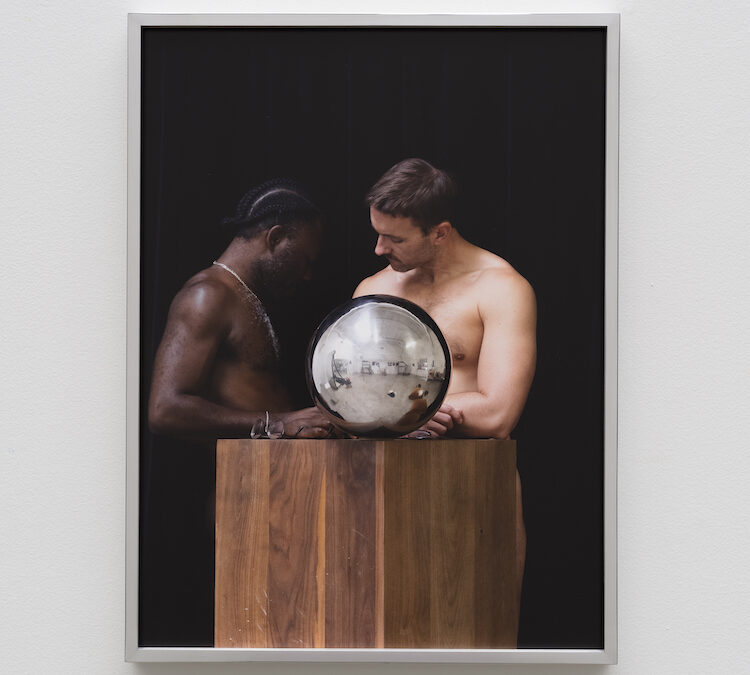

On the top floor of The Gaylord Apartments, a spare selection of seven new paintings by Magnus Peterson Horner tingles the optic and haptic senses, even when they’re barely paintings, even when they’re barely there at all. Horner paints people as if sensed through...