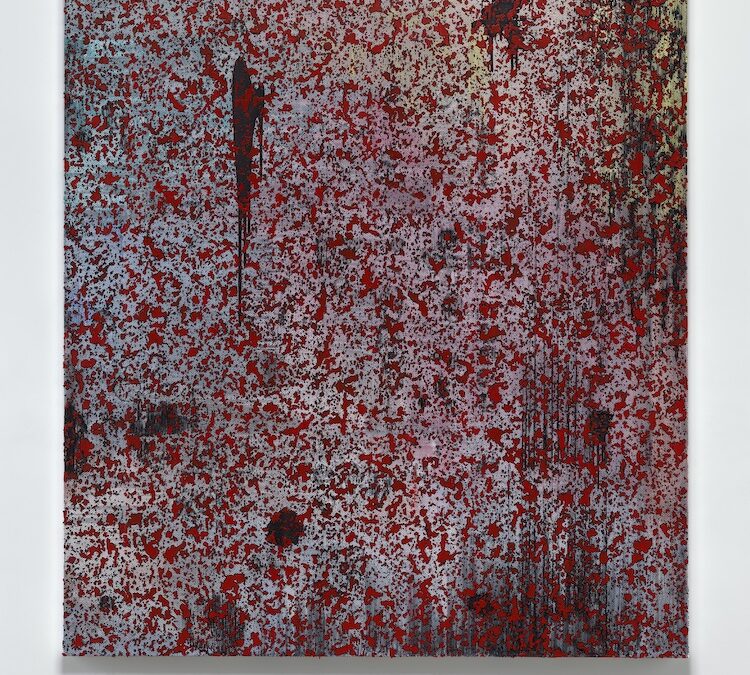

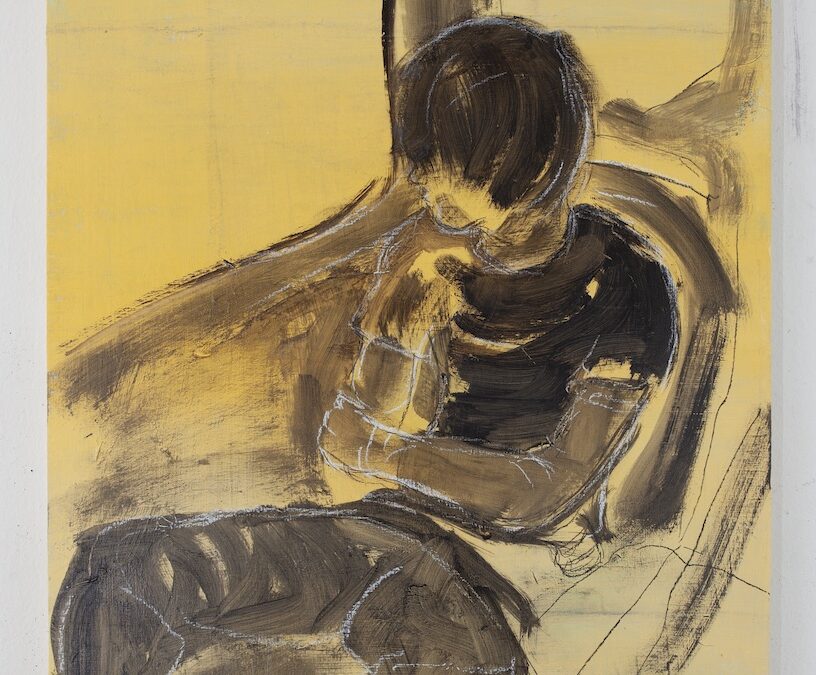

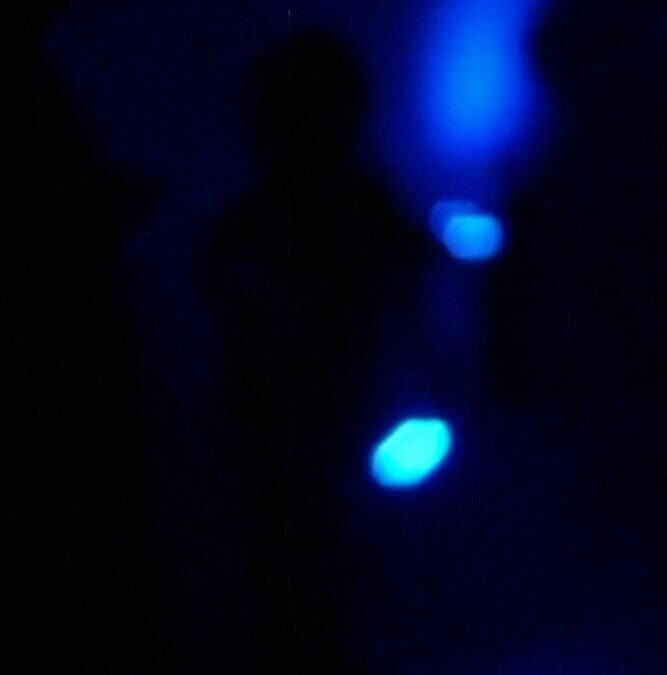

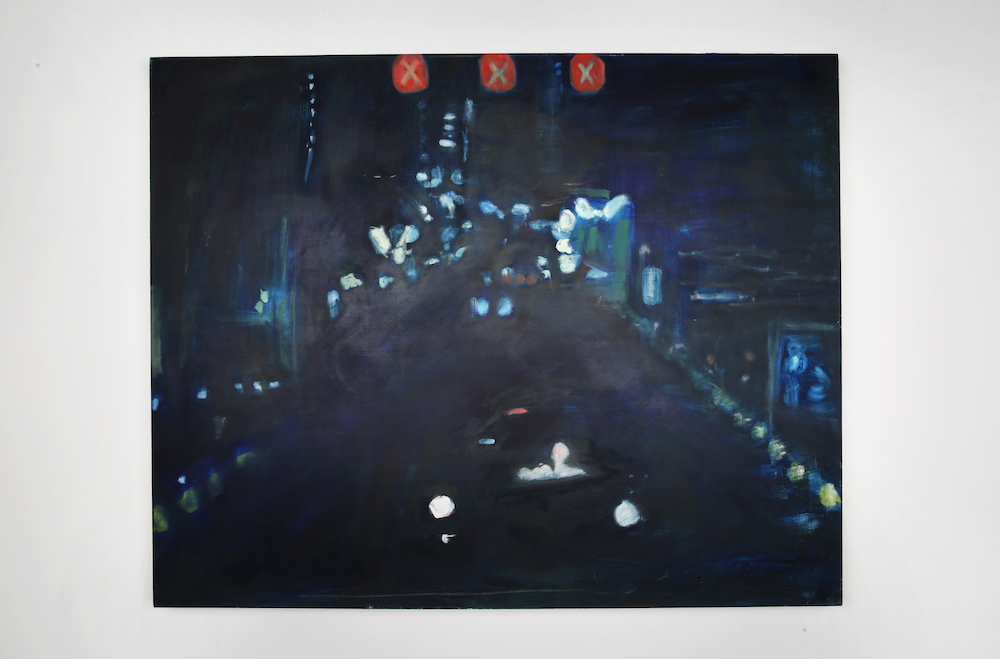

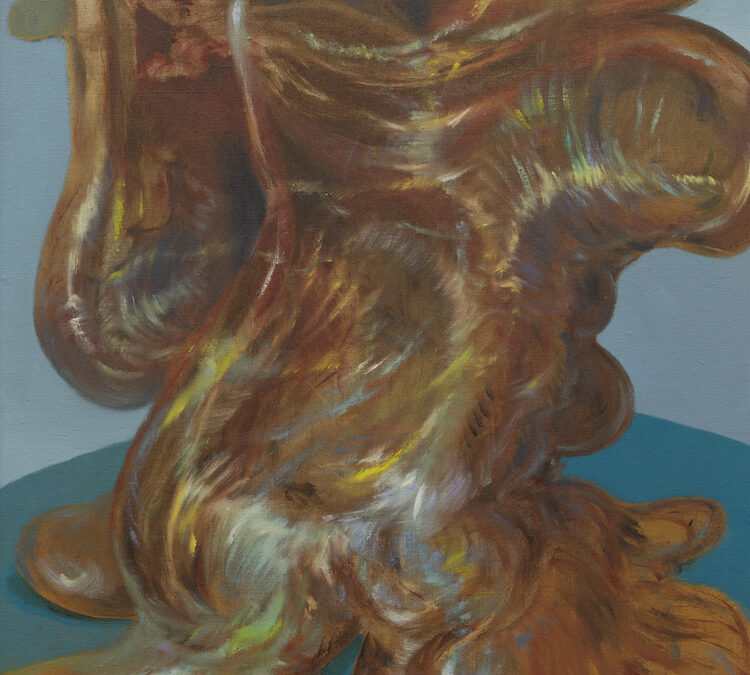

Two big rooms of Mary Weatherford’s prodigious wall works still aren’t enough space to contain the mesmerizing views the artist generously presents in “The Surrealist” exhibition, which is a bold, seductive reminder of painting’s emotional power and material...