Your cart is currently empty!

Category: JULY-AUG 2021

-

From the Editor

July-August, 2021; Volume 15, issue 6

Dear Reader,

It is inexcusable to not be well read, mainly because it’s so easy to fix. Just read more! But who has time? Only recently, when a friend asked what book I was reading, I had to admit that all I’d been reading was art copy. He found that unacceptable and told me how he makes it a priority to set aside time to read every afternoon, in addition to nighttime reading, bathtub reading—he probably even reads while he masturbates!

There are those kind of readers, and then there are readers like me. Then there are the Summer Readers. If I can swing a summer vacation that involves daytime lounging, count me in to catch up on my reading.

Even the well-read read in the summer. So with that in mind, we bring you our Summer Reading issue, where we put together some selections that include book reviews, interviews with writers, profiles on authors, and some prose offerings.

We mixed it up a bit too: Local artist moonlights as art detective novelist (or is it the other way around?)! Fiction LA writer/law professor Xyta Maya Murray says “Art Is Everything,” reviewed by Christopher Michno. Natasha Boyd revisits French filmmaker Eric Rohmer and his Catholic ways. LA artist Tom Knechtel treats us to the tiny world of Pat Sweet and her labor-of-love publishing company where miniature handmade books are created. Bunker Visionist Skot Armstrong reviews the new Dali biography, looking past the kitsch and rediscovering the painting. Max King Cap examines Black grief and reviews the posthumous catalog and exhibition from Okwui Enwezor now up at the New Museum in New York. Staying in New York, Sarah Sargent takes us to The Met for the Alice Neel show. LA skid row photographer Suitcase Joe’s new book gets critiqued by photographer (and Artillery photo columnist) Lara Jo Regan. And our excellent lineup of LA reviews includes Ezrha Jean Black’s take on Umar Rashid’s latest show at Transformative Arts.

Lastly, no worries, we didn’t forget the pandemic. This past year cannot be ignored; we’re all still licking our wounds. Unsurprisingly, as we re-enter the art world, we have noticed a lot of new work that addresses our recent human tragedy. At the same time, there have been rumors that some people are missing the pandemic ways. Regular contributor and poet John Tottenham was one of the first to extol the “pleasures of the plague” in these very pages. In his world, last year was the year that just kept on giving. John takes us on one of his adventures—a jaunt that finds him on an off-track betting and dive-bar excursion. Who knows who might show up sitting beside you in Vegas? We’re always up for a good laugh about the good ‘ole COVID days and glad that Tottenham always delivers.

Ah, those lazy days of summertime—Hop on a bus to Vegas for the weekend, plan an off-the-grid summer in Maine, swim on the shores of Galveston. It’s good to get away …and get into a book.

-

Shoptalk

Return of Art Fairs, Painting is “In,” and What The New Normal Looks LikeThe New Normal

We thought the world would end in fire, or possibly in ice. And now we know it can end with a virus. As a child growing up in Taiwan and then later in the US during the Cold War, I often imagined—and literally dreamed—how the world would end. Earthquakes and nuclear holocaust were my usual Apocalyptic scenarios. I did occasionally imagine a strange, contagious disease, but not one quite like COVID-19 where the entire world would be held hostage, so widespread and for so long.

Now as we slip back into public life, we realize that we have changed, and so has the world we return to. Many people will continue to work from home, in full or in part. Students have gotten trained in online classrooms. As someone who’s been teaching on Zoom, it’s clear that online education can’t match the real-life one, though it can certainly supplement it. Museums and galleries have run virtual exhibitions and presentations, and are now reopening at limited capacity. By the time this is published, they could be at increased or full capacity. However, in the past year programming has undergone a radical shift—with more, deserved attention paid to POC and women artists. The world we return to is not the world we left last March. How could it be? Which changes are to be enduring and systemic remains to be seen.

“Shattered Glass” show at Deitch Projects Painting

Painting is coming back, and in a big way, but the painters being featured are not the ones highlighted in the past. There was the extraordinarily exciting “Shattered Glass” show at Deitch Projects, curated by Melahn Frierson and AJ Girard, with 40 POC artists, many of them young and emerging and based in California. I went on the closing day, and there were a couple hundred people there—the largest event I’d attended in a while. And what an energy, what a charge as the artists mixed happily with family and friends, old and new, mostly masked but not able to keep distances. Girard was giving tours, there was a fashion show, and lots and lots of photos were sent to Instagram.

There was also some excellent painting. La Piedra Negra by Vincent Valdez, was one that stopped you in your tracks: a very large painting of the head of a woman, resting sideways on a rock as if listening to something. Her background is a city on fire or perhaps an especially flaming sunset—hauntingly beautiful and not a little unsettling. There were paintings by the Finley brothers: Kohshin Finley’s monochromatically toned Marque and Tiffany shows a young couple in a quiet moment of tenderness, while Delfin Finley’s Rumination portrays the back of a young man with loops of colored ropes slung over his shoulders—a real tour de force of photorealist painting.

The two-woman show at L.A. Louver with Rebecca Campbell and Heather Gwen Martin was a good pairing, featuring two painters with dramatically divergent aesthetics. I thoroughly enjoyed the first show for Brooklyn-based abstract painter Patricia Treib at Overduin & Co.; her lyrical shapes are part Matisse cut-out and pure whimsy.

Sister Corita Kent’s studio in Hollywood Comings and Goings

Galleries continue playing musical chairs. Luna Anaïs has moved from a downtown space to Tinflats in Frogtown—and launched with an opening party drawing a lively, multi-generational crowd for a show featuring Gloria Gem Sánchez and Tidawhitney Lek. Owner Anna Bagirov (full disclosure: Bagirov also helps Artillery with its marketing) is very happy with the bigger space, though it’s leased on a temporary basis, so who knows how long they will be there.

Von Lintel has made another move. They were in Culver City for years, then moved to DTLA, and on May 15 reopened in Bergamot Station with a show by Christiane Feser. “Sadly downtown has suffered immensely from the pandemic,” said Von Lintel via email. “Closed store fronts and countless homeless seem to dominate the scene. I decided that easy access and parking were important for this next post-COVID phase, all of which Bergamot Station in Santa Monica offers.”

Earlier that month, on May 1, I visited Bergamot for a group show opening at Craig Krull, and it was heartening to see how many people showed up. The reception was out in the parking lot, and it was like homecoming week, with lots of longtime-no-see greetings, and people announcing, “I’m fully vaxxed, too.” Even so, we mostly kept our masks on when not drinking.

In recent years Bergamot has been gutted by departures and the uncertainly of development. I recall that at one time there were two competing projects, one that included a hotel and other retail, but right now nothing seems to be underway. There are quite a few empty spaces, and it would be great if more galleries could find their way there.

Hauser & Wirth is adding yet another gallery to its well-feathered cap, with a second LA location. Their current spot in a former flour factory in DTLA is already an art destination, and now they’ve leased a new space at 8980 Santa Monica Blvd. in West Hollywood, scheduled to open fall 2022. The 10,800-square-foot space will be designed by Annabelle Selldorf of Selldorf Architects, designer of their DTLA location. And yes, there will be a restaurant.

Something that is not coming or going, but staying, is Sister Corita Kent’s studio in Hollywood, which she used for making her activist art and teaching from 1960 through ’68. It’s now in private hands, and the owners were planning to tear it down for a parking lot. (Hmm, remind you of a certain Joni Mitchell song?) On June 2, the LA City Council voted unanimously to approve the studio as a Historic-Cultural Monument, thus saving it from demolition. Eventually, the Corita Art Center, which started the petition to save the building, hopes that it can be made into a cultural center. It is plain, even drab, in appearance, but it is historical, and a very small percentage of sites related to women or POC have achieved Historic-Cultural Monument status. Kudos to the preservationists!

LA Art Show—coming soon! Art Fairs Return

And they’re baaack! The LA Art Show had to back out of its usual January slot, but it has rescheduled itself into the LA Convention Center for July 29–August 1. They’re billing a “European Pavilion,” which I’m looking forward to seeing. https://www.laartshow.com/

The Felix Art Fair is also returning that same weekend, and to their old venue, the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. This time they’re taking up only the first floor “cabanas” around the pool and focusing on just 29 Los Angeles galleries. Get your tickets early for this one—it’s always crowded. https://felixfair.com/

-

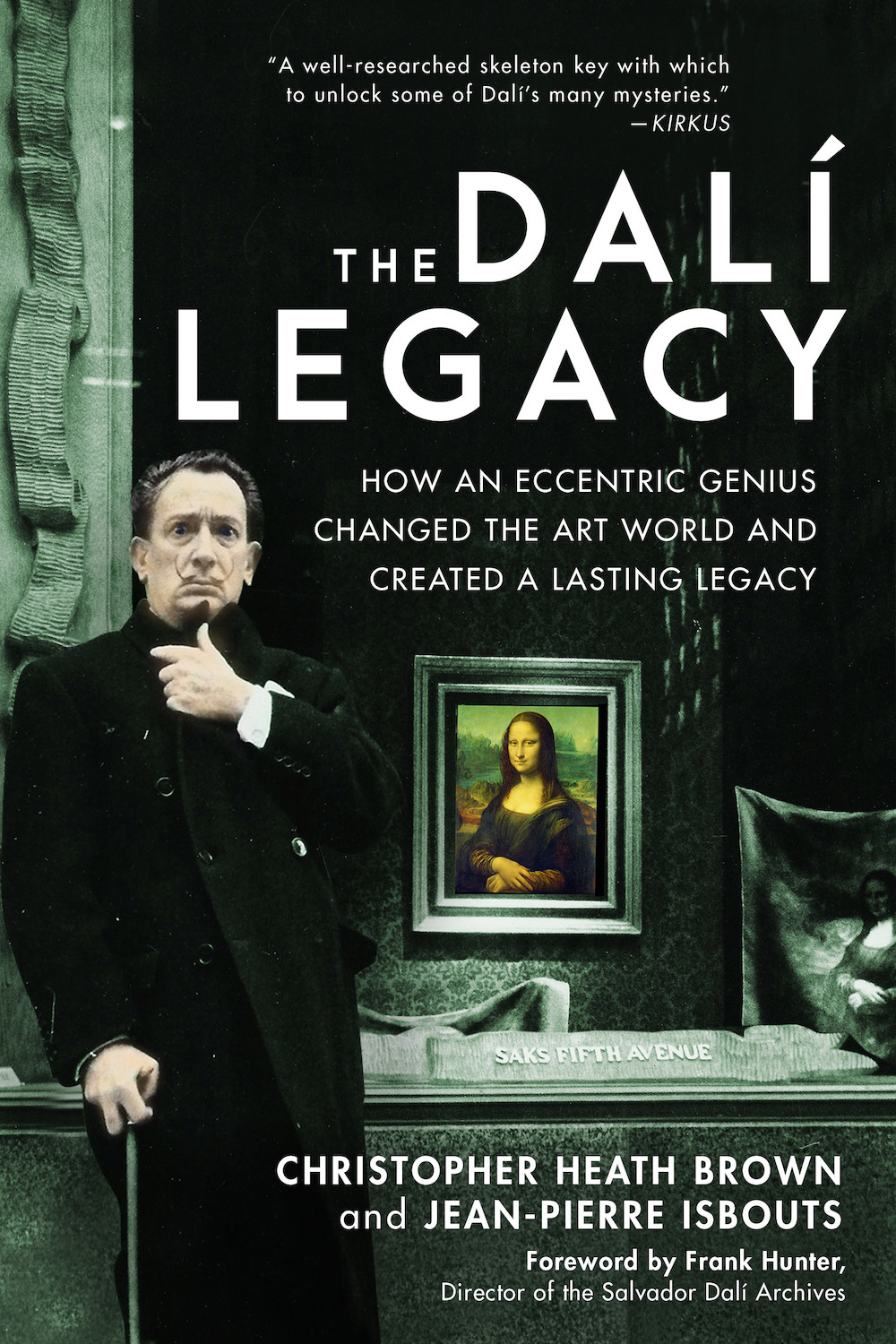

THE PERSISTENCE OF DALI

“The Dali Legacy” By Christopher Heath Brown and Jean-Pierre IsboutsSalvador Dali has always had a troubled relationship with the Art World. His work embraced figurative representation during a century where deconstruction and reinvention were the mode du jour. His theatrics often upstaged his considerable talent. The amount of energy he expended playing the role of eccentric artist often distracted critics from the solid theories and concepts that underlie his work. By the final years, when he was signing blank paper to raise cash, “serious” collectors eschewed his work. Part of the reason for this was his popularity. No matter how hard the gatekeepers tried to keep him out of the canon, his popularity with the general public has never waned. There are museums in Florida and Spain dedicated solely to his work, and they rarely suffer a shortage of visitors. A new book, The Dali Legacy, untangles the chaos of obfuscation and myth from the solid underpinnings of concept and technique. This might be the first book to focus on Dali the painter and theorist.

