Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: art review

-

MAGNUS PETERSON HORNER

at Gaylord Fine ArtsOn the top floor of The Gaylord Apartments, a spare selection of seven new paintings by Magnus Peterson Horner tingles the optic and haptic senses, even when they’re barely paintings, even when they’re barely there at all.

Horner paints people as if sensed through eyes hardly cleared of amniotic fluid: a vision that’s fuzzy and faint, but still so raw that we barely know what to do with it.

Portrait of a Young Boy and Head of a Young Boy (all works 2025) show broken perceptions, so decomposed that the impression of a personal presence takes several seconds to emerge. Each ekes out a minimum of differentiation between figure and ground, so that the surface and the painted skin do not really split, remaining interpermeated.

From there on, every surface looks like sensitive skin. Gazing at these surfaces leads to an uncomfortable vicarious feeling, a sense that we—the viewers—suffer from the same sensitive skin condition suggested by the paintings’ odd texture. Bust of a Woman bears a broken fragment of torso, the sense of exposure heightened by the texture of the figure, which the painter deforms with a puckering or blistering technique. Other likenesses are smeared with photo developer, a chemical foreign to the medium. It curdles the paint and quite literally makes the represented skin crawl, impeding the viewer’s reading of the limited tracings that emerge.

Installation view, Magnus Peterson Horner, 2025. Courtesy of Gaylord Fine Arts. Even more friction comes from the angle of representation itself: if this is portraiture, it’s rethought from such a distant starting point that a first walk through the exhibition might permit little more than a marvel at the scattered strangeness of the artist’s imagination. One untitled painting consists of only a mesh cloth stretched on a wooden armature. In another, around the corner, Kraft singles set behind picture glass create an imperfect checkerboard pattern. It’s unclear whether Horner foresaw how the cheese would mold or planned the squares’ decomposition, which is proceeding in an orderly right-to-left direction.

And yet ghosts of association among these incompatible objects somehow float back in. These affinities are not so much narrative as primitively sensory, charged with reflexes rather than stories: the mold recast as a complexion’s floral outbreak, the mesh charged with an aura of cheesecloth wringing liquid from a lump of organic matter. The grid of threads hints at a kind of straining but doesn’t perform it, making present just the sensitivity, the foretaste of sensation.

While staring into the checkerboard’s edge, fraying greenish, I thought of Harmony Korine’s 1997 movie Gummo. Why? Horner’s paintings don’t shock; nothing resembles the explicit abuse and cat killing for which Gummo is notorious. Perhaps the framed cheese reminded me of a stray detail from the movie: a strip of bacon taped to bathroom tile behind the boy-narrator, Solomon, as he eats dinner in the tub. But I don’t think the connection is superficial. Horner’s persistent subject, oftentimes just glimpsed through fits and starts, is the same excruciating exposure of childhood that Korine’s film pushed to an extreme.

Portrait of a Young Boy, 2025. To be clear, it’s Solomon, not Korine, that Horner resembles. His paintings evidence a certain distinctive imagination, unpredictable and frank, which resonates as a generational sensibility. In a past exhibition at the Queens gallery Gandt, for example, Horner showed a painting of a still from a game of Fortnite played by a boy he babysat. But the impression of the virtual world was so defamiliarized that it could only have been found by eyes completely foreign to the game, or ones so glued to it that any ordinary familiarity had melted away.

If it’s true that Horner’s mind was embedded formatively in a deep matrix of media, in these new paintings he seems to have come out the other side. Nothing digital is present, except perhaps as a sort of afterburn that washes out a painting like Head of a Young Boy, which might show how a sunlit face appears to immoderately online eyes. Horner paints not the liquid crystal screen, but the effect that it produces. The viewing angle of Girl with a Kitten, stuck at an odd angle of fixation, could similarly be read as an aftereffect of POV inundation, but only if you go out on a limb. These symptoms aren’t specific to any technology in particular. The congenitally fuzzy gaze they bespeak feels more general, or even, again, generational.

This persistent sense of disorientation is a strength, and it’s heightened by a confident restraint in curation. I was told by the Gaylord gallerists that a good chunk of the works Horner brought from New York were, upon deliberation, tucked out of sight. I’d have loved to see them, but their absence only adds to the square-one charge. The same goes for the press release: there wasn’t one. Rigorous subtraction fuels the fantasy of new eyes, or newly perceptive ones, concentrating focus on the acute sensation of what survives the paring-down. Here, realized in sparse gestures, it’s a world almost painfully lush.

-

Sandra Cinto

The delicate line-work in these semi-abstract sea/land/sky-scapes is incredibly controlled, almost to a fault. It doesn’t leave much room for the unexpected. This might be okay except that the overall vocabulary of forms is a bit too constrained. For instance, the squiggly undulating seas, asterisk-like stars, and meandering triangular lattice-works all start to feel schematic—like well-practiced versions of familiar forms. The glitzy gold backgrounds and matte neutral tones split the difference between tasteful and ostentatious, but do not land anywhere particularly original.

Sandra Cinto: Prelude to the Sun

Tanya Bonakdar

1010 N. Highland Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90038

On view through July 2, 2025 -

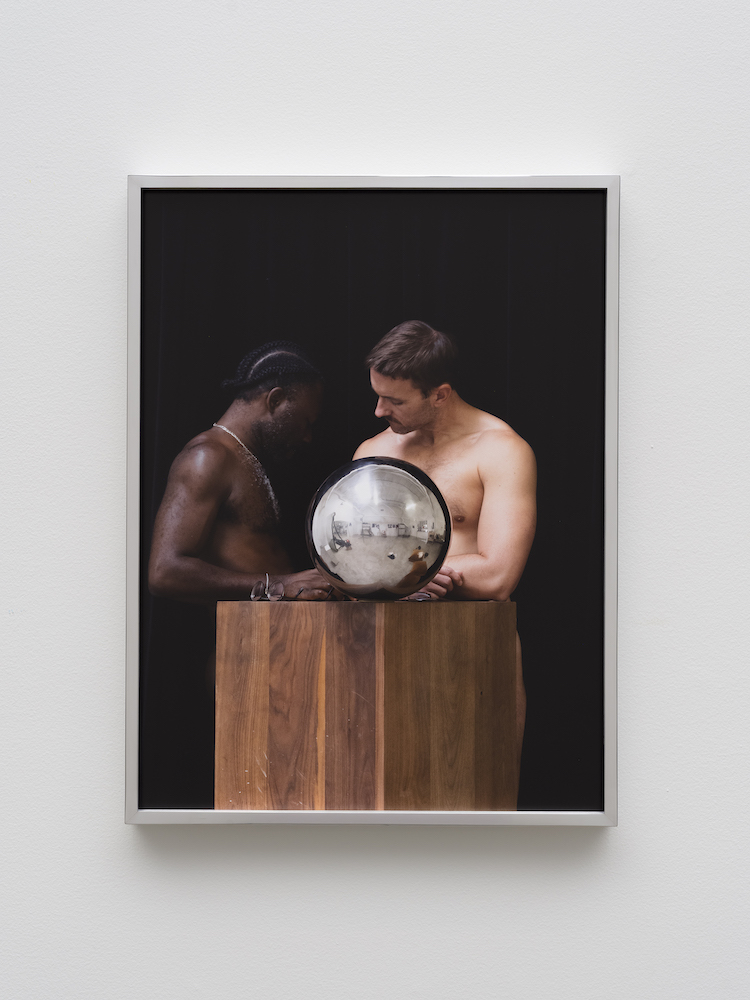

Paul Mpagi Sepuya

at VielmetterThe title “positioner” refers to the photographer’s inclusion of himself in several of these photos as he positions his models, most of which are queer men and women. These are a reflection on studio portraiture as a specific social context. They explore the relationship of photographer to model, not just on an interpersonal level, but as it reverberates within the context of the studio and the artist’s practice. The content is not intimacy, per se, but the care, communication, and technique that go into capturing it. These are continually rewarding on conceptual, formal, and psychological levels, which reveal how all of the above are also intertwined.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: POSITIONER

Vielmetter Los Angeles

1700 S. Santa Fe Ave., #101

Los Angeles, CA 90021

On view through July 19, 2025 -

Jill Magid

at Various Small FiresThe centerpiece of this show is a carpeted wooden platform, covered with white on blue stars like an American flag. Various Small Fires’ owner, Esther Kim Varet, is running for Congress, and this mini-stage is meant for use by her campaign. What Varet and artist Jill Magid offer is a call to action—something which most political art fatally lacks. This is a welcome corrective to art that thinks making a political statement counts as doing politics. There are also twenty heart sculptures, cast in grey cement, in the atrium, suggesting the heart it takes to get involved. A third piece, which includes the official forms for declaring oneself as a congressional candidate, underscores this point. 50/50 stars.

