Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Doug Harvey

-

UNDER THE RADAR: TEMPORARY SERVICES

About a month ago Virginia Katz cajoled me into leading a discussion at her regular public salon at Eastside International gallery at LA’s Brewery art complex. Since every time an art critic speaks in public an angel loses its wings, I am not really big on the whole oral thing. But I have this manifesto I’m working on? And I wanted to run some ideas up the flagpole. So my topic was “Can the Art World be Reformed or Should We Just Move 5 Miles to the Left and Start from Scratch?”

The consensus seemed to be that if TAW (The Art World) was to suddenly shift its resources to support the people in that particular room, then: problem? What problem? No problem! Which I totally agree with; but I’m not holding my breath. Though I got a lot of good feedback for my coming Manifesto, you can probably guess that I lean more toward the “5 Miles to the Left” scenario. I was about to reveal my 5-year 5-Point Plan, but I was waiting for Carol Cheh to return from her smoking break. I waited and waited. Whatever happens next Carol, it’s on you.

One of the key phrases that I forgot to mention in my topic was “Or has it already happened?” One of the most promising signs of that possibility arrived in my mailbox a couple of weeks later. Alongside a passel of recent publications (we’ll get to that) there was this… manifesto of sorts:

We strive to build an art and publishing practice that:

- Makes the distinction between art and other forms

of creativity irrelevant - Builds and depends upon mutually supportive

relationships - Tests ideas without waiting for permission

or invitation - Champions the work of those who are frequently

excluded, under-recognized, marginal,

noncommercial, experimental, and/or socially

and politically provocative - Puts money and cultural capital back into the work

of other artists and self-publishers - Makes opportunities from large museums and

institutions more inclusive by bringing lesser-known

artists in through collaborations or advocacy. - Insists that artists who achieve success devote

more time and energy to creating supportive social

and economic infrastructures for others

I’m not sure about the whole making “opportunities from large museums and institutions” dealie, but I trust these guys.

I first heard about Temporary Services when—under the aegis of the Outpost for Contemporary Art—they occupied a vacant lot at the corner of Sunset and Alvarado in 2005, building a proto-selfie-museum from shopping carts, perfectly good headboards and other curbside scavengings; holding potlucks, DJ sets, urban foraging workshops, film-screenings, and giveaways of their zines. At that point their publishing output must have been around 60-something titles, and their most recent items left a big impression: Framing the Artists—an extensive, incisive and deadpan compendium of depictions of artists and art in movies and TV; Public Phenomena: Informal Modifications of Shared Spaces—the second in an ongoing series compiling documentation of homemade basketball hoops, parking space savers, roadside memorials and other vernacular art and engineering projects; and a poster iteration of what is possibly still their most famous anthropological study, Prisoners’ Inventions, a simultaneous celebration of human ingenuity and indictment of the prison-industrial complex. (All of these are out of print but available as free PDF downloads at temporaryservices.org).

And this is just the tip of the iceberg. While TS maintained their activities as situationist provocateurs with a variety of workshops, happenings and institutional interventions, by 2008 it became obvious that their pamphlets, posters, books and zines were their most effective tools for networking and disseminating ideas. So they formed a publishing imprint and online store called Half Letter Press to consolidate and monetize their own projects, and to expand their collaborative capacities—they’re in bed with local zanies The Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, and a couple of dozen kindred fringe-dwelling small presses, including PRINTtEXT, whose hot-off-the-Risograph Brush Master examines the legacy and impact of that Indianapolis hand-painted signmaker.

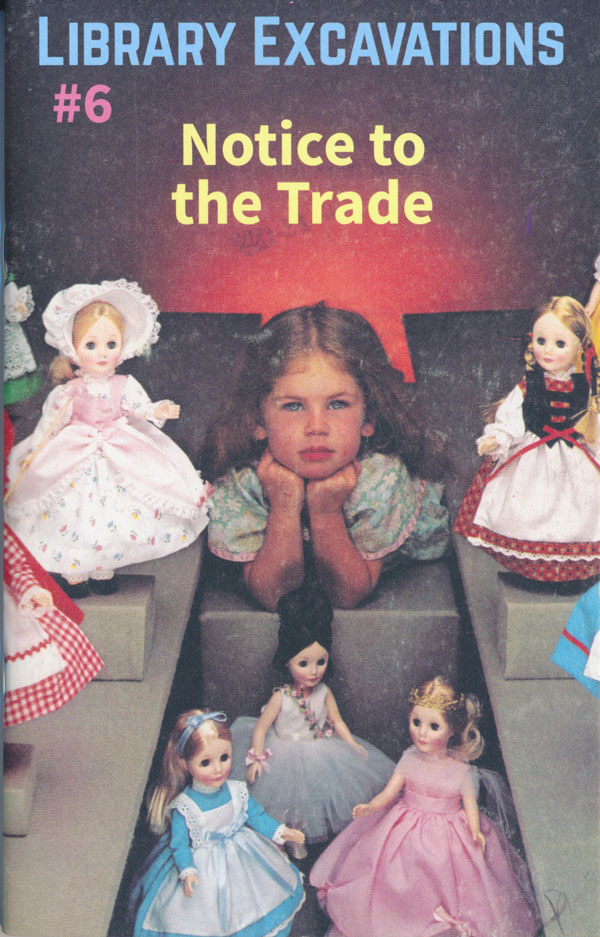

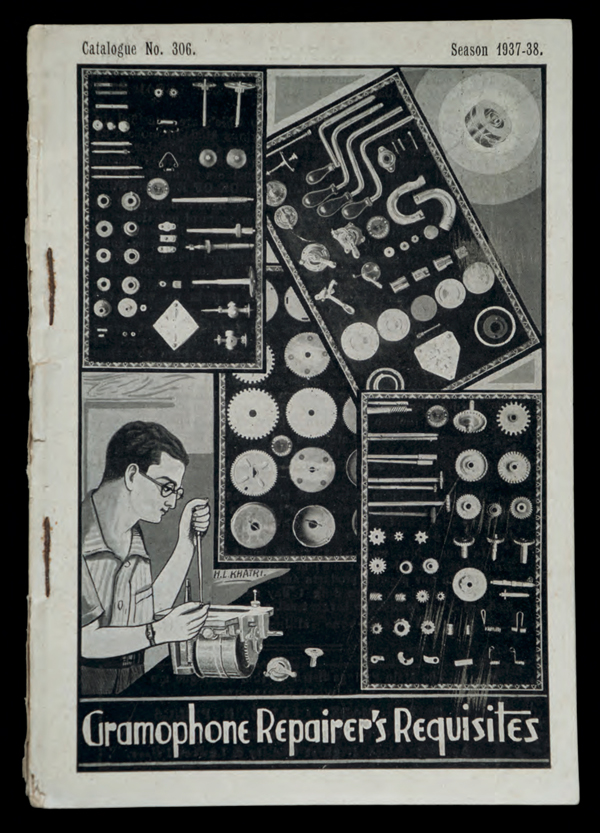

Zine covers from Temporary Services and Half Letter Press. Still, it’s the output of founding TS members Brett Bloom and Marc Fischer that most consistently poke at the wound in Art’s side—their recent collection of photographs of Abandoned Signs taps into a vast field of entropic semiotics that is of tremendous importance, as are the patacritical archive explorations Fischer conducts under the sobriquet “Public Collectors.” These include Hardcore Architecture—a series collating contact listings from ’80s hardcore networking bible Maximum RocknRoll with Google Street View images of the corresponding dwelling; MATALICA TICKETS, a found avant-garde literary text made from the keywords from a single Craigslist ad for the titular commodity; and the seemingly inexhaustible Library Excavations series, which shifts its focus from decommissioned VHS tapes to the art used to illustrate art-therapy manuals to specialized cease-and-desist ads from toy trade journals— “Warning! Care Bears™ are a Protected Species!”

While I love the Library Excavations, it would be quite easy to slip into a neo-Medieval hermeticism, hiding in the alcoves, scanning, pasting up, Xeroxing, and shipping out your discoveries. That’s one of the conundrums of publishing as a means to moving 5 miles to the left and starting from scratch—how can you be sure there’s anybody listening? But I guess I am, and if you made it this far, you are. And with Brett and Marc that makes four—good enough! Let the Revolution begin! Manifesto coming soon.

Zine covers from Temporary Services and Half Letter Press. temporaryservices.org; halfletterpress.com

- Makes the distinction between art and other forms

-

FILM: Wild Wild Country

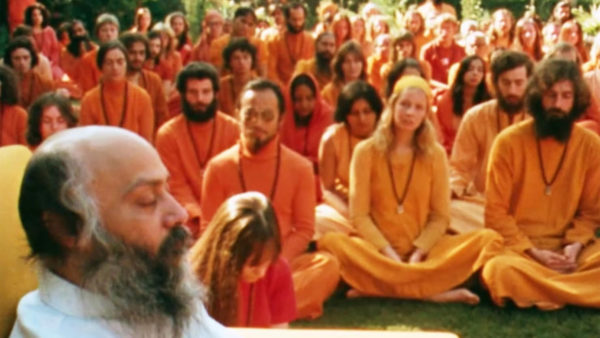

When I initially started hearing the buzz surrounding filmmaker brothers Chapman and Maclain Way’s Netflix documentary series about the Indian guru Bhagwan Rajneesh’s failed attempt to establish a large commune in rural Oregon in the 1980s, I was surprised—hasn’t this story been rehashed a million times? As I began to learn more, I was startled that many commentators, reviewers, my own friends and the filmmakers themselves claimed to have been previously ignorant of the story. A story which, at the time, generated one of the most frenzied media circuses ever surrounding the issues of so-called “cults” and religious freedom in America.

The saga of the city of Rajneeshpuram was seen by many of those connected to the “Human Potential Movement”—the grab-bag of psychological, sociological and spiritual experiments that emerged in the wake of the psychedelic ’60s—as the death knell of the commune phenomenon, and the climax of a deliberate decades-long campaign to delegitimize, destabilize and disempower these politically autonomous experiments in intentional community-building. The success of this strategy can be measured by the cultural amnesia that gives the Ways’ Wild Wild Country its frisson of novelty, and by the default cartoonishness the resulting documentary—as fair and balanced as it tries to be—uses to depict the conflict and its players.

The nutshell spoiler-lite version—and I definitely recommend watching the series, in spite of my misgivings—goes something like this: In 1981, the nonprofit Rajneesh Foundation bought a 64,000-acre ranch in rural Oregon, and immediately began to transform the rugged wilderness into a functional city—eventually including housing for 7,000 people, restaurants, shopping malls, giant meeting halls, a 4,200-foot airstrip, a dam and reservoir, sewage and electrical infrastructure, a public bus system, postal system and fire and police departments. Locals were not amused. Antics ensued, including salad-bar bioterrorism, assassination attempts, election and immigration fraud, and the defection of the Rajneesh’s zany right-hand iron lady, Ma Anand Sheela.

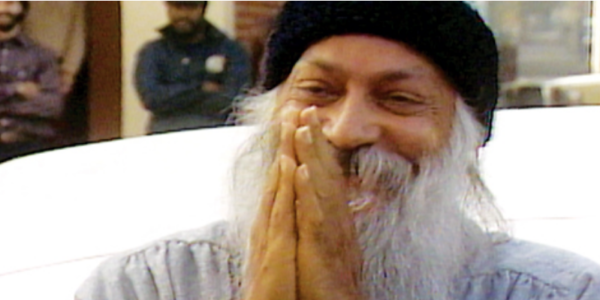

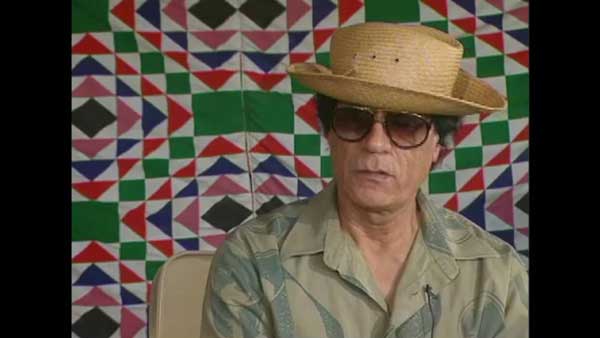

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh was already a famous and wealthy spiritual leader when he moved his center of operations to the U.S. Unusual for his broadly syncretic approach to spiritual offerings—incorporating Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist, Christian, Hassidic and Sufi teachings in his system alongside Gurdjieffian exercises and Gestalt psychotherapy— he attracted a massive following of highly educated Westerners, drawn to his anti-authoritarian tone, irreverent humor and emphasis on sexual freedom. “Religion,” he said, “is an art that shows how to enjoy life.”