Book cover. The book is chronological. It starts out with a good overview of the world that shaped him. One bit of great detective work involves figuring out which paintings he might have seen at an early age, based on where he grew up. Using the museums in the area as a guide, it is possible to determine what he might have been exposed to. The authors also do a good job of explaining what a printed painting would have looked like at the time (black-and-white approximations), and how startling it would have been to see a crisp version in full color. As we gain a clearer understanding of the art that shaped Dali’s outlook, we are afforded a better understanding of why he approached certain techniques and subjects as he did. When he heads off to art school, he is a bit furious that nobody is teaching old master techniques.

Salvador Dalí, Corpus Hypercubus, c. 1954

© 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights

Society. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image

source: Art Resource, NYAs Dali strikes out on his own as an artist, we get a sense of how his approach was viewed by his peers. He was embraced by the surrealists before he was expelled for his politics, which were mostly the politics of convenience. Though he voiced a fascination with Hitler as a charismatic figure, he never expressed Nazi sympathies. Most of the pro-Franco stuff was the result of wanting to keep his studio in Spain. Given that the Met had to offer a disclaimer on the Stein art collection because of Nazi collaboration, he was perhaps less alone in these gray areas than was previously assumed.

Salvador Dalí, Study for The Skull of Zurbarán, 1955

© 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights

Society. Photo credit: Chris Brown CollectionBy the time Dali was 30 he had already produced his most known art work, The Persistence of Memory (1931) using his Paranoid-Critical Method. Most of what we think of as the classic Dali nightmare work was produced during this period. This is usually where Dali biographies begin to lose their focus. By now he was a famous eccentric, with loads of anecdotes and accompanying salacious gossip. The authors treat his 1939 World’s Fair pavilion as a work of art, but otherwise tighten the focus for the rest of the book to his evolution as a painter. This is a wise choice, as biographers often get weighed down by his other exploits. He wrote books and the libretto for an opera, designed furniture, jewelry and movie scenery, and barreled through his remaining years in the form of one long performance piece.

The book is divided into sections based on what “periods” followed in Dali’s evolution as a painter. After he abandoned the Paranoid-Critical Method, he became rapt by the atomic age. A huge motif in the work of this period was based on the scientific concept that atoms don’t actually touch. While he was exploring atomic structure, he became fascinated by the Ben-Day printer dots (over a decade before Lichtenstein).

Salvador Dalí, The Skull of Zurbarán, 1956

© 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights

Society. Photo credit: Robert Descharnes / © photo Descharnes &

Descharnes sarFollowing that was his mystical/religious period, where he painted some of his largest and most compositionally complex paintings. In this section of the book, we get an in-depth look at Dali’s fascination with da Vinci’s concepts. This book made news recently because of the inclusion of preparatory sketches for some of his geometrically complex compositions. The authors conclude that his last great painting was finished in 1972. He lived another 16 years.

When an artist is this publicity-conscious and aggressively outré, it is easy to conclude that he is making up for a lack of vision and talent. But, by stripping the focus to his painting, it is easy to find much that is admirable.

-

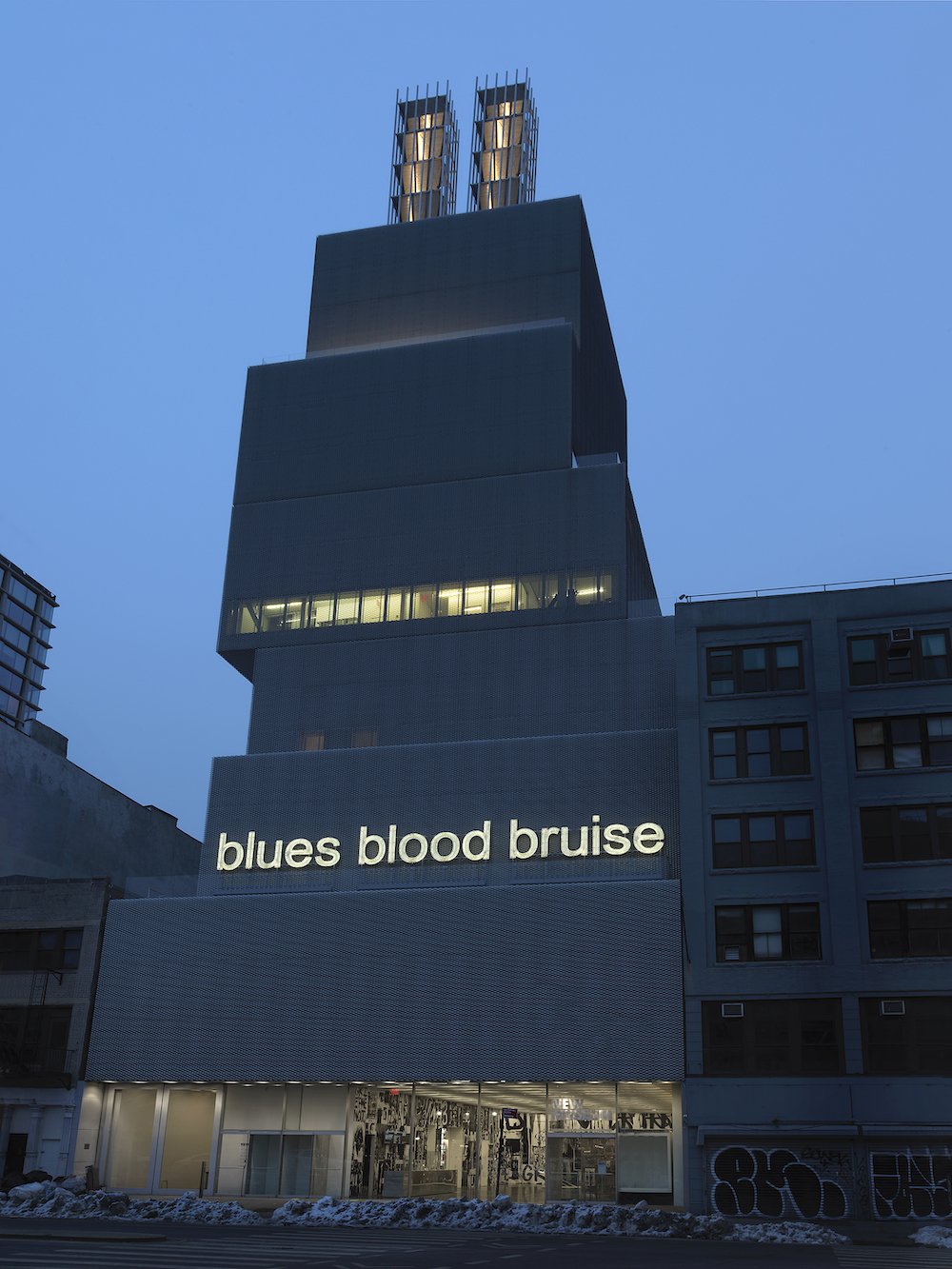

Black Grief Examined at New Museum, NY

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” By Okwui EnwezorGrief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, 2020

By Okwui Enwezor

264 pages

Phaidon/New Museum, New York

In a pivotal scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s film The Godfather a Mafia don grieves over the body of his dead son. “Look how they massacred my boy,” the weeping father intones, and the audience grieves with him. A worldwide audience is moved by the pantomime death of a handsome movie actor.

Another dead son, this one truly dead and made so just a few years after the theatrical death, is viewed in an open coffin. He is just a boy, and he is disfigured, gruesomely distorted. He is missing an eye, he is swollen, and he is, was, real. Upon the perpetrators there is no comeuppance visited. There is no justice.

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni In Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America—a piercing title that recalls the Reagan era—the late author and curator Okwui Enwezor had envisioned an exhibition where writers and artists excavate, examine and enliven the antithetic of Black and America. His death at age 55 prevented his completion of the project but it has been dutifully and beautifully realized by Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon and Mark Nash.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, THE FULL SEVERITY OF COMPASSION, 2019 in “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. The book by Phaidon and exhibition at the New Museum feature the work of essayists and artists whose work is both moving and haunting. Considering the historical similarities between Black deaths in the antique and the contemporary, Saidiya Hartman, in her essay, Dead Book Remains, conflates the horrors visited on past and present Black bodies as being something to be expected; that while their labor may have value their personhood does not. In My Soul Looks Back in Wonder Naomi Beckwith records the evolving status of images of negritude, from persecution to resistance, and specifies how the co-option of Black pain as seen in the Whitney Biennial’s choice of artist Dana Shutz’ Open Casket (2016) painting of the decomposed Emmett Till was so cack-handedly considered; a throwback souvenir for unreconstructed white folks, like baseball manager John McGraw’s lynching rope souvenir, or dreadlocked ski-bums in Vail.

The artworks featured include The Full Severity of Compassion (2019) by Tiona Nekkia McClodden, a fully blackened cattle squeeze chute, suggestive of bodily coercion, experimentation and consumption. Similarly haunting is Drainer (2018) by Julia Phillips, a ceramic cast of a woman’s torso suspended above a concrete shower drain, a peculiar bodily dissection of unknown or willfully dismissed history.

Julia Phillips, Drainer, 2018 in “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Many of the artists included are so widely known that their contributions become less powerful. Celebrity transforms their work into spectacle, clouding the visceral bite they might otherwise convey. The majority of works and essays, however, reach deeply into our sensibilities, insisting that we either embrace or dismiss, to vehemently choose sides.

Yet the rise of righteous protest and demand versus the naked and eager retaliation that it faces has not prefigured a concluding détente but a death spiral of the republic, suggesting that any hope of equity will ultimately devolve into a tense and simmering stalemate.

-

Eric Rohmer’s Beach Readers

The Catholic WayNo one ever “works” in Eric Rohmer’s movies—but they do read. By necessity, Rohmer’s setting is one of leisure, whether it’s the beaches of Biarritz or the shores of the French Riviera. His characters need ample time to read and to daydream, and for ennui, disturbed by the intruding object of desire, to ripen into an obsessive devotion.

L’amour l’apres-midi (still), 1972 They are not attentive readers. Their attention is elsewhere, with the aforementioned object of desire. They pick up their reading to escape their own feelings, or, just as often, so that they can cruise over the tops of their books. Their conversation is equally evasive. While, as Rohmer has said in a 1971 Film Quarterly interview, his characters “like to bring their motives, the reasons for their actions, into the open, they try to analyze, they are not people who act without thinking about what they are doing…” prolixity makes them expert rationalizers and dissemblers. Books are the perfect accessory for such characters, who in literary conversation can speak of themselves without the stakes of a confession. Only for one moment of exquisite truth do they reveal themselves, every second since the opening credits pushing towards the immense force of will and pressure of circumstance required to make the interior and the exterior meet. Rohmer, the consummate Catholic, makes films about people acting in bad faith.

La collectionneuse (still), 1967 Rohmer began his creative life writing short stories before making a decisive turn towards cinema. In “Celluloid and Marble,” an essay series for the Cahiers du Cinema (1966), Rohmer argues that literature is “a mirror which reflects the world, but which distorts it as well.” It was film that was “the last refuge of poetry” and the only art in which metaphor could arise “naturally and spontaneously.” For example, the lashing copse of trees where the unhappy Delphine finds herself choking back tears in Le Rayon Vert (1986), is not just pathetic fallacy; the trees, the wind, were both real. If literature suffers from a kind of verticality of information, wherein everything comes from the singular voice of the author, the camera allows for the symbolic and the real to exist on the same horizontal plane. Despite the neurotic isolation of his characters, the world is very present in his movies. Les Amours d’Astrée et de Céladon (2007), his final film and the sweetest, might be the windiest movie I’ve ever seen. It is as if he threw all the doors and windows open to invite whatever poetry the breeze might carry. All his movies share the same light, airy simplicity. His longtime cameraman Néstor Almendros described his method thusly: “His criterion is that if the image portrays the characters simply, and as close to real life as possible, they will be interesting.” (“La Collectionneuse: Marking Time” 2006) Hence the willingness to film his protagonists sitting and reading in the first place. Who else has the time?

La collectionneuse (still), 1967 Simone Weil, a fellow Catholic of the modern period, said that beauty is often the first way to God: it is a lesson in his remoteness. Something that is beautiful is whole; it wants nothing from us, and thus is a kind of tease as well as a kind of truth. Rohmer’s readers, likewise, languish in a world of resounding beauty that intensifies their own frustrated desire. In Le Genou de Claire (1970), for instance, protagonist Gerome strolls through an actual rose garden while considering his erotic fixation on the budding teenage sisters Claire and Laura. To the precise degree that Rohmer’s characters attempt to hide their yearning, Rohmer’s camera entraps them in it. Maybe that’s why they are so eager to hide their faces in their books.

-

EVERYBODY WANTS SOME By John Tottenham

Tinnitus hissed through the music, the laughter, the static. It wasn’t crowded in there, but it was loud. Two women at the bar, a few feet away, were engaged in a conversation that consisted of whooping and screeching at the top of their lungs in response to every exchange that passed between them, with no concern that others within such close proximity might not want to have their eardrums battered by gales of exaggerated merriment. In the middle of the room, standing around a small circular table, a group of beer-swilling men yelled at a ballgame that was broadcast on various TVs stationed around the walls, so that one’s gaze was never obliged to rest on anything motionless. Screaming screens, screaming people. It was six o’clock and they were letting off steam; it was their domain, and I was just a stranger—sitting, drinking, thinking, or trying not to—a silent island amid raucous camaraderie.