Jill Magid: Heart of a Citizen

Various Small Fires

812 N. Highland Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90038

On view through June 28, 2025 -

Mary Weatherford

at David Kordansky GalleryTwo big rooms of Mary Weatherford’s prodigious wall works still aren’t enough space to contain the mesmerizing views the artist generously presents in “The Surrealist” exhibition, which is a bold, seductive reminder of painting’s emotional power and material possibilities. Neon tubes, starfish, and coral press against luminous, amorphous, and almost galactic color fields in works that range from the intimate to the monumental. The artist’s deep commitment to pigment gives the surfaces a glowing, almost bodily presence. Her best paintings here—typically the largest—are both dreamy and visceral, undulating between clarity and mystery without fail. The show feels like an artist in full command of her language, unfolding history, memory, and matter into art that is formally elegant, unapologetically personal, and very much alive.

Mary Weatherford: The Surrealist

David Kordansky Gallery

5130 W. Edgewood Pl.,

Los Angeles, CA 90019

On view through June 28th, 2025 -

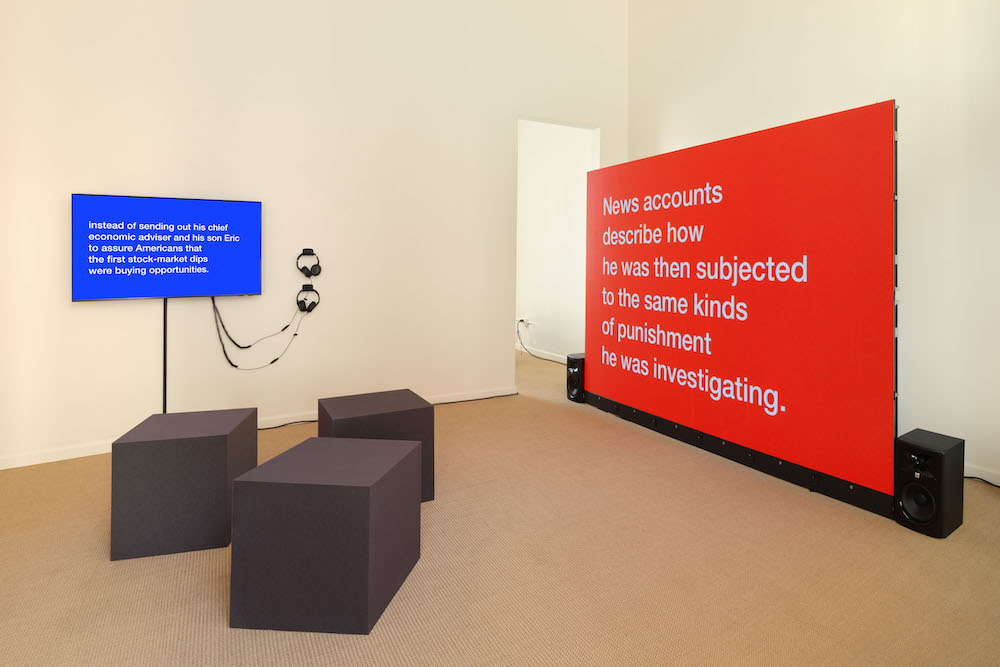

Tony Cokes

at Hannah HoffmanTo get to Tony Cokes’ “All About Evil” at Hannah Hoffman, a show displaying 12 selected works from a period of nearly two decades (2006-2022), one must pass a sidewalk sign for the neighboring jewelry boutique Spinelli Kilcollin. Cokes’ HD videos feature large white Sans Serif text against bright, embarrassingly and overwhelmingly American colors: red, white, and blue. Performing a patriotic zeal gone awry, the works pull the viewer in multiple directions at once: Device 1, a window flat screen, faces into the private, gated, courtyard, (where one must be buzzed in to view the work); Device 2, a wall-mounted flat screen, features two headsets for a pair of viewers to place over their ears, while a different song plays aloud from Device 3, an LED screen placed to the right of the small gallery space. The conditions surrounding this viewing experience are at odds with the overtly political content of Cokes’ work, which uses, for instance, the Sesame Street theme song alongside text on the response to coronavirus and the larger failures of the American political and educational systems. Stark text both confronts and entertains the viewer, who is offered a chance to sit on one of three large foam square blocks in the center of the gallery. Cokes’ provocative work reproduces a space not unlike an electronics superstore. The show offers neither space for immersion in a single work nor a path to political resistance. Instead, its success lies in the suggestion that rebellion itself has become a commodity, presented on multiple flashing screens with two soundtracks playing at once. The viewer is divided from themself, much like the user of an iPhone or Instagram.

-

MEGHANN STEPHENSON

at Half GalleryDario Argento’s 1977 film Suspiria left a lasting impression on me. It’s moments of indiscernibility, of looming disquiet, of eyes flashing against a blackened screen have stuck with me long since first watch. It’s an exhilarating study of the ominous, of unease, of femininity, and the complexities between, all of which are at the heart of Meghann Stephenson’s show “I’ll Be Your Mirror.” The seven oil paintings in the show are done in flat, muted neutrals and center around a woman set against a deep black background. Devoid of detail, the vacant backgrounds enable us to build a scene around the character and create our own fantastical stories from the moments Stephenson reveals.

In A Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing, the woman (who bears a resemblance to Stephenson) is slightly reclined, wrapped in a brown fur pulled tight against her throat, her hair tucked under the collar so not a glimpse of flesh is seen. Eyes squinting off to the left, she appears guarded against a looming threat. The quiet unease, the feeling of impending menace, isn’t limited to the external but emanates from the central figure herself. Her gaze, while wary, is unwavering as if tempting conflict. In I’ll Be Your Mirror, she and her she and her doppelganger, dressed in matching pink nightgowns, stare down the viewer with unwavering gazes that tease of unrevealed secrets. Behind them is a mirror in which one of them is reflected, back to us as if to defy scrutiny or legibility.

The work’s pared-down details can be understood as an omission; the figure reflective of a carefully crafted persona that threatens to break at any moment. Stephenson succeeds in illustrating the haunting experience of living within a fractured self.

Meghann Stephenson: I’ll Be Your Mirror

Half Gallery

By appointment only -

SELINE BURN

at Baert Gallery“Kairos” by Seline Burn at Baert Gallery features 10 large oil paintings on canvas and linen, all completed this year. Blues, yellows, and greens render female figures across landscapes and interior settings that blur the boundaries between inner and outer, self and other, human and avian, dream state and waking life. In North Star, a reclining woman’s breath takes the shape of a bird; in Ariadne’s Thread (2025), three nude women with feathered skin walk across a log bridge, connected by a rope suspended in their hands. In the smaller room of the two-room gallery, two complementary paintings would seem to drive us out of the mythical dreamscape into the reality of nature, with its consuming people and animals (a cat traps a bird, a large pretzel bears bite marks). My favorite piece in this show is Intertwined, which depicts two women, or two images of the same woman, lying beside one another, separated by a striped straw hat and by the fact that one wears a striped blue shirt while the other rests bare-chested. Lying in mirrored poses, their identical brown hair flows into one another as if shared strands. There is a decided absence of male figures in these paintings, unless Gargoyles and knives suffice.