Almost none of this—apart from the sexual freedom part, of course—makes it into the six hours of old and new footage (brilliantly edited by Neil Meiklejohn into a suspenseful marathon of credibility ping-pong) that make up Wild Wild Country—nor is there any but the most cursory explanation of what exactly the residents of the commune did when they weren’t donating their construction labor or lining up for Rajneesh’s daily Rolls-Royce drive-by blessing. But the viewer comes away with no sense of why anyone would devote their entire life to such a conspicuously unconventional lifestyle, apart from some vague speculations that “everyone wants to feel like they belong.” But Mr. Rogers Neighborhood this ain’t!

This heavy bias towards character-driven, sensationalistic storytelling seems naive; the outcome most certainly disingenuous. I find it hard to believe that Hollywood insiders like the Ways—nephews of Kurt Russell whose only other film was a documentary about their grandfather Bing Russell’s Indie Portland baseball team, the Mavericks—could have never heard about Rajneeshpuram. The implication that the project was inspired by the discovery of a forgotten treasure trove of archival news footage is belied by the perfectly serviceable 2012 Oregon PBS documentary Rashneeshpuram (available for free viewing online at www.opb.org/television/programs/oregonexperience/segment/rajneeshpuram/) which shares many of WWC’s most arresting clips.

But hey, that’s showbiz, right? The creepier thing for me is the filmmakers’ apparent obliviousness regarding the motivation and techniques of thousands of people—millions if you include all the other communal experiments—whose attempts to deprogram themselves and each other from the cult of mainstream consumer materialism were first crushed by bureaucratic and paramilitary coercion, then erased from an official history that only grudgingly acknowledges the Civil Rights Movement, while burying most of the enormous social upheavals of the last century under an avalanche of entertainment trivia. The crazy sex guru and his gun-toting, salad-bar poisoning minions who duped rich hippies into buying him 93 Rolls-Royces, then tried to take over a god-fearing frontier town, is undeniably TV-documentary gold, but lurking beneath that there’s a far more dangerous and exciting story to be told. Hey, that rhymes!

What is art? Can it be the carving of a negative social sculptural space out of the undifferentiated Matrix of late capitalist cultural larb? Can it be the operatic socio-political-spiritual convolutions that ensue? Can it be a blithely propagandistic film documenting the historical moment through an epistemological filter of celebrity gossip? Can it be all of the above? I may know the answers but I can not tell you. You must find the answers for yourself. Start the Journey. It will change your life.

-

UNDER THE RADAR

I have a confession to make: I am Miroslav Kyropnik! (crickets) One of my sub rosa projects at UCLA was the creation of a body of work by a totally fictional outsider artist who took found photographs, magazine illustrations, and art reproductions and added speech balloons praising himself to the heavens. I then dropped the results into thrift stores and awaited their discovery and—depending on the response—either my big reveal or discovery of a trove of unsuspected Kyropnik originals. Still waiting …

What brought this to mind was Brett Ingram’s recently published monographic volume The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler. Purporting to show the previously unsuspected outsider magnum opus of an aged (now departed) scientific illustrator at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, TSWoRK, made me suspicious right off the bat—mostly because Kuhler was just too perfect.

According to the official backstory, Ingram—a former space shuttle engineer turned multimedia artist/consultant—first ran into Kuhler on a bus in Raleigh. A tall and garrulous figure, Kuhler sported a white beard and ponytail, and was wearing a bizarre handmade uniform with brass buttons, epaulets, short pants and a Boy-Scout style neckerchief. He delivered a loud stream-of-consciousness monologue before disembarking a couple of stops before Ingram’s, leaving an indelible impression.

A couple of years later, Ingram got a gig at the museum and lo and behold, behind door #2, and the rest is history. Gradually opening up about his elaborate imaginary society— Rocaterrania, a small splinter country in upstate New York founded by Eastern European immigrants who couldn’t abide the concept of democracy—Kuhler seemed to be the ideal outsider artist—eccentric, erudite, high-functioning, photogenic; yet responsible for a private universe as detailed and idiosyncratic (almost) as Henry Darger’s outsider nations of Glandelinia and Abbieannia.

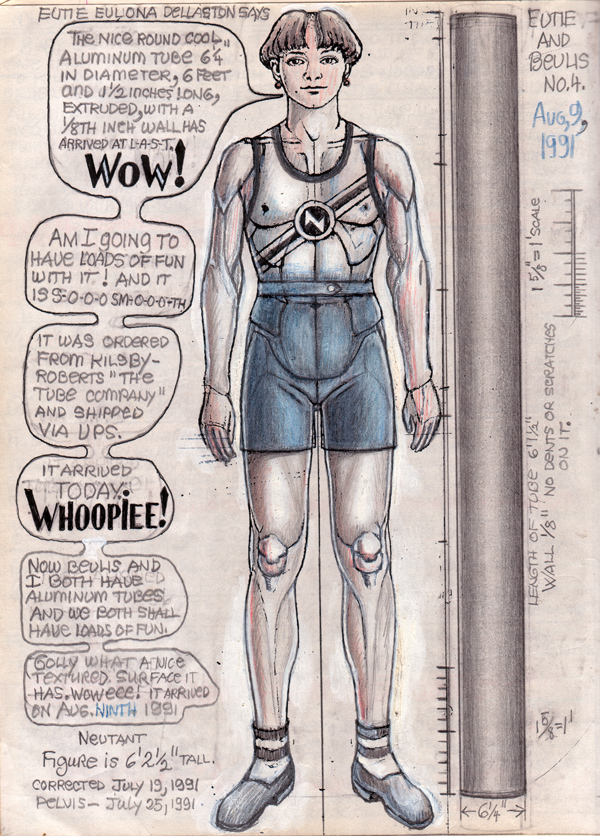

Conceived in 1948, when Kuhler was a miserable precocious teenager stuck on a ranch in Colorado, Rocaterrania evolved over the next 60 years, reflecting the practical challenges and psychological struggles in the artist’s life through convoluted genealogies, historical intrigues, urban renewal, propaganda, linguistic experiments, and sci-fi–tinged social engineering—particularly cruel Empress Catherine’s wide-scale neutering of orphaned children and juvenile delinquents to create a class of “Neutants.”

All of this was copiously illustrated in a range of graphic styles, primarily pen-and-ink crosshatching and stippling with an old engraving type vibe, which strangely, over time, began to resemble the work of underground cartoonists—R. Crumb, Kim Deitch and Jim Woodring all come to mind. Kuhler’s elaborate calligraphy—a mutated Cyrillic font—rivals the exquisite psychedelic penmanship of Rick Griffin.

Kuhler also worked in colored pencil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and mixed media, as well as fashioning baroque smoking pipes out of bric-a-brac, various models (including a life-size mannequin of his neutant surrogate Peekle Hannaford). He filled scrapbooks, diaries and sketchbooks, and had dozens of versions of that crazy uniform—for the Rocaterranian National Labor Service.

Another red flag is the way the book is structured. There’s a brief intro with details of his early bio—born in Jersey to a famous German train designer and an icy Belgian mama, moved to upstate New York, sent to boarding schools where he was bullied, uprooted to the ranch at age 16. After that, it’s pretty much a deadpan presentation of the history of Rocaterrania, as if Kuhler had decided to share his vision in a self-published academic tome, devoid of irony, interpretation or context. It’s all like “Here are the diagrams of the streetlamps lit by methane gas harvested from Rocaterranian poo (See fig 187)”—a brilliant editorial aesthetic decision, but suspect. Where were the Joseph Campbell quotes? The queer theory deconstruction?

I decided to call Ingram’s bluff and contacted him: “You made this all up didn’t you? That dude looks just like [LA collector] Stuart Spence.” I explained, “He’s already confessed to me,” I lied. “All charges will be dropped.”

“Made what up?” he responded via email, “Rocaterrania? Not a chance. I wish I were that imaginative! You’ll see when you get the movie. The term ‘true original’ is often overused, but Renaldo really was a nation unto himself.”

The movie in question is entitled Rocaterrania. Ingram sent me a copy, and he was right. The more traditional biographical documentary approach had already been done, and done right. Extensive interview footage of Kuhler himself show him as a remarkably self-aware artist, an adamant non-conformist, a deeply compassionate and ethical (dual) citizen, and an outrageous prima donna. The power of creativity to compensate for profound psychological trauma has rarely been more clearly demonstrated.

I must recommend that you purchase both the book and the DVD to get the story from both angles. And forget what I said about Miroslav Kyropnik. I was just pulling your leg. Wait until you see the movie. Now where did I leave Stuart Spence’s number …?

-

UNDER THE RADAR

This whole end-of-net-neutrality panic is a bit of a mystery to me. Sure, it sucks, but what were people expecting? That businessmen would suddenly do the right thing, because, like, information wants to be free? So did Frederick Douglass, but trickle-down economics isn’t what allowed him to become somebody who’s done an amazing job and is getting recognized more and more.

The web is addictive, and its marketing—back to the days of endless complimentary AOL trial periods and the NetZero revolution—always smacked of schoolyard pusher ethics. “C’mon kid, the first one’s free! Everybody’s doing it! You don’t want them to think you’re a square, do you? You’ll feel out of this world!”

Now, everybody’s hooked and everybody’s shocked—SHOCKED!—that MacDaddy Warbucks is jacking up the toll? I’m just surprised that it took this long. Happily—in advance of the imminent global wave of digi-junkies hurling their devices out the window and bellowing “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!”—a group of forward-thinking content providers have been rolling out their wares in a new medium that’s so crazy it just might work.

What these visionaries are doing is taking the feeds from their websites, blogs and social media accounts, using printers to generate hard copies in a standardized format on dried sheets of pulped artisanal plant fibers, then binding them into a presentation format that resembles a sort of analogue mono-textual tablet, equipped with tactile ergonomic interactive capabilities and subtly nuanced variations in user interface that shift considerable co-creative responsibility onto the player. They call it a “book.”

This strategy isn’t entirely new—pioneer internet meme Mr. Winkle was translated into a series of bestselling books and calendars by photographer Lara Jo Regen (Artillery’s Sight Unscene columnist) back in the early ’00s. The first actual web-sourced book purchase I made was Steve Caire’s 2005 The Joys of Engrish from the www.engrish.com repository of Asian ‘patacritical signage (and purveyor of the “I’m the national treasure and I hate noise” mousepad).

The high bar was set in 2012 by Richard Littler’s Discovering Scarfolk—a travel guide to the previously virtual northwestern English community locked in a degenerating feedback loop of ’70s public service graphic design, nightmarish social engineering and Orwellian doublespeak (at https://scarfolk.blogspot.com/). Modified or wholly invented sound effect LP covers, magazine covers, children’s games, mass-market paperbacks, T-shirts, didactic posters and TV advertisements coalesce into a surreal mashup of The Wicker Man and ham-fisted safety warning films—the book version places these already virtuosic mock-ups into an overarching vintage horror-novel narrative framework.

Apple Cabin supermarket circular, 2013–16 (Liartown, 2016) Although it doesn’t attempt to compete with Scarfolk on a grand conceptual scale, the newly-released Liartown: The First Four Years (Feral House) throws down hard in terms of layered satirical and absurdist modifications of vernacular visual cultural material, and comes out ahead in the LOL department. Which is actually saying a lot, given that the residents of Scarfolk are partial to “erotic decorative masonry” porn, rabies-themed bubblegum cards, and helpful posters reminding schoolchildren that “Not All Hypnotising Arachnoid Demons Are Friendly (If you think a demon might have laid eggs in your head without permission, tell your parents.)”

