Your cart is currently empty!

Ron Athey at the ICA Los Angeles “Queer Communion”

I’m on the freeway traveling through the San Fernando Valley to see the Ron Athey exhibition of art, documentation and ephemera called “Queer Communion” at the ICA in downtown Los Angeles. All of the LA tropes are in place: It’s a sunny and clear June day, the hills of Griffith Park are dry and brown, the plentiful commuters spawning upstream on the 5 all slow to see a majestic Honda engulfed in flames in its natural habitat. It’s all a beautiful sight for plague-weary eyes. Athey’s 40-year praxis along with his countless collaborators have a part in this exquisite corpse known as LA. Although Athey’s international reputation portrays his performances as extreme and on the bleeding edge of the fringe, this new-found institutional embrace of his work in an historical frame makes his densely conceptual ideas about art and existence more accessible than ever before.

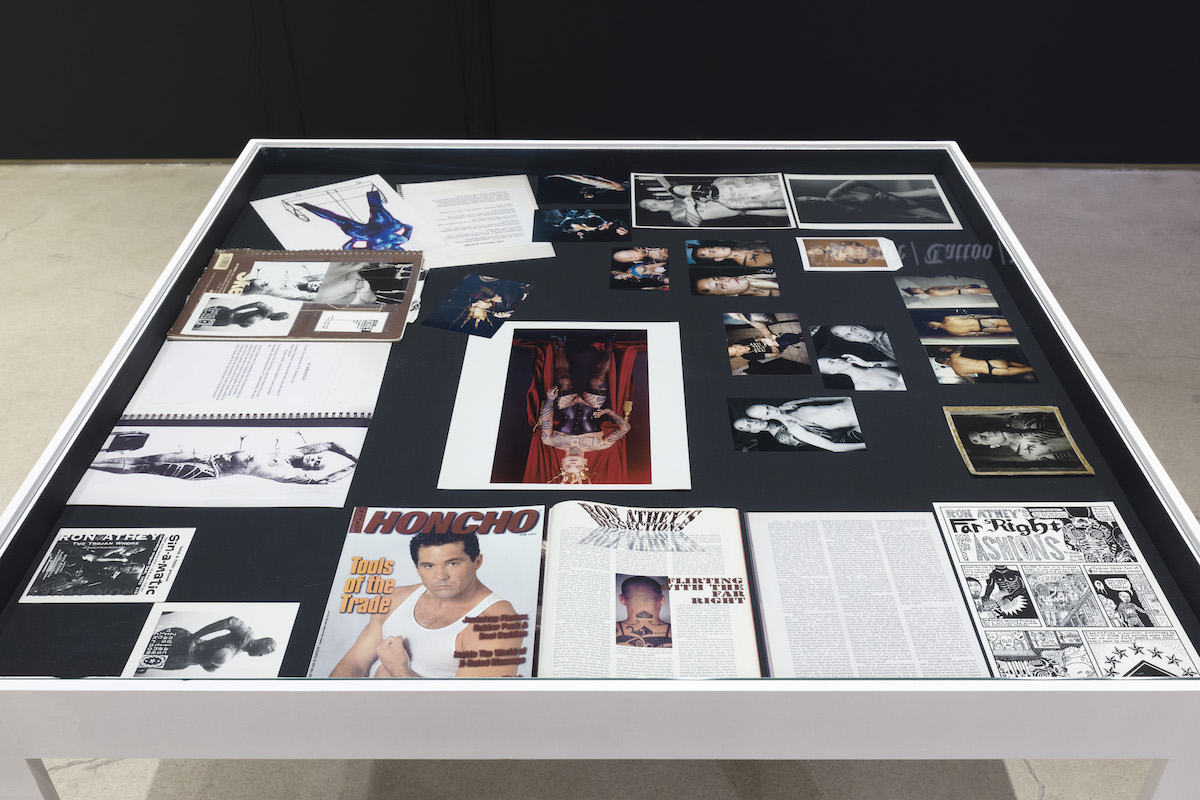

Inside the ICA, the show, guest-curated by Amelia Jones, is smartly divided up into several thematic sections playing out like chapters in the Book of Ron. It works well as a complement to the publication of the same title edited by Jones and Andy Cambell. There are sketches, personal effects, photos, posters, costumes, performance objects and of course documentation of several performance pieces. The themed section I encountered first is called “Religion and Family” and is the best place to begin the journey.

