I hope you’ve had this problem: You like some art somewhere but you hate the social machinery around it.

You know something is good, but the discourse, the nepotism, the snobs, the takes, the informative six-page features, the art history teachers, the leachers, the exiguous creatures in the bleachers, and the limited-edition sneakers: they make you despair.

You love a thing—a thing, an object, not even a person. And to find that love or articulate it, or to acknowledge how much your love of actual people comes down to being able to share that thing-centric love with them, requires intercourse with harsh processes where the sausage of that love is extruded from the great and squealing hog of life in a society.

Loving art in a way that brings it close to your life sounds like something that happens to a maiden aunt in a novel about finding romance on a trip to rural Italy, but it also just sucks—like loving a cat with three legs but no bladder control.

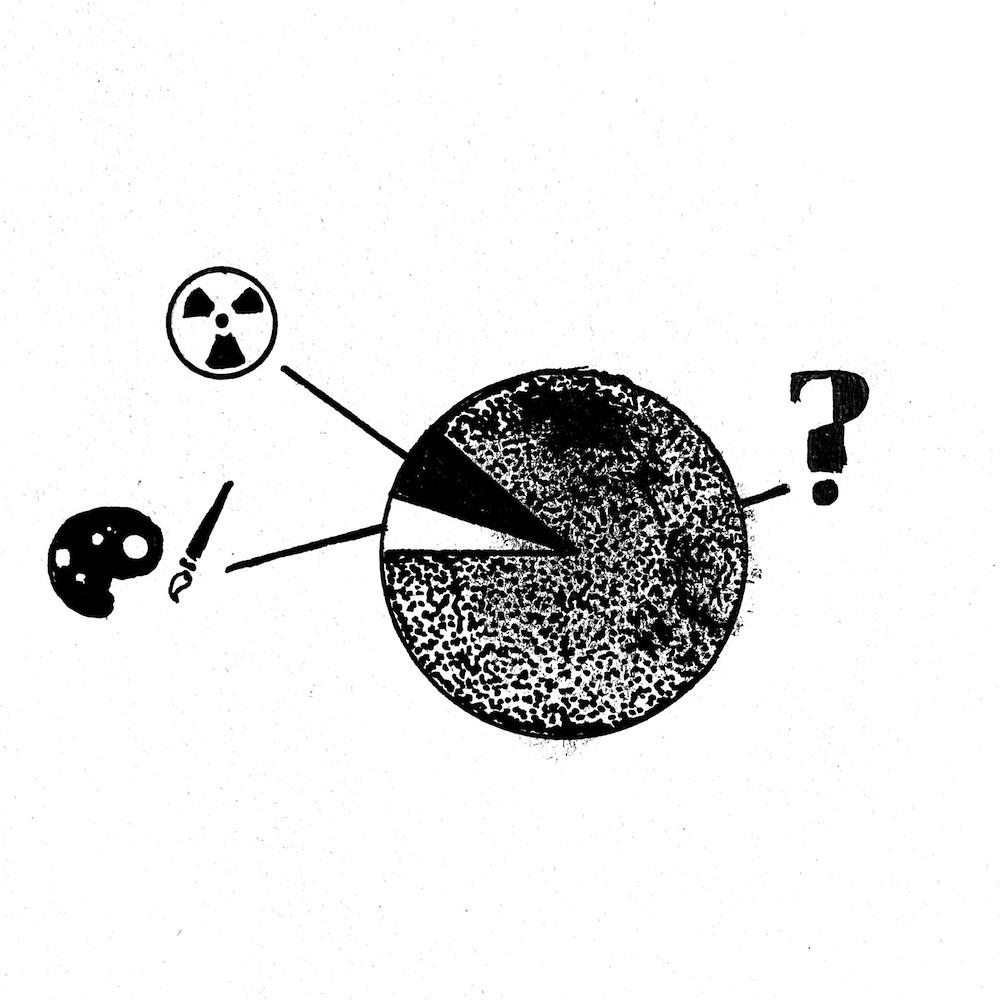

If we can stop being ironic about our relationship to the apparatus of art, so much of what we worry about is the line where the art ends and the bullshit begins.

Thirty-one minutes and 59 seconds into Tár—a film about the downfall of a celebrated fictional contemporary conductor—the titular Lydia sits at a piano and plays a Bach prelude to a skeptical student, monologuing as she plays: “…you hear what it really is, it’s a question,” (as she plays an up-talking musical phrase) “and an answer,” (and a subtly different phrase) “which begs another question,” (a phrase again). “There’s a humility in Bach, he’s not pretending he’s certain about anything because he knows that its always the question that involves the listener—it’s never the answer”.

I like this prelude. I think it is Good Art. I like how Lydia/Cate Blanchett plays. Good Art, too. The skeptical music student agrees (and when rivals agree it is the closest thing we have to truth in the arts) that Lydia plays well. I would even venture so far as to say that despite me knowing fuck-all about classical music that Lydia’s analysis of Bach is persuasive, and maybe I even learned something. Which is good because I know so fuck-all about classical music I had to Google to find out it was a prelude.

And despite there being two hours left to go in the movie that’s all I know for sure about the art-to-bullshit quotient inhabiting Lydia Tár.

This is a pivotal moment in Tár because it is the only time we are assured that Lydia is actually good at anything. Every other second of the film has the same humility its protagonist ascribes to Bach: it just asks questions.

Lydia Tár (born Linda Tarr) at the piano is a pinprick of authenticity in a bloodbath of pose and unproved assertion. She is fawningly interviewed (her answers are rehearsed), she models for album covers (she art-directs them), she dresses carefully (even when not modelling), she offers advice to inferiors (and she is sure they’re that), adoring fans approach her, assistants handle her logistics, she writes something called Tár on Tár, she controls a fellowship and a major orchestra, her relationships with colleagues are lurid and questionable. She is above all high-handed and for an audience that wants to see her with hands held high. In other words: the art and life of Lydia Tár are attended by a tremendous amount of bullshit. And her downfall via social media is due to not doing the bullshit well enough. Because the artist’s enmeshment with bullshit is inextricable.

And at no point are we sure (or unsure) she’s worth all this attention. I’m still not 100% sure what a conductor even does. Don’t all these musicians have sheet music?

To see the film’s achievement here we have to remember what films about artists are usually like. Either the moment of making is undergirded by an advancing swell of inspirational music—and then we know the art’s supposed to be good, like in Basquiat, Pollock or Oliver Stone’s The Doors—or the art is introduced in a deadpan shot with someone in a failed experiment of an outfit ultra syllabically swooning over it—in which case we know the art’s supposed to be silly, like in Velvet Buzzsaw or Ruben Östlund’s The Square.

Portraits of artists are usually either heroic legend or satire, but the problem with real artists is they come unlabeled. Tár lets us sit with that problem. I’m going to say that makes it good.