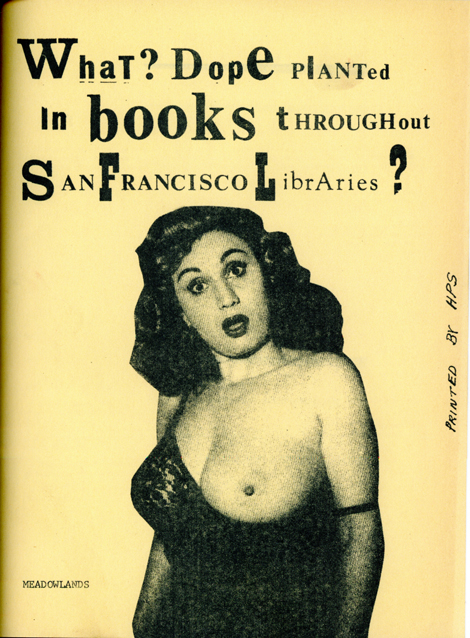

Rumanian Punishment Gifts by Etelka Penquelik, Craft magazine, 1980 (Liartown, 2015) Liartown doesn’t make any conscious effort to create a contextual fiction for its détournéed pop culture ephemera (although a certain parallel-universe consistency emerges) and that lack of focus opens up the playing field to include the entire gamut of visual culture from the last century and a half—credit cards, tattoos, fine art, VHS tape cases,16-month calendars, billboards, junk mail, key chains, Googie architecture, punk fliers, Civil War memorabilia, thrift store records, real estate signs, collectable dishware, postage stamps, aromatherapy candles and the summary screens that pop up when you pause a movie on Netflix. And that’s even before we get to the wide range of books, magazines and other printed matter that make up the bulk of Liartown’s satirical targets.

The humor is multivalent—frequently sophomoric (promo materials for the 1975 soft rock band Shitwind), outrageous (a “Tragedy Quilts” 2016 calendar featuring gorgeously rendered fabric abstractions of the WTC attack, the Challenger explosion, and Jackie Kennedy’s blood-spattered pink Chanel suit), cruel (a ’70 s nordic kid in some Sami-inspired sweater as cover boy for “Woolen Unfuckables”) or inexplicable (the Japanese interspecies workplace abuse handbook “Secret Touch of the Elk Boss!”)

Sean Tejaratchi, from Crap Hound #1/6: Death, Telephones & Scissors, 1994/2012 Liartown’s creator Sean Tejaratchi also seems enamored of John Cage’s famous dictum “If a joke isn’t funny the first time, tell it again and again and again until you get a MacArthur grant.” It worked in the ’90s when Tejaratchi applied it to mid-century clip art, compiling huge quantities of a narrow range of thematically sorted imagery into astounding horror vacuii compositions—without commentary—in one of the best zines ever published: Craphound. And it works in Liartown—although extra-strangely, mostly at the expense of wildlife.

Thus we find ourselves laughing at the mysterious celebrity career of Glen the Seagull without being able to remember what the joke, if any, was in the first place. None of this is meant as criticism—sophomorism, cruelty, outrageousness, inexplicability and maddening repetition are among my favorite aesthetic strategies. As is overwhelming semiotic bombardment, which brings us to anther level altogether.

Page from Crap Hound #5: Hands, Hearts & Eyes, 1996 Once the Nation Lampoon/zen koan literary impact of Tejaratchi’s send-ups have sunk in, you begin to notice the subtle complexity of his awareness and manipulation of a vast array of graphic design tropes. Half the humor of his “what-if” speculations—as in “What if there were an entire folk art niche dedicated to carved wooden bears holding signs that say ‘Fuck You’?”—would be lost if it wasn’t presented in the form of a typographically, compositionally dead-on rendition of, for example, the Woolburn Craft Library’s “Collecting Cussin’ Bears” 1987 price guide.

A sort-of moire-pattern of hilarity ensues from the contrast between the ridiculous implausibility of the message (“2014 Turd Wrestling Calendar”) with the immaculate mimicry of the medium. For visual artists, and others with observation skills attuned to the baroque intricacies of pictographic communication in mass media, the pleasures will be amplified exponentially. Other readers get it without even noticing—the more invisible the camouflage, the more surprising the punchline. But this “book learning” can start to take hold. Why not throw your iPhone down the garbage disposal and lock yourself in a dark room with Liartown? Once the robot monkey’s off your back you’ll emerge into a brave new world!

-

UNDER THE RADAR

Mimi Pond is a legendary figure in LA—part of the generation of independently-minded cartoonists nurtured—then dumped—by the alternative media, she also wrote the first-aired episode of The Simpsons (before being expelled from the bullpen) as well as contributing to Pee Wee’s Playhouse alongside her artist husband Wayne White.

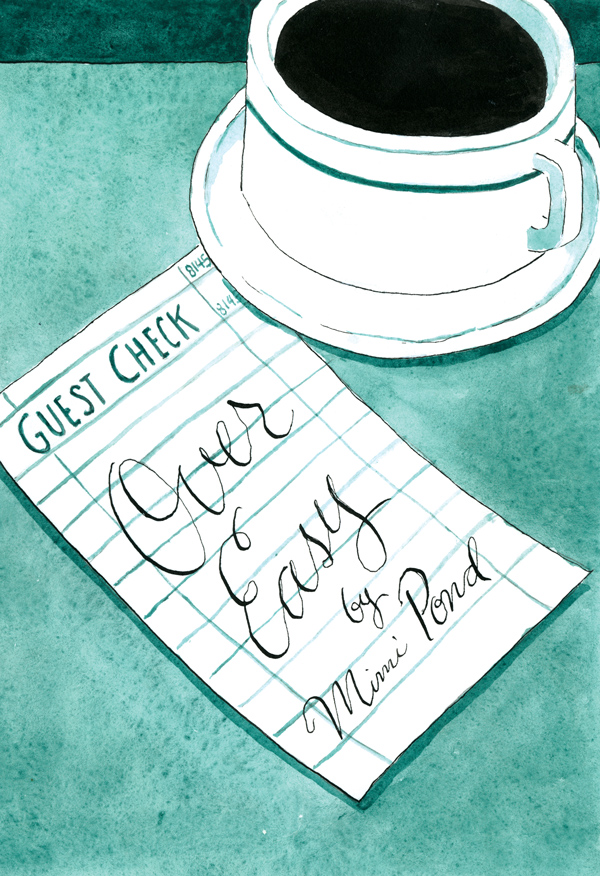

Pond’s public image has recently made a quantum leap in the shadow world of graphic novels, with her acclaimed 2014 fictionalized memoir Over Easy, which detailed her day-to-day social adventures after dropping out of the CCAC and getting a job as a dishwasher—soon waitress—at a nearly post-hippy diner in Oakland in the late ’70s.

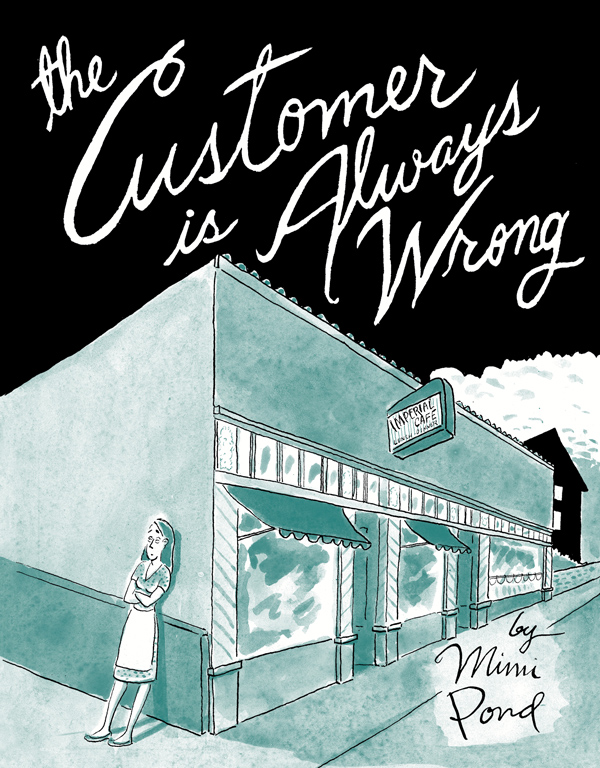

Her new volume, The Customer is Always Wrong, picks up exactly where Over Easy left off—vibrating between laid-back hippy self-mockery and seething punk rage. Although the saga of art-school dropout Madge and the colorful cast of Bay Area lowlifes with whom she consorts were apparently split into two for completely logistical reasons, the bifurcation is fortuitous.

The Customer is Always Wrong, cover Where the first volume chronicles a relatively idyllic period of compromised innocence—sex, drugs, and rock & roll in other words—the sequel delves into more challenging bardos, depicting beatings, murders, heroin ODs, and abortions with the same light attention as the awkward romances and naughty experimentation in Over Easy.

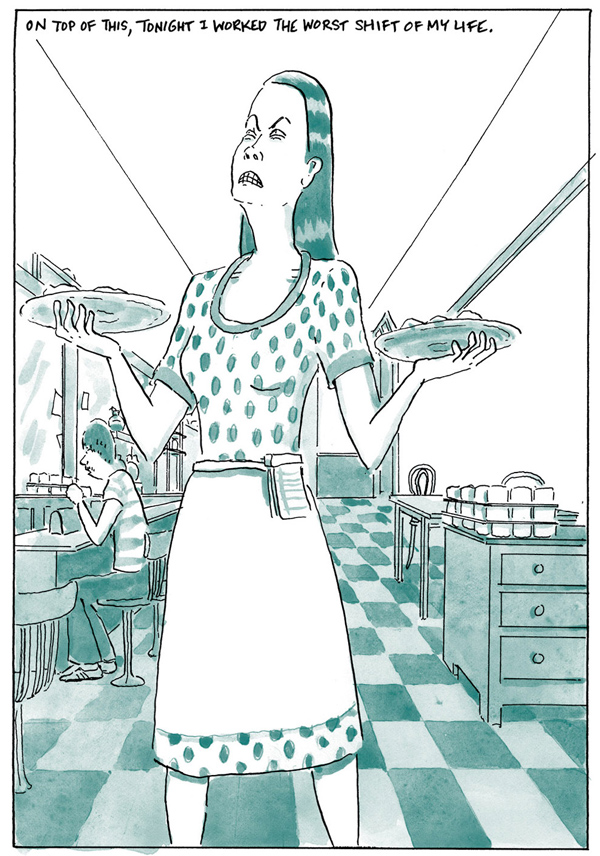

Pond’s lightness of touch is twofold, evident in both her artwork and narrative gifts. Her relaxed, economical black ink line—augmented by judiciously deployed washes of blue—conveys an archetypal bohemian vibe that immediately sets the tone for Madge’s subterranean journey, and is stylistically supple enough to accommodate anything from lyrical interludes to car-chase sequences.

The Customer is Always Wrong, p. 96 Her fondness for Edward Hopper—mentioned several times in the story—is evident in her carefully observed urban landscapes and architectural interiors, while her characters owe something to the deceptively loosey-goosey renderings of Roz Chast and the frenetically exaggerated body language of Lynda Barry’s Ernie Pook (though Pond’s official mentors were from her time at NatLampCo—Shary Flenniken of Trots and Bonnie fame, and the criminally under-recognized surrealist genius M.K. Brown).

Her writing is equally fluid, shifting from contemplative interiority to slapstick humor in the space of a few panels, focusing in for microscopic views of inner monologues, then pulling back to take in the bittersweet sociopolitical uncertainties of this particular time and place—ground zero of the ’60s counterculture at the point when it was staggering on its last legs.

Over Easy, cover Perhaps the strongest aspect of the story is its characterizations, building up a dozen or so complex central personalities with layers of nuanced observation, and sketching out twice as many with broad but incisive strokes. Lazlo, the manager of the Imperial Cafe, is the central figure of the narrative: a fun-loving, substance-friendly hepcat family man; a disgraced Latin scholar-cum-poet who glories in—and orchestrates—the absurdist chaos of the faltering utopian macrocosm surrounding him.

The narrative engine of the two-volume 700+ page epic is the gradual erosion of the tiny model anarchist society Lazlo has created from (and for) the various outcasts and misfits that populate the cafe, as his family life and other real world concerns increasingly intrude on his carefully crafted alternate universe.

Equally impressive is Pond’s quasi-self-portrait, which functions like a set of incrementally less judgmental nesting dolls—Madge the character is frequently exasperated by the coke-fueled antics of the greasy spoon brigade, while Madge the narrator has clearly learned (from Lazlo, it becomes clear) their value as players on the stage of life. Mimi, the invisible architect, cherishes each quirk and flaw as precious facets of her own reconstruction of Lazlo’s world.