I didn’t know what else to do until it was time to walk back to the hotel and retire to my room—out of which many dead bodies must have been carried during the hotel’s storied 80-year history—with the vertical red neon GAMBLING sign flashing on and off directly outside the window.

The game ended, the young women left, the noise subsided, and I could hear the conversation to my immediate left.

“I was in California hunting for meteorites…” a hairy man in bib overalls was saying to his mostly silent companion. “On the way back, I stopped in at the Cherry Patch. Great place… the girls were wandering around topless in the parking lot…”

It was refreshing to be drinking in a bar for the first time in six months. Where I came from they were all closed, owing to COVID. I sat there, folding softly into medicinal warmth, savoring the increasingly perceptible glow.

A tall, slim middle-aged man with long silver hair walked in and took the seat directly to my right. He wore rings on his fingers, several cigars poked out of his breast pocket, and he carried a book. The prospect of somebody reading a book at the bar cheered me. He lit a cigar and ordered a cocktail.

A few minutes later, he was joined by a man with dyed jet-black hair, who wore a Black Flag T-shirt that exposed unusually muscular arms for somebody of his advanced age. He sat down on the other side of the Silver Fox, placed four books on the counter—all crime-related, with red-on-black lettering on their spines—lit a cigarette and ordered a cocktail.

Something that sounded like John Lee Hooker, ramped up and crassified almost beyond recognition, blasted out of the jukebox. The title of the song, “Hot For Teacher,” was familiar but I had never heard it before, and had no desire to ever hear it again.

Stray words, an occasional sentence, scraps of conversation drifted over in my direction. “… He was in a couple of Jarmusch movies,” said the Silver Fox in a gravelly accent, dragging out that cherished word, “Mooo-vies,” with salacious relish. “Overrated… coasting… he’s been sleepwalking for years… always the same role…” Clearly they were talking about Bill Murray.

His companion mostly just nodded or muttered in agreement while idly playing video poker in a manner that suggested it was merely a pleasant way to throw away disposable time and income. Looking at him more closely, I recognized him as a well-known director, one of the few American filmmakers whose work stirred interest on the strength of his name. A quick search on my phone confirmed this impression. What was he doing in such a nondescript watering hole? Enjoying some sort of friendly, alcoholic business meeting with a screenwriter, by the looks of things, hence the exchange of books.

“…You can get a decent lunch there,” the overalled dude to my left was saying. “It’s cheaper than a date and you know what you’re getting for your money.” In the bar mirror I took a closer look at the speaker. Gray hair sprouted from his sagging chin, beneath which a surgical mask dangled apathetically as he puffed on a generic cigarette.

Social distancing: forget it. Looking down the bar, one head after another was bent over the individual video poker screens that lay at slightly mounted angles on the counter, providing booze-weakened patrons with the convenient temptation of digitized games of chance. Inglorious clouds of smoke, released from potentially diseased lungs, floated through the airless room. This mob weren’t drinking the COVID Kool-Aid. Lockdown… mockdown… meltdown.

“Can’t you see me standing there with my back against the record machine…” Another blustering Van Halen song tore out of the jukebox—shrill, digitally distorted, disrupting the desired quietude. As David Lee Roth said, a jukebox was a “record machine.” It should contain a limited number of selections, preferably 45 rpm discs. That’s what gave each one its own character. Nobody would ever again remark that a “great jukebox” could be found in a particular place now that these ugly little wall-mounted contraptions had taken over, offering inexhaustible options and taking all the pleasure out of the experience.

“Nobody knows anything and I know as much as anybody else,” said the Silver Fox as he took a drag on his cigar, holding it between thumb and forefinger. It was a good line; I might use it. I looked over at them from time to time but not one glance was cast in my direction. Perhaps they had run out of curiosity; they didn’t need it anymore. Why would they? They had it made… they had made it. They didn’t give a fuck about some loser sitting in a bar.

Photo by John Tottenham I ordered another tequila and soda. If I got drunk I could fall asleep immediately upon returning to the hotel, wake up early, breakfast sumptuously in the hotel restaurant and be comfortably situated in time for the first Belmont race at 10 in the morning, spend a pleasurable and profitable day betting in the sportsbook—making amends for today’s afternoon of crushing and wallet-airing near-misses that I was now trying to avoid analyzing and agonizing over—then walk a mile down the deserted streets that gently seethed with a seductively malevolent stillness, back to this unassuming neighborhood tavern situated in a semi-abandoned 1960s shopping center on a wide commercial boulevard.

These were the true boulevards of broken dreams, pulsating with a combustible menace, night and day. Broken dreams and broken people: broken-down gamblers, sore winners, ruined beauties, years of wretched excess scraped into their features— “beated and chopped with tanned antiquity,” as the Bard said; stripped by capitalism of their dignity and dumped onto the sidewalks and vacant lots of this city, among the undernourished and the electrified. There was always some lone figure skulking around in the distance across a vast expanse of empty parking lots and demolished motels. But the homeless were harmless. The people one had to worry about were secure in their gated communities. Yes, I could have a few drinks, and repeat the process tomorrow. It was a delightful routine.

“I showed up in the afternoon and there were only two girls in the lineup. Neither of them were hot. All the hot girls were still sleeping,” the bib-overalled whoremonger to my left was still rhapsodizing about the joys of the Cherry Patch.

Why leave? I had already gambled my mood away. Elsewhere, on the streets, in the casinos, or alone in a hotel room, ruinous brooding could easily become corrosive. Here, amid the fellowship of mostly silent strangers, warmed by the proximity of each other’s distance, it could be contained and transformed into something benign.

At eight o’clock the bartenders switched shifts. It was hard to distinguish between them: they were both blonde, generously proportioned and middle-aged, and unlike the patrons, they wore masks.

“There you go, dear,” said the new bartender, placing my cocktail in front of me. I was touched that she called me “dear.”

More digital bombast burst forth from the so-called jukebox. A metal version of “Where Have All The Good Times Gone.” It was a good question and Van Halen’s crass rendition of the old Kinks song, stripped of all subtlety, didn’t provide the answer.

“It’s great to have those memories,” the Silver Fox was saying, as he spluttered over his cigar. Naturally, I didn’t know what memories he was referring to, but I knew what he meant. He said something about “North Beach,” so I assumed that the memories in question took place in San Francisco, and judging by the looks of him now the halcyon days of his youth would have been the 1970s.

Yes, I knew what he meant. I also looked back wistfully on my incandescent youth. But I wondered if those days might be even richer in retrospect if I had done more with my life since then. It seemed that the sweetness of those times would be sharpened by contrast if one’s fortunes had shifted significantly during the intervening years.

These two men, secure in their status as successful artists, were able to cast a sentimental eye over their early struggles from the comfortable vantage point of subsequent worldly success. The heroic phase was long past, the mountains had been climbed and their legacies were secure; they could take it easy now, smoke a good cigar, sip fine liquor, and play video poker. They had earned it, and nobody could deny them the satisfactions of their reward. This much I presumptuously gleaned from a few minutes of mildly inebriated observation. For all I really knew, they could have led miserable existences of debt, divorce and creative frustration, but on a bigger scale than that with which I was overly familiar.

“It wasn’t the best blow-job I ever had but it was sensitive… she complained when I slapped her ass,” the whoremonger was saying.

Looking up, I saw Eddie Van Halen’s face flashing across one of the TV screens, cutting to a newscaster looking sad, and the penny dropped. The crash course in Van Halen suddenly made sense. Now that he was gone, I had a newfound appreciation of his music and felt guilty about my earlier abhorrence. The poor guy was probably younger than the men on my right, who were still freely smoking and drinking. Their books lay there unopened. They would be opened later and assessed for movie adaptation potential.

The door opened and a warm desert wind blew into the room…

-

The Miniature Books of Pat Sweet

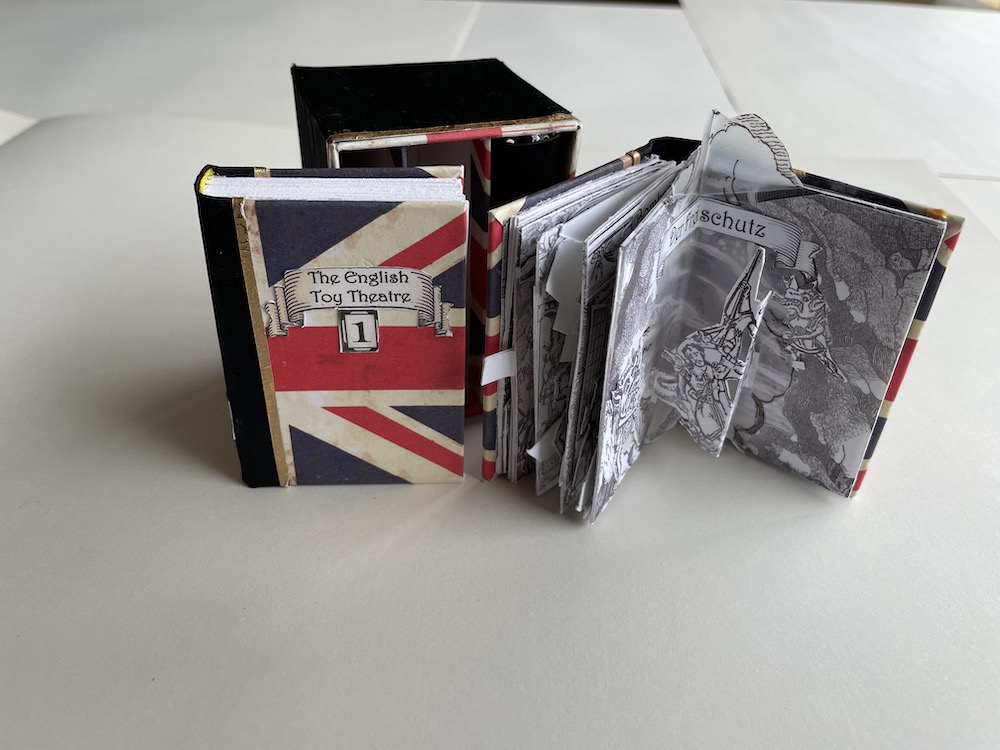

MANY SECRETS & MANY ANSWERSRooting through used bookstores in Berlin in 2006, I discovered the minibuchs published in East Germany during the ’70s and ’80s. These tiny volumes, with their exquisite bindings and photos of happy children giving floral bouquets to returning cosmonauts, launched me into collecting miniature books. Over time I narrowed my focus to handmade books, books by artists and books that played with the idea of what a book could be.

The world of miniature book publishing draws artists who recognize an opportunity to explore the book’s possibilities as an object and conveyer of what a book might mean. With full-size books, the costs of production constrain creativity and unusual solutions. But presses like REM Miniatures and Juniper Von Phitzer, along with individual artists such as Alexis Smith, Nancy Jackson and Candice Lin, have exploited the freedom afforded by small scale and low production overhead to create wildly imaginative miniature books that capture and beguile us with the emotional magic felt when we first began handling and reading books. Recently this was explored in “TOMES,” a 2019 show devoted to artists’ books of all sizes, at the Williamson Gallery at ArtCenter College in Pasadena. In the same year, the possibilities for extended creative explorations afforded by the miniature was seen in “Dreamhouse Vs. Punk House!,” the invitational group show staged by Kristen Calabrese and Josh Aster in three astonishing dollhouses filled with a compendium of artwork across all disciplines.

Given the heightened interest in this form and my own collecting, it was only a matter of time before I discovered Pat Sweet and her publishing enterprise, Bo Press, operating out of Riverside, California.

Born in Brattleboro, Vermont, and growing up in Keyser, West Virginia, Sweet studied at Potomac State College and West Virginia University before earning her MFA in stage design from Southern Methodist University. Joining the theater department at the University of California Riverside in the ’90s, she honed her skills at devising inventive solutions to individual problems (e.g. creating a coat that could be removed, turned inside out, upside down and backwards to become a suit of armor).