Seline Burn: Kairos

Baert Gallery

1923 S. Santa Fe Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90021

On view through June 7, 2025 -

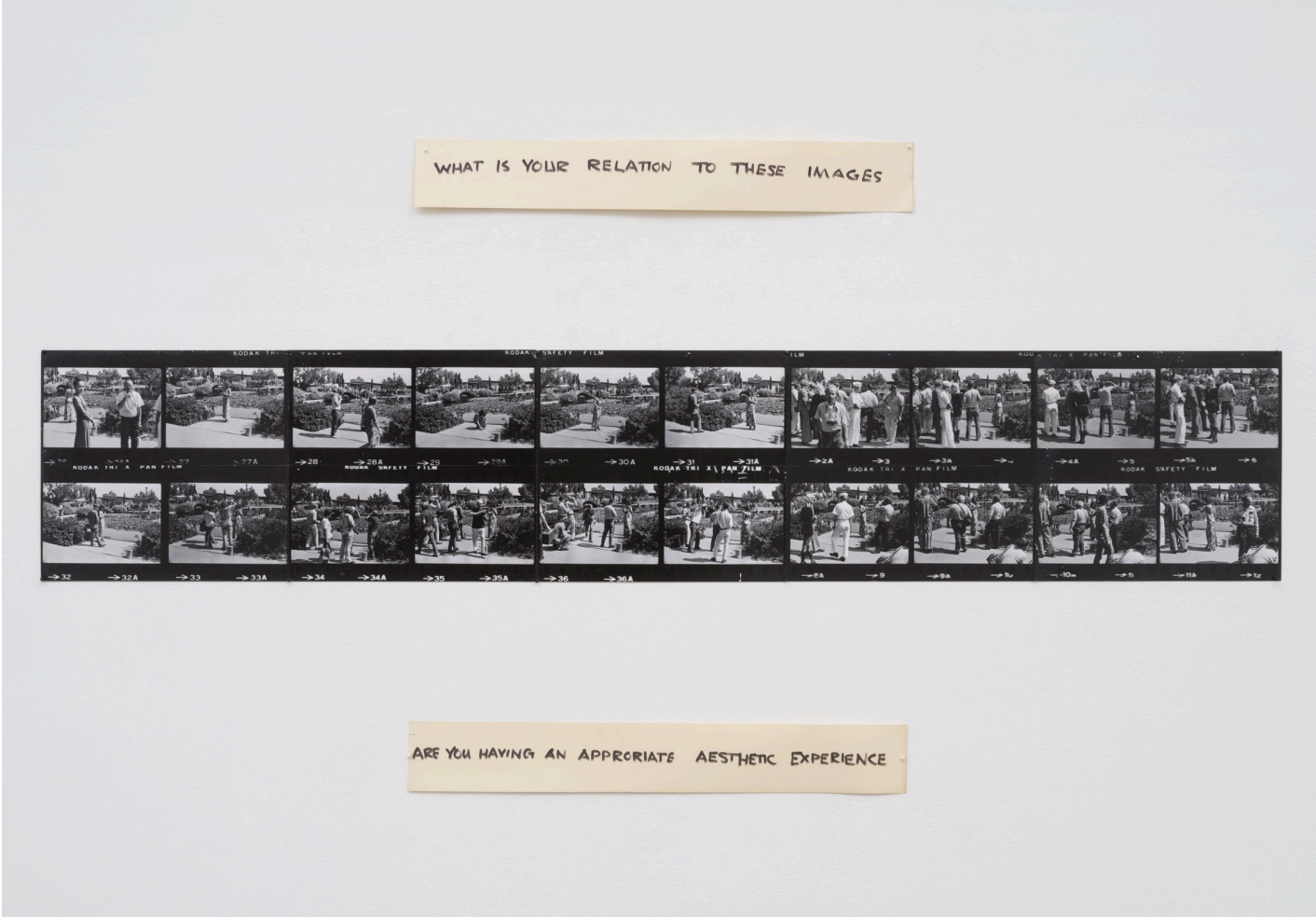

FRED LONIDIER

at Michael BeneventoWhen I look at Fred Lonidier’s show “Vacation Village Trade Show,” at Michael Benevento, my mind naturally goes to Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966). Much like Antonioni, whose film is about a photographer who inadvertently captures a murder, Lonidier is interested in the camera, and by extension the photographer, as a knowing entity, both a clarifier and obscurer of reality.

In “Vacation Village Trade Show,” Lonidier presents a sparse display of film strips paired with text. Scrawled on beige paper that sandwiches the images, the text above reads “What is your relation to these images,” while the one below asks “Are you having an appropriate aesthetic experience?” The trade show in question was an event in 1972 at a public garden in San Diego, where an entrance fee allowed amateur photographers access to models. Lonidier’s photos range from relatively banal and serene scenes of photographers in motion, examining their cameras, and milling around the park, to stark and nefarious shots of hordes of male photographers pointing their cameras at a bikini-clad model who poses and contorts on the grass.

An ardent leftist, Lonidier got his start documenting anti-Vietnam War protests, and the camera for him has always been a mirror, or perhaps a weapon. Less in the journalistic sense of documentation and more as a means of shielding from and bouncing back the elusive energy that is power relations. His work became trickier (a satisfying knotting) as he added layers of visual remove while maintaining his pointed political analysis. Expanding beyond the photographic image, Lonidier began to use text and performance-based gestures and staged shows in specific locales outside of a gallery context, all the while continuing to document the process. The images and text in his oeuvre, as well as “Vacation Village Trade Show,” depict a meta-photographic narrative. Lonidier is bumping lenses with his subjects.

In the Benevento office, advertisements for Vivitar lenses line the walls. Lonidier has circled, in red, key phrases on the lenses’ magical powers to seduce. The red circles, paired with newspaper and magazine clippings, suggest a conspiratorial web or a journalist on the trail of evidence (are the two that different?). The tucked-away office is also where Lonidier displays photos from the trade show where he has circled cameras and branded merch from GAF, a camera manufacturer (Lonidier has also made work about GAF’s labor practices). Like in Blow Up, the printed photo becomes evidence for a crime. Instead of merely exposing the oppressive gaze of the camera lens, Lonidier traces a line between it as a commodity sold through the sexualization of women and the preternatural power it possesses to frame, cut off, or linger.

Fred Lonidier: Valley Village Trade Show

Michael Benevento

3712 Beverly Blvd.,

Los Angeles, CA 90004

On view through May 17, 2025 -

Helmut Lang’s Burdensome Bodies

The R.M. Schindler House is unexpectedly quiet. Despite being smack-dab in the middle of West Hollywood, there’s a noticeable lack of noise around the house and grounds, as if the air is somehow thick enough to deaden dog barks and car horns. The silence somehow feels borne of the house rather than its surroundings. As one of three Los Angeles headquarters for the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, the Schindler House—the namesake of architect Rudolph Schindler—feels like a break in time. A leader of Southern California Architectural Modernism, Schindler’s 1922 home is the prototype for the aesthetic that placed a high value on unusual material pairings and the dissolution of boundaries demarcating inside and outside. In the hanging silence, the smell of old wood and ripening plants easily transports you back one hundred years, but with the resurgence of mid-century architecture, the site remains tethered to the present, too. It’s the ideal site for the free-standing sculptures and wall works of Schindler’s contemporary Austrian peer, Helmut Lang.

The photos of the works in Lang’s show “What remains behind” don’t do them justice. One must see them in person. On-screen or on paper, the sculptures appear (rather unsurprisingly) stoic and imposing—cold and indifferent, even. Made of foam, shellac, latex, resin, and steel, they contrast with the house’s cement floor and wood beams, appearing somehow darker. Curator Neville Wakefield scattered the sculptures across low-slung rooms, and in the photos, the works appear to domineer the space, suggesting an impenetrable tightness within an otherwise open architecture.

But the sculptures shone bright amber when I visited in the midday sun of a Sunday in February. The six tallest works, all part of the Fist series (works in series 2015–2017), are spindly stalks with bulbous growths atop them resembling crude femurs or, as the title implies, closed hands punching through the air to the low-hung ceilings. Their latex skins gleamed as if sweating, and I half expected them to begin dripping onto the floor. The natural light cutting into the house bounced off their curves and crannies, giving their twisted forms a vitality as if muscles caught in the act of contortion, capable of twitching and rearranging at any moment. Though brighter and smaller in person—the tallest of them almost rising to meet me head-on—they retained that imposing quality, exuding a pressing unease.

The two wall pieces felt more conventional, rectangular, and neatly enclosed in steel frames. Titled kleine Portrait Arbeit I and kleine Portrait Arbeit II, respectively (the loose translation of which is “small portrait work”), the plastic, wax, and shellac pieces resemble scabs ripped from a wound, slapped onto the wall, and framed. Repulsed though I should have been, all I wanted was for my fellow visitors to clear out so I could run my hand along their uneven skins.

Helmut Lang, kleine Portrait Arbeit I, 2015–17. Courtesy of the artist and MAK Center for Art and Architecture. In a later email interview with Lang, he asked, “Is sculpture not a form of body by definition?” The answer is, of course, yes, though I’d argue to various degrees. Auguste Rodin’s The Age of Bronze (1875) is a body, and Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981) is a body, but is Lang’s? These are bodies. Fractured, skinned, expelled. Those fists could be my fists; that skin could be my skin. Perhaps that’s why I find them so enticingly destabilizing: their familiarity, their proximity to my physical self. The collection is decidedly uncanny, for what is the uncanny if not the familiar made strange?

