“The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned….” W. B. Yeats, The Second Coming

Since its inception, Pussy Riot (Nadya Tolokonnikova, Maria Alyokhina, Yekaterina Samutsevich, et al.) made the balaclava a trademark, but I couldn’t help being reminded Friday night—at the demonstration-vernissage-performance of Nadya’s Pussy Riot Putin’s Ashes show at Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles—that it also served an entirely utilitarian purpose as an essential mask or camouflage. Even at the time of their 2012 performance at Moscow’s Church of the Redeemer, it was almost inevitable that, given the Russian Orthodox Patriarch’s (Vladimir Mikhailovich ‘Kirill’ Gundyayev) well-established connections with Kremlin leadership and Vladimir Putin in particular, pressure would be exerted to detain or arrest them; and within a week of their performance, they were.

Their arrest was met with immediate protest in Red Square and beyond, but they remained under arrest, were charged and ultimately tried. Few in the Moscow art world at the time expected more than a wrist-slap level penalty; Tolokonnikova was already well-known, in part through her connections with the protest art collective, Voina—which only the year before had been awarded a state-sponsored(!) prize for their protest art (including a performance explicitly flipping off the FSB—successor to the KGB, Putin’s first employer). But as Americans have learned over the last year or so (Britney Griner), the Russian legal system (if you can call it that, given built-in prosecutorial bias, its judicial caprice and heavy-handed enforcement of state authority), has a way of escalating the wrist-slap to the draconian-punitive.

Tolokonnikova is free, in Los Angeles, and continuing to raise her voice against the world’s most powerful mass-murdering chief of state; but beyond her appearance Friday night, her whereabouts can only be identified to the extent geo-location tools may place her coordinates from one moment to the next. Putin may or may not (at least not immediately) be headed for history’s ash-heap, but his foes are never out of his sightlines. His surrogates and operatives are everywhere; and his identified opponents—or even self-exiled one-time allies—have been dropping dead just about everywhere under predictably dubious circumstances.

But we all felt vulnerable Friday night. Surveillance footage of the Pelosi assault in the morning. Memphis police monitoring camera footage at dusk. Many of us came to what felt more like a vigil than a performance, having just viewed yet another black man tortured to death in broken but unedited video sequences with real-time impact. (Emmett Till died for what exactly? Were Inquisition tortures ever this bad? Afghanistan and Iraqi atrocities? Guantanamo??) The many balaclavas we donned felt as much a concealment and admission of vulnerability as a signifier of willful, inexorable resistance to oppression. No point to ‘putting on a brave face’—although I could see that many of the unmasked in the audience were trying. We were still in shock.

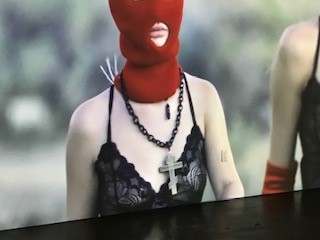

The performance that became Putin’s Ashes appeared to have been shot in the desert. A cohort of 12 young women appear to come over a rise descending onto a gray landscape of scraggly brush, gravel and dessicated foliage. The performance gets down to its business briskly—essentially an execution and cremation in effigy. But here again, as Tolokonnikova and her fellow performers had in 2012, the performance had a quasi-religious frame. They rapidly paired off, bearing their ‘icons’ and ‘instruments’ as they might in a religious procession; the trappings of choir (or conceivably judicial) ceremony swapped out for black slips, fishnet stockings, and long red gloves, with red balaclavas their executioners’ hoods. Hard not to think that in a lighter, more hopeful moment (conceivably only a year or two before their fateful Moscow performance), such a performance might be played to almost comical effect. But their white-hooded leader (Nadya)—in more conventional black-and-white ‘schoolgirl’ attire—raised her dagger and made plain their court’s intention to deliver damning and deadly judgment.

The performance that became Putin’s Ashes appeared to have been shot in the desert. A cohort of 12 young women appear to come over a rise descending onto a gray landscape of scraggly brush, gravel and dessicated foliage. The performance gets down to its business briskly—essentially an execution and cremation in effigy. But here again, as Tolokonnikova and her fellow performers had in 2012, the performance had a quasi-religious frame. They rapidly paired off, bearing their ‘icons’ and ‘instruments’ as they might in a religious procession; the trappings of choir (or conceivably judicial) ceremony swapped out for black slips, fishnet stockings, and long red gloves, with red balaclavas their executioners’ hoods. Hard not to think that in a lighter, more hopeful moment (conceivably only a year or two before their fateful Moscow performance), such a performance might be played to almost comical effect. But their white-hooded leader (Nadya)—in more conventional black-and-white ‘schoolgirl’ attire—raised her dagger and made plain their court’s intention to deliver damning and deadly judgment.

The perforated billboard icon of Putin echoed the half-tone newsprint image that might effectively serve as a visual equivalent for his own reality—isolated behind a bulletproof Kremlin security apparatus and insulated by a cadre of yes-men from the grim actualities of his war, terror apparatus, and the deterioration of daily life in his own country. This is a fire of his own making and Pussy Riot have simply delivered him to his fate.