The Customer is Always Wrong, p96 Throughout, storytelling is held as the highest good—not just in the exquisitely shaggy authenticity of Mimi’s meandering plotline, but repeatedly in the characters and dialog. One of Madge’s most annoying nemeses is a customer called Neville—a Canadian punk with a fake cockney accent who only redeems himself with his outrageous and plainly fabricated globetrotting autobiographical anecdotes.

This is the real moral of The Customer is Always Wrong above and beyond any free love/expensive cocaine hangover. Very early in the story, Lazlo breaks the fourth wall—speaking to Madge during her job interview, but looking directly into the reader’s eyes, saying “Tell me a joke. Or a Dream. If I like it, I hire you. That’s the way it works.” Several hundred pages later, Madge is about to move to New York and throws herself a going away party.

Madge and Lazlo are on the porch, palavering for the last time. The conversation is weighty and philosophical, and addresses storytelling head-on. “Every day is full of marvels,” Lazlo observes “Everything is struggling to be part of a story.” Then, having by this point stopped using drugs and alcohol, he speculates at length about whether language isn’t just another form of escape, and the conversation grinds into a discursive cul-de-sac.

After an existential heartbeat, Madge remembers a story about a decrepit regular at the diner, and tortured Lazlo lights up—launched from his verbal torpor and encroaching troubles into a full-throttle gale of laughter, from the vicissitudes of Time into the mythological mundane. Sometimes it pays to bullshit a bullshitter.

Images provided by Mimi Pond & Drawn and Quarterly

Over Easy (2014)

272 pp

The Customer is Always Wrong (2017)

448 pp

Drawn & Quarterly, Montreal -

UNDER THE RADAR

Avant-garde artistic movements have a funny way of morphing into the mainstream—witness the fridge-magnet ubiquity of Impressionist paintings, or the integral role of appropriated samples in contemporary pop music. Perhaps the least-known but most influential of these absorptions resulted in the dominant mode of 21st-century visual communication—the CGI animation that now fills every movie, TV, computer and phone screen, and will soon be indistinguishable from so-called reality (unless that already happened and we’re actually in a digital simulation, in which case skip ahead).

As is usually the case, the vocabulary and techniques of the avant-garde were cheerfully corralled into the service of far more conventional art forms—action packed superhero movies, for example—and valued for their invisibility: an almost diametrical inversion of the experimental cinematic tradition that spawned them.

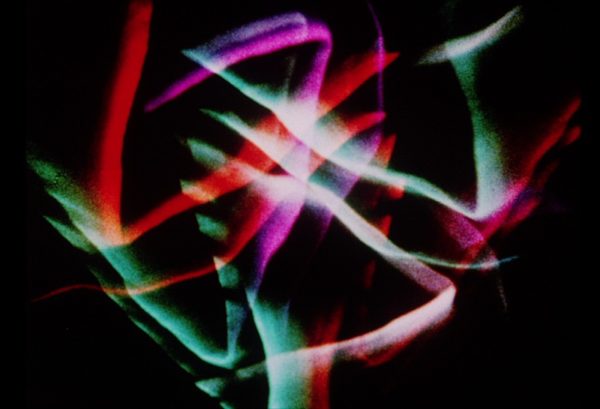

The roots of CGI reach back to the beginnings of cinema, and consist of a parallel history of non-narrative, nonrepresentational filmmaking in which the hardwired formalist mechanisms of human optical perception are allowed to frolic naked across the retina, unencumbered by characters, storylines and any but the most musically abstract dynamic arcs. No wonder it’s often referred to as Visual Music!

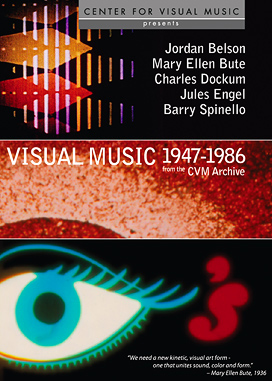

In the last few decades, a global network of nonprofits have sprung up to preserve and disseminate the legacy of this countercultural current. Two worth noting are the Center for Visual Music (in Los Angeles) and the IOTAcenter, both of which have done a tremendous amount of work bringing attention to the work of such abstract filmmakers as Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter, Len Lye, Jordan Belson, the Whitney brothers and longtime head of the CalArts experimental animation program Jules Engel.

IOTA recently put the works of one of Engel’s first students—Adam Beckett, who headed the animation division of the original Star Wars—online at Vimeo and Kanopy (where anyone with an LA Public Library card can watch for free). The CVM’s latest crate-digging extravaganza is a DVD entitled Visual Music 1947–1986, which includes restored gems from Engel, Belson and others.

Charles Dockum, 1966 Demonstration of Mobilcolor Projector. (c) Center for Visual Music All the short films included utilize a variety of pre-digital techniques ranging from the radical DIY of Barry Spinello’s legendary Sonata for Pen, Brush, and Ruler (1968)—produced on a budget of $9 and completely handmade, including the optical soundtrack—to the color organ performances of “illumination engineer” Charles Dockum. The short documentary Demonstration of Mobilcolor Projector (1966) is remarkable in its detailing of the elaborate mechanical craftsmanship that was needed to produce (and record) this time-based visual composition, which—though undoubtedly beautiful—can probably now be rendered with a 99¢ app.

Mary Ellen Bute, Color Rhapsodie (1948)

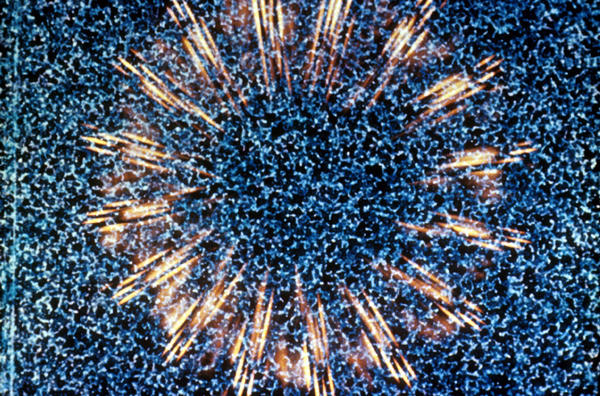

Polka Graph Probably the most revelatory work included here are three works by Mary Ellen Bute, whose “Seeing Sound” animations date back to the mid-1930s—though the pieces included here are from the ’40s and early ’50s. Geometric shapes carefully synchronized to the mathematical structures of the accompanying (light classical) music and the inclusion of the skittering loops from an oscilloscope display make her films sound nerdish, yet they were distributed as pre-feature shorts for mainstream Hollywood movies—making her perhaps the most widely seen abstract animator of the era.

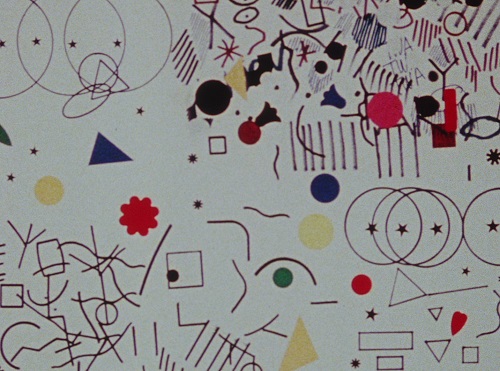

Jules Engel, Play-Pen (1986), (c) Center for Visual Music A close contender would be Jules Engel, who contributed his talents to Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940)—though not on the abstract sequence designed by his beleaguered colleague Fischinger. Engel’s design sense is openly enamored of high Modernists like Kandinsky, Calder and Miro, which is a good thing—especially in the phenomenal Play-Pen (1986) which transcends homage in its pulsing, frantic third act, which combine hand-drawn geometric loops with layered cascades of rapidly mutating symbols—colored squares, triangles and diamonds; Letraset flowers, stars, numbers and letters, all flashing stroboscopically then flipping to inverted colors. Rob Miller’s accomplished classical guitar soundtrack borders on the corny, but Engel’s musical choices are always interesting, so I probably wasn’t listening as carefully as I should.

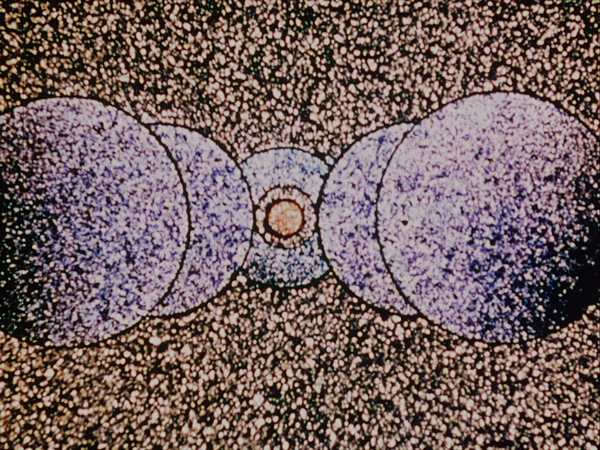

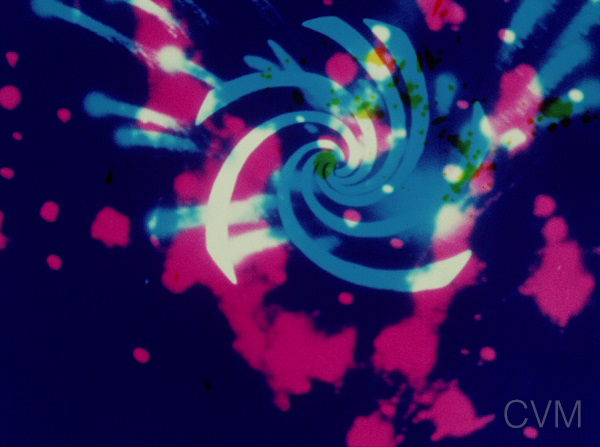

Jordan Belson, Chakra (1972) Scoring was also one of Jordan Belson’s strong suits, dating to the late-’50s when he collaborated with Henry Jacobs on the legendary VORTEX light-and-sound collage happenings at the Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco. The three exercises in spiritual abstraction included here use gamelan, some kind of Tibetan singing bowl/gong dealie, and an original audio collage corresponding to the auditory phenomena associated with the awakening of each of the seven chakras.

This last is, unsurprisingly, the score for Chakra (1972), which purports to fulfill the same function visually—making the invisible spiritual realm visible in objective reality. This is an ambition that holds true for most of Belson’s richly psychedelic oeuvre, which he made with a closely guarded array of secret techniques involving real-time manipulations of light and material.

His glowing, throbbing color-saturated orbs, mandalas, cosmic clouds and showers of sparks are among the greatest works of 20th-century nonobjective art, but Belson withdrew increasingly from the mid-’70s on, removing his films from circulation. The CVM finally got his blessing to release five restored pieces on DVD in 2007—but with the three here, that constitutes less than a quarter of his output (not counting the 20,000 feet of unused effects he shot for The Right Stuff). An artist that is able to maintain their integrity and sincerity while producing such an exquisite and idiosyncratic body of work deserves much wider recognition. But it’s a start.

All images courtesy Center for Visual Music

For more info and to find Visual Music 1947–1986: www.centerforvisualmusic.org/visualmusicdvd

-

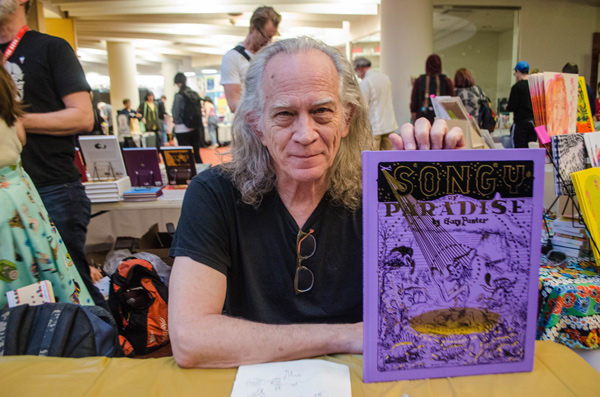

UNDER THE RADAR: Gary Panter

Gary Panter wears many hats—visionary punk cartoonist, Emmy-award winning designer for Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, psychedelic lightshow revivalist, cutting-edge graphic designer, experimental musician, candlestick maker. Having dazzled the comic art world with his elaborate and sumptuous freeform adaptations of Dante (2004’s Jimbo in Purgatory and 2006’s Jimbo’s Inferno), Panter has just released a final, tangential volume—Songy of Paradise, based on John Milton’s 1671 Paradise Regained.