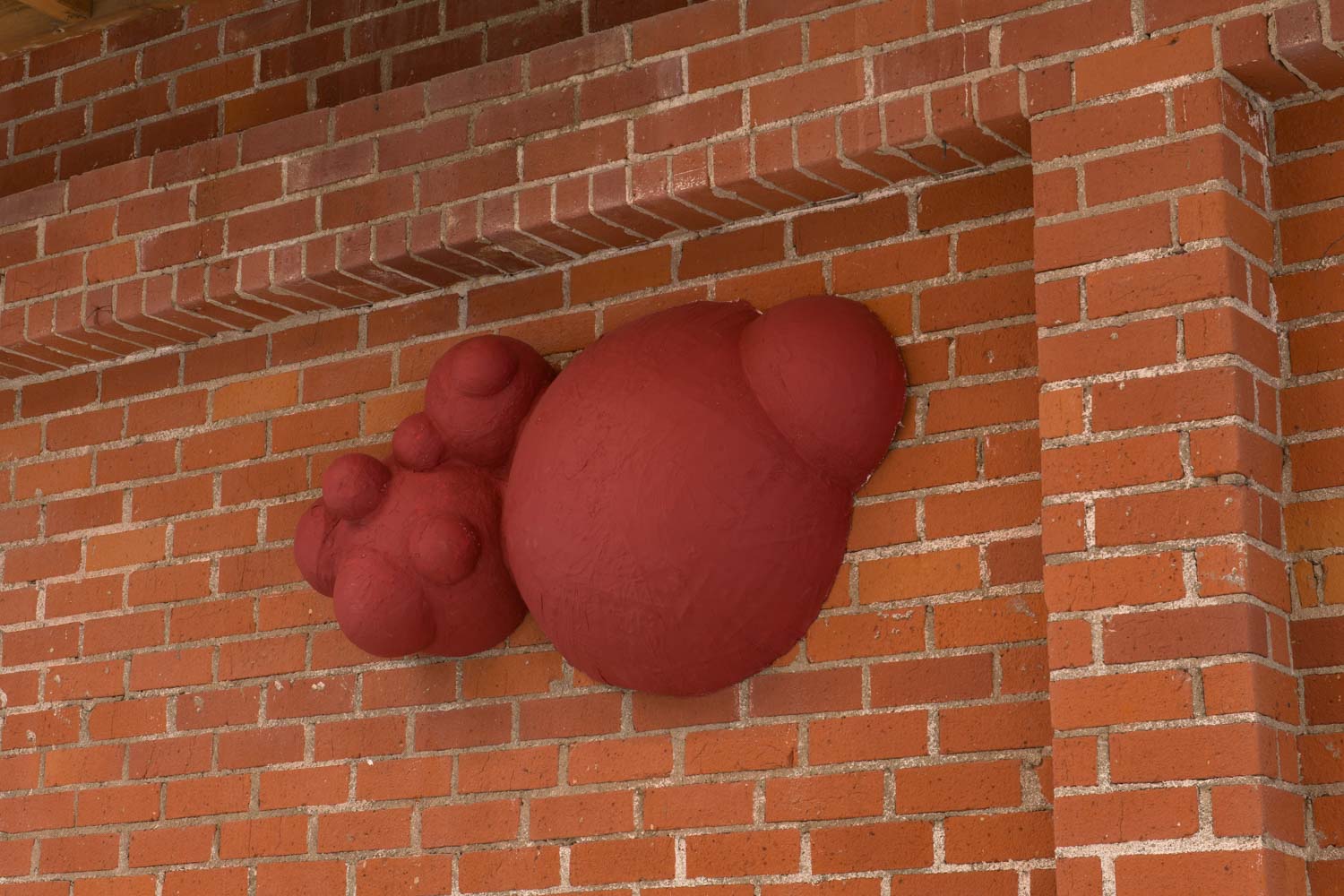

The uncanny, though, cannot be separated from trauma, a current that underlies much of Lang’s work. “At some point, human instinct overrides traumatic events and focuses on survival—not what has happened, but how to deal with it going forward,” wrote Lang in our correspondence. “It is a long journey that leaves the security of experience to create new realities.” To override trauma requires expelling oneself from certain comfort to the liminal space of frightening indefinability. It’s a violent act made visible in the two smaller sculptures, Prolapse I

and Prolapse II (each 2024). Reaching no more than three feet, they resemble rocks or, more fittingly, something you might dig out of your ear after a long time without cleaning. Unlike those in the Fist series, these pieces don’t have that iridescent sheen encasing them, which permits you to notice the texture more thoroughly, picking up on the bubbles and gaps left in their shellac coats. Like Schindler, whose architectural ethos put great emphasis on melding together the inside and outside, Lang’s Prolapse series toys with the edges of the human body and those fragile boundaries that demarcate our in and our out. The most visceral in name, the two works are manifestations of the liminal space that is “the body” and “of the body.” Left on the ground, they sit as the literal detritus of what’s been expelled, remainders of a whole that’s since moved on.

Helmut Lang, prolapse I, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and MAK Center for Art and Architecture. Underlying the show is a concern with history, specifically its burden. Therefore, it seems fitting for the show to be situated in the Schindler House, a space rife with temporal significance. The objective of preserving the home is to retain a spirit of the past in the present and to provide a jumping-off point for a yet-to-be-constructed future. For Lang, “The accumulated past, consciously or unconsciously, forms the physical, emotional, and intellectual material one is today. That is the starting point for all we do going forward.” Materially, Lang often uses the discards of former projects and scraps of handed-down objects that hold a history in and of themselves. He confronts these materials without sentimentality, tackling the malleable bits of collected waste until they become his hardened fists, skins, and prolapses.

The convergence of his own unrevealed history with that of the material undoubtedly contributed to the tension I experienced while walking through the exhibition. Lang’s abject objects are the broken bodies of multiple histories made manifest. The unspoken stories embedded in the works cut through the thick silence of the house and hang in the air as ghostly presences.

-

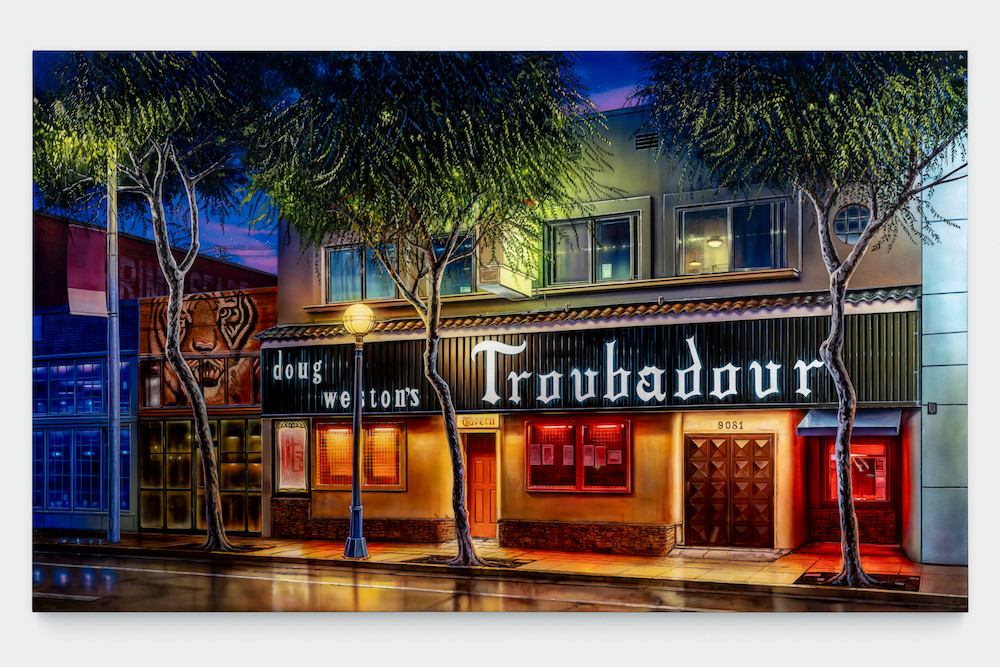

Alex Israel

at GagosianTo prepare for his current show “Noir” at Gagosian, Alex Israel claims to have walked about fifteen thousand steps per day around Los Angeles. This is highly unusual and, honestly, suspect. As the saying goes, no one walks in LA. Yet Israel insists on it and says that all this walking clued him into the more subtle, textured aspects of the city —things “[he] wouldn’t ever clock from the car window”—which ultimately informed his paintings.

In an attempt to better understand Israel and his work, I, too, began taking seven-mile walks around the city, daily: Van Nuys to Canoga Park, Glendale to Alhambra. El Prado to Sunset Tower. And so on and so on. I did my best to see the city as I imagined Israel would. I got into character—Alex Israel, wunderkind artist—and adopted that carefree, near-smug affect I’d seen in all of his portraits online. I did things that I thought he would do: I wore Ray Bans, smiled at nothing in particular, and listened to songs from mid-2000s iPod commercials. Slowly but surely, I started to feel cool and unhurried, the star of my own private sequel to Nic Refn’s neo-noir Drive: Walk.

Such a confident approach gave me clarity, and I realized that Israel was right. After seven miles of walking per day, you do start to notice the city’s hidden textures. Most obviously: for all their disuse (or perhaps because of it), the sidewalks are remarkably perilous, so full of fissures and crags that even a brief daydream comes at the cost of an ankle.

