Master Architects of

Southern California 1920–1940

by Marc Appleton, Stephen Gee

and Bret Parsons

208 pages

Angel City Press

Regarding Paul R. Williams:

A Photographer’s View

by Janna Ireland

224 pages

Angel City Press

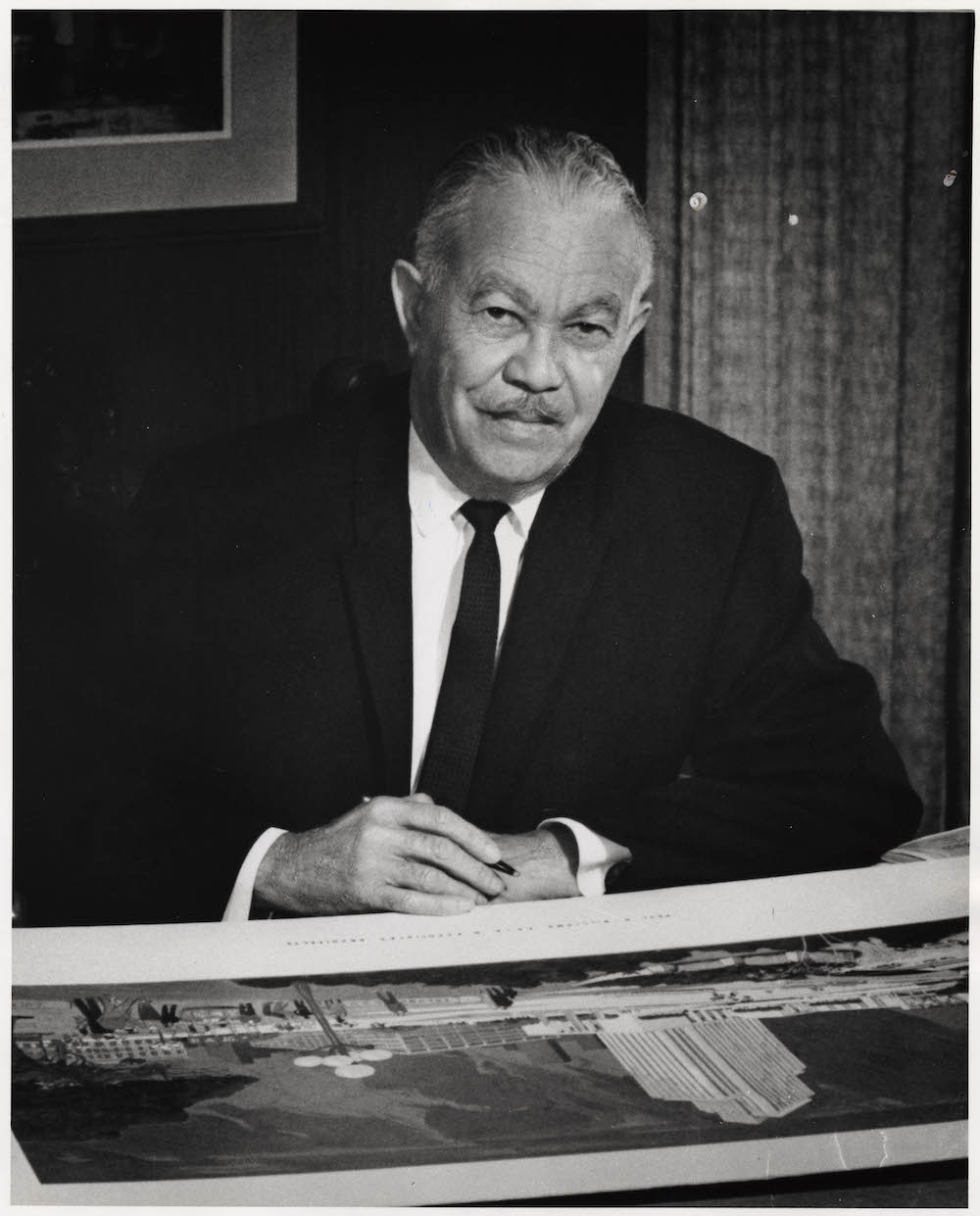

When Paul Revere Williams died in 1980 at the age of 85, he left behind one of the most remarkable legacies in Los Angeles architecture. He not only designed homes so elegant and livable that he was avidly sought after by such celebrities as Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Barbara Stanwyck and Lon Chaney, he also designed institutional and commercial buildings that are with us still such as the Beverly Hills Hotel and the New Hope Baptist Church. When still in his 20s, he was appointed to the city’s first planning commission. In 1923 he was elected to the American Institute of Architects, the first African American admitted.

Two books about the architect have come out recently, both from our own Angel City Press. One is part of the Master Architects of Southern California 1920–1940 series, written by Marc Appleton, Stephen Gee and Bret Parsons and utilizing pages from Architectural Digest magazine when it was based in Los Angeles. The other book is Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, by Janna Ireland, who spent several years photographing the exteriors and interiors of Williams’ extant buildings. If you live in the greater Los Angeles area, you have passed by or walked through one of his buildings—he designed some 3,000 of them, including some in other cities. Unfortunately, a number have been demolished.

Paul R. Williams. From Master Architects of Southern California 1920-1940: Paul R. Williams.

The Master Architects volume is a terrific reference, opening with a well-researched and detailed biography of Williams and his career. Then 30 residential and commercial projects are featured, pages from Architectural Digest supplemented by new editorial material. The vintage pages are on a light tan background, clearly setting them apart from the new material. In most cases specific addresses are left out—that would have be useful for architectural buffs like me, who like to go look at actual buildings.

Both books point out that Williams learned to be adept at many styles—including Tudor, Georgian, Mid-Century—and in both residential and institutional designs. The fact is he had to be, to get enough clients to support his family and his business, and he had ample talent to do so. After working for several well-established architects, he set up his own practice in 1922 and worked hard and long enough to see it flourish. Due to restrictive covenants, he couldn’t live in upscale Hancock Park where he designed many a mansion, as seen in these books. After such covenants were declared unconstitutional, he did build a pretty impressive home in Lafayette Square, in the spare, sleek International style.

Hillside Memorial Park Mausoleum and Al Jolson Shrine, 2019 From Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, page 147.

Ireland was introduced to Williams by Barbara Bestor, one of LA’s leading architects, who suggested this project to her and helped her make contact with several homeowners. As Ireland, who is African American, delved into Williams’ life and work, she saw parallels with her own career, and admired how he faced down the pervasive racial prejudice of his times. For example, he learned to draw upside down, so that he could draw for clients without them having to sit next to him. “When I began my project,” she writes, “this and other stories about Williams’ knack for turning indignities into triumphs intrigued me.”

The photographer uses an artist’s eye in capturing these black-and-white photographs. There are wonderful details of cornices and sweeping staircases, as well as overall shots of the buildings in their settings. The pictures are not arranged chronologically or by style, and one building may pop up in different parts of the book. As a former picture editor, I would have laid this book out differently, but I think there is some visual rhythm to the layout as it is. A more nagging issue is that the mid-tones of the pictures are a bit muddied, which might have been adjusted during proofing and/or using a different paper stock.

Seaview Community, Rancho Palos Verdes, 2018 From Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, page 134.

Both books are very timely. It’s certainly time our knowledge of LA’s architectural history expanded beyond the Case Study houses and what Bestor calls “the modernist orthodoxy.” These books contribute to our understanding and appreciation of a singular talent—a man who helped define the look of our built environment.