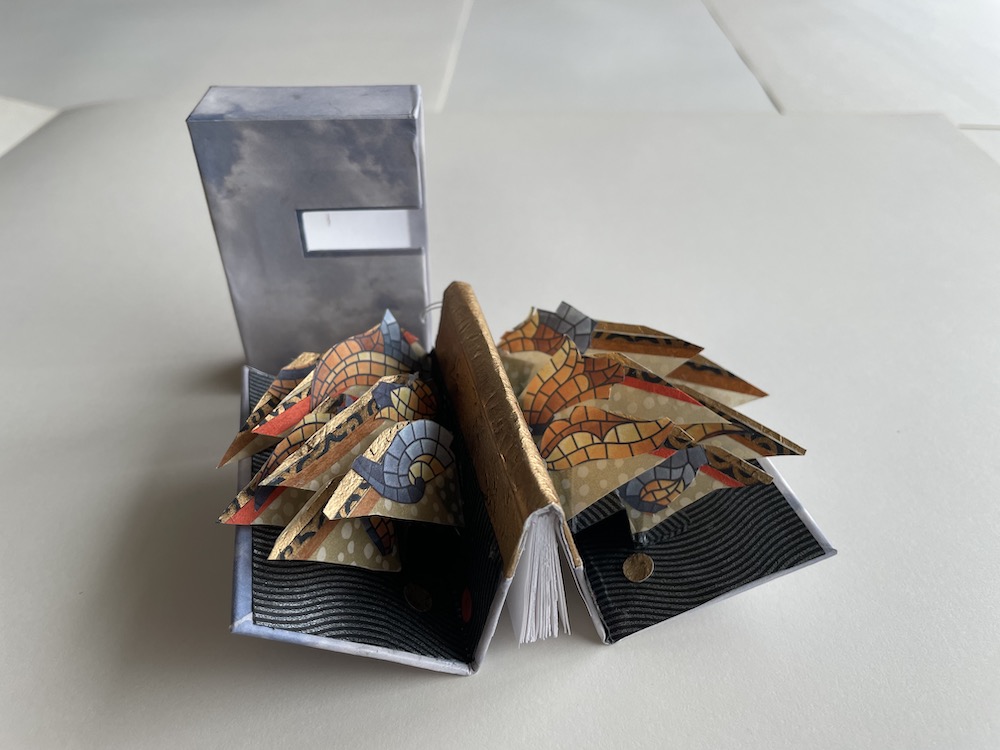

The Windhover, by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Bo Press, 2017. 2 ¾ x 1 ¾ in. The genesis of her oeuvre dawned in a dollhouse she built featuring an extravagant library, complete with spiral staircase (“The hardest thing I’ve ever made, bar none.”). Setting to work creating miniature books to fill the Lilliputian shelves, she found herself caught up in the excitement of creating not just tiny blank volumes but finished books that she would actually want to take down and read. Eventually she started the Bo Press website in 2007 (named for a beloved dog), and began making her books available to collectors, who have kept her busy ever since.

Sweet has pursued a highly idiosyncratic program, publishing not what she thought might sell but what interests her. However, this hardly indicates a parochial restriction of topics. In the first year alone, the content of books published by Bo Press included texts by John Webster, Shakespeare and Thackeray, as well as books on fans and corsets, geometry, beetle species, a listing of sightings of flying carpets, the imaginary Latin used by printers and a re-creation of the map used by the Bellman in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark. The consistent interest in creating portfolios of maps is a touchstone unique to Bo Press. Over the years, Sweet has published map portfolios that detail Napoleon’s retreat, the Nile, the Silk Road, the various kingdoms of Gulliver’s travels, the fictional town in Trollope’s Barsetshire, the map used by Phineas Fogg, and the imaginary world of Eirie, among others. This highly particular path goes a long way toward explaining why the publications of Bo Press display such variety and wit and avoid the uniformity of other press’ efforts.

Sweet quotes Archibald MacLeish: “A poem should embody what it indicates.” Thus, when opened, This is Not a Book reveals a smaller book nestled inside, a volume containing mock-ups of the covers of fictional books that only exist as references in novels. (The Argentinian writer, Jorge Luis Borges, would have loved it.) The Windhover (2017) explores how a book’s construction moves meaning into the poetic realm. Based on a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins about a falcon, The Windhover physically opens in two directions. Opened as a traditional book, the poem is disclosed along with images of wings and feathers. But when opened from the other side, an abstract architecture unfolds and extends itself, like wings expanding out of the book’s binding.

Oscar Wilde’s reply when asked the meaning of one of his fairy tales was: “I did not start with an idea and clothe it in form, but began with a form and strove to make it beautiful enough to have many secrets, and many answers.” Sweet’s books contain secrets, marvels, enthusiasms, questions and wonders—all qualities we thirst for as we navigate the strange times in which we find ourselves.

N.B.—In full disclosure, I have written the texts and painted original illustrations for one of Pat’s recent spectacles, a three-volume history of the English Toy Theatre, with a volume of pop-up scenes from the 19th-century English stage, and a complete theater with pantomime in progress, which unfolds out of a portfolio. (Look for my cat, Nino, and a portrait of my late husband, Robert Baruch, in the stage proscenium.)

For more info: https://www.bopressminiaturebooks.com/

-

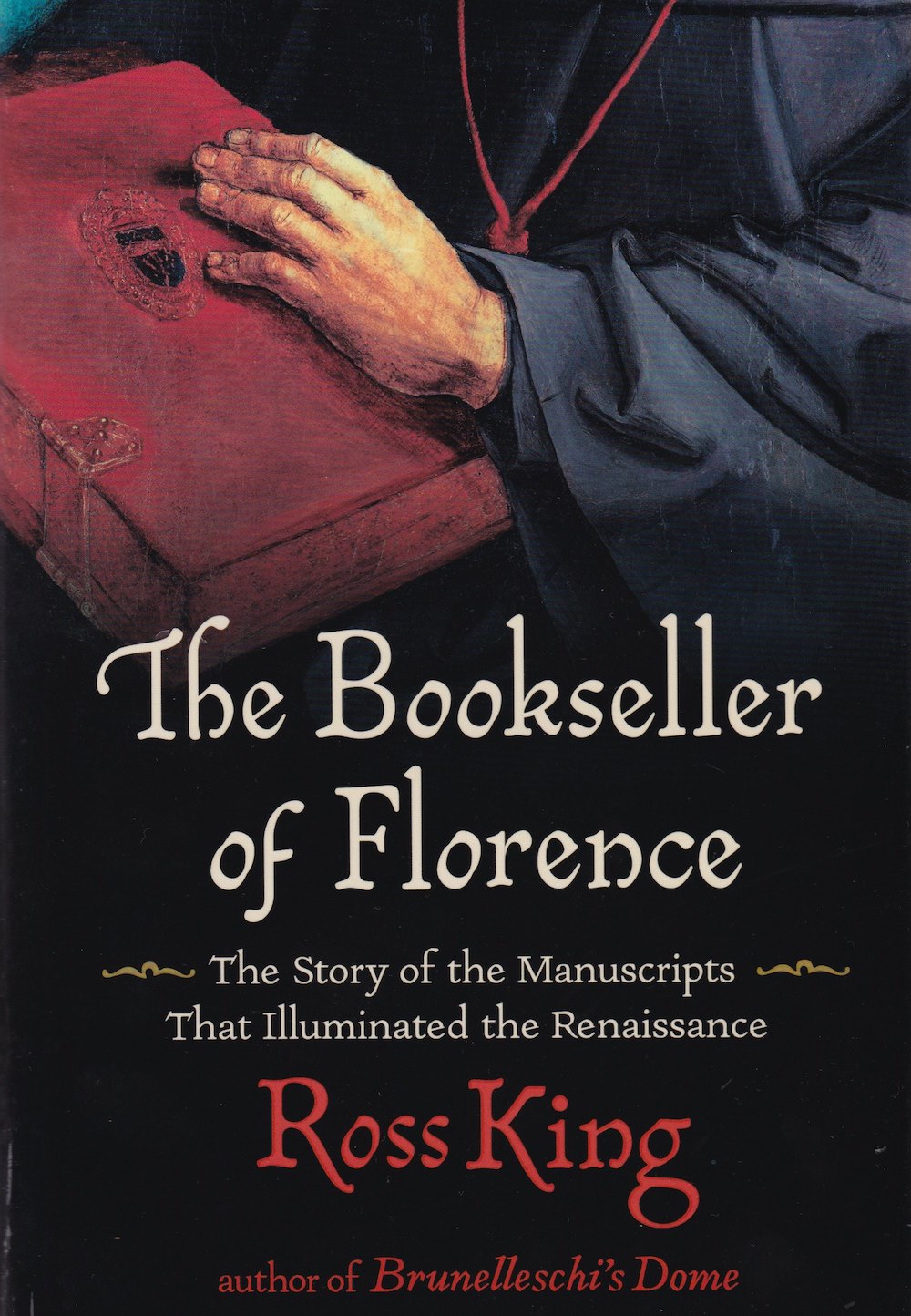

Renaissance Reader

The Bookseller of Florence By Ross KingThe Bookseller of Florence: The Story of the Manuscripts That Illuminated the Renaissance

By Ross King

496 pages

Atlantic Monthly Press

“All evil is born from ignorance. Yet writers have

illuminated the world, chasing away the darkness.”—Vespasiano da Bisticci

Ross King has published several fastidiously researched and precisely articulated books of Renaissance art history. His Brunelleschi’s Dome, a tiny volume tracing the construction of the largest dome since Ancient Rome, became a runaway bestseller in 2013. That volume followed his books about Michelangelo (2002), Machiavelli (2009) and Leonardo (2012). King’s oeuvre is beautifully crafted and clearly conceived, belying all the stereotypes about dense, pretentious art writing.

His newest production, The Bookseller of Florence, focuses on manuscript publisher and distributor Vespasiano da Bisticci (1421–1498). Vespasiano’s career straddled the explosive increase of manuscript production and the world-changing introduction of printed books during the quattrocento.

King introduces his readers to an astonishing array of collectors: popes and sultans, merchants and mercenaries, dukes, bankers, scholars and priests. He also traces the intense power struggles—many of which ended in warfare—that tormented the early Renaissance. My only criticism of the book is that King refers to so many historic figures that it is sometimes difficult to discern who is what and when.

One of the key characters we meet is Johannes Gutenberg, who is credited with inventing the movable-type printing press in 1440. (In fact, such devices actually appeared in Asia centuries earlier: The Koreans had bronze-cast movable type by 1200.) King maps the spread of printing presses across Europe. The first printing press in Florence opened in 1471. Five years later, Venice had 18 printers. By 1500, there were 255 presses operating in Europe. Between 1454 and 1500, over 12.5 million printed books appeared on the continent.

Iean Guttenberg, Inventeur / de l’Imprimerie; illustration extracted from Andre Thevet’s ‘Pourtraits et Vies des Hommes Illustres,’1584. ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Florence is central to King’s story, in part because it had such a high literacy rate: Almost seven in every 10 adults—including female adults—could read. In contrast, most other European cities had literacy rates of less than 25 percent. Largely because of the rediscovery and re-valuation of books by ancient writers like Plato and Aristotle, Florence became the center of the revival of antiquity that led to the “revolution in knowledge” we call the Renaissance. One scholar argued that the recovery and translation of Plato into Latin was “the most important achievement of 15th-century scholarship.” Another called Florence “Athens on the Arno.”

Vespasiano and his clients sought to translate great works from the ancients in order to create “a safer and more stable society.” Ancient Rome had more than 20 public libraries. Many of Florence’s wealthy and powerful—including several of the Medicis—hired Vespasiano to help them build their own libraries, seeking to establish their earthly status and insure their lasting legacy.

One of the delights of King’s text is his repeated turns of etymology. He discusses the origins of words like bibliography and bible, page and volume, book and library. The word for pen comes from the Latin penna or feather. Colophon, which derives from a Greek word meaning hilltop or summit, came to refer to a finishing touch or crowning stroke, before it mutated into reference to the publisher’s final addendum to a text. Vespasiano not only pioneered the use of colophons, he and his scribes also began the practice of title pages.

King dubs one of his chapters “Wondrous Treasures” and indeed, he presents many historical and intellectual treasures as he marches through Vespasiano’s world. I recommend his book to anyone eager to understand the context of Renaissance art, or of the Renaissance in general.