Alex Israel, “Noir,” installation view, 2025. Photo: Charles White. Courtesy of Gagosian. LA’s terrain, it turns out, is not easy. So, I’m surprised when I finally arrive at Israel’s “Noir” in Beverly Hills (by way of the Sherman Oaks Galleria, a four-hour walk through Benedict Canyon) to find a suite of paintings illustrating the exact opposite.

Apparently, Israel’s LA is easy. His paintings depict LA landmarks, both well and lesser-known—Chateau Marmont and the Troubadour, but also Trashy Lingerie and Hollywood Liquor—so completely awash in golden-hour purples and pinks that they’d fit neatly into one of Damien Chazelle’s La La Land dance numbers. Streets are glassy. Lights splash. Cars and people don’t exist. Notably: everything works. That is to say, as in Chazelle’s film, the city in these paintings is frozen in pure fantasy, in an artificial memory of what LA never was.

But that doesn’t mean they aren’t true.

Sure, everything here is totally contrived. Yes, the paintings were made on the Warner Bros. lot (where Israel keeps his studio), an iconic factory of cultural engineering. Yes, they were painted not by Israel himself, but by his ostensible assistant, the last remaining artist in Warner Bros.’ Scenic Art department, a place once known for painting the backdrops that manufactured cinematic reality. And yes, they’re untethered from time. Showroom, for example, depicts the Googie-style Casa de Cadillac dealership in Sherman Oaks with an Escalade dating to 2021; Gas Station shows the Beverly Hills 76 – a Mid-Century Modern wonder – with the price of a gallon at $1.59, situating it sometime around 2001 (though possibly earlier, since that specific station runs hot), yet with a pump model from 2020; and Chateau Marmont presents us with an Angelyne billboard that first appeared in the 80s, alongside an Apple ad from the mid-aughts.

Alex Israel, Troubadour, 2024. © Alex Israel. Photo: Josh White. Courtesy of Gagosian. But Israel isn’t trying to hide the artifice. He emphasizes it every step of the way – in lore, process, content and color. Some of his paintings’ dimensions are even directly proportional to cinema’s 16:9 widescreen ratio, and others to the billboards that dot the Sunset Strip, once again pointing to that which is constructed, sold, and nominally fake.

It’s precisely because these paintings are so wholly contrived that they become true. Israel leans into the city’s cliché—its fakeness, its artificiality—to highlight its depth. Vapid, you say? How about we empty it out entirely, then smooth it over and paint it like a static backdrop on a soundstage? The move is clever and conceptually sound, and it allows us to at once realize the incredible familiarity we have with our city, while also recognizing its impossibility. To live in LA is to constantly wake up from a dream you’d rather remain in. It’s not so much nostalgia as it is the stuff of romance, and of tragedy.

The paintings don’t go much further than this, and I’m not sure they have to. I could, however, stretch the show a bit further and note the fact that, at their most fundamental, these paintings are glorified depictions of LA real estate, which happens to be the source of Israel’s family fortune (his father is the developer Eddie Israel). So, while there is a base note of reverence throughout, maybe there’s also a tinge of guilt by association, of complicity. After all, these landmarks and their iconic features, not to mention the subcultures associated with them, will inevitably get lost in the very wave of real estate development that allowed Israel the opportunity to paint them in the first place. In other words, without this city, these paintings wouldn’t exist, but without these paintings, perhaps the city would.

Alex Israel: Noir

Gagosian

456 N. Camden Drive.,

Beverly Hills, CA 90210

February 6 – March 22, 2025 -

Michelle Uckotter

at Matthew BrownThere’s something in the Los Angeles air recently that’s been conjuring the ghost of Charles Manson. He has been coming up in conversation frequently (or maybe I am bringing him up). California’s back on the national stage for its hippie-turned-fascist tendencies. Utopian visions morph into murderous cults à la the Zizians. The inherent contradictions of the “Golden State” are getting blown wide open. Another possible culprit for the Manson discourse: Michelle Uckotter’s show “Moviestar” at Matthew Brown.

At the opening of “Moviestar,” everyone is asked to remove or cover their shoes before stepping on a grimy mustard yellow carpet. I get a whiff of cigarette and briefly wonder if the smell is real as I seem to be within some sort of 1970s set (crowds of people are in fact smoking inside). Sculptures of cardboard boxes with chandeliers haphazardly tumbling out are situated in the room like discarded props—and I catch a glimpse through the crowds of a striking Uckotter painting.

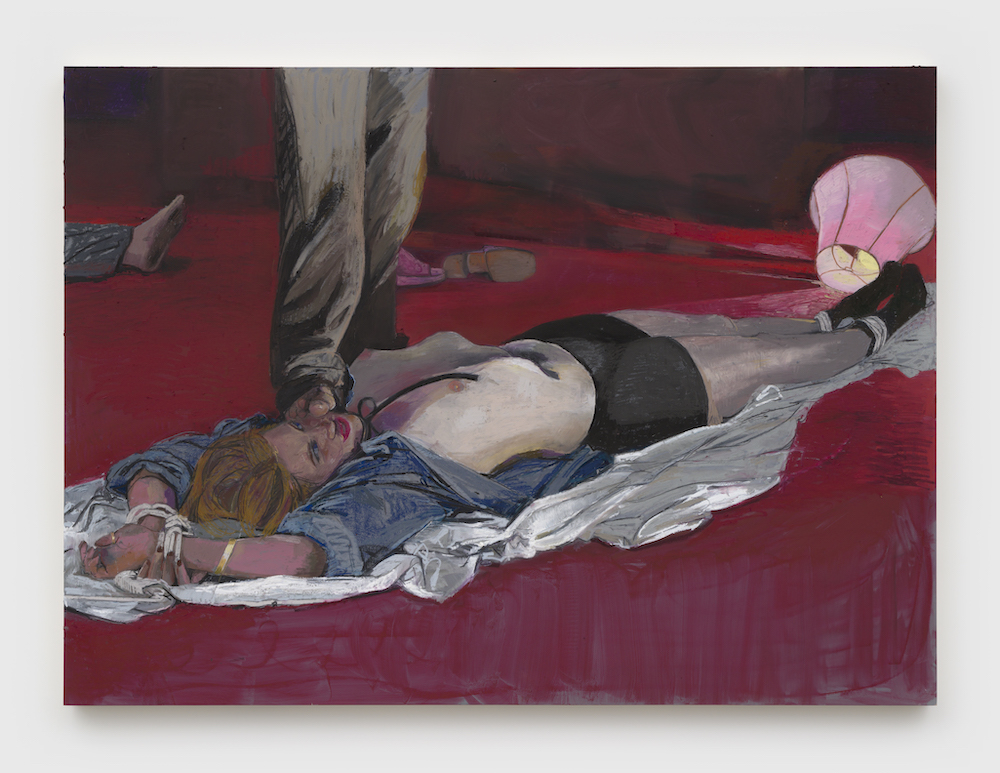

“Moviestar” at Matthew Brown is just one segment of Uckotter’s takeover (the darling of Frieze week!) of Los Angeles, the others being an identically titled show at Marc Selwyn and a video screening at Now Instant theater in Chinatown. Uckotter has traded in her paintings’ previous recurring attic setting for a middle-class mid-century living room, or perhaps we have simply wandered downstairs. At Matthew Brown, we are in a living room, stepping on its carpet, looking at paintings of a similarly carpeted space. What unfolds in the paintings, adapted from stills from the video, is a night gone off the rails, a crime scene, or maybe just a dark and twisted sexual fantasy. The women of “Moviestar” are in compromising positions, but whether licking a gun, tied up, or doing the tying up, they emanate a manic power.

I call them paintings because the work does contain oil paint, but Uckotter’s scenes on panel lie somewhere in between drawings and paintings. Pastel is layered atop oil paint, and scratchily articulated figures that from a distance snap together, turn into a controlled chaos of lines and scribbles close up. The oil pastel is waxy, and while matte from straight on, it catches the light when the viewer shifts angles. Paint is treated as if it’s the same substance and emerging from the same tool as the pastel. The boundaries between the two blur, distinguishable only upon careful examination. The sculptural clay-like quality of the pastel produces chalky flecks of byproduct, chunks of which appear at the edges of marks where Uckotter has pressed with great force. Like the white cap of a wave, the excess pastel reveals a turmoil and intensity.

Michelle Uckotter, The Lady with Gun, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown. In The Sot (2025), a woman is splayed out, bisecting the frame, hands and feet tied, a foot pressed against her face. Her shirt has been ripped open to reveal a bare chest. This woman is playing to the camera or perhaps the camera is playing to her. Uckotter’s framing is ripe with a lustful gaze. The violence depicted isn’t quite frightening; it’s evident that this is merely a performance. These girls are “movie stars” acting as victim, killer, musician, or psycho. And I don’t know if I quite buy the verisimilitude. While denied access to any straight-on gaze, we have body language and composition to go off of. The subjects are equipped with an unnatural assuredness.

