Perusing the 37 paintings by various Ghanaian artists in “Praise Portraits from Ghana: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly…!” feels like peering into an exotic parallel dimension of popular culture. At a glance, these depictions of mostly American actors, singers, models, politicians and criminals appear straightforward, even kitschy; but on closer examination, the stranger they seem. The familiar celebrity identities only accentuate the expressive singularity with which they were painted. With individual styles ranging from washy brushwork to detailed realism, the artists exude an evocative, though sometimes offbeat, sensitivity in bringing out their subjects’ characters. Their unconventional surfaces include wrinkled flour sacks and weathered boards, evincing resourcefulness and functionality. Each image is adorned by snippets of stylized text ranging from poetic phrases to advertorial declarations. Augmenting the intrigue, painters’ signatures include pert pseudonyms such as “Almighty God” and “Death is Wonder.”

Most of these artists began as sign painters in a vibrant Ghanaian tradition of hand-painted advertising that flourished in the 1980s–’90s when enterprising businessmen commissioned imaginative movie posters to promote mobile “video clubs” that traveled around Ghanaian villages screening movies on portable VCR’s. At its peak, call for the movie posters was so great that cottage industries of masters and apprentices developed around them; but by 1999, demand had all but disappeared due to technological changes, and artists needed to find new ways to earn their living.

Death is Wonder, Osama Osama, 2001. Courtesy of Ernie Wolfe Gallery

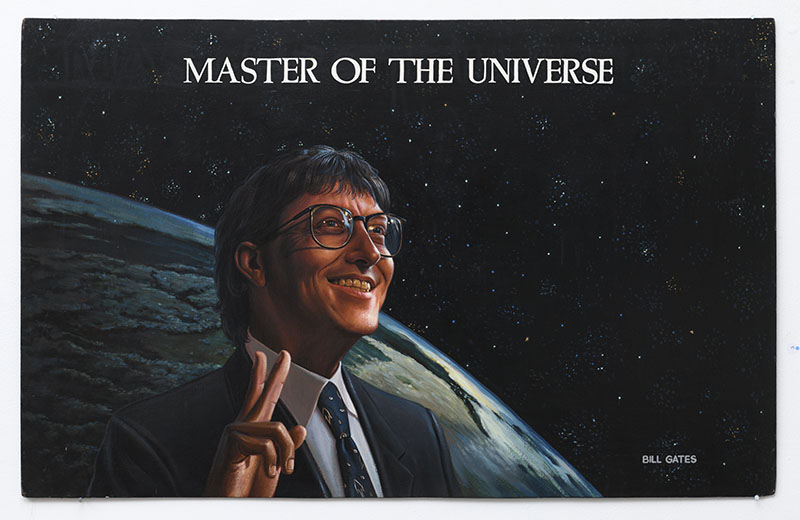

This show includes one hand-painted movie poster from the mid-’90s; the rest fall into a spin-off category of “praise portraits,” which gallerist Ernie Wolfe defines as “an indigenous Ghanaian art genre of single-image paintings of celebrities in advertising.” Whereas the movie posters centered on artists’ fanciful interpretations of fictional cinematic narratives, these Praise Portraits feature real people and world events as subjects of whimsy with a critical twist. Ghanaians are clearly fascinated by American culture; but the “praise” is often served with a dose of sardonic humor. Greed, power, prejudice and dissension are common themes. In a manner remarkably similar to contemporary Internet memes, Azey’s Master of the Universe Bill Gates (ca. late 1990s) features the titular billionaire as a slyly grinning demigod flashing the peace sign before a satellite depiction of Earth.

Whether contrived to sell local products or cater to the tastes of a foreign audience, these artworks are, in a manner, as commercial as American advertising. What sets them apart is the artists’ insistence on their own subjectivity. The handmade idiosyncrasy of their pictures is a refreshing contrast to the Photoshopped slickness that dominates our visual culture. Trademark-obsessed America tends to view cultural icons’ personae as incontestable. In selecting Western idols as subjects of burlesque, these artists hold an interrogative mirror to America’s deification of cookie-cutter mortals.

0 Comments