DOUG HARVEY: Can you give a bit of a rundown on your upbringing and relationship to Christianity?

GARY PANTER: I was born in 1950 in Durant, Oklahoma. My father was [a member of the] Church of Christ which considers itself the only true church with a literal reading of the King James version of the Bible. We were lower class people who went to church three times a week and had Sunday school, Wednesday night bible class and singing. The church forbade imagery in worship, musical instruments in worship and orbit dancing and frolicking in general. I was a Christian missionary to Belfast in the summer of 1969—bringing Christ to the Irish religious war. Many things about it bothered me and it took a while to get over, if I did.Do you consider yourself a Christian now?

I am not part of the cult of Jesus. And I am not a fan of organized religion. I am superstitious to an extent. I was raised to try to obey and conform with the end in mind of getting to a better place with the right ritual and magic words, which generally makes no sense. And also the idea that this place is a horrible torturous test seems ungrateful to the gift of some kind of existence—and not digging this one, why would you trust the god to give you an untricky one next? I just have to dig this one as much as possible and not seek THE ANSWER. Interesting questions are enough.So, having spent so much time adapting Dante, why move on to the next biggest Christian cosmologist with Milton?

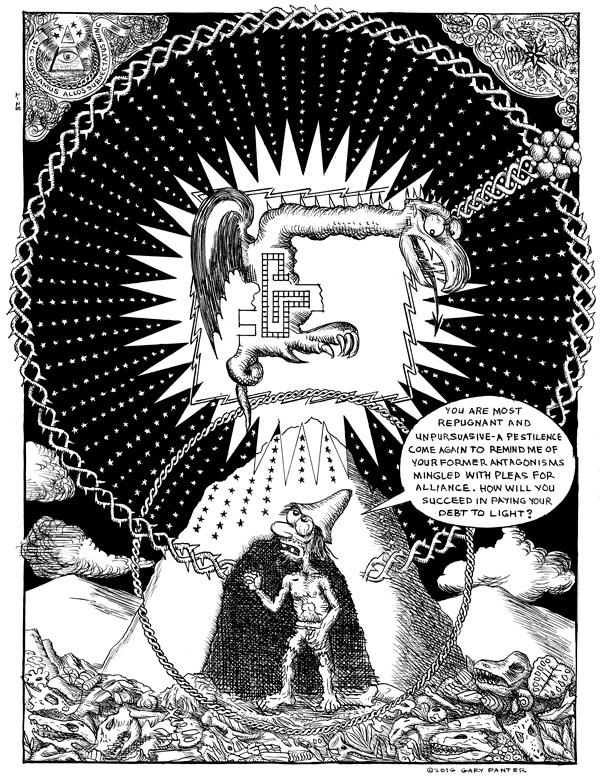

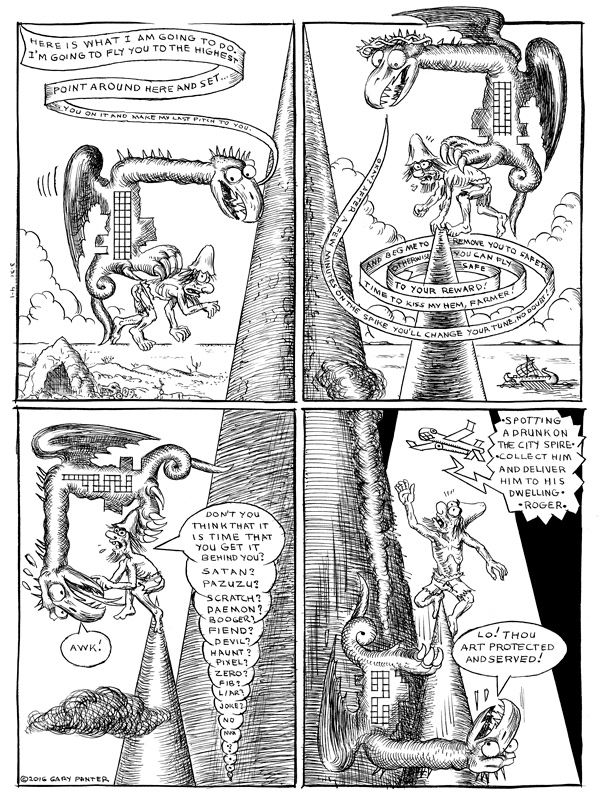

I felt like I had to do some kind of Paradise to finish the trilogy, but I built a lot of Dante’s paradise into Jimbo In Purgatory. I did reference lighting and motifs from Dante’s Paradise in this Milton comic as a background thing.I got a research residency at the New York Public Library. I applied to study Milton and Paradise Regained specifically. It was an amazing situation to have access to manuscripts and an office to read books in. I didn’t know so much about Milton—and maybe I still don’t—but I got the idea from reading a lot of academic writing that Milton was a self-justifying religious pilgrim who found arguments for each change or shedding of skin on his spiritual journey, and he got in a lot of trouble.

What were you trying for formally in SoP? I notice that there are a lot of full-page layouts.

The further I went in the Milton story and in my Milton studies vs. the few verses in the Bible [covering the same story—Satan tempting Jesus in the desert with wealth, power and cheese logs], the less panels seemed required. The action is very limited and the text, aside from the moral teeter-totter quiz, is a show of what Milton knew— texts, places, scholars, kings, myths, and it was not interesting to try to draw everything he mentions.Can you break down the technical aspects of your comic art in general, and SoP in particular?

I work with archaic simple tools. No computer. I use use dip nibs made by Deleter in Japan—the G series. I work on 3-ply Strathmore kid finish bristol drawing paper, though the paper today has more pores and is more problematic than in the past. Pelikan tusche is what I like to ink with—I sometimes leave the cap off to thicken the ink, but you can overdo that. Drawing with these tools makes the work look old-time. Maybe from the early 1800s.

I draw panel boxes with long narrow blunt-tipped striking brushes. The pencils are very tight, drawn and erased over and over and then trying to be better laying down the ink line. I try to never use wite-out and sometimes cut mistakes off the surface with a sharp blade. And I leave a lot of mistakes and try to not make them, but I am not a perfectionist. I want to get the idea across and go on to the next project.A lot of literary comic art seems very much contained in the traditional textual literary culture. Would it be right to say that you see narrative, character, dialogue, etc., from more of a painter’s perspective?

A lot of the comics I have done are formalist procedural strategies that I am exploring or playing out, which sometimes makes for unreadable comics. So it’s good to also do comics like this one that also try to entertain while following some rules to produce them. Larry Poons used systems to arrange the dots on his early ’60s work—that made an impression on me. And also the ever-transforming work of Paolozzi and Fahlstrom. So those are models out of fine art for my comics.Comics are different from paintings typically because they are trying to trap your attention for a while and take you on a little trip and maybe make some aphoristic point or joke. Painting is more of a shorter, arrested, indeterminate moment. A painting is a mood-influencing experience. The history of painting seeps in and the formalism of making and the abstract view and the processing of figuration if there is any, so painting doesn’t seem as linear to me. Though one can take strategies and apply them however you want.

And candle making And what about Pee-Wee?

It was a childhood dream come true, but Hollywood is not my thing. I don’t want to make movies or TV, just handcrafts. Making a lot of candles for the past six months! I love making them. -

UNDER THE RADAR

The He-Man Action Movie Appreciation Society meets regularly to interrogate promising high-budget mainstream shoot-’em-ups in the context for which they were designed—big, loud movie theaters. The Society’s inaugural screening resulted in my report “Is Jason Bourne a 123-minute Psychotronic Blipvert for Hillary?” (lessart.wordpress.com), which ended with a pre-endorsement of The Accountant—“a film that finally addresses the question ‘What if Good Will Hunting was a chick and Jason Bourne banged her and they had an inbred baby that was all like Shine-meets-Transporter and turns out to be the other guy from Good Will Hunting? Whoa.’”

This précis, though based entirely on the impressive trailer that screened before Bourne, is in fact a pretty accurate summation of The Accountant’s conceptual underpinnings. Ben Affleck is an autistic accountant who practices out of a strip-mall in suburban Illinois, but secretly jets around laundering money for drug cartels and terrorists. He knows kung fu and is a deadly marksman, because his dad was Special Forces. But the Treasury Department is onto him! J. Jonah Jameson sends his statuesque African-American data analyst to track Ben down, or else be exposed as the violent teenage vigilante she was! Antics ensue.

The H.M.A.M.A.S.’s most recent screening was actually John Wick Chapter 2, a film that received surprisingly positive reviews, many of which single out the impressive use of actual fine art in the art direction (not to mention the bizarrely Gilliamesque secret hitman telephone exchange!). My analysis of this cinematic milestone will be forthcoming, but I was particularly struck by the inert literalism of JW2’s fine art factor when compared to two brief pictorial incidents that raise The Accountant several notches above the herd.

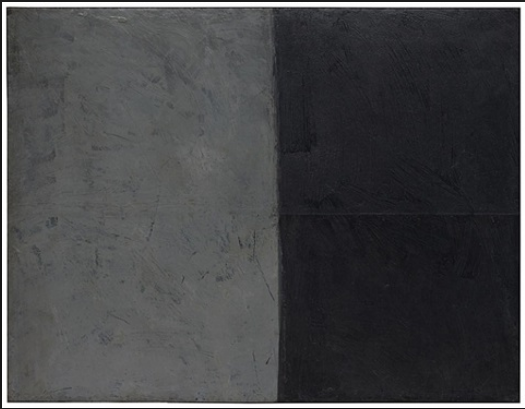

Brice Marden painting The first occurs when young Ben’s parents are visiting some hippie therapist’s autism ranch to see if he can help with their problem child, who sits in the common area working obsessively at a jigsaw puzzle. We don’t see it at first, but in a rapid sequence intercut with the parental consultation, L’il Ben starts going all “Judge Wopner!” because he can’t finish his task, until the resident neurodiverse cutie finds the missing piece and hands it to him. It’s at this point that we get our first actual look at the puzzle he’s working on—it’s a monochromatic gray rectangle, like a Brice Marden painting.

Which isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. In the early ’60s the Springbok company began issuing die-cut puzzles depicting abstract works by Kline, Krasner, Hofmann, de Kooning, and Pollock—whose Convergence was marketed as the most challenging puzzle of all time. Later in the decade, game companies upped the ante by manufacturing puzzles that were completely monochromatic—sometimes on both sides, though I doubt Brice ever saw a dime. And on the surface, the level of cognitive complexity required is what the blank puzzle signals to us about L’il Ben.

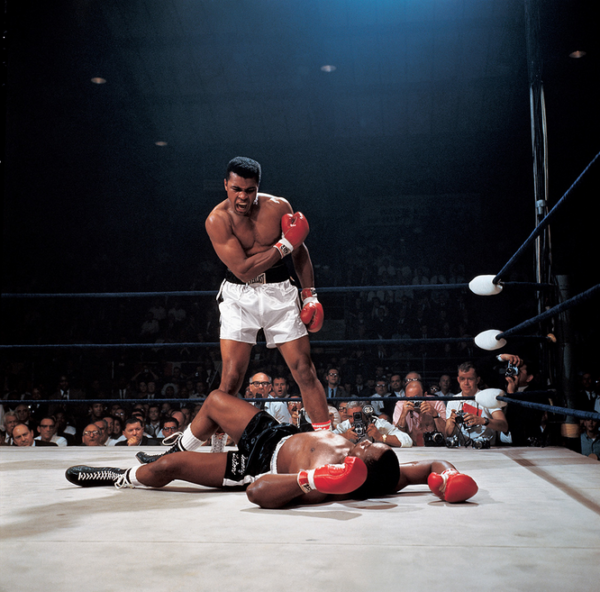

But just as he’s gratefully inserting the last piece to complete the non-image, the camera angle shifts radically, looking up through the glass table, through the gap in the blurry puzzle, framing L’l Ben’s bespectacled eyes. As he snaps the last module into place, the image snaps into focus, revealing that he has been assembling—upside down—Neil Leifer’s iconic shot of Muhammed Ali looming over the knocked out Sonny Liston in 1965. In a few seconds, the filmmakers have established a complex symbolic metaphor —the outsider warrior poet constructed in secret beneath a veneer of unparseable late-capitalist sang-froid; the Emperor card reversed—encoded in an equally (if more esoterically) loaded set of references to the production, distribution and valuation of 2D pictorial artifacts in contemporary culture.Normally, if I perceive this sort of reference to Painting and its Discontents as coincidental—it’s just an upside-down jigsaw puzzle for God’s sake, not some dissertation on the tangled political and phenomenological relationship between photography, the avant-garde and kitsch. But The Accountant brackets its Revenge of the Asperger Ronin storyline with a second, even more explicitly art-historical sight gag, which is set up early, but delivered only in the tying-up-all-the-loose-ends montage—in fact the last shot in the movie before the hero rides off into the sunset.