Beyond a few scratches, bodies remain intact or are mysteriously slumped over. The implication of body horror gets absorbed into the surrounding scene and furniture. The saturated red carpet furnishing the floor in the paintings bathe the room in a nefarious bloody glow. Glasses, bottles, and decanters, filled with a syrupy red wine, are strewn about. The dingy, green carpet in Dream (2025) is patterned with pink and magenta rose buds that appear like open wounds, with the surrounding carpet turning a bruised yellow and gray. In The Lady with Gun (2025), a lamp, the shade perched at an angle, drips with spots of red. The red resembles scratches on a body, though it’s questionable whether this is blood splatter or the worn-out shade’s stray threads. It’s not the only disturbed lampshade. In The Sot (2025), a fallen shade sits beside its captive companion. Both shade and figure are pink-tinged, their bodies equally exposed. At Marc Selwyn, a lamp gets its own portrait, in which it lets off a thick, snotty, chartreuse glow.

The Manson murders, the epitomic Los Angeles murder spree of the 20th century, hover over “Moviestar.” What strikes me about the similarities between “Moviestar” and the Manson murders is less visual or temporal—hippies, pig noses, drugs—and more the cinematic collapsing of truth and fiction. The phrase uttered by Hollywood elites in Tate and Polanski’s circles, “live freaky die freaky,” is apt for Uckotter’s girls.

Michelle Uckotter, Dream, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown. I don’t quite know how to situate the relationship between the three parts of the show. If Matthew Brown is a bacchanal of decaying femininity, Marc Selwyn offers the grimy masculine, populated by men with sweat-clumped hair and a single female torso nude. The show at Selwyn is stripped down, having exchanged sculptural ornamentation (only a single chandelier here) for a bare-bones display. The operatic Matthew Brown presentation overshadows it, sidelining it as supporting character.

Then there’s the video. I almost didn’t want to see it lest it bring about some kind of narrative clarity. There is some amount of inevitable disappointment at getting access to the paintings’ source material. A committed period piece peppered with strategically placed anachronisms, Moviestar (the video) (2025) follows careerist artistic types encountering a psychotic hippie home invasion. The anachronisms in dialogue and dress pleasantly destabilize the precise set dressing. In the painting “The Threesome,” a man, tied up by two women, sports a knuckle tattoo that says “true.” This paradox, the untruth of a historical inaccuracy that says “true,” speaks to the intent of the project at large. It is collapsing time, fictionalizing historical events, and exposing violence’s manifestation of unconscious fantasies. Etched into these paintings is a truth of sorts.

But it’s only of sorts. What is a director/painter if not a cult leader, promising the truth while delivering an illusion. Pulling the strings, getting others to do your bidding, emotionally molding your underlings. Manic smearings elevated to godly proportions. I’ve joined the Uckotter cult.

Michelle Uckotter: Moviestar

Matthew Brown (and parallel exhibition at Marc Selwyn)

631 N. La Brea Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90036

February 13 – March 29, 2025 -

Jacqueline Humphries

at Matthew MarksWe recognize the legacy Jacqueline Humphries is working from the moment we set foot in Matthew Marks’ two gallery spaces; yet something throws the viewer slightly off. It’s the echt gestural vocabulary of post-World War II art, but as if viewed through a scrim or screen, which in more than one sense it actually is—a highly processed, thoroughly post-modern actuality, in which the processing itself breaks down with pigments dissolving, disappearing, reappearing through, or floating above an interwoven mesh of screens, coding, and emoticons.

The residuum of Humphries’ gravitation towards certain well-defined styles and gestures is fairly manifest—e.g., mid-1950s Philip Guston, Clyfford Still, or color field painters like Helen Frankenthaler. But Humphries resisted the figurative direction of so many of her neo-Expressionist peers to meet the screen(ed) world of the media-saturated Pictures Generation head-on. Four decades later, her interrogation is even more foundational, almost ontological: not simply the perception, projection, or reflection—the materials of her art—but messaging, meaning, and interpretation; the ambiguity of figure and (always shifting) ground; and what one view tells us about the next.

Screens complicate the traditional picture plane; and Humphries throws the viewer through a screen (or screens) very darkly from the onset. JH456 (all paintings 2024) floats a volcanic storm of black cinders over Still-esque pours and drips of crimson and anthracite against a fine mesh that itself shadows chalky blue ‘shadow’ pours or underpainting. And as for the pours—are they actually? Or just more stencils? The artist’s title/signature initials in the upper-left quadrant just barely gives that away. Gravity will have its way in this ambiguous domain of the pre-determined and free-floating. (Or will it? Humphries might conceivably rotate the linen panel to further confuse or ‘cross-examine’ figure or ground or both.)

Jacqueline Humphries, JH123, 2024. Photo: Ronald Amstutz. © Jacqueline Humphries. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery, Los Angeles. The largest of the paintings, JH123 (127×114 in.) gives us a waterfall of slightly pallid rainbow pours in amber yellows, pale blues, and pinks, from the center of which looms a cluster of black hulking, almost exploding fountain of pours—conceivably as stenciled as other parts of the painting. But pulling back from the painting dead center, we register horizontals parallel to the upper and lower edges; and we’re suddenly made aware of another layer of painting/stenciling that could make something else of this entirely. It’s impossible to say whether Humphries played with a Johns style array of block letters or numerals (or if such effects were stenciled on and immediately washed over); but it was hard not to be reminded of those classic fluorescent half-tone Colby Co. posters that once blanketed southern California, advertising everything from rock concerts and prizefights to business liquidations and the 2012 Hammer Museum Made In L.A. biennial. Here (as elsewhere), Humphries floats a quasi-anamorphic stencil of her initials and assigned number for the work (or series of works), as if to assert both authorship and a certain detachment from these ambiguous and slightly volatile conundrums.

Amid these first few paintings, we start to reconsider relative definition and uncertainty as it enters into the moment of conception and execution; that everything is mediated between image and object on either side of lens and retina. That uncertainty (and some drama) is at play in “Crimson Shatter”✨, which bears some resemblance to JH456, but on a slightly larger scale (111×100 in.), magnifying its impact. Their similarity alone throws the determination of pours/drips and stencils (as well as underpainting) into question—the three larger stenciled pours of JH456 here reduced to a kind of rent in the ‘fabric’ (that ‘bleeds’ black), and even the ‘sparkle’ emojis screened mostly in black and sinking into the underlying screen mesh. Between this vivid crimson—slightly brighter than actual blood—and that coal black of JH456, it’s hard to resist a mental leap to associations with disaster. Paler, cooler underpainting, whether pink, blue or grey, only seems to magnify the violence.

Our culture has evolved a fascination with encoding clearly shared by the artist. But Humphries also seems conscious of the dubious filtration of screens, a kind of passive suppression such media ‘shorthand’ can willfully or inadvertently promote. The pours (conceivably accompanied by other applications, whether by stencil, brush or both)—mostly in deep red—are almost entirely obliterated beneath a larger black mass in JH123✨, except for a cloudy cluster of red that drips to the edge of the panel; and suppression seems to be half the point; also fracturing.

