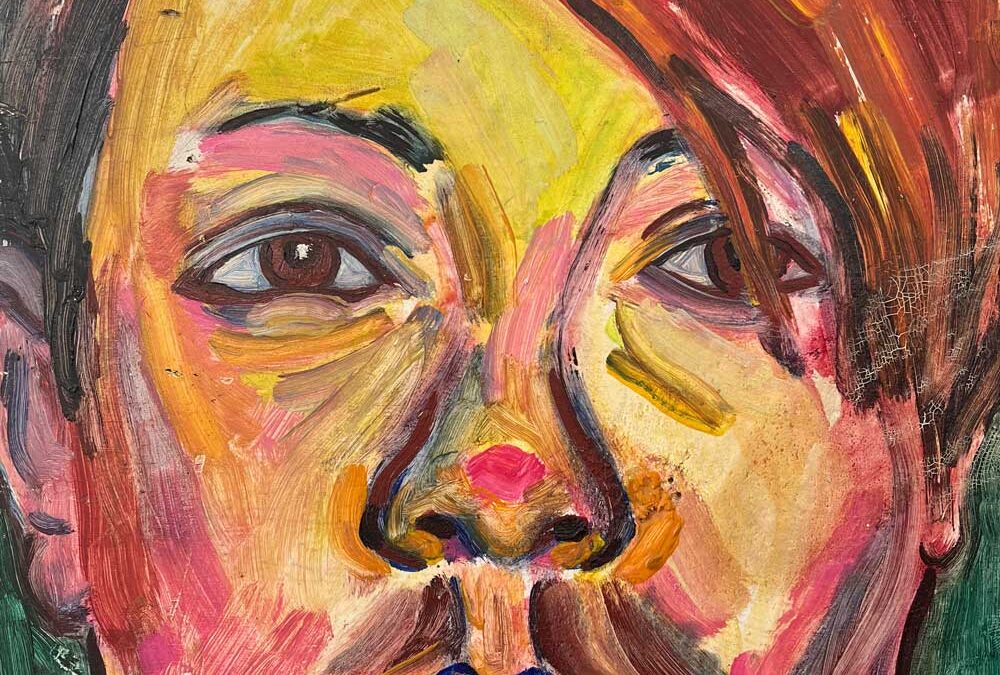

Dear Reader, As long as there are people, there will be portraits. Face it—no pun intended—people are attracted to people. We like to look at ourselves; we like to people-watch; we gaze into our lover’s eyes. Our faces are unique and fascinating: they are who we are....