For the 9th edition of the Artes Mundi Prize, an international panel of jurors —made up of Cosmin Costinas (Executive Director and Curator of Para Site, Hong Kong), Elvira Dyangani Ose (Director at The Showroom, London) and Rachel Kent (Chief Curator at MCA, Sydney) — shortlisted six established and mid-career artists whose works expose the relationship between the individual and the collective, unfolding across memory and history. Whilst the final winner will be announced on April 15, a digital version of the exhibition has recently opened with a rich public program. An overt quest for healing and reconciliation among human beings, and within a culturally and emotionally displaced self, are at the center of Dominican Republic-born artist Firelei Báez’s research. Historic maps and diagrams from colonial periods support the artist’s colorful and detailed drawings which often depict the majestic bodies of mythological creatures, the Ciguapas. The three large-scale paintings realized by the artist for Artes Mundi 9 are caught in the act of “traversing” the plain surface of the map grids, printed onto the canvas, in search of situating unprivileged histories and geographies differently.

Firelei Báez, the soft afternoon air as you hold us all in a single death (To breathe full and Free: a dec-laration, a re-visioning, a correction), 2021 (detail). Acryl-gouache and chine collé on archival printed paper. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photography: Stuart Whipps.

While interconnections among locations and individuals are present in Firelei Báez’s works in the form of an emotional attachment to a far-away place, the Ghanaian artist Dineo Seshee Bopape explores the influence of a global history over other, local ones by emphasizing the metaphysical and spiritual dimensions of materiality in her immersive works. Across over 1000 drawings gathered together in unfinished grids as part of Master Harmoniser (2020), Bopape uses soil and clay from different locations across the U.S. and Africa that have been marked by the history of the Atlantic slave trade. The rest of the rooms dedicated to Bopape’s works have walls washed with soil from sacred Welsh sites. These spaces host the sound piece Gorree (song): Thobela: harmonic conversions (2020) and the remnants of (Nder brick) ___ in process (Harmonic Conversions) (2020), a spiritual ceremony she made in homage to Northern Senegalese women who sacrificed their lives in order to escape enslavement. The intimate personal belief systems that people to navigate history and, equally, to preserve memory from disappearing, are fundamentals to a deep understanding of the artist’s creative proposition.