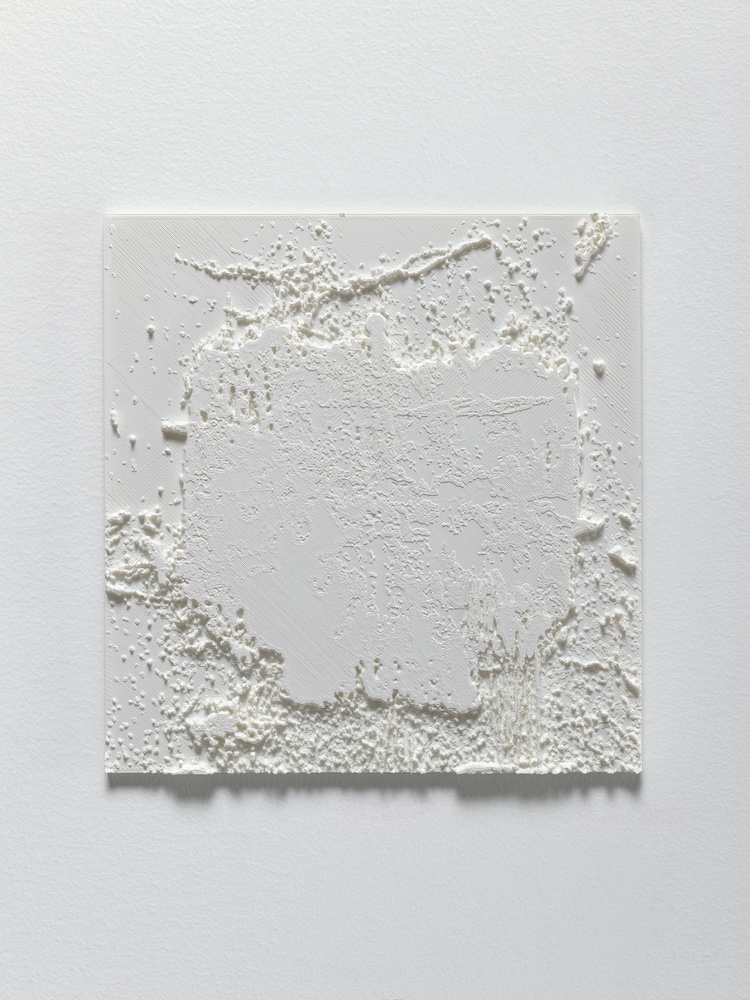

A 3-D printed panel in white enamel on PLA (a kind of biomass plastic), Untitled (2025) recapitulates (at about 10 percent scale) the screen/pour/drip imprint of JH123✨, with the clear difference that the sparkle emoji screen printing—deeply embedded, though almost ghosted (grey)—in the painting, scarcely appears in the panel. It made for a coolly analytic bridge between the slightly violent chromatic drama that seemed to scream off several of the linen panels preceding it, and the latent violence that wafted off of Humphries’ series of aquatint etchings of Paul Schrader’s scenographic outlines (all handwritten by the director in blue and red ink on yellow legal pads)—clearly an hommage to the director/writer. (Humphries is an admirer of the filmmaker—apparently not just for his films, but also his insight into classic noir cinema.) Mishima and the iconic Raging Bull to one side, the range of Schrader’s film work is riveting.

Jacqueline Humphries, Untitled, 2025. Photo: Ronald Amstutz. © Jacqueline Humphries. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery, Los Angeles. After the drama in the main gallery, the works in the galleries facing Santa Monica Boulevard seemed almost coolly elegiac. An all-over stenciling of large green dots that seemed to uncannily cluster like grapes over dripping black puddles and pours in a smaller Untitled were a nod to Roy Lichtenstein’s Benday dots and his own comic-book graphic send-ups of AbEx heroic gestural brushstrokes—these, including equally organic-looking splotchy white overpainted drops in the upper section, decidedly less heroic and almost deliberately pathetic.

One of the most striking paintings in the entire show) was a second JH123✨, in which the sparkle stenciling takes on an exceptionally ironic cast. That suppressed sparkle quietly underscores Humphries’ re-cast definition of the work—articulating form and processing into a far more complex statement. The tumbleweed mass of black pigment of the first painting is rotated slightly off center here, with new bits of underpainting and drips or ‘spray’ exposed (although the lower edge is strikingly similar). Beyond rotating the stencil(s), additional screens, stencils or under- or overpainting shadow the upper-left portion of the off-center mass, almost bleaching away its right section—placing this ‘absent’ mass at its rose-pink scrimmed center.

This latest body of Humphries’ work comes at the viewer with an almost existential directness and estrangement. Without sinking into the quicksand of over-interpretation, disaster seems to float towards us amid these ambiguous archipelagoes of form and re-cast, re-framed, re-screened gesture. But the work also moves the viewer towards a reconsideration of the ‘ground’—or the void beyond the ground. Humphries meets her viewer in a familiarly skeptical terrain, where fear or dread are less significant than the disintegrated actuality—the flip side of the ‘sparkle’, if you will, which is an infinitely twilit absence.

Jacqueline Humphries

Matthew Marks

1062 N. Orange Grove

Los Angeles, CA 90046

February 20 – April 5, 2025 -

Ramsey Alderson

at Tiffany’sIt’s a matter of complete coincidence that Ramsey Alderson’s show “d’Or” at Tiffany’s—an East Hollywood artist-run garage space programmed by Adam Verdugo—coincides with the 17th anniversary of the notorious Emos vs. Punks Fight held in Mexico City’s Glorieta de Los Insurgentes in early March of 2008. The famed altercation, which saw young Punks and even younger Emos collide in a pedestrian-only roundabout of downtown Mexico City, was the flashpoint after weeks of anti-emo violence across the Mexican republic fueled by newly emergent online avenues. Animosity built up towards the effeminately fashioned emosexuales (the unambiguously homophobic name the Punks came up with for the Emos, one phoneme away from the Spanish pronunciation of homosexual) until hundreds of youths from both sides clashed in the glorieta.

The figures in Aldseron’s paintings, while not too different in their fashion from the Emos in grainy archival flip phone videos of the fights, belong to a faction unknown. They are not the collective alternative, but the lone actors. Whatever terminology may apply, they are undeniably legitimate emosexuales, presented here in intimate moments immune from ridicule or categorization. Bath For Our Foredaddies (2025), the central painting of the show, depicts two spikey haired boys interlocked in a bath, gazing at the viewer, toasting dainty goblets. There is something totally inverted about the bathers. Their interests lie beyond being public agitators, their provocations exist only for each other. Their demonstration is leisurely, and it’s a private demonstration. A worthwhile question is raised: Are they really like that for the attention?

Ramsey Alderson,

“d’Or,” exhibition view, 2025. Photo: Lizzie Klein.

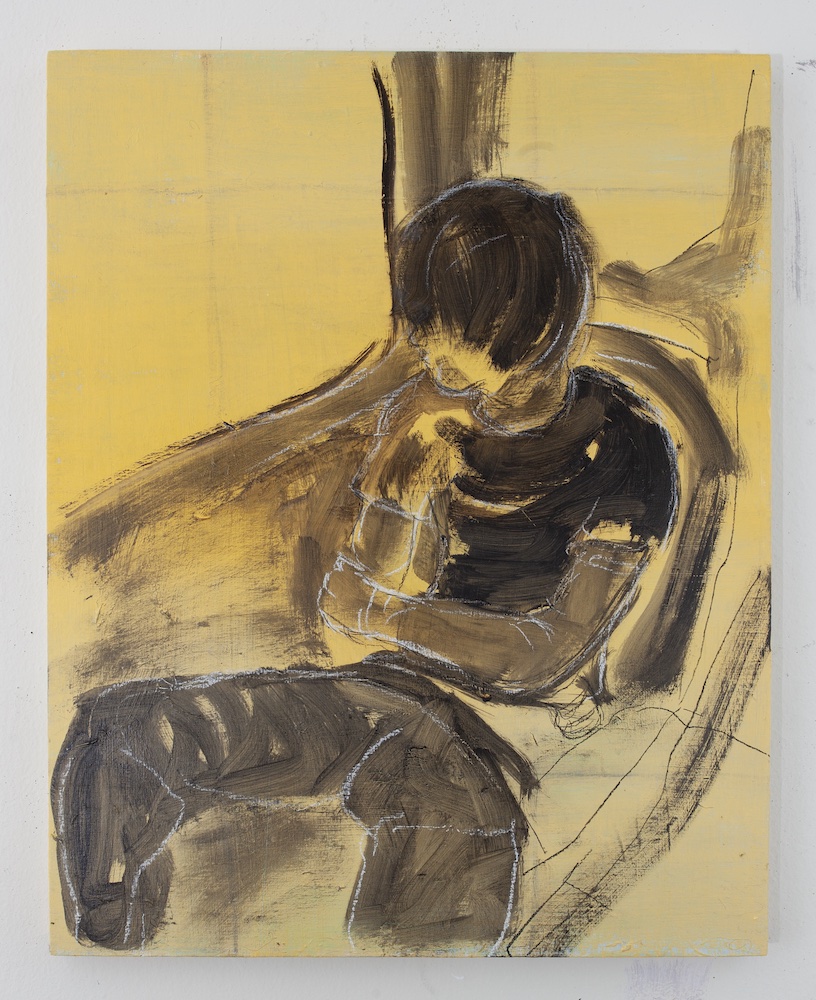

Courtesy of Tiffany’s.In the three other works, Alderson’s nonchalant yet assertive style occasionally exceeds the modest sizes of the panels the figures find themselves in. The boys are also tightly cropped, unaware of the confines of their own frames. Substantial areas of the panels are covered in single tones of lusterless acrylic, and one figure is rendered only through thin overlays of ink and charcoal at varying opacities over a golden ground This is complemented by areas of special sensitivity, like the blue hair that is more robin’s egg than Manic Panic in Mmm (2024), or the white outlined pants and sleeves on a pensive train rider in d’Or (2024). The idler and the traveler both bask in their own limp wristed flamboyance, while still maintaining the same lack of concern for the viewer as the bathers.

