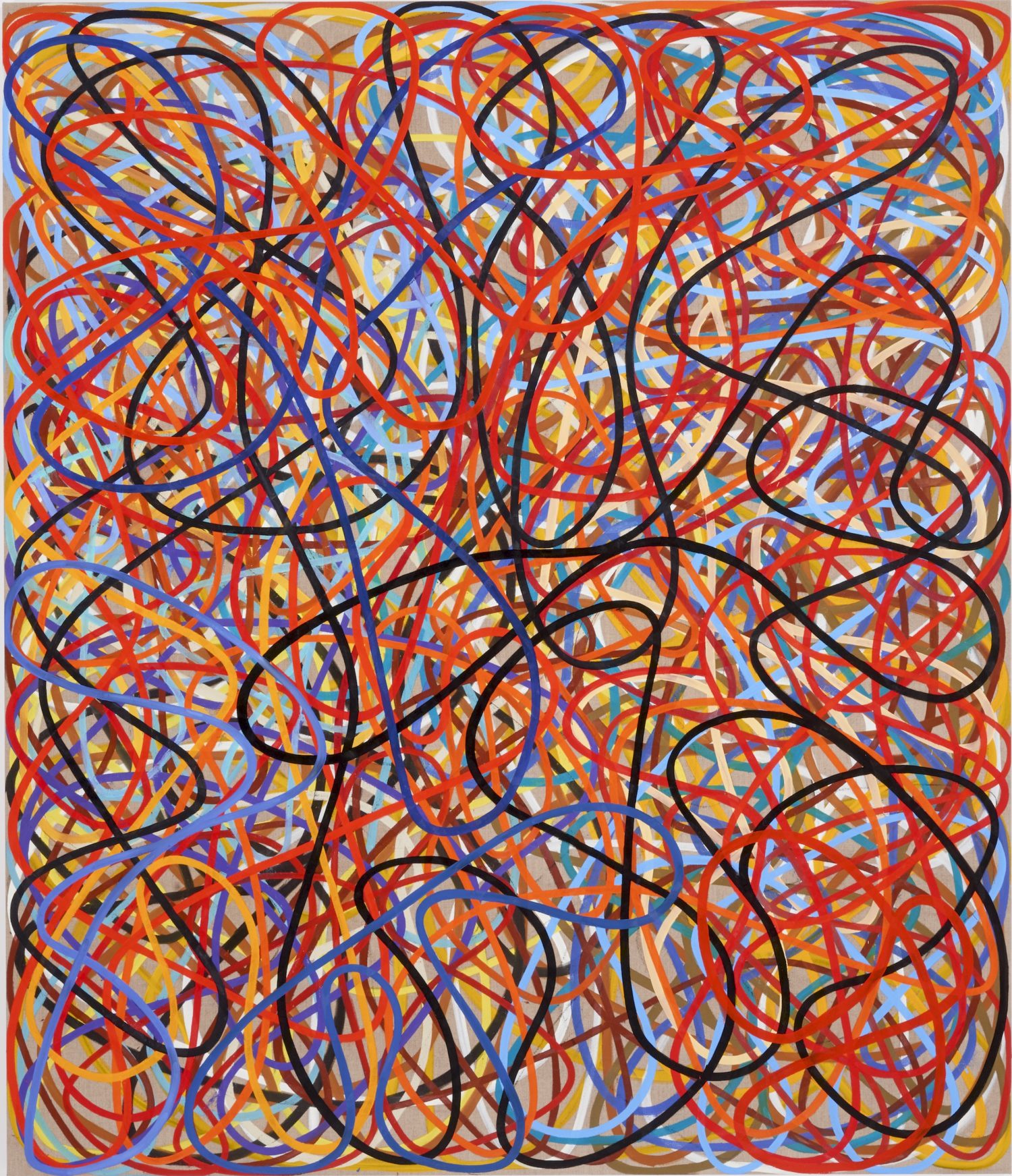

Inspiration must have been in short supply the day in 2012 that Sue Williams started Dallas, her painting featured at this year’s Frieze art fair. Like most artists, Williams undoubtedly set out to create something unique, a painting for the ages, as masterpieces are...