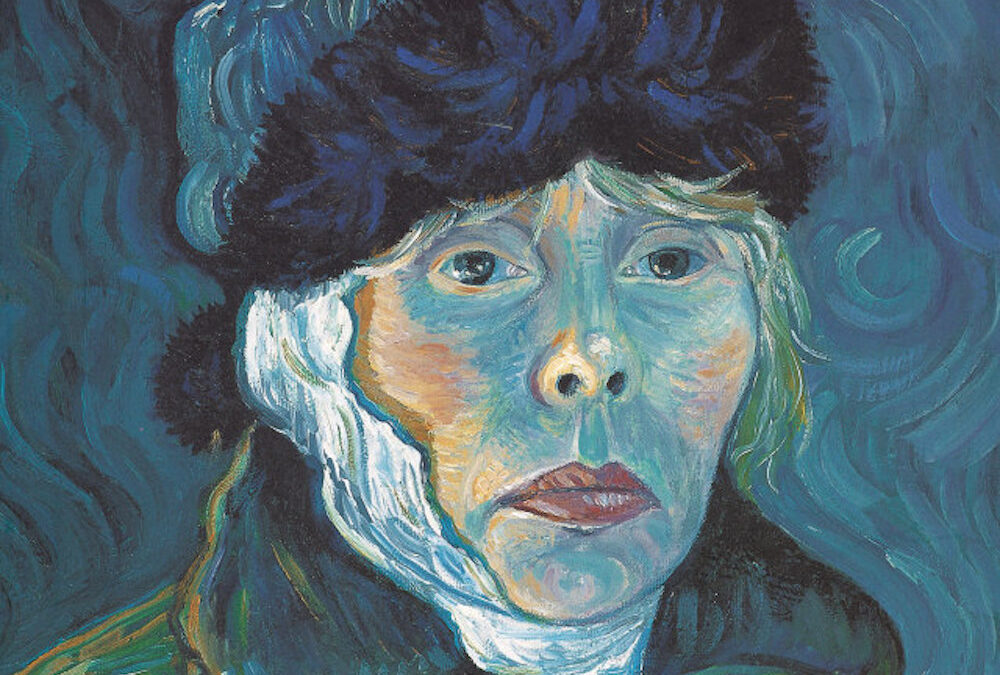

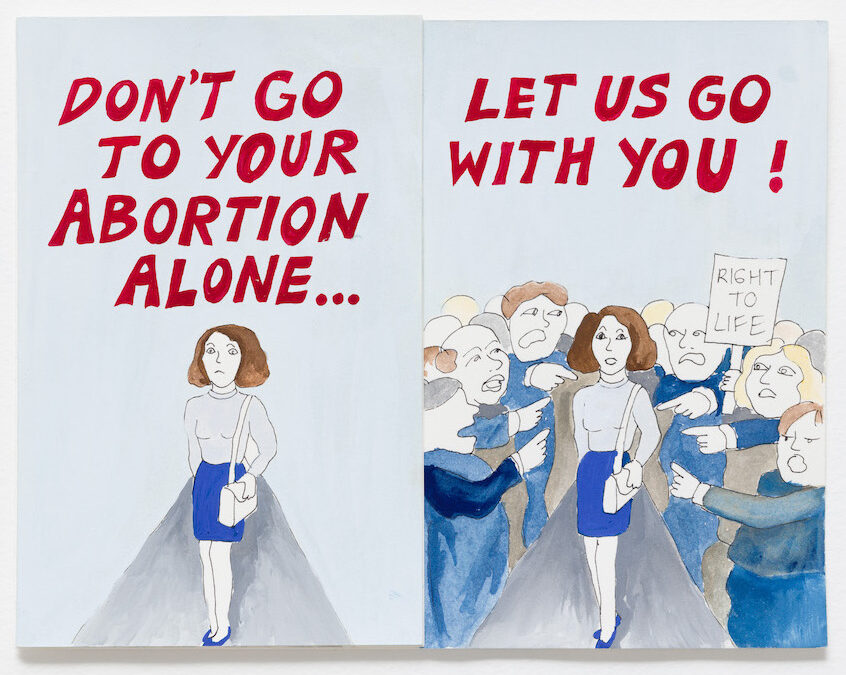

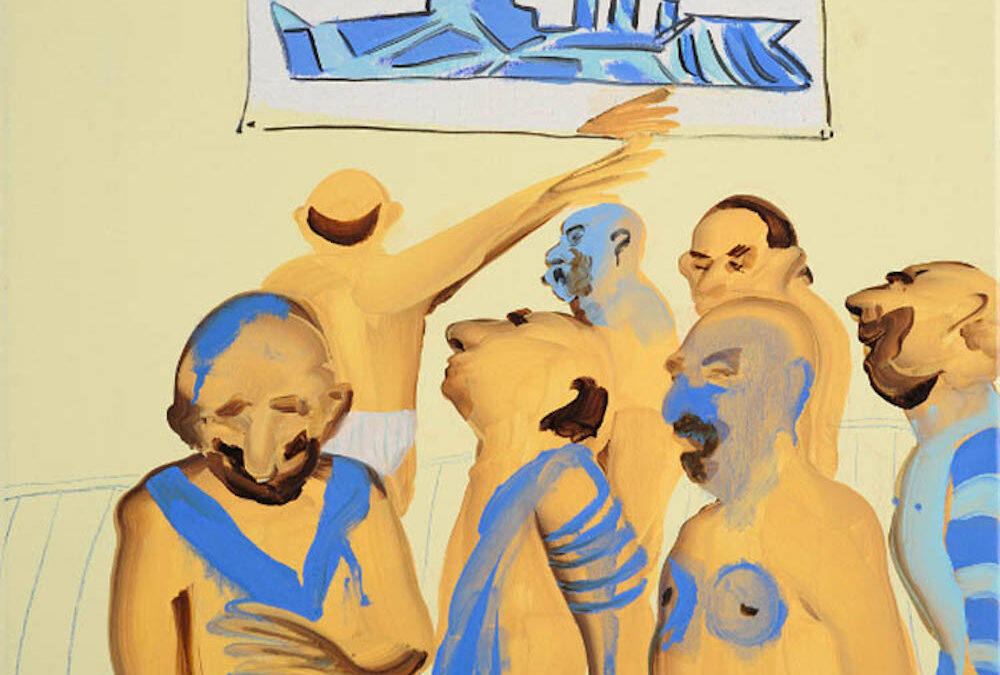

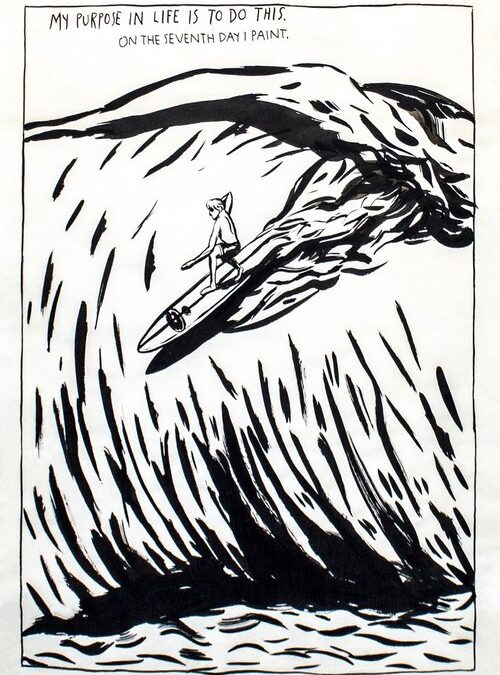

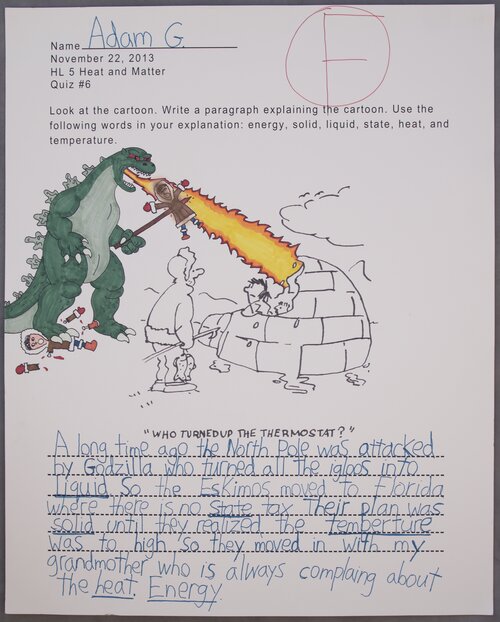

Thrift stores are potentially the end of the line for any object on sale therein; after that, it’s either ref-use or reuse. Consequently, there’s a poignancy to the purchase of any artwork from a thrift store, whether by an ironic hipster being or a sincere abuelita....