We are in the midst of the information age, with archives and libraries overflowing, and records piling up like plastic in the ocean. How does personal value translate to cultural value, or is it the same thing? Who decides what is worth preserving? How should collectors and archives and individuals interact?

These are questions posed by author/sound curator/musician/audio artist Robert Millis in the introduction to his lavish new 244-page, full-color hardcover-book-and-double-CD package Indian Talking Machine, a highly personal account of his stint as a Fulbright Scholar in 2012-13 studying the early music industry in India.

Robert Millis in Bangalore

While he’s referring specifically to his encounters with an eccentric cast of 78 RPM hoarders in the second-most-populous country in the world, he could easily be describing the driving questions behind most of his own icebergian activities, of which ITM is just the tip, as well as those of a generation of intrepid amateur songcatchers that seemingly sprang out of nowhere over the last decade or so, and the equally unlikely hipster consumer base that eats this stuff up.

As one of the mysterious co-conspirators (along with former Sun City Girl Alan Bishop) of the indie world-music record label Sublime Frequencies, Millis has a legitimate claim as one of the architects of the New Model Ethnomusicology, which celebrates impure hybrids, avant-garde recontextualization, and radical auditor subjectivity—beautiful fragments of street music performance emerging fading from urban soundscape recordings; collages of bootlegged shortwave broadcasts; compilations of vintage Cambodian pop music cassettes scavenged from public libraries in California.

Millis’ particular specialty has been collections of 78 RPM records, including the unimpeachable Burmese Crying Princess and Scattered Melodies: Korean Kayagum Sanjo collections for SF, and an ostentatiously eclectic book/CD package called Victrola Favorites for the Dust-to-Digital specialty label—the high-tone culmination of the cassette anthologies of old 78s that Millis had been releasing with Jeffery Taylor (his partner in Seattle-based experimental band Climax Golden Twins) since the mid-’90s.

HMV sleeve detail

That 2007 publication bears considerable resemblance to Indian Talking Machine, largely because it shares the same designer—John Hubbard, who excels at establishing and modulating moods from sequences of documentary photos (though I wish he would recognize the cardinal wrongness of double-truck photo spreads).

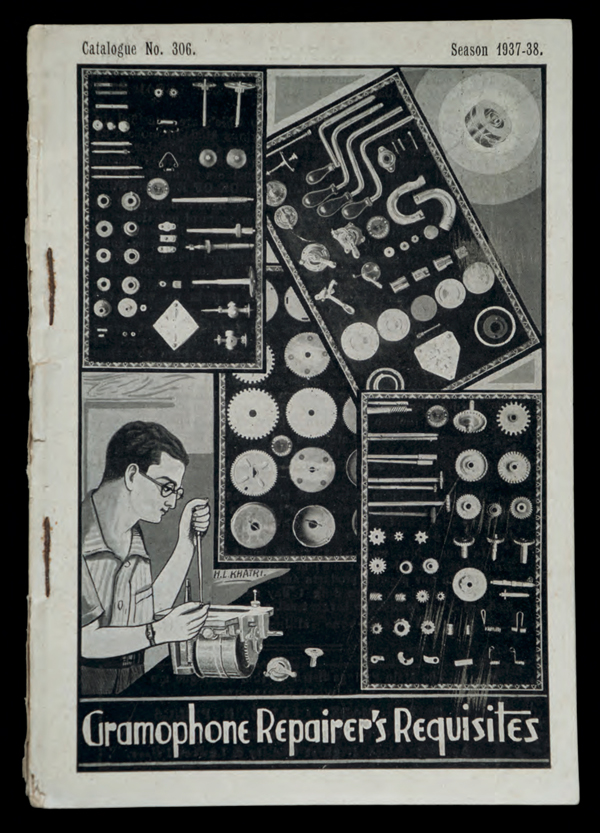

Those looking for an introduction to the vast history of Indian music should seek out a Rough Guide or something. Because ITM consists almost entirely of images—images of moldering stacks of 100-year-old records, crumbling record plants and Victrola stores, collectors poking through their archives, and tons of ephemera—packages of steel styluses, worm-eaten paper sleeves, record catalogs, promo photos, and label upon label—the majority bearing The Gramophone Company’s archetypal catchphrase “His Master’s Voice.”

Which raises a passel of thorny political concerns that are largely unaddressed in Millis’ brief, anecdotal commentary. The British Raj from 1858 to 1947 is pretty much the ne plus ultra of insidious cultural imperialism, and HMV’s wholesale appropriation and repackaging of India’s musical heritage in order to sell it back to its originators for profit (not to mention some modern-day hepcat from the Pacific northwest planting his flag in what amounts to a record-collector-geek El Dorado) triggers uncomfortable connotations of colonialism.

Gramophone Repairer’s Requisites, from Suresh Chandvankar collection, Bombay.

But then, without that imperial intervention we wouldn’t have these recordings. Which is what it’s really all about. Lovely and intriguing as Millis’ photos are, they essentially form a poetic, nostalgia-drenched, sweetly fetishistic backdrop against which the electrifying vitality of the music stands out in greater relief. The 46 selections dating from 1903 to 1949 run the gamut from Koranic recitations to proto-Bollywood theater music, from intricate mathematical constructions to heart-wrenching vocal acrobatics, from rigorous formalities to improvisational revelations.

For my money, the instrumental pieces are the most phenomenal, beginning right out of the gate with a mind-melting rave-up on the vichitra veena (a fretless slide stringed instrument) by the legendary Abdul Aziz Khan, followed immediately by a 1907 solo on jalatharangam—a set of ceramic bowls tuned by filling them with different amounts of water—over what sounds like a harmonium drone. There are devotional songs performed by devadasis (temple dancing girls), a raga played on kazoo, a comedy routine, a rare 1916 recording of a snake charmer’s flute, and a selection of vocal imitations helpfully entitled Sky Lark Squirrel Country Oil Mill Red Bird.

It’s thanks to Millis’ bona fides as a sound artist (as opposed to an academic ethnomusicologist) that this selection has such breadth, depth and idiosyncrasy. There are repeated instances of exquisite timbral subtleties that seem to be collisions of the actual music, the limitations of the recording technology, and the century of entropy that has left sedimentary layers of crackle and hiss—synthesizing to deliver an experience Millis once described as “tuning into a radio station from 10,000 years ago or from a distant universe.” The miracle is that in spite of the displacement in time and space, in spite of the distortion, the genius still comes through loud and clear.

Robert Millis

Indian Talking Machine: 78 RPM Record and Gramophone Collecting on the Sub-Continent

2CD/BOOK

22 by 17 cm; clothbound

244 pages

Sublime Frequencies, USA

0 Comments