Many artists, we’ve been told, are obsessed. The way they repeat a subject, or a theme, their attention to detail or to finish, or just the impressive volume of work they produce, can only be explained by obsession. They think about feet or toast or red a lot—maybe too much. It’s a diagnosis.

An artist can also be a voice. A brave voice, a new voice, a dissenting voice, a strident voice, a trailblazing voice. A voice says. Communicates a message, often quite literally and in a way professional interpreters of art translate into words.

You don’t much, in the art world, get an obsessive voice. The one called the obsessive and the one called the voice are usually different people, because they describe two different sets of assumptions about the artists’ relation to the concept of work.

The obsessive artist is almost always coded as privileged—white or wealthy or both—with a thousand other options, it’s implied, that they could’ve done with their lives and they’ve chosen dots, or little squares, or pictures of meat. Joseph Beuys, Fred Tomaselli—they’re obsessive. They are like Furries, or that German who wanted another guy to eat him, a case study in the extremes of human psychology. Curious.

Joseph Beuys, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare performance, 1965.

The voice is coded as marginalized—their work protests something, or, merely in being itself, implies the sensibilities associated with a marginalized identity. In contemporary art, the phrase “voices such as” is usually followed by a list of people who are queer, not white, or from countries outside NATO. Unlike those decadent obsessives, the voice has no choice. Simply in order to be understood at all, to be able to simply speak and have their messages understood, they must make art, put it in galleries, have this art seen, have it be decoded by art people.

What neither of these artists is coded as (despite being) is gainfully employed. That is, doing what everyone else is: taking up a role where they give something largely because the world is interested in getting it. What’s casually elided when discussing the obsessive or the voice is that these urgencies—whether allegedly psychological or allegedly sociopolitical—are called up by writers to explain the same reality: you might want to look at the art they made. “Obsessive” is a shorthand meant to explain that there is a lot here, and you might enjoy the a-lot-ness of it all, saying something is from a “voice” is a shorthand meant to explain that there are things being said that you might want (or need) to hear.

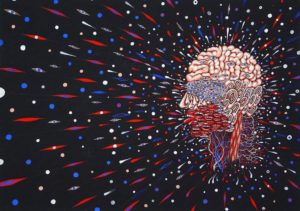

Fred Tomaselli, Untitled, 2003.

If your pizza is delivered in 30 minutes or less and your pizza driver works eight-hour days; full time for the usual 261 weekdays a year, he or she or they is/are delivering over 4,176 pizzas a year. That is so much pizza. Are they obsessed with pizza? Are they a voice that must deliver the message of pizza? No: it is you, the customer, who wants the pizza, and they are someone who has come to the understanding that constant contact with pizza, your tips and the traffic that intercedes between the birthplace of the former and the dispensation of the latter is their best option at this moment and in this world. Maybe they even like pizza.

“What dark drive compelled you to make the art this way?” “I wanted to look at it, and so do you or you wouldn’t be here at my slide show or asking me this question on my Instagram, and so one of us had to make it, and you didn’t. Plus I get paid.” Ascribing art to compulsion is like sitting on someone’s deck, enjoying a barbecue, paying them for the privilege, and then asking why they built it.

New Yorker cartoon.

There are time-honored advantages to the exegetical tic of the artist as uniquely driven: if we assume the artist has something beyond the utterly comprehensible desire for the art and the money it might bring, then they are a holy fool, free from the responsibilities and compromises that plague ordinary mortals. But these categories also limit the conversations we can have: instead of the artist being obsessive, we might discuss how audiences like colors and dots and the relatively rare visual phenomena made possible by eccentric hard work and ask why we are so starved of these things in this world we built, and instead of the artist being a voice they might get to be a person, who has an infinity inside them like anyone else and we might ask ourselves why we so desperately want them to keep telling us the same things even after we believe them and why we delegate this task to someone we visit in a glass-fronted closet from 11–5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday.

0 Comments