-

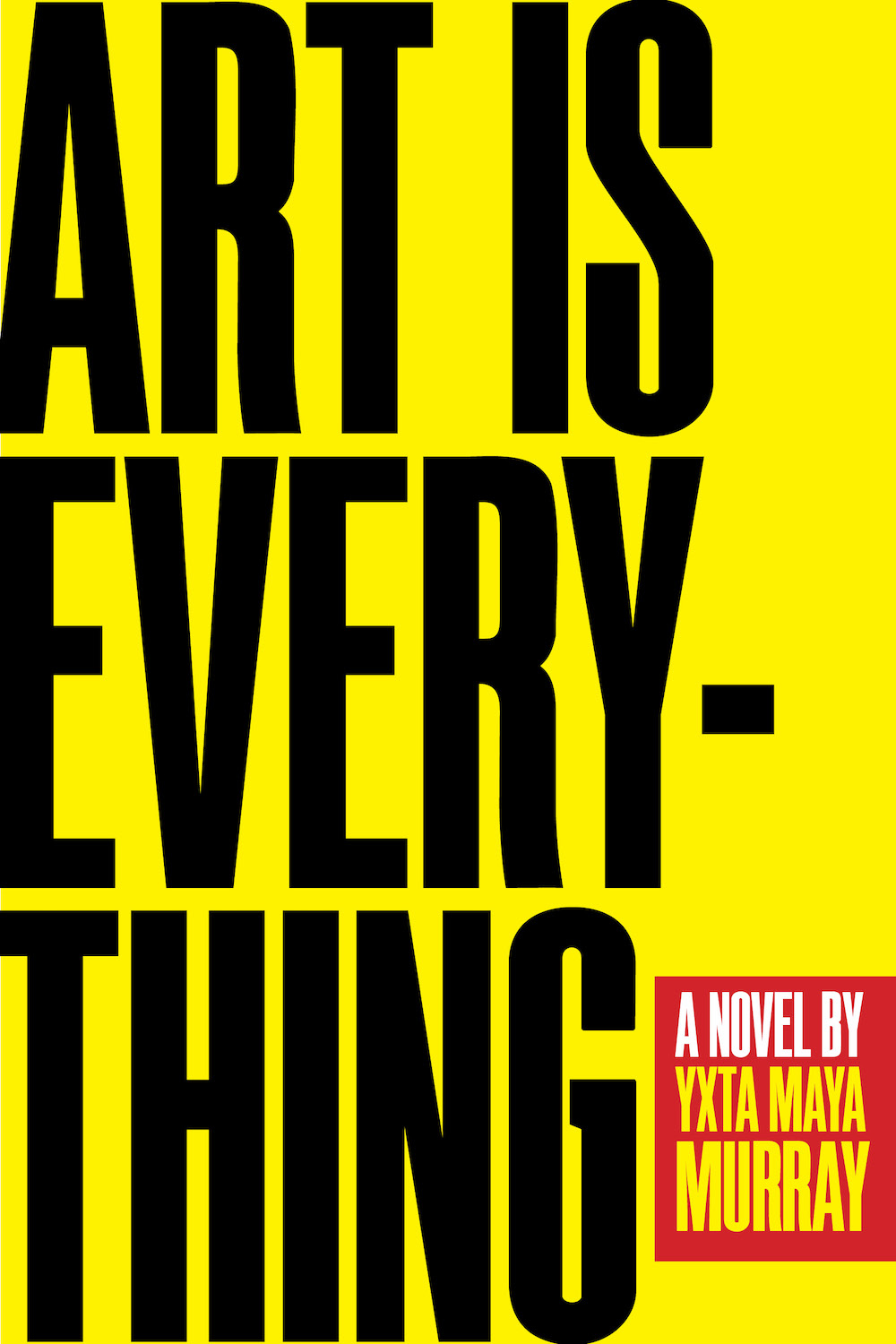

Art Is Everything By Yxta Maya Murray

DEATH OF A DREAMArt Is Everything

By Yxta Maya Murray

229 pages

TriQuarterly

Yxta Maya Murray—art writer, law professor, fiction author—draws upon the disparate threads of her writing practice to construct her new novel, Art Is Everything, a kind of Bildungsroman of the Los Angeles art world.

Written as a series of first-person confessions and guerrilla essays penned by the novel’s sole narrator, queer Chicanx performance artist Amanda Ruiz, the tale is pieced together in a series of snapshots as Ruiz’ art career rises and falls, along with her personal relationships. The novel kicks off with an article of indictment titled, “Hey MOCA, why is Laura Aguilar’s Untitled Landscape (1996) ‘Unavailable’ on Your Website?”

Interspersed with Ruiz’ essay on Aguilar’s invisibility come declarations of love and desire for her girlfriend X–ochitl Hernández, who she describes in ways that intersect with Aguilar—“large-bodied, queer, and of a complex racial background.” Exposing the kind of erasure she also encounters as a queer Chicanx artist and shares with Aguilar, she writes,“… museums either do not collect her, or they conceal her as if they are ashamed.”

The authur, photo by Andrew Brown. Ruiz audaciously places her essays as disruptive acts, hacking museum websites with unauthorized texts, subverting Wikipedia with position pieces, and leveraging social media. One guerrilla post, on the Whitney Museum website, skewers the Max Mara Whitney bag as an unattainable object and unmasks the commercialism of the art world’s high temples. Ruiz’ many compelling texts—on, for example, Sanja Ivakovi´c’s performance implicating the state surveillance apparatus of Yugoslav strongman president, Marshal Tito (Triangle, 1979); Mickalene Thomas’ Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010) and Stendhal; or David Wojnarowicz’ death portrait of Peter Hujar—are clearly informed by Murray’s art- and law-writing. Indeed, some have their origins in articles published previously, as noted in her acknowledgments. Yet they are wholly believable as Ruiz’ work, composed here in her voice.

In spite of Ruiz’ convincingness as a writer—with a punk-rock ethos—she seems miserable as an artist. Ain’t Nobody Leaving, the performance film that wins her a coveted Slamdance award, ironically documents the dissolution of her relationship with the long-suffering Xochitl, as well as a performance in the extreme—seven days of self-starvation and semi-hallucination. Yet the film feels juvenile and the dialogue utterly pedestrian: “I’m really hungry and I can’t believe that you are eating that sandwich in front of me,” and “What does love even mean?” Her other projects feel one-dimensional as well.

In an early essay on Agnes Martin and Jean Genet, Ruiz asks how artists survive a break—foreshadowing the impending attenuation of Ruiz’ art production, which withers away post-X–ochitl. In a particularly exquisite chapter titled “Private Language”—on Wittgenstein, Melville and Hawthorne, the semiotics of love, and the limitations of our subjectivity—Ruiz writes on what it feels like to be destroyed by love. The final third of the novel answers these two concerns in a variety of ways, each acknowledging the difficulty of making a life after loss and the death of one’s dreams. It is no surprise that Ruiz turns to art writing when her performance work is exhausted, for that is what she has been all along—a writer—which we readily recognize from the handiwork of Ruiz’ dexterous creator.

-

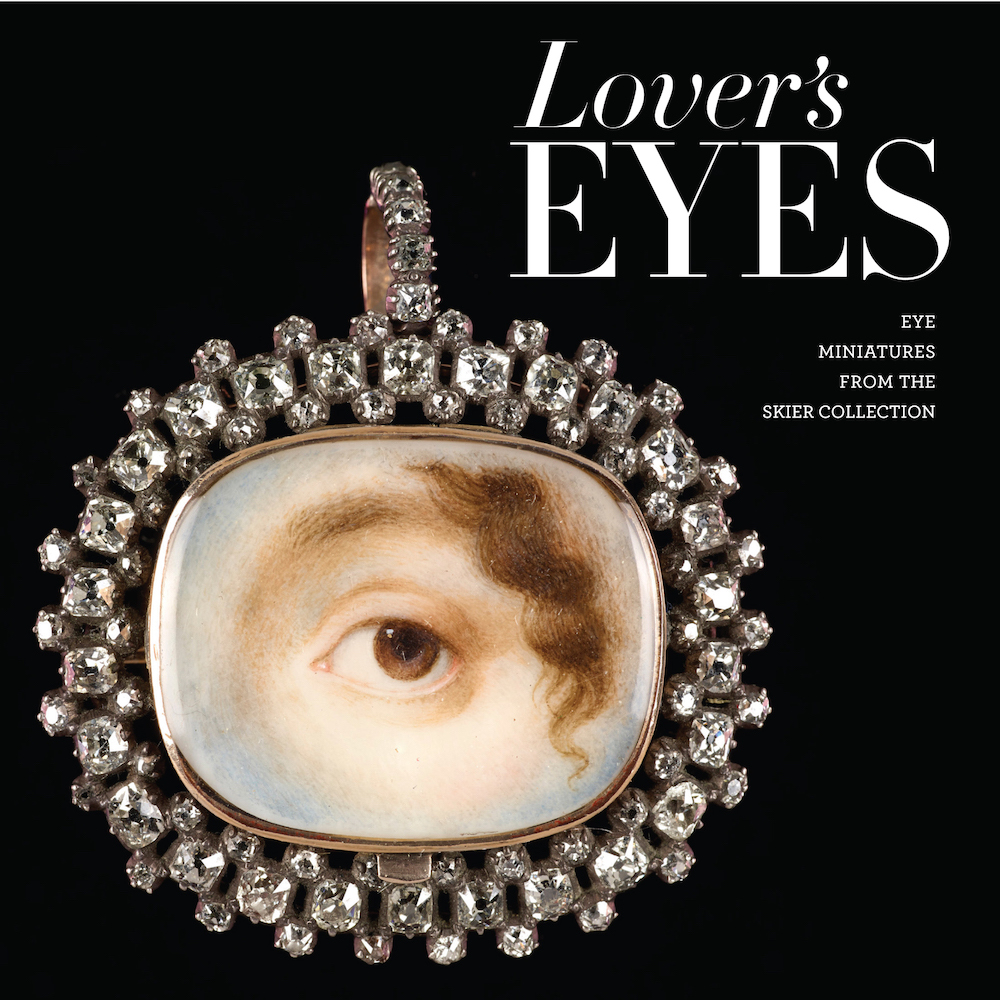

Lover’s Eyes: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection

Seeing Eye to EyeLover’s Eyes:

Eye Miniatures

from the Skier

Collection, 2021Ed. Elle Shushan;

essays by Graham C. Boettcher,

Stephen Lloyd, and Elle Shushan.

Photography by Nik Layman.280 pages

Giles Ltd.

Lover’s Eyes, a new catalog on eye miniatures, lets us peer at one of the most extensive private collections of these weird and wonderful 18th- and 19th-century works—most of which stare right back.

Eye miniatures were briefly in vogue in England at the end of the 18th century, their popularity inextricable from the story of the Prince of Wales’ love for Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert and his commission of several of the tokens. As always, the truth is a bit more complicated than the romance, and dealer Elle Shushan provides a fair overview of the trend’s history, situating the works within the traditions of portrait miniatures and sentimental jewelry. Stephen Lloyd provides further detail on court artist Richard Cosway, the best-known painter of the form. Cosway actually went unpaid for his trend-setting eye miniatures: rather than risking offense to his royal client by insisting on invoices, he leveraged the prestige of royal patronage into the rest of his business (“working for exposure” is nothing new).

Typically painted in watercolor on ivory, eye miniatures were often set in intimate pieces like bracelets, brooches, pendants or rings. The catalog also contains several boxes and a unique wallet, while the essays cover other exceptions that prove the rule—like the oddly surveilling 1840s eye miniature that was set in a mantelpiece. Essays on the symbolic languages of gems and flowers, which were often included in the miniatures’ settings or painted alongside, show much potent meaning could be contained in one tiny object and in how many ways they communicated to their viewer or recipient.

Book cover Most interesting was the essay on the afterlife of eye miniatures, a little-studied field: Graham Boettcher adds much with his survey of how later artists took inspiration from the trend. Magritte and Dali brought Surrealist takes into view; some might add the oversize eyes of the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough commissioned for the ceiling of Blenheim Palace in 1928 to that category. Boettcher also explores how contemporary artists have played ironically with the form’s conventions, from making miniatures of the eyes of famous works—a game of “spot the painting”—to creating animal eye miniatures or commemorating other fragments of the body. Fatima Ronquillo depicts people of color with and in portrait miniatures, often combining the format with the tradition of Mexican milagros, or devotional charms; her pensive works have the added effect of highlighting the racial homogeneity of the trend’s earlier subjects.

Flipping through the vast collection of eyes, I was paradoxically struck by the individuality of each one, down to the finest detail of facial features and settings. Despite—or because of—the fact that most of the eyes remain anonymous, their gazes hold endless fascination. In the context of distance and disconnection, people often look for objects that can make them feel close. We’re more likely to send a selfie than an eye these days. But Lover’s Eyes shows that time has not changed the creative variety of ways we try to look at and see one another.

-

First Person

Manifesting the Pygmalion ParableI met Mark Chamberlain in March 2003, a few days after the onset of the Iraq War. I visited a gallery in Laguna Beach to write a review of his recent work chronicling the potential horrors of that war. Mark had been mounting politically charged installations for decades. I also learned that he made his living as a fine-art photographer, and that he often brought environmental perspectives into his work.

A tall slender blue-eyed blonde with longish hair, Mark was dressed casually in a frayed work shirt and sandals. His elegant manners revealed his patrician lineage. He had a profound knowledge of history and politics and possessed a razor-like focus on saving the world.

While I admired Mark’s demeanor and insights, I was more enamored with his efforts to save Laguna Beach from rampant development. His confidence and ability to accomplish daunting tasks became the magnet drawing me to him.

We became fast friends based on our mutual interests in art, politics and popular culture. Our complementary professions—he an artist/curator, myself an art and culture writer—became the undercurrent of our relationship. As a couple, we began attending art shows and openings throughout Southern California, all the while seeking advice from each other about our own work.

I moved into Mark’s Laguna Beach home in 2010 and spent several years there with him. We shared meals, watched historical programs on TV, and discussed political, social and personal events. Mark told me stories about growing up in Dubuque, Iowa, exploring the area’s topography and riding boats on the Mississippi River. I shared my memories of a Jewish childhood in the suburbs of Manhattan. We went on the road and spent a week touring his hometown of Dubuque, staying in his houseboat on the shores of the Mississippi.

Liz Goldner & Mark Chamberlain, Main Beach, Laguna Demonstration We edited each other’s writings and began collaborating on curatorial and journalistic projects. These included a book about his Laguna Canyon Project, an art concept that helped save Laguna Beach from suburban development in the 1980s. As we collaborated, we often struggled with—though eventually resolved—our differing opinions about words, phrases, descriptions and intent.

