I have a confession to make: I am Miroslav Kyropnik! (crickets) One of my sub rosa projects at UCLA was the creation of a body of work by a totally fictional outsider artist who took found photographs, magazine illustrations, and art reproductions and added speech balloons praising himself to the heavens. I then dropped the results into thrift stores and awaited their discovery and—depending on the response—either my big reveal or discovery of a trove of unsuspected Kyropnik originals. Still waiting …

What brought this to mind was Brett Ingram’s recently published monographic volume The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler. Purporting to show the previously unsuspected outsider magnum opus of an aged (now departed) scientific illustrator at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, TSWoRK, made me suspicious right off the bat—mostly because Kuhler was just too perfect.

According to the official backstory, Ingram—a former space shuttle engineer turned multimedia artist/consultant—first ran into Kuhler on a bus in Raleigh. A tall and garrulous figure, Kuhler sported a white beard and ponytail, and was wearing a bizarre handmade uniform with brass buttons, epaulets, short pants and a Boy-Scout style neckerchief. He delivered a loud stream-of-consciousness monologue before disembarking a couple of stops before Ingram’s, leaving an indelible impression.

A couple of years later, Ingram got a gig at the museum and lo and behold, behind door #2, and the rest is history. Gradually opening up about his elaborate imaginary society— Rocaterrania, a small splinter country in upstate New York founded by Eastern European immigrants who couldn’t abide the concept of democracy—Kuhler seemed to be the ideal outsider artist—eccentric, erudite, high-functioning, photogenic; yet responsible for a private universe as detailed and idiosyncratic (almost) as Henry Darger’s outsider nations of Glandelinia and Abbieannia.

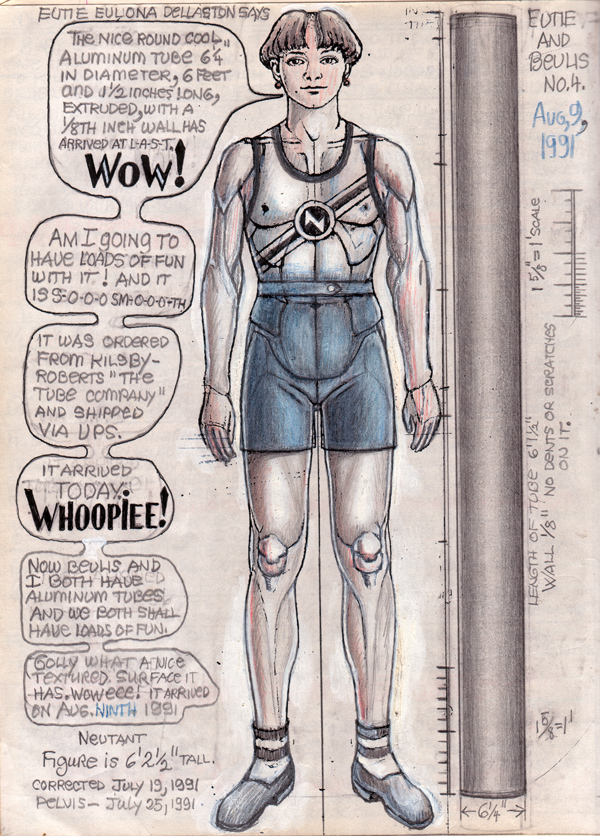

Conceived in 1948, when Kuhler was a miserable precocious teenager stuck on a ranch in Colorado, Rocaterrania evolved over the next 60 years, reflecting the practical challenges and psychological struggles in the artist’s life through convoluted genealogies, historical intrigues, urban renewal, propaganda, linguistic experiments, and sci-fi–tinged social engineering—particularly cruel Empress Catherine’s wide-scale neutering of orphaned children and juvenile delinquents to create a class of “Neutants.”

All of this was copiously illustrated in a range of graphic styles, primarily pen-and-ink crosshatching and stippling with an old engraving type vibe, which strangely, over time, began to resemble the work of underground cartoonists—R. Crumb, Kim Deitch and Jim Woodring all come to mind. Kuhler’s elaborate calligraphy—a mutated Cyrillic font—rivals the exquisite psychedelic penmanship of Rick Griffin.

Kuhler also worked in colored pencil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and mixed media, as well as fashioning baroque smoking pipes out of bric-a-brac, various models (including a life-size mannequin of his neutant surrogate Peekle Hannaford). He filled scrapbooks, diaries and sketchbooks, and had dozens of versions of that crazy uniform—for the Rocaterranian National Labor Service.

Another red flag is the way the book is structured. There’s a brief intro with details of his early bio—born in Jersey to a famous German train designer and an icy Belgian mama, moved to upstate New York, sent to boarding schools where he was bullied, uprooted to the ranch at age 16. After that, it’s pretty much a deadpan presentation of the history of Rocaterrania, as if Kuhler had decided to share his vision in a self-published academic tome, devoid of irony, interpretation or context. It’s all like “Here are the diagrams of the streetlamps lit by methane gas harvested from Rocaterranian poo (See fig 187)”—a brilliant editorial aesthetic decision, but suspect. Where were the Joseph Campbell quotes? The queer theory deconstruction?

I decided to call Ingram’s bluff and contacted him: “You made this all up didn’t you? That dude looks just like [LA collector] Stuart Spence.” I explained, “He’s already confessed to me,” I lied. “All charges will be dropped.”

“Made what up?” he responded via email, “Rocaterrania? Not a chance. I wish I were that imaginative! You’ll see when you get the movie. The term ‘true original’ is often overused, but Renaldo really was a nation unto himself.”

The movie in question is entitled Rocaterrania. Ingram sent me a copy, and he was right. The more traditional biographical documentary approach had already been done, and done right. Extensive interview footage of Kuhler himself show him as a remarkably self-aware artist, an adamant non-conformist, a deeply compassionate and ethical (dual) citizen, and an outrageous prima donna. The power of creativity to compensate for profound psychological trauma has rarely been more clearly demonstrated.

I must recommend that you purchase both the book and the DVD to get the story from both angles. And forget what I said about Miroslav Kyropnik. I was just pulling your leg. Wait until you see the movie. Now where did I leave Stuart Spence’s number …?

0 Comments