Amid an ocean of color-mad paintings in Henry Taylor’s three-decade retrospective at MOCA is a colorless painted object: a black typewriter case overlaid with text of thick white coarse brushstrokes:

I TRY To be

Write aint

TRY’n to be

WHITE

Simple rhythmic text that’s plain white on black—but not so simple as one might think at first; this untitled piece registers in my brain as essential. Taylor’s work hinges on the idea needing to tell stories and doing so with a singularly curated empathy.

“Taylor has an interest in people, he wants to know them, to help them, to be around them,” writes LA artist and CalArts art prof. Charles Gaines in the accompanying catalog of the exhibition, “Henry Taylor: B Side.” “Painting portraits allows him to be with people, to spend time with them.”

Spilling over the bottom of the typewriter case and onto its handle are crudely painted front teeth in white paint, baring discontent that’s as present in his paintings as the influence of Picasso. The identity message gets delivered with a smile, but deep down it’s no joke.

I TRY To be

Write aint

TRY’n to be

WHITE

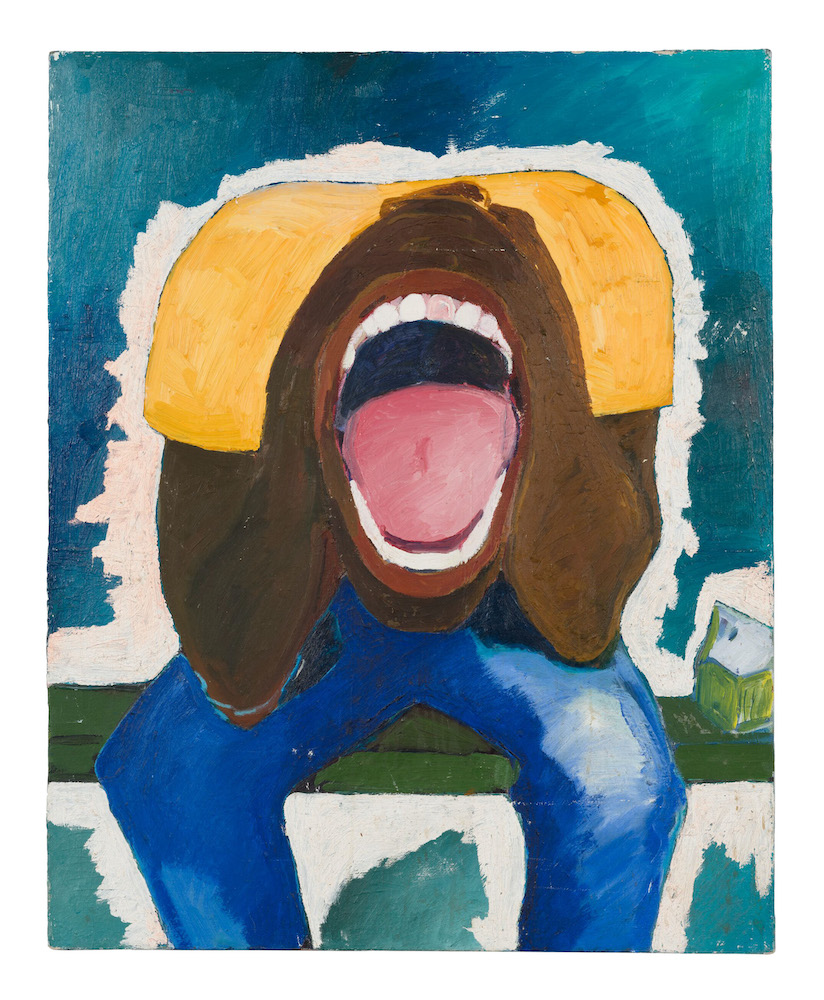

Henry Taylor, Screaming Head, 1999. Image and work ©Henry Taylor, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Jeff McLane.

Taylor, 65, studied journalism and anthropology at Oxnard Community College. He only wanted to tell stories about people—his folks in particular. But journalism is full of complications and potential misconceptions; people think you’re doing one thing when you’re trying to pull off another. Art is unmediated, uncut and from the heart.

Taylor always had the raw tools of expression. His empathy—honed by watching the inherent struggles of seven elder siblings—would rise toward an uncanny level on the strength of working for years as a mental health technician. His Camarillo State Hospital tech gig falls under the umbrella of nursing. This facility (rumored the subject of the Eagles’ song, “Hotel California”) provided Taylor constant interaction with disturbed persons who could not check out and—it almost goes without saying—would almost never leave.

For 10 years this in-the-making artist was friends with the officially insane. He developed lasting relationships with patients who might go mental on a dime. You get your doctorate in empathy this way.

Many of Taylor’s subjects in his portraits are homeless and street people. Like Taylor’s studio in DTLA, my own place of work sits not far from Skid Row. Walk Skid Row sometime, if only its perimeter. If you haven’t had the downtown Los Angeles pedestrian experience, stroll over to learn that—as horrendous and overwhelming a Black place as you imagine Skid Row to be—it’s worse. By a lot. While maneuvering through and around Skid Row’s tents and humanity I avert my eyes and tick the reminder box: our most tangible example of America not honoring its responsibilities for slavery. Right here.

It’s not only poverty-stricken subjects who benefit from Taylor’s deep sensitivity. His characterizations of family and historical figures seem driven by his ability to also elicit by suggestion. When Taylor takes on Black Americans who have died at the hands of police (Philando Castile, Sean Bell) the sense of this artist having lived with them can be overwhelming. These paintings come across less as portraiture than magical communion based on the artist’s interaction with the idea of his dead subjects. We may never know them so well.

Henry Taylor, Gettin it Done, 2016. Hudgins Family Collection, New York. Image and work © Henry Taylor. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

About a quarter of the exhibition was made specifically for the show. Among the 152 pieces in “B Side,” my favorites are paintings (mostly portraits) that come across like funk-filled story-songs. But nothing in these MOCA rooms has more arch autobiography baked in than the untitled typewriter case, except maybe the neighboring art objects (displayed together in a vitrine) comprising painted objects such as cigarette packages and cereal boxes—the default products of the artist’s inability to afford proper canvases early in his career. He smoked Newports and ate Lucky Charms, and—at least one time, presumably—used the similar budget typewriter to the one that I struggled to get my stories across with.

Mistaking a Black person’s effort to be correct for aspirational whiteness is an especially American phenomenon. One need not have read The 1619 Project to be in on the artist’s joke—the distinction that Taylor’s creation makes is in broad conversation with Black America.

Though his works rely heavily on a reporter’s eye, gut and experience say that Henry Taylor would not have meshed well over on First Street, in the Times building. The painted type writer case, created not so very long ago (2021), at my center of this vivid exhibition, tells all the stories that a commercial painter’s child from Ventura would in time get more than right.