An unfortunate aspect of Mark’s confidence was his belief in his indestructibility. This attitude often drove him to stretch his body beyond its capacity, spending six weeks every summer laboring on his Mississippi houseboat. He also smoked, stubbornly insisting that the habit would not damage his body.

This lifestyle eventually caught up with him. He returned home from a grueling Mississippi trip in August 2016 with a heart infection. Soon after, he developed atrial fibrillation. While receiving numerous treatments for this condition, he continued to work intensely, and smoke.

In December 2017, Mark felt pain in his lungs and had difficulty breathing. He was told that he had terminal lung cancer. He accepted this diagnosis with quiet resignation.

For the next several months, Mark’s breathing was aided by oxygen 24/7. In March 2018, after receiving immunotherapy, his cancerous tumor broke up, filling his lungs, making breathing more difficult. He went back to the hospital where he spent his final six weeks. The book we completed earlier that year was finally published, which brightened his outlook.

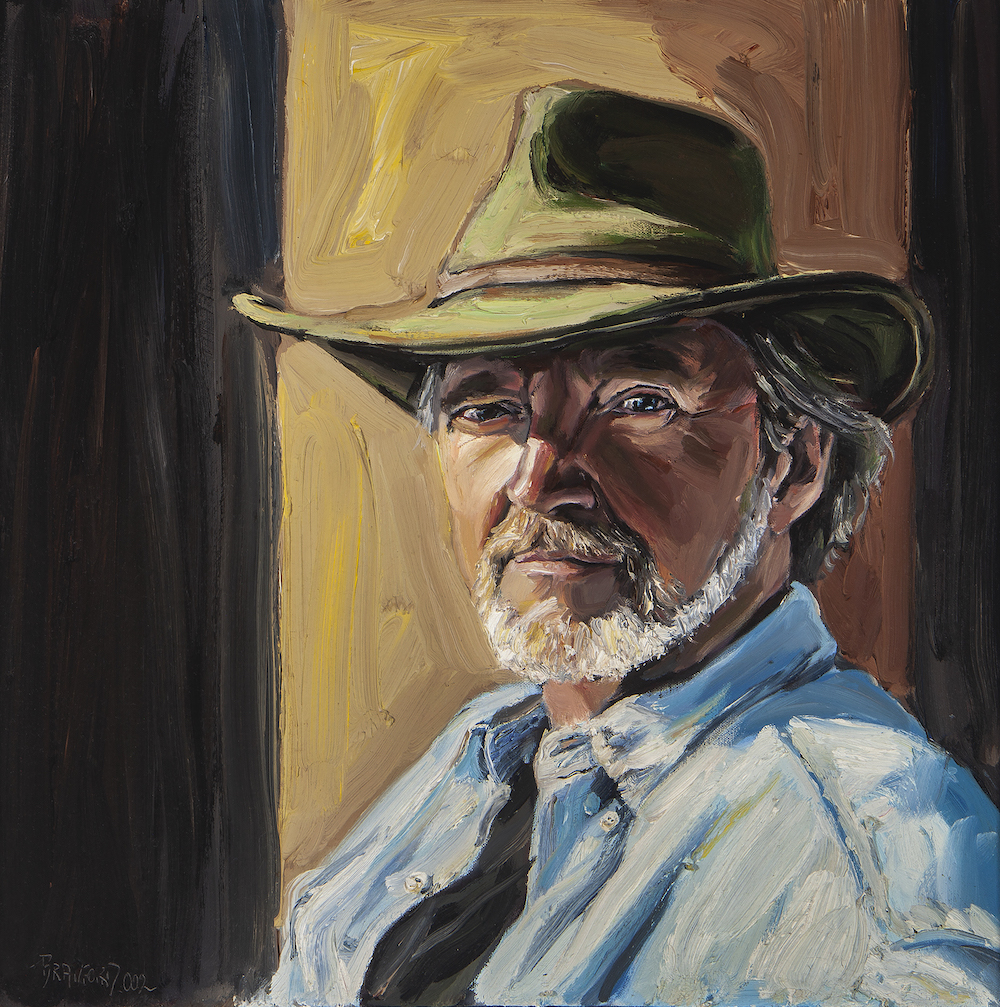

Mark Chamberlain at Soka University exhibition In late April, I told Mark how much I appreciated him and how I had evolved creatively during our relationship. He responded by talking about the Pygmalion parable, in which a sculptor brings a statue he has created to life. Through his influence and encouragement, I had grown in my life, relationships and work.

Mark passed away on April 23, 2018. An artist friend later told me, “It is a gift when art can create connections with human emotions and interactions.” In fact our mutual love for art and humanity, our shared passions and the larger world had become the glue in our relationship.

Mark’s mission to save his community through his art and empathy for others were so profound that three years after his passing I still feel his presence in the expansive Laguna Canyon, which he fought so valiantly to save. His magnanimous Pygmalion-like nature continues to nurture my heart, mind and soul.

-

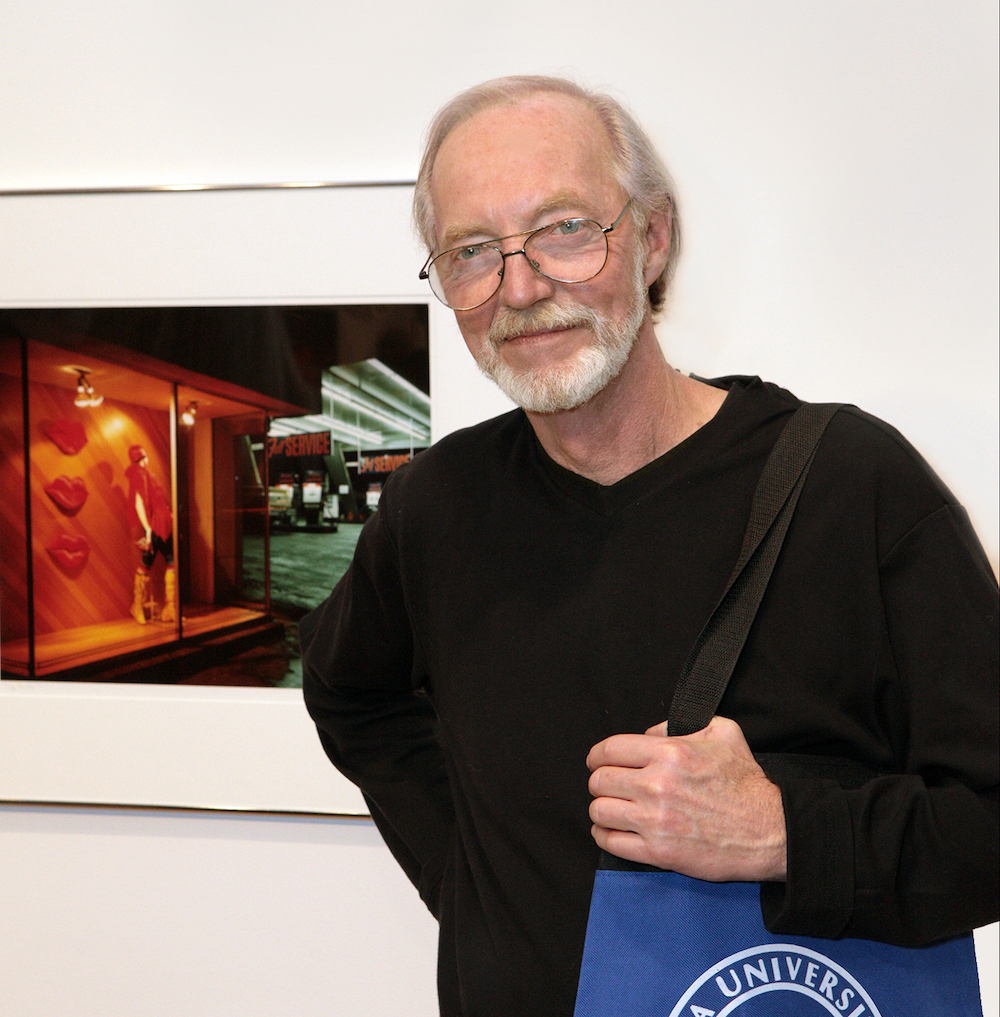

NoLab By Richard Roth

WHODUNIT?NoLab

By Richard Roth

232 pages

Owl Canyon Press

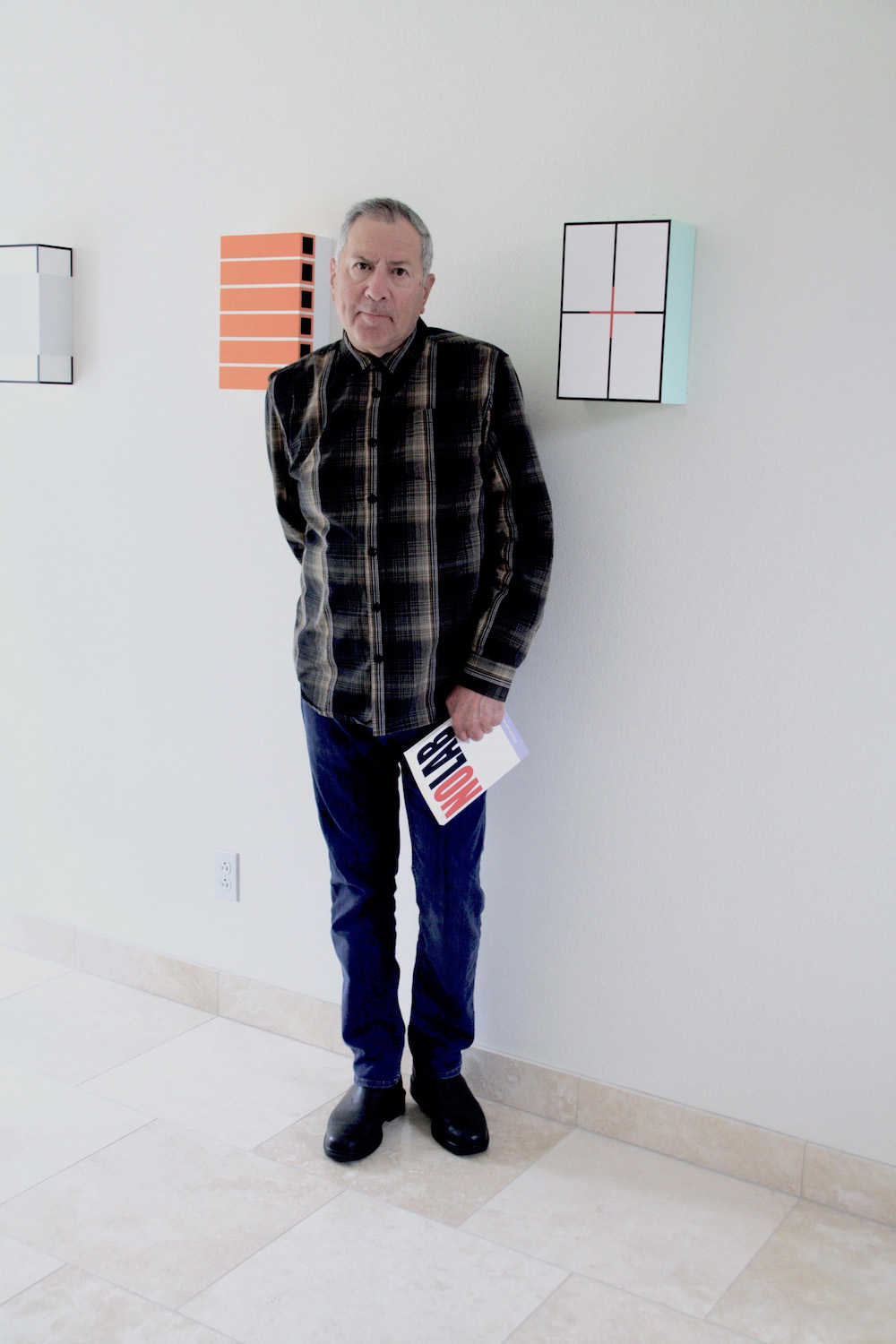

Being a voracious reader of contemporary fiction with a particular interest in mystery novels, thrillers and mysteries about artists and art thefts, I was excited to happen upon Richard Roth’s novel NoLab (2019) earlier this year. NoLab recounts the story of two artists hired to search for the collective, NoLab, that has mysteriously disappeared. What I liked most about the book was how Roth got it right and was able to construct a thrilling read that presented the contemporary art world in a thoughtful and believable way.

I contacted Roth after finishing NoLab, to tell him how much I liked his book and how I appreciated his insights.

JODY ZELLEN: Can you talk a little about the inspiration for the different artworks described in the book? Early in his career, the protagonist Ray Lawson, created pills that were works of art that altered perceptions but now he makes more traditional paintings. NoLab’s project took its point of departure from Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky project while Ray’s cohort, Victor Florian’s works received their due after his death.