Even so, their stage is set. The garage door at Tiffany’s is open when the show is. During evening viewing hours, each wall is paired with its own spotlight, which project three eerie focal triangles against the lacquer-red Alderson and Verdugo elected to paint the interior walls. On the opening night the floors still smelled of the dark brown stain used to turn the plywood viewing platform into something more seductive. These gestures read as carefully conceived abutted against the implied indifference of the femme boys in the paintings. The impression of the garage is not unlike a craftily and economically furnished dingbat apartment outfitted with odd color belonging to an aging dandy. Or maybe it’s just a weird mismatched midwestern finished basement. In any case, Tiffany’s seems to recognize these paintings’ place—somewhere within an indulgent tableau of desire and indifference.

Ramsey Alderson: d’Or

Tiffany’s

861 N. Alexandria Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90029

February 8 – March 22, 2025 -

Gregg Bordowitz

at The BrickI left Gregg Bordowitz’s recently-closed exhibition at The Brick, “This is Not a Love Song,” thinking the same thing as upon leaving The Brutalist: “I didn’t know it was going to be so Jewish.” In both, the artist’s Jewish identity weaves through a deep consideration of form as such. I might even cheekily add that in both cases, the interest in form manifests in concrete specifically. The Brutalist’s eponymous brutalist, László Tóth, uses concrete to maybe (?) represent the suffocating brutality of Auschwitz. Bordowitz, on the other hand, has a longstanding interest in concrete poetry. This is not a review of The Brutalist but one further comparison is perhaps warranted. The film’s climax centers on the completion of Tóth’s brutalist church/community center and the antagonist presumably committing suicide somewhere inside, turning the monumental structure into a tomb as well. In an epilogue, Tóth’s niece describes the building as a redemptive allegory of Auschwitz. In other words, the film culminates in a tomb for a body that is never shown and a story of redemption for the most indescribable of sins. A rather Christian Judaism, all told.

I bring this up only to contrast it with the approach to Judaism taken by Bordowitz, one more active and paradoxically, more architectural. Bordowitz’s Judaism is not so much represented as it is embodied—a structure for living. The exhibition is anchored by a freestanding wall positioned diagonally in the center of the gallery. Bordowitz’s poem, Bougainvillea Calliope, is affixed directly to both sides of the wall. It is governed by Bordowitz’s self-imposed rule that each line be exactly ten syllables. Lines such as “LASAGNA HOLIDAY IMMIGRATION/ HOSTILITY RECIPE LEGACY” are illustrative of the poem’s taut blend of the nonsensical, political, and personal. The poem’s balance of formal rigidity and quasi-abstract meaning is paralleled in the print series, entitled Tetragrammaton, hung on the wall, which occasionally obscure sections of the poem. Though they are all abstract, the series depicts the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter Hebrew theonym for the name of God. Here too, the formal constraints of language overflow with an irrepressible passion.

Gregg Bordowitz, “This is Not a Love Song,” exhibition view, 2025 at The Brick. Photo: Ruben Diaz. Courtesy of The Brick. As an academic, AIDS activist, poet, and politically-inclined video artist, language has always been central to Bordowitz’s practice. Here though, the written word functions as a sort of necessary boundary line. The rules it establishes for sensemaking serve to delineate what exceeds it, what cannot be accounted for. In this way, it is not simply an inert representation but a site of energetic activity. Another piece, Continuous Red Line, made of a red strip of tape, running inches off the floor along the gallery’s perimeter operates similarly, linking each element of the exhibition into a whole. The artworks are thus in conversation with one another though this does not require that they find any resolution. The line is perhaps the ur-form of art, representing form as such and the fundamental building block of artmaking. Both the scrawled lines of quasi-legible Hebrew on each print and Continuous Red Line are thus testaments to the line’s dual functions as a form and a process, an idea echoed in the exhibition’s accompanying booklet. There, Bordowitz writes that “form is both a process and a state.”

This is echoed in the exhibition’s curation itself. Placing the wall in the gallery’s center animates the typical flatness of text and prints. Additionally, the wall’s placement forces viewers to ritually circumambulate the work. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heshel, who Bordowitz quotes in the booklet, famously said that Judaism does not build cathedrals in space but in time, through the affirmation of ritual. In other words, form emerges out of communal repetition. This idea is closely related to a central tenet of Bordowitz’s political belief, cultivated through years of AIDS activism with ACT-UP, that the personal is political. Both theories conceptualize the individual’s actions as a fractal piece of a much broader community movement. Both ideas suggest that meaning is found in action itself, not finality. At a moment when Jewish identity is in danger of being essentialized (or concretized) into a hard nationalism, Bordowitz’s work suggests a softer Judaism, one that cannot crack as a result.

Gregg Bordowitz: This is Not a Love Song

The Brick

518 N. Western Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90004

February 2 – March 22, 2025 -

David Hammons

at Hauser & WirthI went in blind to David Hammons’ Concerto in Black and Blue (on view for the first time since its 2002 debut)—both literally and figuratively. When I pushed back the heavy curtain shrouding the gallery, darkness swallowed me. I couldn’t pull out my phone to navigate by its glow, nor could I use it to look up additional context for the exhibition—prior to entering, I had been asked to stow it in an automatically locking pouch. My only option was to switch on the miniature flashlight I had been provided and cast its blue beam before me in search of the show. Little did I know it had already begun.

Several other patrons, also wielding flashlights, materialized as I stumbled ahead. Had they come in from a separate entrance? Not quite—the gallery, it seemed, comprised several vast rooms, each one with sky-high ceilings. There were no signs or markers to direct us toward any predetermined path. We simply had to let the silence move us.

The Oxford New World Dictionary defines a concerto as “a musical composition for a solo instrument or instruments accompanied by an orchestra, especially one conceived on a relatively large scale.” The sole sounds in this concerto were hushed voices and the echo of footsteps against concrete. Yet the definition does offer a framework for interpretation: the solo instruments were the blue lights; the orchestra was the black background they played against.

The very presence of darkness suggests some hidden objects or entities; to obscure means to make dim as well as to conceal. It makes sense that I should instinctually anticipate some surprise. The next room, I was always sure, would contain a potential discovery: maybe a miniature in a far-off corner, or a stories-tall installation that would justify the exhibition’s scale. For a moment, my party believed we had found a sculpture, about the size and shape of a person; it turned out to be a living, breathing security guard, sentenced to standing still amidst our shuffling.

When you stare at nothing for long enough, everything becomes something. Soon, I was shifting my focus from the open space to its container. Minor irregularities on the walls held the significance of hieroglyphs. Electrical boxes could have contained clues. A floor-to-ceiling garage door proved particularly awe-inspiring: after beholding so much blankness, the textural interruption felt, well, orchestrated. I craned my neck, looking for cracks where the white light of the clouded March sky might have seeped in. I found none.

A full sweep of the premises revealed no secret totem. Making my meditative rounds, I felt a flicker of disappointment that my search should turn up dry—but had it really? Perhaps the perpetual craving for some tangible, cathartic conclusion is part of what Hammons set out to interrogate. In the tradition of John Cage’s 4’33” (1952), the absence of a spectacle can be a spectacle in and of itself. If a tree falls in the forest, does it really make a noise? If no blue lights bounce off the gallery floors, does the concerto play on?

It is tempting to view the show, all-consuming as it is, as its own entity apart from the world, but one experiences it anew when taking into account the artist’s prior interrogations into race and Blackness. Hammons is known for using color to reframe the viewer’s understanding of familiar images: his painting How Ya Like Me Now (1988) depicted Jesse Jackson with white skin and blond hair, while Untitled (African American Flag) (1990) presented an American flag in the red, green, and black of the Pan-African Universal Negro Improvement Association, founded in 1914. Additionally, Hammons has used negative space in sculptural installations to great effect: In the Hood (1993), which appeared on the cover of Claudia Rankine’s poetry collection Citizen (2014) in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s murder, consists of the hood from a hoodie nailed to a wall, the wearer absent or invisible. Considering all this, the piece reflects upon what it means to “see color”—not just an encounter with blackness, but an encounter with Blackness.

Much critical praise for Concerto in Black and Blue concludes by celebrating its collaborative nature: the intersection of flashlight beams becomes a gesture of intimacy or interrogation between strangers as their identities are subsumed by shadow in service of the art they’re unwittingly creating. Yet I’m more drawn to the work as a conscious collaboration with darkness. By restricting the sense by which we most typically experience art, Hammons forces us to look at what we can’t, or won’t, see.

David Hammons: Concerto in Black and Blue

Hauser & Wirth

901 E. 3rd St.,

Los Angeles, CA 90013

February 18 – May 25, 2025