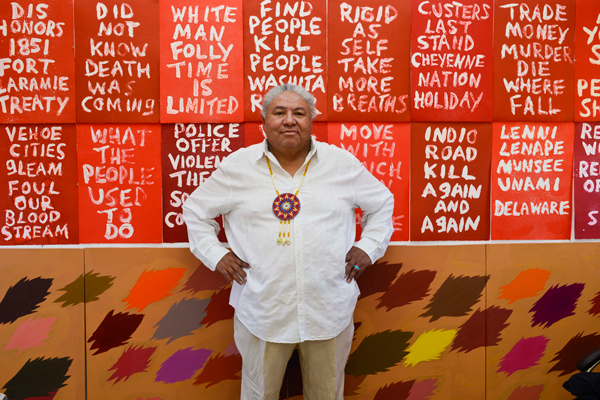

Patricia Watts is the founder and curator of ecoartspace. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on the unceded land of the Tewa people. ARTILLERY: What was the crucial purpose in founding ecoartspace? PATRICIA WATTS: When I came up with the concept for...