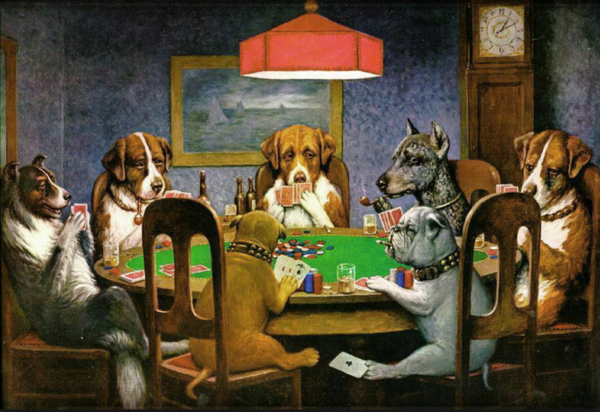

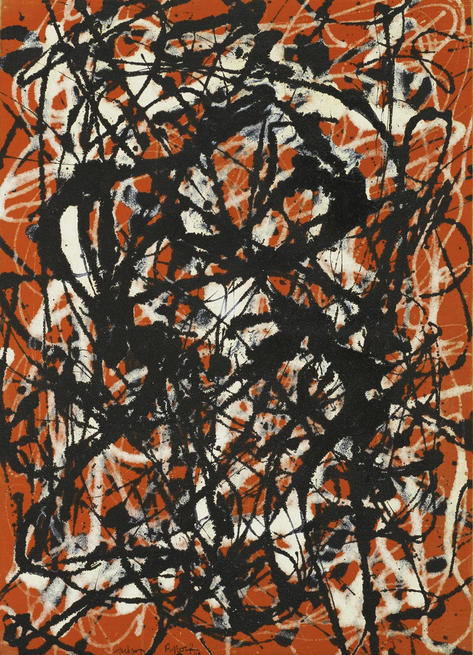

Jackson Pollock, Free Form, 1946 We first glimpse grownup Ben’s art collection when he retreats to his secret storage unit holding his airstream full of currency, weapons and other tangibles—including a decent Renoir and—more improbably—a Jackson Pollock. And not just any Pollock, but 1946’s Free Form (mutated to more than double size), thought to be his very first drip painting. He must have done some real ugly shit for the Rockefellers to score that. So the whistleblower girl in distress is also an accountant, but one who wanted to go to the Art Institute, but Dad said “No,” and she makes an awkward friendship overture to Ben that includes an exchange on the merits of C.M. “Cash” Coolidge’s “Dogs Playing Poker” series. On the run from industrialist mercenary hitmen, she winds up in the trailer and is all like “OMG a Pollock original! You’re not like other accountants.”

Umm… spoiler alert, I guess. Once the antics are out of the way, she’s back at her modest flat and a mysterious package arrives, and here is the second incident. The package contains a stretched and framed canvas, which we see her unwrap and plunk down on her bed with a puzzled, then amused expression. The picture is Coolidge’s A Friend in Need (1903), probably the most famous Dogs Playing Poker image, whose central narrative detail of cheating is conspicuously cropped from our clearest view of it. Distress Girl’s expression goes frowny again, because she notices a surface anomaly in a corner of the painting, pokes around and actually tears away the Coolidge canvas to reveal the gazillion-dollar Pollock beneath. Both Ox and Self overcome, Ben heads off for his next adventure—Jason Bourne vs. The Accountant: The Treadstone Audit. Stay tuned.

-

Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present

Tony Conrad is one of the unlikeliest figures to be the subject of the kind of late-career historical recontextualization that authenticity-starved hipster youth have made their simulacral avant-garde. Don’t get me wrong. His bona fides are all in place; a pivotal figure in 1960s NYC experimental circles—the Velvet Underground was formed in his loft for God’s sake!—but his scattershot oeuvre and authority-destabilizing sense of humor should have conspired to thwart any attempts at canonization.

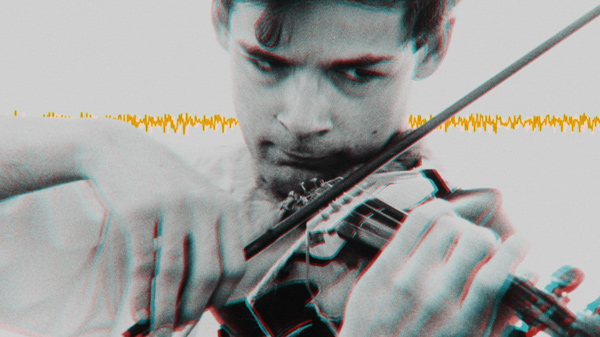

Thankfully, Tyler Hubby’s new documentary Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present—an unintentional requiem following Conrad’s death last April—simultaneously avoids turning its subject into a countercultural icon (mostly by allowing the man himself the lion’s share of screen time) while making a comprehensive—if not entirely coherent—corpus out of his sprawling, peripatetic career.

film still To recap, Conrad was a violin-toting Harvard math student who fell under the sway of John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, then hooked up with La Monte Young, John Cale and others to form the Theatre of Eternal Music (AKA The Dream Syndicate), a microtonal drone music collective whose two-years worth of daily recording sessions remain locked away in Young’s archives. Conrad also joined Cale in the proto-Velvets group The Primitives (alongside Lou Reed and Walter “Lightning Fields” De Maria!) to support the brilliant garage single “The Ostrich” with a tour of New Jersey shopping malls.

He acted in, and scored, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963), a legendary landmark in Queer and Underground Cinema, then made his own hugely influential film called The Flicker (1966), which consisted entirely of alternating sequences of black-and-white film frames, resulting in irregular stroboscopic light patterns that generated visual hallucinations (or vomiting) in the viewer.

Oh yeah, and early on he teamed up with Henry Flynt to invent Concept Art and to picket monolithic cultural institutions like MoMA and the Lincoln Center, though this chapter gets almost no play in Hubby’s doc. He married and began collaborating with Beverly Grant, the actress that played The Cobra Woman in the follow-up to Flaming Creatures, and inadvertently invented acoustic ecology soundscape recordings by jump-starting Syntonic Research’s landmark “Environments” LP series. In the ’70s he produced a series of absurdist cinematic gestures, including pickled and deep-fried films, as well as his notorious Yellow Movies which consisted of cheap house paint applied to paper in the dimensions of a projected film, and left to unfold entropically over the ensuing decades.

film still In 1972 he somehow hooked up with Krautrock pioneers Faust and recorded Outside the Dream Syndicate—an album that fell on deaf ears at the time but has since been recognized as a landmark in genre-blurring experimental drone-rock. After that, Conrad sort of disappeared into academic obscurity, teaching video at SUNY Buffalo from 1976 until his untimely demise. There, he wound up devoting much of his time to cable access programs helping children with their homework and providing a media platform for random members of the Buffalo community through man-on-the-street interviews.

This last period is the most intriguing chapter of Conrad’s career for me, and Hubby’s documentary clearly indicates that Conrad felt the same way. The doc dutifully unfolds Conrad’s gradual reemergence through his collaborations with Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler, the reissuing of the Outside the Dream Syndicate LP and subsequent flurry of archival and newly-recorded experimental epics—including the highly provocative release of a bootleg-quality recording from the Theatre of Eternal Music, over which Young threatened legal action. In his last decade, Conrad was taken up by the Art World, included in Whitney Biennials, feted, collected, anointed and restored.

film still But Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present makes it clear that he was having none of it. He returns to Lincoln Center and is still disgusted. Onscreen he is charming and cherubic, genial and generous, but underlying it all there is a steely refusal to endorse or participate in art forms and systems that solidify into authoritarian power structures. From the POV of the glamorous art world, Conrad’s story is one of the happy restoration of the reputation of an Important Historical Figure found shuffling around in the Media Arts Department of Buffalo U—but the real story here, and what makes this an extraordinary and timely documentary, is that for Conrad there was an unbroken continuity between the elimination of the composer in the collaborative performances of the Dream Syndicate, and groping for the common denominator of 87 with Cherise on the Homework Helpline. Lincoln Center can’t touch that.

THIS THURSDAY Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present, directed and written by Tyler Hubby, March 16, at the Theatre at ACE Hotel DTLA; for more info click here

Additional screenings at these locations: March 21-26, Ann Arbor Film Festival; March 24, San Francisco Cinematheque at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts; March 31-April 6; one week run at Anthology Film Archives, NYC; other info:tonyconradmovie.com

-

UNDER THE RADAR

I first became aware of the remarkable documentarian Adam Curtis a few years ago, when I stumbled across The Century of the Self, a four-part television program exploring the birth of the public relations industry by way of the career of Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays. The sheer amount of historical detail was a little overwhelming (a hallmark of Curtis’ work, I later learned), but it offered an unusually cogent explication of the difficult idea that the entire consumer culture in which we are embedded began as a deliberately crafted social fiction—in other words, an artwork.

As I became more familiar with Curtis’ BBC films (which date back to the 1980s), I began to suspect that they themselves were artworks of considerable sophistication, whose playful and subversive collage aesthetics were camouflaged by the authoritative documentarian framework—as if Bruce Conner had been recruited to run the History Channel. Many of the rapid-cut found-footage fragments seemed to bear no relationship to the convoluted narratives spoken over them, but were instead chosen for their sheer formal beauty or curiosity value.

Then again, sometimes what looked like a shakily beautiful handheld landscape sequence à la Brakhage will suddenly snap into contextual significance with the appearance of some explosion or key figure exploding. Curtis basically has access to an extraordinary wealth of BBC archive footage, and is constantly amassing more. And he is equally adept at unearthing historically compelling vintage newsfeeds and cinematic snippets of sociological significance as he is at spotting a passage of chance cinematographic beauty buried in hours of forensic video journalism.

I wasn’t sure how self-consciously artistic Curtis was being, until I learned that he cites semiotic/formalist collage master Robert Rauschenberg as a major influence. Cool! To a visually oriented viewer, Curtis’ dense pictorial narratives (and deft, if manipulative, soundtracking) are as overwhelmingly stimulating as the DIY cut-ups of Craig Baldwin or the legendary Los Angeles public-access-TV antics of the Three Geniuses. On top of all this, however, he drizzles a web of interdependent historical anecdotes detailing various nefarious antics of the apparently eternal war between the Discordians and the Illuminati.

Just before the Clinton-Trump showdown, I began to hear a buzz about a new, almost three-hour film by Curtis to be released specifically for the proprietary BBC iPlayer, which only works in the UK. Of course, it was on YouTube and The Pirate Bay the next day, and I’ve since watched the film—entitled HyperNormalisation—several times. HyperNormalisation takes its title and underlying thesis from the idea put forth by Berkeley social anthropologist Alexei Yurchak concerning a Matrix-like false consensus reality that took hold as the Soviet (and by ‘patacritical inference American) empire neared the end.Curtis’ journey begins with the near economic collapse of New York City in 1975 and the simultaneous double-dealings of Henry Kissinger in the Middle East. From this binary configuration, Curtis derives all manner of subtexts, including detailed and illuminating histories of suicide bombing and Muammar Gaddafi’s ridiculously mutable role in American PR strategies of global misdirection. Along the way, he finds time to make gratuitous fun of Patti Smith and Jane Fonda, credit EFF founder John Perry Barlow with the invention of anarchism, and seemingly tie it all together with a YouTube video of some teenaged-girl named Miranda Duncan (and friends) lite-twerking to The Wop.

