Whitney Bedford’s landscapes and oceanic vistas were emotional, elusive, uncommon, sometimes based in story, or sweetly teetering on the verge of collapse. Her relationship to the paintings—and by extension ours—was both dualistic and deeply personal. Precisely drawn renderings anchored her compositions in place with specificity, while gestural, diffuse atmospherics strutted across the armature. In her new suite of mixed-media paintings on view at Vielmetter Los Angeles, Bedford changes things up. The densely detailed, intensely chromatic landscape views in “Reflections on the Anthropocene” are political, semiotic, assertively symbolic and narrative works whose deliberate citations of art history serve as the structures on which to hang not only a discourse of aesthetic agency and modern styles but an incisive commentary on humanity’s oppressive, fetishized, destructive imperialism toward nature.

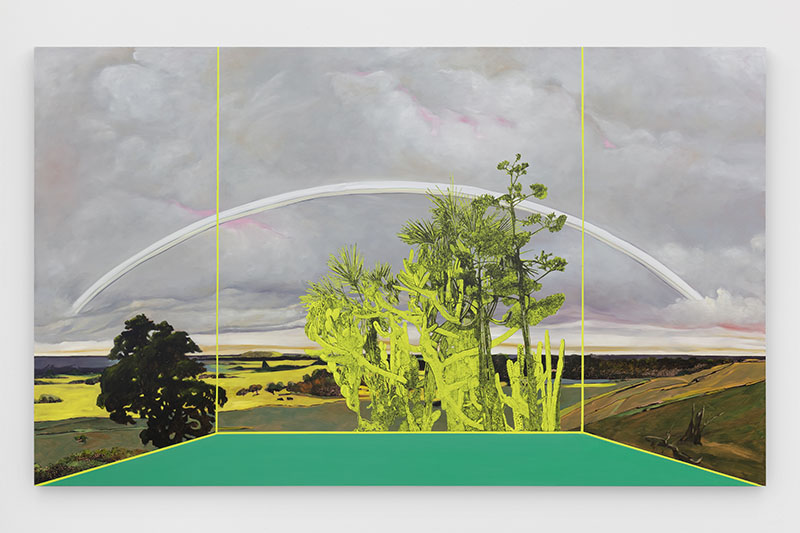

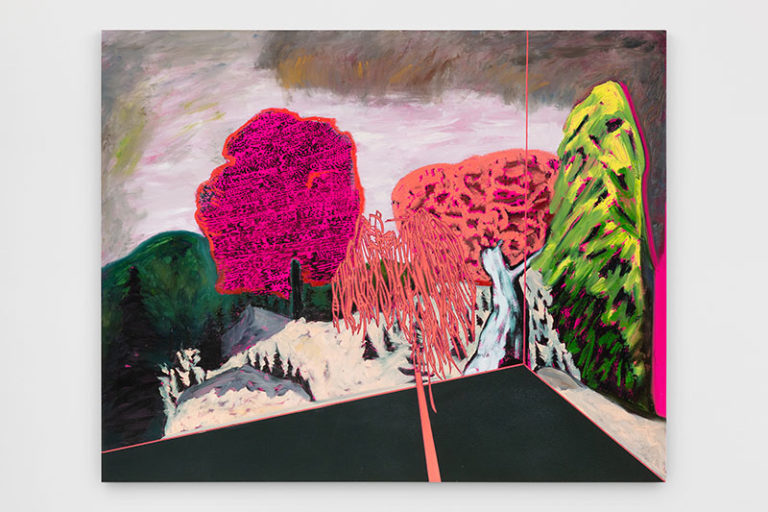

In the balance between creative nuance and activist messaging, these paintings take a perfect middle path, one which creates a fulsome sense of paradox and unease, memory and menace. Each work consists of an interpretive but convincing borrowing of a canonical landscape image of trees, rivers, valleys, clouds, etc.—by such figures as Constable, Sargent and Turner—intruded upon by a schematic architectural glass wall retreating from the picture plane. In the rhomboid foregrounds, between the viewer and the pastoral setting “out there” are Day-Glo succulents that might symbolize drought, and definitely evoke the blasted tree trunks of Thomas Cole. Cole put those lightning-crisped tree corpses into his pictures as a cautionary tale, warning of the impending havoc of industry. And Bedford, too, plants hers in the way, not allowing full access to the pleasures of the past, forcing us to deal with the chemical energy of our dire situation.

Whitney Bedford, Veduta (Avery Landscape), 2019, courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Evan Bedford

In her masterpiece Veduta, (Friedrich/ White Rainbow), 2019, for example, the plane of separation is particularly stark, the gnarled cactus mass particularly opaque, and the vast expanse of idyllic land and sky particularly appealing. In Veduta (For Turner) the palette and brushwork are more gentle, the scale and the scene more intimate, and the paradox more subtle. But at the same time, viewers may associate what was already Turner’s concern with the abstract powers of early industrialism with what’s going on in the series. Bedford’s deft hagiography of natural beauty spotlights the visceral urgency of our present environmental circumstances, but it benefits from her multidextrous juxtapositions across zeitgeists to materialize the message. In the process, she has invented a seductive, witty equation for showing us just how beautiful and all the more so, how absolutely strange, things have gotten.