Amongst the very personal objects and documents are not only storyboards and writings, but also family photos and intimate relics that display a collage of the artist’s origins. “Religion and Family” opens for the viewer the often-sited early years of Athey’s work as an artist who has instinctively used his troubled biography as fuel for art-making. Included in this particular vitrine are posters and flyers from evangelical revivalists like Miss Velma and Dr. Lee Jaggers. For the viewer, this particular collection of life objects sews together a river with diverging flows. First is a young Athey with a hospitalized schizophrenic mother, missing an absent military father (Ron Sr.), raised by his maternal grandmother amongst Pentecostal extremists who search far and wide for radical religious zealots to learn from and to show to the young artist. Second is the compulsion to honor lineage while reinventing his own views of things like channeling spirits or fire and brimstone Evangelicalism. Extracting the value of the ritual without the judgment, it seems as though he saw the power of the chosen family and the weakness of blind faith. A spiritually precocious young Athey was considered to be a promised child in this context and would jump up and shout out in tongues during tented revivals. Other parishioners would lay their hands upon him as a showing of respect to the Lord who had given Ron such gifts. Here, Jones makes visible the lifelong path Athey has laid out for himself in these early years, one of a loving leader in spirituality, here to guide other lost souls.

Joyce, a 2002 performance named after Athey’s mother, was presented in London and included collaborators Sheree Rose, Patty Powers, Lisa Teasley, Gene Gregorits, Taj Waggaman, Rosina Kuhn and the late Hannah Sim of Osseus Labyrint. The work is about the mad matriarchs that raised him, with each one depicted by varied on-stage performances while three channels of projected video content portray harsher aspects of their personalities. The installation shows documentation from Joyce, and it also presents the original video content on its own, while very cleverly synchronizing it with its identical projected material in the documentation footage. This is the first place where the viewer will notice the use of older video monitors to overtly illustrate the difference between documents and live works, asserting that these are mere representations of the work and not an effort to replace the lived experience.

The next sections blend well together as the viewer is moved through the chapters in what Jones refers to as a recursive chronology, where Ron often pulls from past experiences. With the section “Club/Music” we see the very early foundations of the artists’ compulsion towards the performative act, writing and most importantly finding like-minded communities to escape his past, and to survive the different waves of queer hate that became even more omnipresent during the early days of the HIV pandemic.

The most mindblowing thing to learn from this portion of the show is how truly original and diverse were the different lives that Ron was able to live. He and his boyfriend Rozz Williams lived together in Rozz’ parents house in Pomona not long before Williams founded the band Christian Death. He began doing performances with Williams as Premature Ejaculation, and the venues for this work were already presenting all the post-punk bands alongside fetish nights and cabaret-style hot messes. Here he also took on the role of organizer and curator of sorts as he would mash together these floor shows with local artists like Vaginal Davis, Buck Angel, Catherine Opie and Bob Flanagan.

Into the ’90s, Athey continued with a similar strategy in the BDSM community. In these underground spaces Athey had again found a setting for his ideas and discovered the crossover that can exist as his work continued to evolve and expand. This expansion attracted the attention of Jesse Helms, a senator from North Carolina. Helms took to the senate floor to yammer on sloppily while describing Athey as handsome and telling everyone about how Athey exposed a live audience to his HIV-positive blood. Inaccurate retellings spiraled out of control, leading to a Republican effort to defund the NEA—reactive cancel culture before it had a name. In truth, the performance 4 Scenes In A Harsh Life presented at Patrick’s Cabaret in Minneapolis, received the tiniest amount of NEA funding indirectly through the Walker Art Center. It was barely enough financial support to produce flyers for the show.

When looking at the mass of “Queer Communion” and the catalogue, the visitor can easily see Athey in the role of the guru, not just as someone who attracts followers, but as someone who creates safe spaces for communities to develop. In the guru’s truest form, his self-found and deep knowledge of a broad range of things like history, religious practices, philosophy and existentialism originates from an authentic provocateur, and followers seek that out.

Finally, the exhibition presents the viewer with objects and documents in a touching tribute to the groups of people that have circled around Athey in various capacities—collaborators, fans, lovers—a patriarch in the best possible sense of the word. It’s easy to see this loving gesture as a “thank you,” but in fact it is Athey who has brought them to him as collaborators and supporters, and it’s hard to imagine the community coming together in the same way without him.

Comments

One response to “Ron Athey at the ICA Los Angeles“Queer Communion” ”

Very narrative and informative article