Not that I mean to dismiss the strength of Curtis’ political insights—it just isn’t that easy to discern what they are. Does he really believe that bankers only started taking over governments in 1975 (Medicis anybody?) or the hoary liberal chestnut that Occupy failed because they wanted to just tear everything down without a clear idea about what to replace it with? Perhaps the most telling sequence in HyperNormalisation is one in which he profiles Vladimir Putin’s right-brain man Vladislav Surkov, who Curtis describes—with a certain awe—as someone who has applied the theories of the postmodern avant-garde to the theater of global politics.The problem facing the gnostic documentarian is not to persuade by rational analysis or even hyperbolic counter-propaganda—we know this from the negligible impact that Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 911 had on the 2004 election—but to find a combination of pictures, sounds, symbols and stories that will snap the hapless viewer awake to the reality of the Matrix. I don’t think Curtis is quite there yet, but hopefully he’ll hit on the formula sometime in the next four years. Say “Bye,” Heather!

-

UNDER THE RADAR

Installation artist and drone improviser Gabie Strong has been a playa in the surprisingly vigorous Los Angeles experimental music community for some time, with her radio show Crystal Morphologies as one of the anchors of pirate radio KCHUNG’s programming lineup for the last five-plus years. She has just expanded the Crystal Morphologies umbrella to include a record label, dedicated to “experimental and drone music informed by the artist’s hand” as well as “unclassifiable, composed and improvised work by women, whose contributions have often been overlooked in the context of avant-garde and improvised music.”

Cover art for Spectress by John Pearson. It’s always best to start with what you know (and own the rights to), so Crystal Morphologies’ first two vinyl/cassette releases are works by Strong herself—four side-long live recordings—two from this year (Spectress) and two from last year (Sacred Datura/Peaked Experience). True to the label’s mandate for hand-informed sonics, Strong’s work has a vintage, pre-digital feel to it and a lineage that—while touching on Japanese and continental precedents—dates back to the whole La Monte Young–Marian Zazeela–Tony Conrad–John Cale Theatre of Eternal Music outburst, up to and including Lou Reed’s notorious Metal Machine Music.

As with all the best noise music, it’s often hard to separate out what’s making what noise. Spectress’ “Sunset Circuit” may employ guitar, effects, synthesizer and vocals, but it shifts almost imperceptibly between soundscapes—evoking the propulsive force of a jet engine and the amniotic calm of the ocean depths with nary a strum or arpeggio in earshot. The flipside, “Taphthartharath,” performs a placating ritual on that mercurial spirit, morphing ominous bomber drones and clinical vintage synth sine waves and static into an ethereal virtual pastorale fading slowly to the sounds of digital crickets (which I initially mistook for the sound of my window fan malfunctioning. Respek!)

Spectress and Sacred Datura/Peaked Experience album art The Sacred Datura/Peaked Experience pairing uses less of an overall dynamic arc, though both works cover a wide variety of aural terrain. “Sacred Datura” combines buzzsaw feedback, pulsing chimes, vacuum cleaner phasing, and distorted vocal loops, while “Peaked Experience” forefronts old school knob-twisting oscillations and heavy reverb, served on a bed of shredded electric guitar with a side of electronic bird chirps.

Putting out vinyl and cassette releases is a way of reasserting the curatorial dimension of the small record label business, much of which has been dissolved in the miasma of cyberspace. With these two Strong releases (haha) and forthcoming cassettes from Geneva Skeen, Christopher Reid Martin, and Renee Petropoulos, Crystal Morphologies may be stepping up to carry the torch passed from LAFMS, Melon Expander, and the late Michael Sheppard’s Transparency label—among many others—as LA’s latest virtual exhibition space for experimental sound. There’s certainly enough noisy artists out there.

Fitting into a narrower and less local tradition (see Charles Amirkhanian’s 1750 Arch Records) comes Spoken Records, a foray into the even-more-obscure genre of text-sound composition, which—as its name suggests—uses spoken words as the primary material for its musical innovations—often at the expense of literary intelligibility. Such is not the case with Spoken Record’s debut release, however.

Greetings From Here: Audio Postcards In Transition by label founder Pauline Gloss consists of nine short epistolatory communiques, recorded quickly and simply on the artist’s laptop computer. While layering vocal tracks and adding tasteful concrete elements, Gloss’ texts have more in common with confessional autobiographical poetics than Hugo Ball’s “Karawane,” weaving stories of institutionalization and gender indeterminacy into quite coherent—if elliptical—narratives. It reminds me of nothing so much as the poet Anne Sexton’s amazing recording for poetry label Caedmon, with Gloss’ NPR-ready baritone even resembling Sexton’s tobacco-and-vodka cured delivery.

A solid work of art, it’s also a courageous and unpredictable flagship for a label devoted to text-sound, many of whose proponents are adamantly nonsensical. Like Crystalline Morphologies, Spoken Records is already plotting its expansion out of the vanity press division, by way of an open call for “stand-alone works of literary sound art” that will be compiled in a series of vinyl singles for distribution. Something for the jukebox in the Cabaret Voltaire!

http://www.crystallinemorphologies.com/

http://www.spokenrecords.com -

UNDER THE RADAR

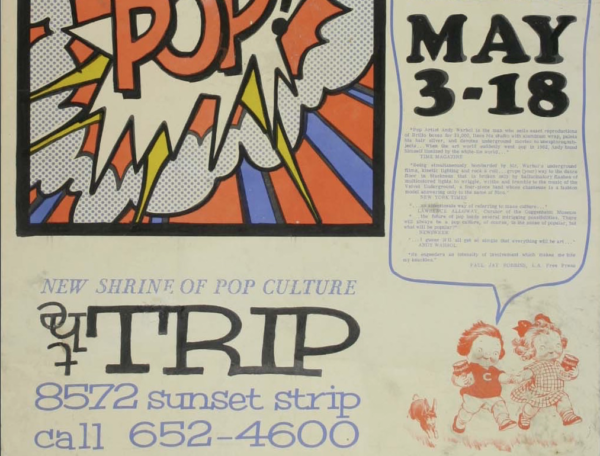

Fifty years ago—in May 1966—the Velvet Underground played their legendary West Coast debut at Hollywood nightclub The Trip as part of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable. On the first night, the joint was packed with curiosity-seeking hipster celebrities; Cher famously declared, “They will replace nothing, except maybe suicide.” But on the second night, the place was empty except for five people. One was Kurt Von Meier, a UCLA art historian who played a key role in the Red Krayola’s early career before writing a 350,000 word essay on Duchamp’s ball-of-twine readymade (it’s online!). The other four were also art world figures: Stanley and Elyse Grinstein and Sid and Rosamund Felsen.

If Rosamund had done nothing else after that night, I’d be impressed. But, as it turned out, she went on to found and operate one of the longest-running and most influential commercial art galleries in Los Angeles, representing, at one time or another, most of the major players to emerge in the ’70s and ’80s art world in LA and environs, including Mike Kelley, Chris Burden, Lari Pittman, Marnie Weber, Jim Shaw, Jeffrey Vallance, Karen Carson, Paul McCarthy, William Wegman, Alexis Smith, Chuck Arnoldi, Erika Rothenberg, Meg Cranston, Pat O’Neill, Jason Rhoades, Laura Owens, Kim MacConnell, Steve Hurd… you get the picture.

The other side to Rosamund’s superstar stable was the equally compelling roster of idiosyncratic artists’ artists like Richard Jackson, Jacci Den Hartog, Steven Hull, Nancy Jackson, Jimmy Hayward, Marc Pally, Tim Ebner, Jean Lowe, Pat Nickell, Pauline Stella Sanchez, Grant Mudford (Rosamund’s spouse) and M.A. Peers (my spouse). Because of M.A.’s nearly 20-year association with the gallery (and my own friendship and professional association with a number of RFG’s other artists), I got a pretty good insider’s view of Rosamund’s modus operandi.

Contrary to many horror stories I’ve heard about other local contemporary dealers, Rosamund is unconditionally supportive of her artists’ creative autonomy, and their need to develop and experiment over time, regardless of sales. Once she is convinced of an artist’s merit, she trusts their vision. She has an excellent eye, an open and curious mind, and a very individualistic sensibility, which allows her to champion artists with unlikely or unfashionable ideas or styles. Rosamund also has a strong and confident instinct for elegant and aesthetically sophisticated exhibition design.

All four of the buildings that RFG has occupied have been remarkable exhibition spaces in their own right. The legendary first space on La Cienega Boulevard had previously been the home of Riko Mizuno and Gagosian galleries, and was the site of many landmark exhibits— including Burden’s Big Wheel (1979) and Kelley’s Monkey Island (1987), including his stuffed animal magnum opus More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid.)

Rosamund had kind of stumbled into the gallery business. That night at The Trip, the Felsens and Grinsteins were in the very first stages of establishing Gemini GEL, the ambitious commercial fine art printmaking shop that played a significant role in LA’s ascendency as an art world player in the ’60s and ’70s. Rosamund began as the shipping clerk, but was operating in a curatorial mode by the time she left in 1969 over disagreements with master printer Ken Tyler. She moved over to the Pasadena Art Museum, where she was registrar and curator of prints until Norton Simon’s hostile takeover spelled the end of that institution’s golden era. Rosamund was preparing to go back to attend UCLA when a casual acquaintance named Timothea Stewart needed help running her new gallery on La Cienega Boulevard.

That first show with Timothea was a labor of love devoted to the late Wallace Berman. Rosamund sat behind the desk. The exhibit closed after five months with no sales, and Timothea apparently decided she had played her one good hand and was ready to fold. But suddenly everyone was going “Rosamund, you should take over and open your own gallery.” And she was all like ”Who me?” But then she was all like “Why not?”

After a dozen years, RFG moved to an even bigger, more beautiful gallery—the former Santa Monica Boulevard studio of photographer Tom Kelley, who had taken the Marilyn Monroe nude calendar photo. Inspired by the paintjob on contractor (later gallerist) Frank Lloyd’s pickup, she had the building painted yellow, which eventually inspired Jason Rhoades’ career-making Swedish Erotica and Fiero Parts (1994) installation.

McCarthy’s “Bossy Burger” Felsen continued staging landmark shows such as McCarthy’s “Bossy Burger” and Jeffrey Vallance “Presents The Richard Nixon Museum” (both 1991), but the art-market crash led her to relocate to Bergamot Station, and an exodus of her star artists to dealers who were more inclined to participate in the emerging global art supermarket. Rosamund’s vision seemed to grow more personal, and she began taking on more woman artists, including non- (or neo-) Angelenos like Joan Jonas and Mary Kelly.

About a year ago, as Bergamot imploded, RFG made an ambitious leap of faith to a newly remodeled space on Santa Fe Avenue, but the art world being the seething vortex of poisonous psychic vampirism that it is, couldn’t support the new venture. Early this summer, it was announced that the next show at RFG would be its last—in its permanent physical space anyway. RFG will continue to represent many of its artists, maintain a virtual presence online, and rematerialize as needed for whatever pop-up or art fair opportunities present themselves. (Which may be the new default mode for art galleries.) But Rosamund’s always been ahead of the curve. What was her assessment of the proto-punk feedback drone pioneers The Velvet Underground back in the summer before the summer of love? “Terrific.” Take that, Cher!

-

UNDER THE RADAR

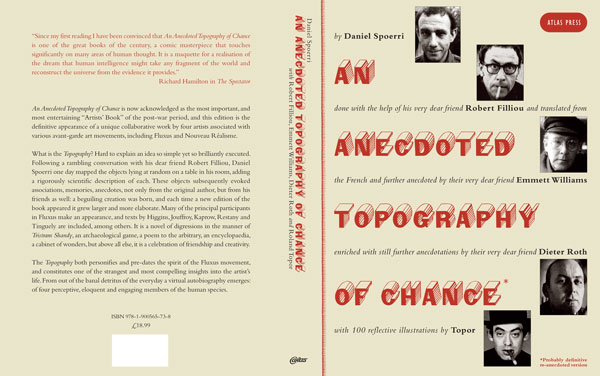

The mighty Atlas Press—London-based purveyors of “pataphysical texts,” Dada documents, Viennese Aktionist manifestos, and Oulipo anthologies—has reissued a legendary art book that uses a tabletop cluttered with the detritus of daily life as a jumping-off point and ultimately comprised a postmodern who’s who of the international avant-garde from the 1960s.