Richard Roth: One of the thrills of writing NoLab was the opportunity to invent the various works of art made by my characters. As one who has spent his life involved with all things visual, alone in a silent wordless studio, writing fiction was a shocking and intoxicating adventure, a medium in which I could create dangerous and massive works of art, impossible to actually realize in this world. And, as a reductive abstract painter, I stand in awe of writing as the ultimate reductive medium. With those 26 little letters of the alphabet, one can build skyscrapers, as well as the people who live in them!

Ray Lawson’s early work, as well as NoLab’s, are somewhere between conceptual and performance art. How far can artists take such things as death and mind-altering drugs and still be considered art? Do you feel freer writing a work of fiction than thinking about making the works?

It seems to me that we are living in a time in which almost anything can be considered art; whether something is or is not art might just finally depend on the absolute conviction of the maker. I’m certainly not advocating an art that is immoral or infringes on the rights of others, but as a writer, presenting extreme practices invites readers to consider ethical issues, and it does so, hopefully, with some energy and flair.

How does being an artist and writer yourself come into play in the book? Did it give you special insight into your character?

I have been a painter since my undergraduate days at Cooper Union, then much later, beginning in 1996, my practice became more conceptual—creating collections of contemporary material culture. I returned to painting in 2006 with a renewed and revitalized interest, fueled by Conceptualism and informed by Postmodern attitudes. The trajectory of my studio practice resembles the career of Ray Lawson, my protagonist, but with a hell of a lot less drama. So, yes, I can’t imagine how I could have created the characters in NoLab without a life spent painting and teaching.

Are any of the characters in NoLab based on specific artists? Hybrids of multiple artists?

Hybrids of multiple artists! During my years teaching painting to graduate students, a number of them have incorporated aspects of performance, conceptual art and relational aesthetics into their work. I must admit that I enjoyed and encouraged some unruly and disruptive student practices. Occasionally, an especially iconoclastic student would come all too close to performing an unethical or illegal action. On these occasions, I would wonder what would happen if a student went too far, I mean really too far. This recurring thought was the inspiration for NoLab. The novel was my chance to create a fictional artist’s collaborative hellbent on carrying out a dangerous project, and it was my chance to talk about an art world that is at once both nonsensical and magical, and it was my chance to have some fun along the way.

Do you have plans to write another art novel?

I began writing a second novel shortly after NoLab’s publication. It’s not focused on the art world, but close enough—the protagonist is an architect. Though the novel (working title: Cooper) touches on issues concerning architecture, after four years of Trump and a year of COVID, Cooper is morphing into the sad and angry story of a man besieged.

-

Suitcase Joe and the State of Homeless Photography

Sidewalk ChampionsSidewalk Champions

By Suitcase Joe

Burn Barrel Press

In the wake of the unprecedented court decree issued in April by a federal judge ordering the city of Los Angeles to provide shelter for the 4,600 souls currently living in downtown skid row by this October, the work of photographer Suitcase Joe could not be more timely. His recently released book, Sidewalk Champions (Burn Barrel Press), will consequently provide a valuable historical account of what this urban dystopia looked and felt like at the height of its sprawling horror.

Photographic documentation of the disenfranchised dates way back to the Gilded Age in 19th-century America when the manifestations of extreme wealth inequity were eerily parallel to the here and now. The first devotee to social documentary photography was the fascinating figure Jacob Riis who pioneered the use of flash photography, allowing him to light up dark tenements and alleyways occupied by New York City residents (especially children) living on the ragged margins of urban life.

Riis’ tireless efforts exposed inhumane living conditions to the middle and upper classes for the first time, igniting an era of social reform that came into full fruition during the Great Depression with the creation of the influential FHA.

Yet today’s images of the homeless rarely move or surprise us anymore. Due to advances in technology that make taking and sharing pictures more expedient, portrayals of their plight oversaturate the media landscape, inuring us to the urgency of the issue—the opposite effect pioneers like Riis intended. Add to that the public’s growing (and often unfair) accusations of exploitation by those who photograph homeless populations, trying to shed light on the injustices of the human condition has become challenging and treacherous for even the most well-intentioned photographer, beyond the already considerable physical risk of working in dangerous neighborhoods.

Left to Right: A Father’s Love; Old Man Mel; Man Down, Name Unknown Suitcase Joe’s skid row series warrants serious consideration, due in part to its high degree of humanity that succeeds in evoking our empathy. Unlike most contemporary photography depicting homelessness, his subjects are not remotely rendered as generic representations of a sociological condition; rather, they are portrayed as emotionally animated human beings with their own unique manifestations of struggle and survival. The images are often tender and poignantly observed; he does not mistake physical proximity for genuine intimacy. Yet he spares us an excess of cliché graphic close-ups—like heroin needles being injected into filthy arms—which only serve to reinforce stereotypes and cause us to look away instead of draw us in.

Bath in a Tent Stylistically, he forgoes formal rigor and more deliberately conceived lighting for freewheeling lyrical spontaneity that enlivens the photos with refreshing gusts of warmth, surprise and even humor.

As a whole, the impressive breadth and depth of the work demonstrates a long-term commitment to the subjects who—based on their relaxed and even light-hearted expressions in many of the images—clearly know and trust Suitcase Joe. In both his photos and poignant introductory text, it’s clear he’s forged a special relationship with the Skid Row community that has enabled him to perceive and render the complexities of homeless life with greater detail, honesty and compassion.

A Skid Row Celebration “. . . If you dive beneath the surface you find some of the most kind and generous people stemming form all walks of life . . .”

“Skid Row is both beautiful and horrific and cannot be weighed fairly in one particular way. It is as complex as an civilization with its own wars and triumphs being fought and won everyday. Each block with its own inner workings and social hierarchies that contribute to the greater heartbeat of the community at large.”

… Skid Rowe is home to society’s castaways and have-nots, and necessity has born them into engineers, hunter gatherers, and a school of deep thinkers with poignant and poetic tongues. For all the books you can read about human nature and our instinctive will to survive – there is no better university than the streets of Skid Row.”

– Suitcase Joe

-

In The Spotlight: Paul R. Williams

Two books on the ArchitectMaster Architects of

Southern California 1920–1940by Marc Appleton, Stephen Gee

and Bret Parsons208 pages

Angel City Press

Regarding Paul R. Williams:

A Photographer’s Viewby Janna Ireland

224 pages

Angel City Press

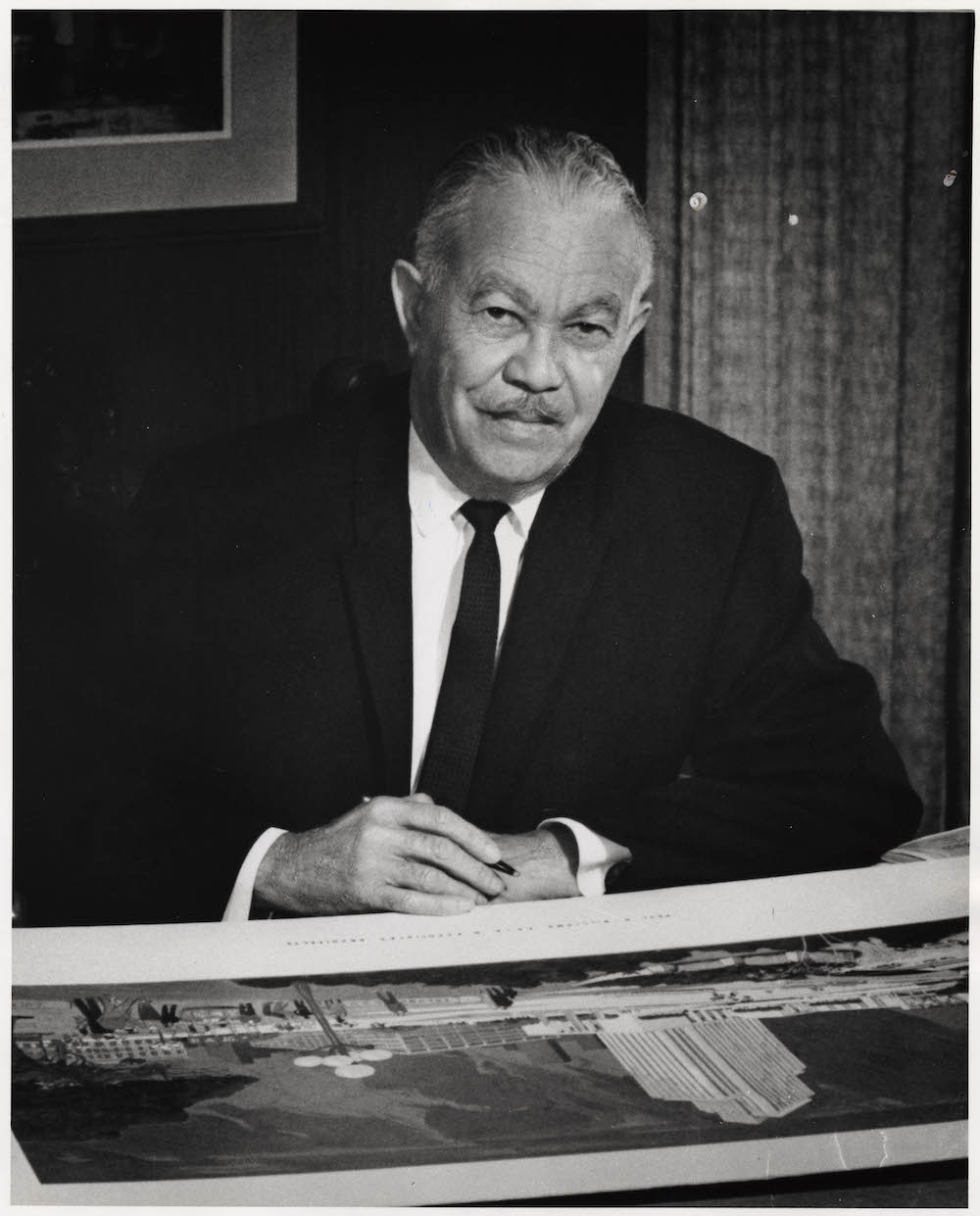

When Paul Revere Williams died in 1980 at the age of 85, he left behind one of the most remarkable legacies in Los Angeles architecture. He not only designed homes so elegant and livable that he was avidly sought after by such celebrities as Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Barbara Stanwyck and Lon Chaney, he also designed institutional and commercial buildings that are with us still such as the Beverly Hills Hotel and the New Hope Baptist Church. When still in his 20s, he was appointed to the city’s first planning commission. In 1923 he was elected to the American Institute of Architects, the first African American admitted.

Two books about the architect have come out recently, both from our own Angel City Press. One is part of the Master Architects of Southern California 1920–1940 series, written by Marc Appleton, Stephen Gee and Bret Parsons and utilizing pages from Architectural Digest magazine when it was based in Los Angeles. The other book is Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, by Janna Ireland, who spent several years photographing the exteriors and interiors of Williams’ extant buildings. If you live in the greater Los Angeles area, you have passed by or walked through one of his buildings—he designed some 3,000 of them, including some in other cities. Unfortunately, a number have been demolished.

Paul R. Williams. From Master Architects of Southern California 1920-1940: Paul R. Williams. The Master Architects volume is a terrific reference, opening with a well-researched and detailed biography of Williams and his career. Then 30 residential and commercial projects are featured, pages from Architectural Digest supplemented by new editorial material. The vintage pages are on a light tan background, clearly setting them apart from the new material. In most cases specific addresses are left out—that would have be useful for architectural buffs like me, who like to go look at actual buildings.

Both books point out that Williams learned to be adept at many styles—including Tudor, Georgian, Mid-Century—and in both residential and institutional designs. The fact is he had to be, to get enough clients to support his family and his business, and he had ample talent to do so. After working for several well-established architects, he set up his own practice in 1922 and worked hard and long enough to see it flourish. Due to restrictive covenants, he couldn’t live in upscale Hancock Park where he designed many a mansion, as seen in these books. After such covenants were declared unconstitutional, he did build a pretty impressive home in Lafayette Square, in the spare, sleek International style.

Hillside Memorial Park Mausoleum and Al Jolson Shrine, 2019 From Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, page 147. Ireland was introduced to Williams by Barbara Bestor, one of LA’s leading architects, who suggested this project to her and helped her make contact with several homeowners. As Ireland, who is African American, delved into Williams’ life and work, she saw parallels with her own career, and admired how he faced down the pervasive racial prejudice of his times. For example, he learned to draw upside down, so that he could draw for clients without them having to sit next to him. “When I began my project,” she writes, “this and other stories about Williams’ knack for turning indignities into triumphs intrigued me.”

The photographer uses an artist’s eye in capturing these black-and-white photographs. There are wonderful details of cornices and sweeping staircases, as well as overall shots of the buildings in their settings. The pictures are not arranged chronologically or by style, and one building may pop up in different parts of the book. As a former picture editor, I would have laid this book out differently, but I think there is some visual rhythm to the layout as it is. A more nagging issue is that the mid-tones of the pictures are a bit muddied, which might have been adjusted during proofing and/or using a different paper stock.