The perforated billboard icon of Putin echoed the half-tone newsprint image that might effectively serve as a visual equivalent for his own reality—isolated behind a bulletproof Kremlin security apparatus and insulated by a cadre of yes-men from the grim actualities of his war, terror apparatus, and the deterioration of daily life in his own country. This is a fire of his own making and Pussy Riot have simply delivered him to his fate.

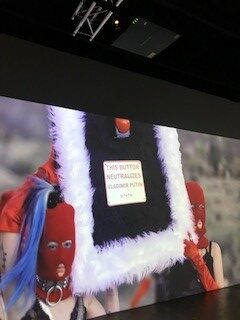

But notwithstanding the focus on Putin, the visual cues had an aspirational dimension. The framed red ‘button’—shorthand for the infamous nuclear arms command ‘football’—poised to “neutralize” Vladimir Putin under Tolokonnikova’s hand, might also “eliminate(s) sexism” (framed as with the performance button, and installed in its own space on another level of the gallery). I think this might have been better expressed as ‘eliminate’ or ‘neutralize the patriarchy’. But the intent was clear enough.

But notwithstanding the focus on Putin, the visual cues had an aspirational dimension. The framed red ‘button’—shorthand for the infamous nuclear arms command ‘football’—poised to “neutralize” Vladimir Putin under Tolokonnikova’s hand, might also “eliminate(s) sexism” (framed as with the performance button, and installed in its own space on another level of the gallery). I think this might have been better expressed as ‘eliminate’ or ‘neutralize the patriarchy’. But the intent was clear enough.

It was also noteworthy that this Pussy Riot cohort—not coincidentally the size of a jury—all wore the Russian Orthodox cross—an explicit rebuke to both Putin and his ally, the Patriarch of Moscow, but also appropriation of a symbol of patriarchal authority to its own ends: letting the patriarchy fall by its own standard, and neutralizing its cultural authority. There is the half of humanity that may be ‘redeemed, and the other half (the downward slant of the ‘footrest’ bar) condemned to hell. (Arguably that incline should be a lot steeper, but the point is made.)

It was also noteworthy that this Pussy Riot cohort—not coincidentally the size of a jury—all wore the Russian Orthodox cross—an explicit rebuke to both Putin and his ally, the Patriarch of Moscow, but also appropriation of a symbol of patriarchal authority to its own ends: letting the patriarchy fall by its own standard, and neutralizing its cultural authority. There is the half of humanity that may be ‘redeemed, and the other half (the downward slant of the ‘footrest’ bar) condemned to hell. (Arguably that incline should be a lot steeper, but the point is made.)

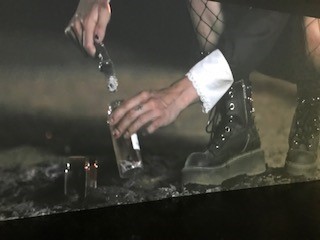

The flames reduce the image to ashes, which Tolokonnikova than retrieves to be placed in slender vials (also part of the installation). The symbolism of portioning out Putin’s ‘ashes’ into 100 mg, 30 mg, and 5 mg vials wasn’t clear to me. The point of their toxicity seemed to have already been well established. But again, the appropriation of religious rites and symbolism were very much a part of the performance and exhibition.

The flames reduce the image to ashes, which Tolokonnikova than retrieves to be placed in slender vials (also part of the installation). The symbolism of portioning out Putin’s ‘ashes’ into 100 mg, 30 mg, and 5 mg vials wasn’t clear to me. The point of their toxicity seemed to have already been well established. But again, the appropriation of religious rites and symbolism were very much a part of the performance and exhibition.

They can’t kill us all, we think; and—absent a nuclear blast—they can’t. But as the news out of Ukraine reminds us every single day, they can kill a lot of us. And why stop with hostile foreign agents when too many of us are subject to the random terror of police assault under color of law.

From Washington to Florida to Texas to Arizona, authoritarian-minded political operatives continue to organize from the legislatures to the streets to turn the country away from its sister democratic states and make the U.S. over into a police state. And there’s clearly no shortage of thugs—of every religion, race and ethnicity—to help them do it.

Except that we’re not martyrs. (Writing this as I’m listening to a Met broadcast of Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites—where in the penultimate scene, the soon-to-be disbanded sisters offer themselves up not to their religious order, but to martyrdom—and the irony is screaming at me not unlike the Prioress, Mme. de Croissy, on her deathbed. ‘Hey—Goddesses—this isn’t what I had in mind!’) The culture does not belong to the patriarchs, however riddled it may be with their toxins. They can hold on to their arsenals. We’re donning not veils, but balaclavas; and we won’t be going quietly.

Except that we’re not martyrs. (Writing this as I’m listening to a Met broadcast of Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites—where in the penultimate scene, the soon-to-be disbanded sisters offer themselves up not to their religious order, but to martyrdom—and the irony is screaming at me not unlike the Prioress, Mme. de Croissy, on her deathbed. ‘Hey—Goddesses—this isn’t what I had in mind!’) The culture does not belong to the patriarchs, however riddled it may be with their toxins. They can hold on to their arsenals. We’re donning not veils, but balaclavas; and we won’t be going quietly.

0 Comments