Before a few weeks ago, as far as I know, I had never had direct communication with anyone who’d even heard of The Rev. Dr. Fred Lane (though I’m sure some of the LAFMS folk could prove me wrong). Lane hasn’t released anything since 1986 when Shimmy Disc dropped his magnum opus Car Radio Jerome on an unsuspecting world. His only other LP—From the One that Cut You—was released three years earlier, on a DIY vanity label out of Alabama. But out of the blue, a mysterious stranger sent me an email alerting me to a recent flurry of activity by the reclusive artist.

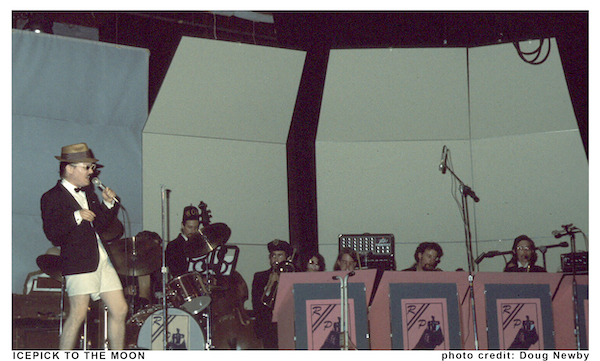

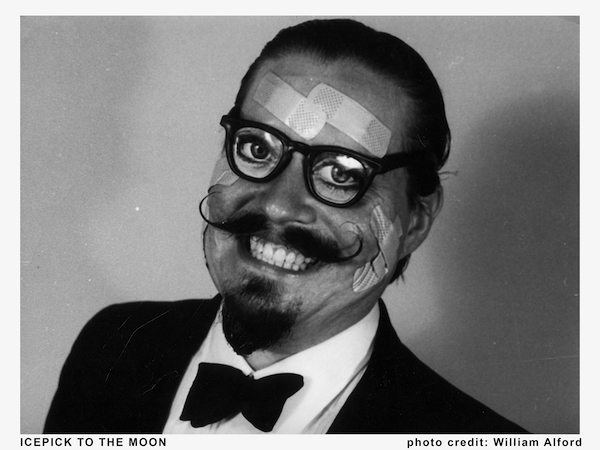

The dude is a mystery figure, supposedly the fictional alter ego of some Southern sculptor? He looks like something that got mashed up in a time machine—half beatnik, half Edwardian serial killer—losing his pants as he passed through the Summer of Love. His recordings are willfully outsider—in the same sparsely populated ballpark as The Residents, Half Japanese or Captain Beefheart. From a distance, you might think you were listening to some big-band spy-jazz combo fronted by a seasoned lounge crooner. But the closer you get, the normaler it ain’t.

Photo by Doug Newby.

The songs gradually reveal themselves as aggressively inventive and barely camouflaged experimentalism, starting out as country tearjerkers, kiddy’s ditties, bossa novas, spaghetti western or faux-Elvis movie songs — but veering suddenly into the skronk of free jazz or grind of industrial noise. But it’s the lyrics, delivered with an unctuous showbiz gloss, that immediately proclaim the artist’s profound idiosyncrasy. An example from his just released comeback:

Groovy student nurse all wrapped around the pizza boy

Shy little smile burnin’ down the Reichstag:

Cattle cars and singles bars is all the same to me

Noses into rectums throughout eternity

Little sinner…

The surface read of this whole package is comedic, but there’s something redemptively wrong with the humor. Lane comes across like a Martian with Asperger’s trying desperately—and failing—to assimilate, belting out show tunes through a circuit-bent universal translation module.

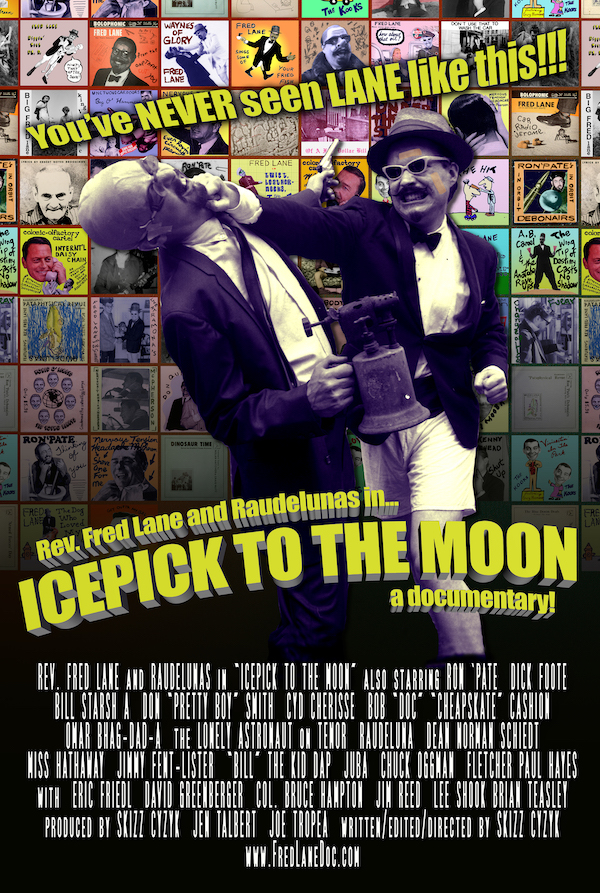

Lane’s new longplayer, Icepick to the Moon seems to pick up exactly where Jerome left off—which makes sense, since it was originally scheduled for release by Shimmy Disc in 1989, shortly before that worthy indie label crashed and burned. Now out from Feeding Tube Records (which seems to have something to do with Forced Exposure’s Byron Coley and Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon), Icepick is—if anything—more risqué than its decades-old predecessors.

Poster.

The Fred Lane persona hinges on a boozy, obnoxious mid-century toastmaster aesthetic, but the attendant racism, sexism and homophobia are so garbled by their ‘patacritical filtering that they leave nothing coherent to object to (not that objecting to the personality flaws in a fictional character is ever very helpful). Nevertheless the escalation of Lane’s “disturbing” quotient is palpable.

The details of the generation of the Lane entity are unraveled in a recent documentary, also entitled Icepick to the Moon. Cobbled together from 20 years of videotaped interviews, vintage Super 8 footage, fresh animation and performance documentation, Icepick—the Movie chronicles a micro-culture of stoner bohemian avant-gardism in ‘70s Tuscaloosa, inspired by Alfred Jarry and DADA and known as Raudelunas.

Photo by Janice Hathaway.

Occupying the same transitional historical pocket between late-hippy Freak culture and Punk as the LAFMS (among others), Raudelunas members (including CalArts Experimental Sound Practices professor Anne LeBaron) printed zines, mounted exhibitions, infiltrated homecoming parades, and staged absurdist variety shows—it was to MC one of these stage shows that The Rev. Dr. Fred Lane was first summoned.

Throughout Icepick—the Movie, interviewees consistently refer to Lane as a sort of Captain Howdy figure—a possessing spirit that manifested in full blossom in the host body of flautist/sculptor Tim Reed, then basically took over. Even Reed himself—who now makes eccentrically whimsical lawn whirligigs to sell at craft fairs—seems to be going along for the ride.

Even though it details how a cheap rent/tuition/drugs milieu can produce some riveting creative moments that ripple, lo, into the dystopian future, and deconstructs much of the mythologizing that had sprung up among Lane’s small but rabid following, there’s nothing in the film to explain away the almost shamanistic otherness lurking beneath the cheesy novelty facade — or the raggedly virtuosic musicality. The Mystery of Fred Lane lives on!

Thanks for the review. Fred deserves adulation and laughs.