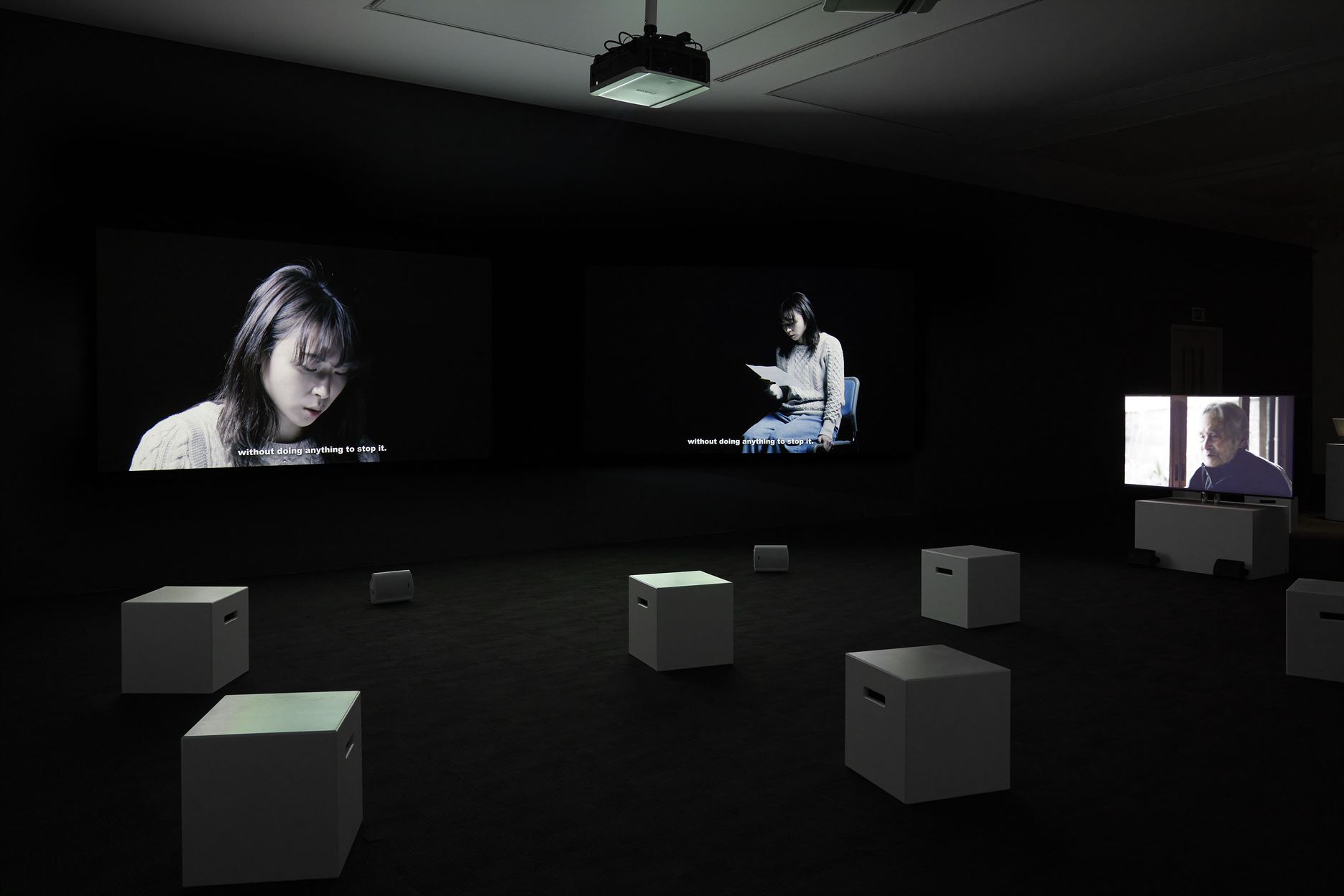

On the contrary, this private and introspective dimension seems to be denied and turned away by official accounts of history and memory investigated by Japanese artist Meiro Koizumi investigates in Angels of Testimony (2019). The work consists of three, screen video pieces where the artist prompts confrontations with his own national guilt, alongside younger generations of fellow citizens. Whether they are filmed in the rehearsal space of the artist’s studio or in crowded Japanese streets, public testimonies from an elderly veteran of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), provoke a cascade of conflicting sentiments within the exhibition space. An emotional fatigue and exhaustion is thus perceived as a side effect of a never-ending tension between forms of reappropriation, omitted national histories, self-reconciliation and collective healing. In Koizumi’s work, history and memory appear as malleable and deformable entities that evolve within the ongoing relationship established between human beings and their broader surrounding.

Meiro Koizumi, The Angels of Testimony, 2019 (detail). Three-channel video installation, colour, sound, archival materials. Commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation. Courtesy the artist, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam and MUJIN-To Production, Tokyo. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9 Photography: Stuart Whipps.