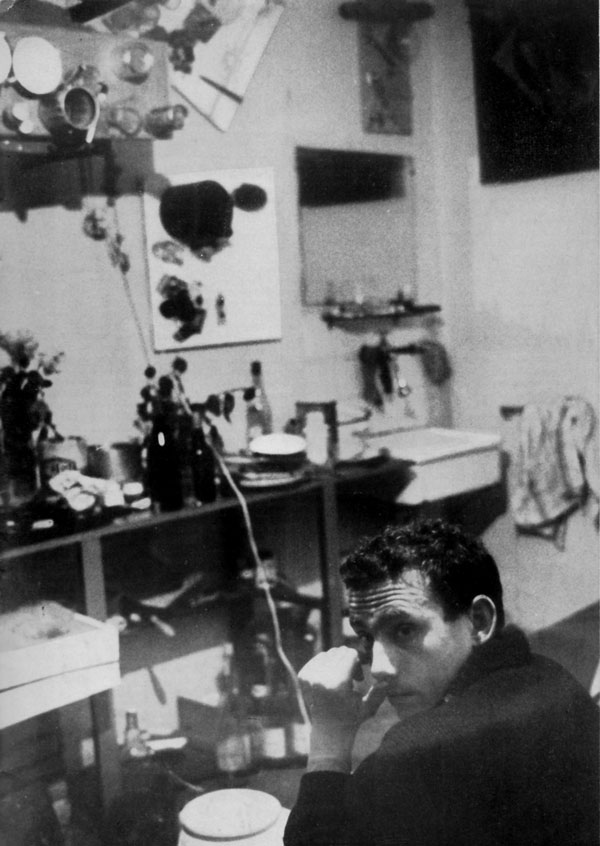

Atlas Press cover In 1961, Daniel Spoerri—a Swiss/Romanian dancer and avant-garde theater impressario turned Nouveau Realisme artiste—had only recently embarked on the “Snare Pictures” for which he became renowned—the leftovers from a meal secured to the surface of a table, then rotated to hang on a wall like a painting. For an exhibition of these works in Paris, Spoerri devised An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, a 54-page booklet mapping all the objects on the table in his Parisian flat, then forensically extrapolating from them in “the way of Sherlock Holmes” to create a fragmentary autobiographical literary masterpiece.

Atlas Press. An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, Daniel Spoerri photo. The Anecdoted Topography took on a life of its own. With initial assistance from Robert Filliou (discoverer of “Art’s Birthday” and a laborer for the Los Angeles Coca-Cola plant in the late 1940s!), and subsequent translations and expansions by Emmett Williams (European coordinator of the Fluxus movement and Editor in Chief of Dick Higgins’ Something Else Press) and Dieter Roth (literary sausage-maker and auteur of decay), the slim volume has quintupled in size since its first edition.

The more than 80 entries consist of a description of the article—a box of matches, a jar of instant coffee, a green Swingline stapler, wine stains, scotch tape, etc.—with Spoerri’s deadpan description and any anecdotal information accounting for its presence on the table. With each translation and republication, further layers of commentary were added, and responded to. The artist/writer/filmmaker Roland Topor contributed a scratchy line illustration for each entry. The anecdotal digressions diverge exponentially at the first branch, and often in Spoerri’s initial log.

The effect is a curious mixture of an ahead-of-the-curve conceptual literalism and absurdist free association that’s as funny and innovative as Flann O’Brien’s footnote-laden The Third Policeman or Alfred Jarry’s Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician. Its sheer arbitrariness is something of a miracle, a form of haruspication—predicting the future from animal entrails, dummy!—that demonstrates how, in the human imagination at least, we can see infinity in a grain of sand. So what if it’s an infinity of sand?

The floor of Catherine Howe’s studio, Germantown, 2011, courtesy of the artist. Such lofty philosophical concerns don’t intrude on Jonathan Griffin’s On Fire, although it shares the same kind of dispassionate repertorial premise and alchemical agenda. A 100-page anthology compiling short profiles of 10 artists whose studios caught fire (most of them catastrophically), On Fire also possesses a remarkable literary tension produced by the dissonance between the mundane particularities of the case studies and the archetypal devastation that every oil-painting student has drilled into them. Sometimes that devastation manifests as predicted, other times not.

The book came to my attention because I’m quite familiar with one of the incidents—the total destruction of Christian Cummings’ Pasadena studio (several of the artists profiled are in LA, where the book originated—though the fire reaches as far as Berlin), which destroyed the almost-finished sequel to CC’s Slavebation, his 2012 album of avant-garde visionary song-poems which I described in an earlier Artillery column as “the first great protest album of the 21st century.”

This loss, along with the incineration of all of Cummings’ musical instruments, isn’t even mentioned in his account of the conflagration, which actually devotes a considerable amount of attention to his current obsession with rare cacti. He seems equivocal about the fire’s significance, suggesting that he feels he’s dodged the bullet of commitment that a professional workplace represents. He also says, “It would have been better if I lit the match myself.”

If Cummings’ portrait is the funniest and most unconventional, the most improbably compelling is the last—Brendan Fowler’s blow-by-blow account of the legal fallout after his (and Matthew Chambers’) Glendale studio was consumed by a fire spreading from a next door furniture factory. Chambers’ account opens the book, and the bracketing by two related narratives points to the organic word-of-mouth branching that determined its subjects. I would’ve liked to have heard from some less conventional artifact makers—The Institute for Figuring, for example, whose Chinatown facility was burnt out in 2013. But On Fire makes no claim to comprehensiveness, and in its way is as much a chance-determined group autobiography as the Anecdoted Topography.

An Anecdoted Topography of Chance

Daniel Spoerri, with the help of

his very dear friends Robert Filliou, Emmett Williams and Dieter Roth, with drawings by Topor

274 pp.

Atlas PressOn Fire

Jonathan Griffin

98 pp

Paper Monument -

Art of the Prank; NOTFILM

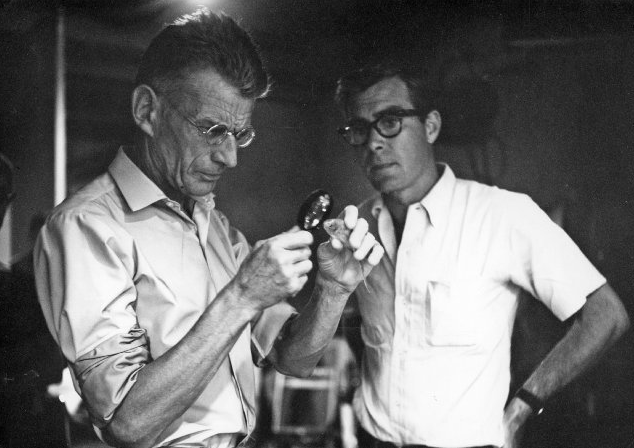

Ross Lipman, the legendary film restorationist responsible for preserving the cinematic legacies of Bruce Conner, Kenneth Anger, John Cassavetes, and a cluster of forgotten American neorealist gems including Killer of Sheep and The Exiles, has turned his attention to a more high-profile form of film history with his expansive examination of Irish literary genius Samuel Beckett’s sole foray into the movies—1965’s short silent narrative Film, starring Buster Keaton in one of his final screen roles.

Buster Keaton in Notfilm (2015) Lipman takes a notoriously opaque 20-minute wordless black-and-white philosophical chase scene, and unpacks two hours worth of historical context, biographical insights, conceptual musings and structural poetics into NOTFILM (2015), his complex and moving documentary— also black and white, but rarely wordless (except to emphasize the gorgeous score by Bela Tarr’s main man Mihály Víg). While there’s plenty of down-to-earth making-of grit to feed the viewer’s narrative appetite, the heart of the story is Beckett’s and Keaton’s respective takes on being and nothingness, and who gets to watch.

Samuel Beckett in Notfilm (2015) Charged with the restoration of the avant-garde milestone, Lipman developed a fascination for the work, with its reflexive implications about the ethical and psychological dimensions of cinema, and its curious identity as the meeting ground for two diametrically opposed but deeply similar geniuses of 20th-century culture.

Lipman appears to have developed his obsession just in time, as several of the participants—particularly Beckett’s go-to actress Billie Whitelaw and Grove Press publisher and Film producer Barney Rosset are themselves teetering on the brink of the Void in their interview segments. Rossett, whose flickering memories of a missing prologue to the Beckett short sparked Lipman’s passion, was the source of the missing footage as well as surreptitious audio recordings of the pre-production meetings.

Joey Skaggs on the farm in Kentucky, Art of the Prank, Relight Films Luckily, Lipman’s scholarship and curiosity are up to the task, and ultimately wind up overshadowing the archival snippets to be the elements of this layered scholarly collage that stick with you after the curtain falls. The balance tips the other way in Art of the Prank Andrea Marini’s long-awaited career-spanning overview of the disruptive antics of media prankster Joey Skaggs, whose work holds a mirror up to his medium in a more interventionist way.

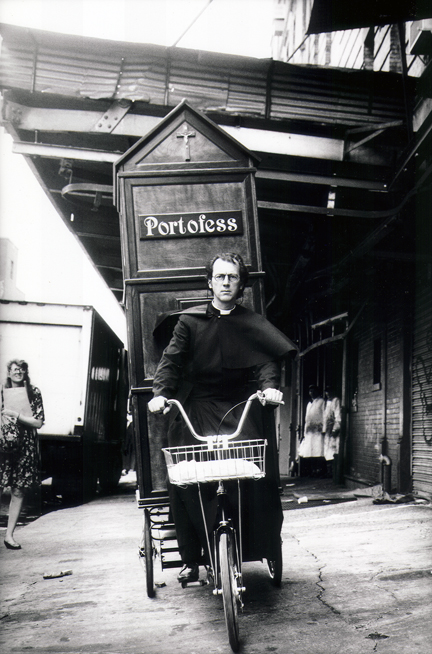

Joey Skaggs in Art of the Prank, Relight Films It’s not that there’s any lack of historical context, biographical insights, etc.—but the wealth of historical documentation delivers the real meat of Skaggs’ practice, next to which any discursive analysis pales. Since the late 1960s, Skaggs has been planting absurd fake news events into the mainstream media—often staging elaborate theatrical hoaxes with actors, sets, fake websites and business cards and press releases—only to pull out the rug at the peak dramatic moment—to the consternation and embarrassment of the infotainment professionals. Usually the only recourse for big media is to exact revenge through unflattering or distorted profiles—which is why this fair and balanced account is so welcome.

Joey Skaggs as a priest pedals his Portofess, Art of the Prank, Relight Films Skaggs’ conscious practice as a media hoaxer dates back exactly 40 years to April Fool’s Day of America’s Bicentennial year, when he dramatically revealed the fictional nature of his highly publicized Cat House for Dogs in court, having been subpoenaed by the Attorney General of the State of New York. That moment was captured on video, and is included in Art of the Prank along with archival documentation of the diet-enforcing mercenary Fat Squad, the Fish Condos, Celebrity Sperm Bank, Dog Meat Soup, WALK RIGHT!, Dog Meat Soup, Maqdananda the Psychic Attorney, and Skaggs’ heroic attempt to windsurf from Hawaii to California.

Joey Skaggs in Art of the Prank, Relight Films Many of these have unique underlying social or political content. But together they comprise a sustained multivalent attack on a culture that nurtures, sustains, exploits, and even enforces the gullibility of the public. One aspect of the story that this film brings to light is how Skaggs’ deceptive practice evolved directly out of young Joey’s frustration at the sluggishness and lack of autonomy in his chosen field as a visual artist. The entire symbolic ocean in which we swim, which most of us take for reality, is revealed to be a fabrication. Or as Joey puts it “If I believe that, what else do I believe that’s total bullshit?”

NOTFILM

Milestone Films

Written by Ross Lipman

2015 / 128 minutes

NOTFILM screened in LA April 1–9 at various locations

http://filmbysamuelbeckett.com/updates/Art of the Prank

Relight Films LLC

A Film by Andrea Marini

US / 2015 / 84 min.

Art of the Prank screens in LA April 10th at 8 PM presented by Slamdance Cinema Club at the Arclight Hollywood

http://www.artoftheprank-themovie.com/screenings/ -

UNDER THE RADAR