I have a friend who, for the most part, paints abstract paintings. We were talking on the couch the other week about this period where she had started making not-abstract paintings. She had painted paintings with images of recognizable things, with words, with clear references to the issues of the day. “I wanted to do what I wasn’t supposed to do,” she said.

This struck me as new and odd—or, at least, counter to my experience and understanding. The contemporary art world I knew—the one I’d been told about since at least high school—very much craved messages and clear references to the issues of the day. Not only do artists whose work refers to topical lefty issues occupy an esteemed position in the layer cake of art-critical discourse, but even artists whose work’s connection to topical lefty issues are less than obvious, are obscure, or are arguably nonexistent, are described and promoted using the language of topical lefty discourse. If you believe what you read, contemporary sculptors, painters, video artists and installation installers are forever shaking up status quos, forcing us to question received ideas, critiquing commercial culture, and promoting diversities and alternatives.

At least within the relatively cloistered hothouse of the contemporary art world, my understanding is that what we were all casually expected to do is (while steering clear of becoming the kind of confrontational career-suicide who forces art-support institutions to confront the not-lefty-friendly parts of their power base) pretty much constantly tackle topical lefty topics in a way that would align us with the New Yorker or NPR view of the world, thus making it all the easier to get written up in the New Yorker or interviewed on NPR and so remain relevant. That’s what every single well-known artist in living memory had done before.

However, my friend reminded me that this top layer of the art cake—occupied by artists who casually say things like “my next retrospective”—is not the only layer with enough icing on it to put your kids through college. Many mind-bendingly good artists occupy a low or mid-tier strata where the job is less about the art speaking to writers who in turn speak to potential customers, but more just the art dealer talking straight to the customers. And sometimes what these absolutely commercially necessary customers want is: to put the painting in a bank, or a hotel, or some other place where a Republican, a small child, or an unusually Catholic person might see it.

These may seem like strange places to put contemporary art, but there are a lot of them.

In many ways it is not even a question of offense. There’s a certain quality to images that make their plays for your attention on very specific terms—on my way to the drugstore I will notice images asking me to buy a beer, to watch a television show, to support a candidate and/or a cause, to change lanes, to beware of dogs, to use the other door, to press the button to call the clerk. None of these are bold creative or social statements but they all ask something super-specific of me, and they all dissolve into visual noise once the asking has been addressed: I already watch that show, I did change lanes, I voted for the other guy. Art with this quality—the quality of asking, by implication, for a judgment or a take on some other thing in the real world, the quality that nearly any representational image has—there’s always a risk that it annoys someone, that it’s a little louder on the wall than a big lavender lozenge, no matter how lovely. This can make it harder to sell.

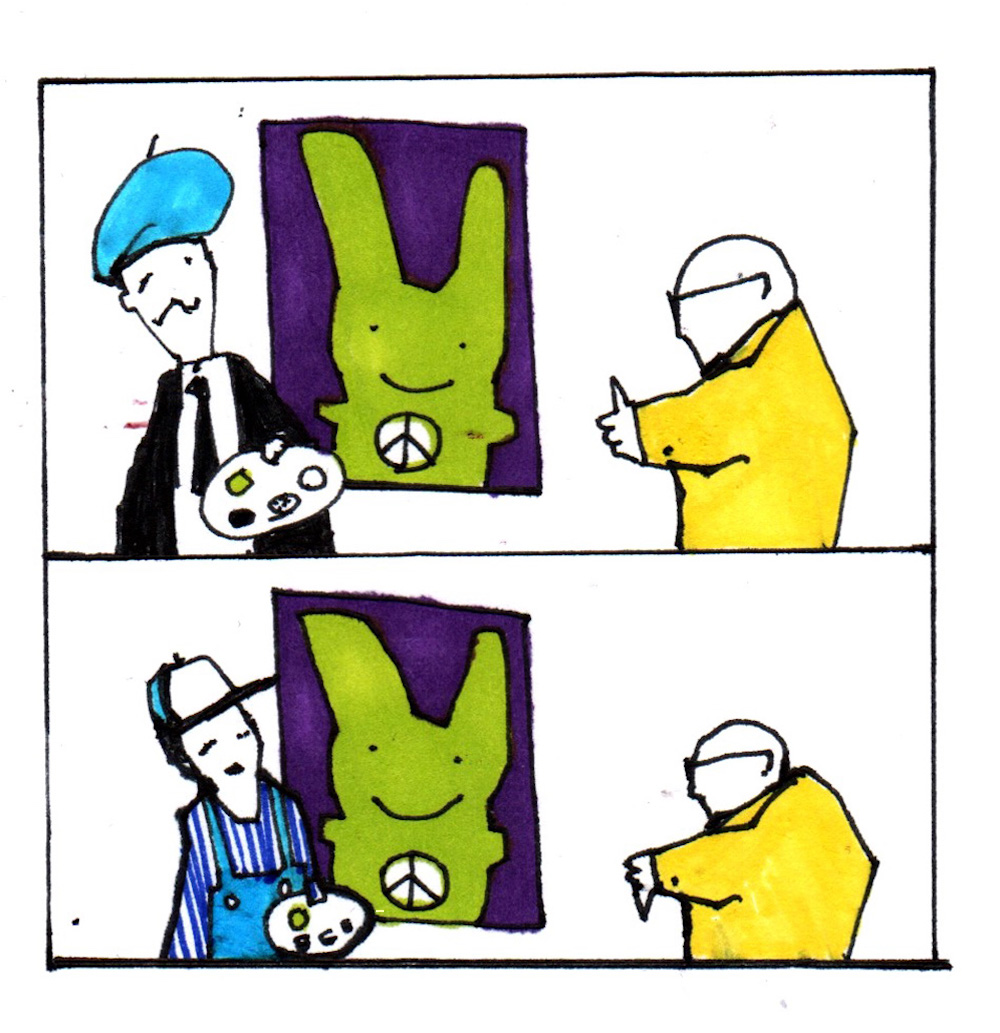

What emerges is a bizarre class system of expression: artists who have a bulletproof sniper’s nest (like having escaped a prison camp or having gotten famous in the ’90s) out of which to spray their bullets have the ability to make art full of statements and can be sure this statement-making is received as heroic, and they can sell work off that reputation so long as it can be distinguished from those lower down in the pecking order who—while having views that are nearly identical—are less phenomena of the media than of the luxury goods business. These artists must ride to work on the same squeamish tides of commercial demand as any other product in the market and might be punished not so much for rocking the boat as for reminding the sailors the sea has waves.

Sometimes they want you to say something and sometimes they don’t, but the boldest statement—the one that involves risking something real that you might not get back—is not caring

0 Comments