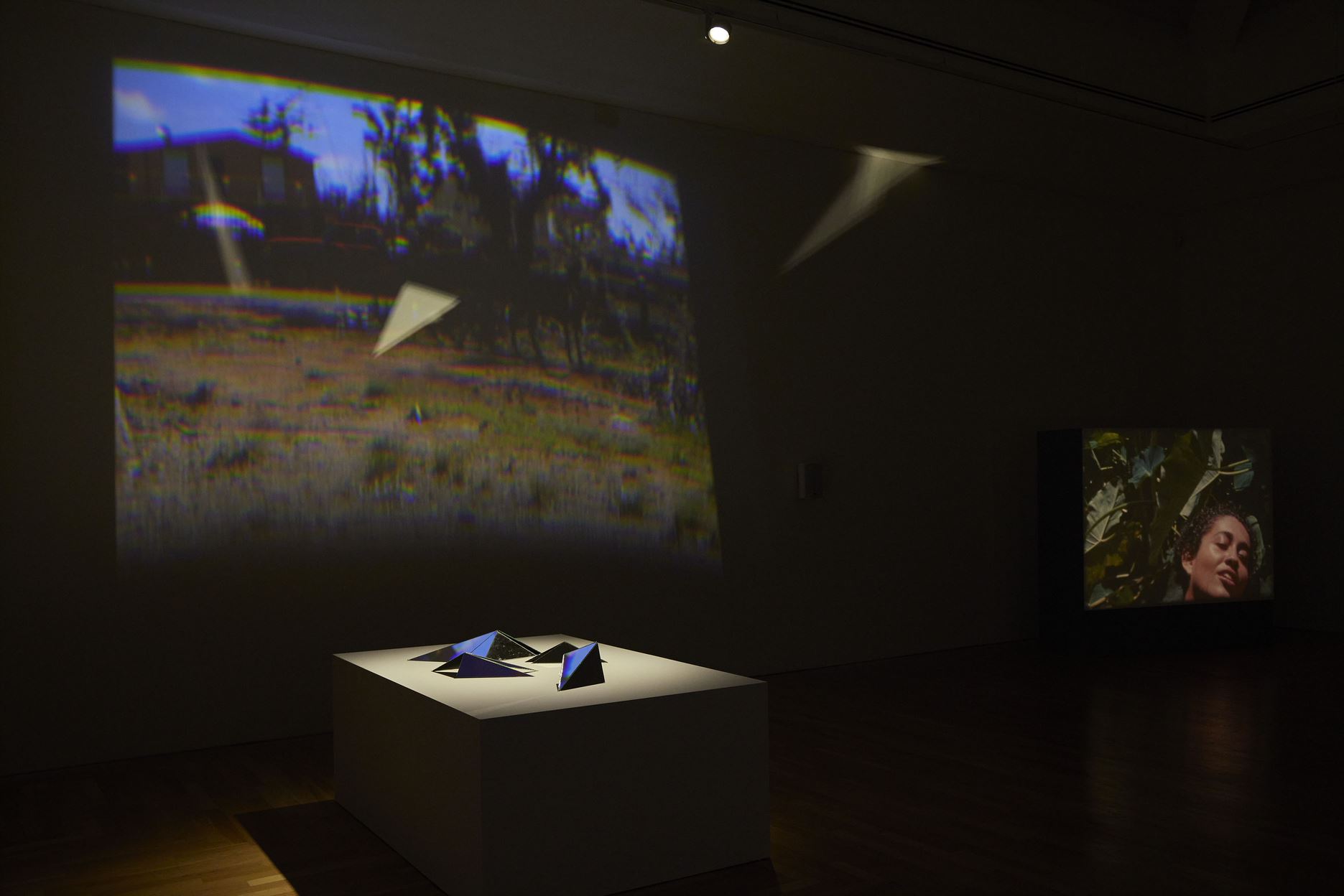

Through her film installations, Puerto Rican artist Beatriz Santiago Muñoz registers changes and deviances observed within the lives of local communities, by actively intervening on the viewers’ perceptions. The main sensorial faculty called into question is certainly sight. At the center of the room, a series of forms made from triangular pieces of mirrored glass titled Malascopios 1-5 (2020) —a Spanish neologism invented by the artist to indicate the act of “see wrong”— generate kaleidoscopic effects across the 16mm film projections. This is evident in Otros Usos (2014), a film shot on a former US naval base in Ceiba, Puerto Rico, where land, sea and sky collapse in an abstract succession of images.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Installation view: Artes Mundi 9. Courtesy the artist. Photography: Stuart Whipps.

Explorations of the landscape as a sort of memory-catcher of the countless spoliations—realized by humans and non-humans alike—on post-colonial states are further carried out by Indian artist Prabhakar Pachpute. Pachpute perpetrates a subtle disambiguation between reality and imagination through the restoration of dystopian and archetypal imaginaries. Drawing from his family history of three generations as workers at Indian coal mines, and deep archival research into the Welsh mining community, Pachpute’s large paintings portray landscapes where vegetation, humans and animals are the great, felt absent. In such desolation, however, a window of opportunities of a better world, encompassing cooperation and solidarity among workers, as well as between human and non-human entities, is left open through the symbolic use of the clenched fist. A march against the lie (IA) (2020), shows a clenched fist rising from a topography of soil on a draped canvas and sets the tone for engaging with American artist Carrie Mae Weems’s photographic works.

Prabhakar Pachpute. The march against the lie (1A), 2020. Acrylic and charcoal pencil on canvas. Courtesy the artist and Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9 Photography: Stuart Whipps.

Artes Mundi 9 seem to recognize that protests are, ultimately, the pivotal element which allows human and planetary history to take unexpected routes, often through processes of rupture and renovation. This strong affirmation should be contextualized in the way Weems’s multi-image works offer a commentary on hyper-contemporary transnational unions and cross-cultural collectivities. Presented when the larger global movement of Black Lives Matter began to take to the streets worldwide, The Push, The Call, The Scream, The Dream (2020) puts forward a clear gesture of solidarity toward those who fight for justice and equality for all. By highlighting the role that singular individuals play in the unfolding of history and in the fabrication of new memories, Weems’s work stresses also that these histories and memories cannot be fully understood alone. Instead, they require an analytic sight of the interconnections that characterize our humanity, capturing a broad span of experience, from moments of solitary mourning to the restoration of collective intimacies.

Carrie Mae Weems, Repeating the Obvious, 2019. 39 digital archival prints of various sizes. Courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9 Photography: Stuart Whipps.

Carrie Mae Weems, Repeating the Obvious, 2019. 39 digital archival prints of various sizes. Courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9 Photography: Stuart Whipps.

Artes Mundi 9

National Museum Cardiff, Chapter and g39

March 15 – September 5, 2021

Artists: Firelei Báez, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Meiro Koizumi, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Prabhakar Pachpute, Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems, Repeating the Obvious, 2019. 39 digital archival prints of various sizes. Courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9 Photography: Stuart Whipps.

Carrie Mae Weems, Repeating the Obvious, 2019. 39 digital archival prints of various sizes. Courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Installation view: Artes Mundi 9 Photography: Stuart Whipps.