Seaview Community, Rancho Palos Verdes, 2018 From Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, page 134. Both books are very timely. It’s certainly time our knowledge of LA’s architectural history expanded beyond the Case Study houses and what Bestor calls “the modernist orthodoxy.” These books contribute to our understanding and appreciation of a singular talent—a man who helped define the look of our built environment.

-

POST YORK

Story and Art by James RombergerPost York

Story and Art by James Romberger

with additional material by Crosby Romberger

112 pages

Dark Horse Comics/Berger Books

“They somehow set fire to what was left of the East Side.”

—POST YORK, p.86.

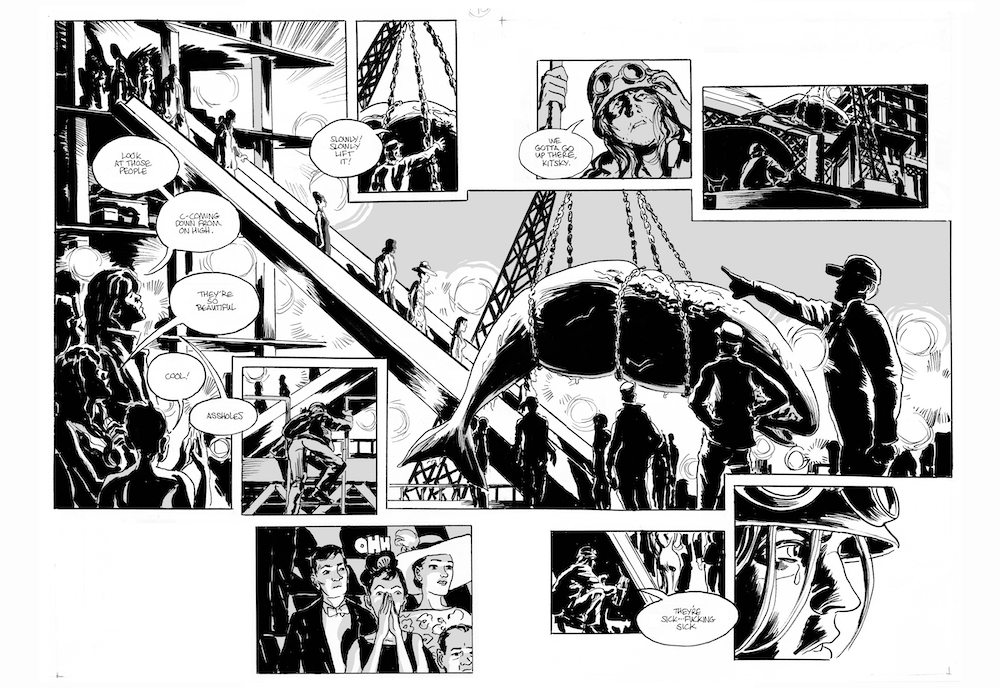

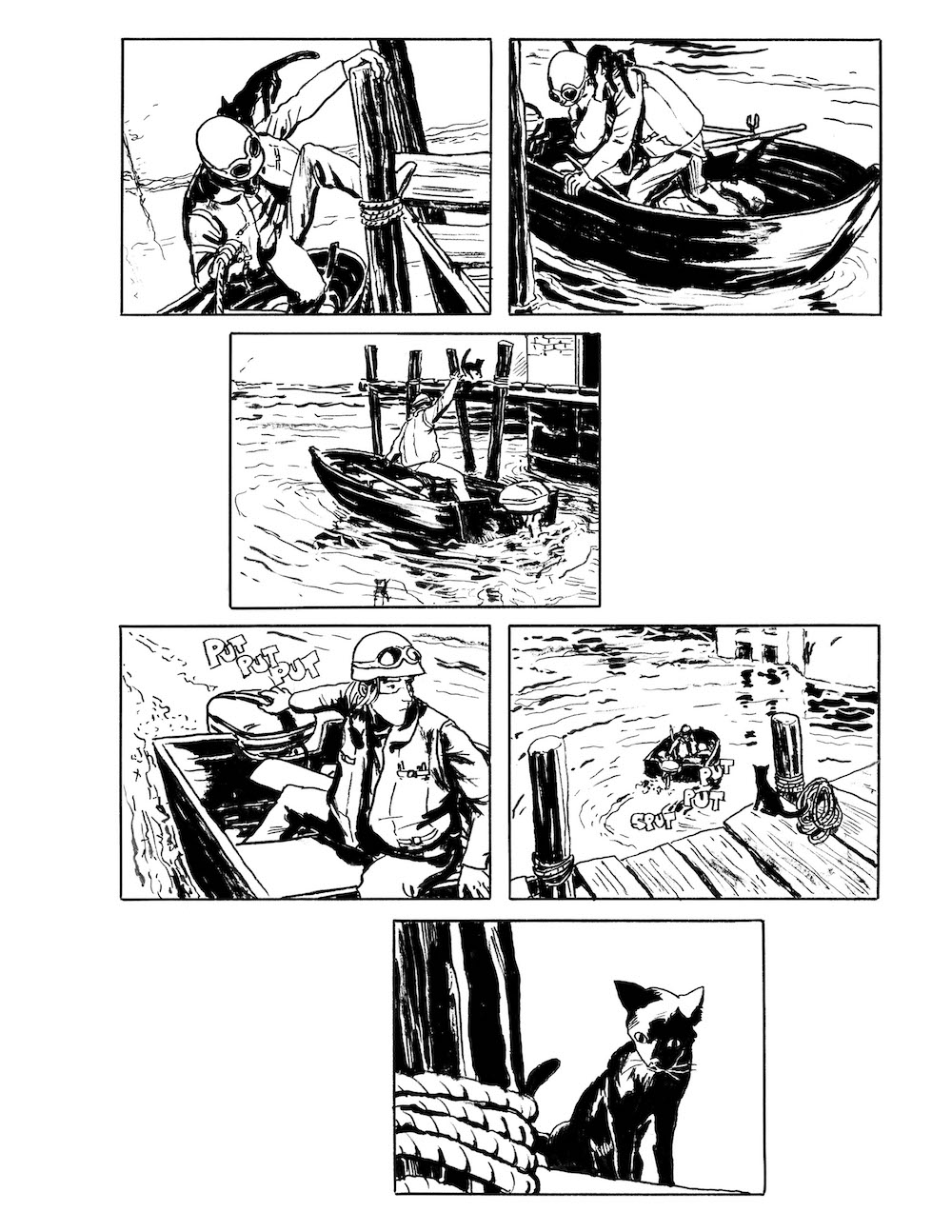

The city had been ceded to climate change. It was drowned, abandoned, gone wild, given over to the feral young: a hostile, black-and-white environment, prone to violence but still susceptible to love. It was POST YORK.

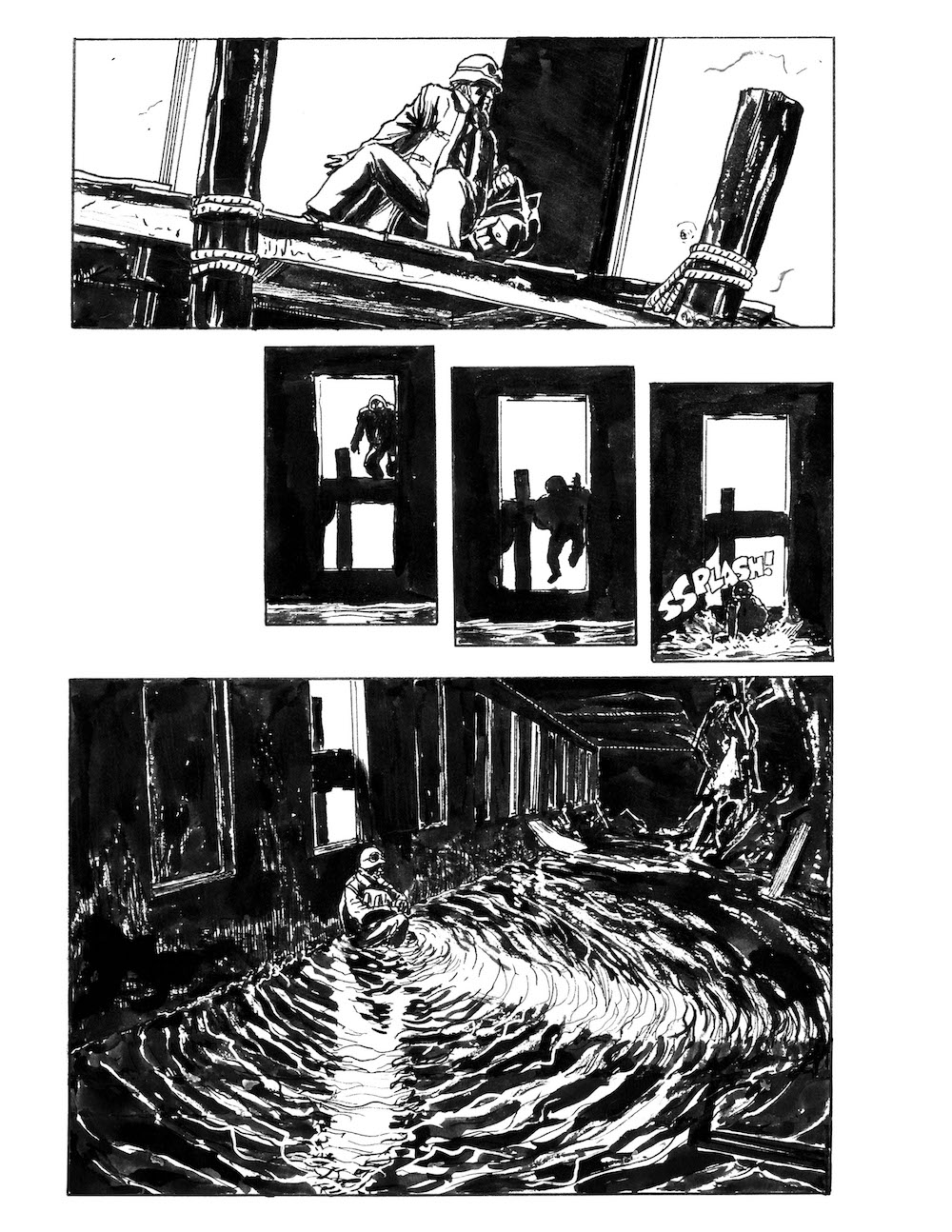

POST YORK is a graphic novel of striking immediacy, a near-future dystopia with an in-your-face punch. Lacking all the context that might characterize a contemporary climate disaster newscast, the novel begins quite simply, as an adventure in daily living in the flooded ruins of a post-apocalyptic New York City. Crosby, the novel’s protagonist, searches the submerged city in a dinky motorboat, rustling food for his cat, Kitski. He finds a cache in a deserted movie theater inhabited by a pretty young squatter named Ivy. She confronts Crosby. They fight. An uneasy truce ensues, sealed by an act of accidental barter. Ivy smiles as she admires her new helmet. Crosby heads home to the hungry Kitski.

Page 5 from POST YORK However, several subsequent panels of rain pouring down on empty exteriors suggest a more malign reality. The city’s only denizen appears a lonely and bedraggled pigeon, looking very like Noah’s land-seeking dove, perched on a sleek light stanchion. And there is no respite from the deluge.

Rather, this low-key narrative becomes the template for a thrice-recapitulated sequence of events, which begins each time with Crosby’s decision to set out on his cat food quest. With each subsequent retelling, this basic story is radically altered by chance and circumstance. The stakes of play are ratcheted up: Crosby’s tussle with Ivy ends in death (the most bleak and “existential” of the three scenarios); whales and sharks patrol the turbid waters; bloody vengeance is exacted for an accident; the rich and morally corrupt cannibalize a living whale as the East Side burns (ecological and social lessons are drawn); transgressive desire becomes a weapon; art passes away; two might-be lovers are [re]united at a party marking the End of Civilization. A final ray of light is teased: “I’m Crosby. I think we can change this story.” (p.101)

Page 14 from POST YORK In terms of style and thematic structure, the book presents some interesting contrasts. Romberger’s visual style is a brutal, slashing black-and-white, stripped down and intensely powerful, but also able to catch fine physical nuances: Crosby’s incredulity or his determination, Ivy’s pouting beauty. The visual structure is also cinematic and the transitions frame to frame are dynamic and fluid. Much of the narration proceeds without dialog and we are left to imagine a rich extra-vocal soundscape. And the novel reflects on its own status as art with reference both to cinema and Renaissance fresco (pp. 46–47; 69; 84–87: a beautifully drawn-out argument). The politics are radical, eventually holding up a mirror to an elite culture in a state of utter moral and existential collapse. But there is room for love, and the relationship between Crosby and Ivy may be touched by Grace. At least, it’s a possibility.

NOTE: In addition to the novel proper, there is also (among other additional material from James and Crosby) an illustrated history of the project, and a set of annotated endnotes that will help the interested reader orient herself with respect to the scientific and public policy material consulted by the author.

-

Alice Neel at The Met

“People Come First” at the Metropolitan Museum of ArtAfter living through the angst-laden whirlwind that was 2020, I can’t imagine a better show to see than “Alice Neel: People Come First” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Neel’s dual focus on ordinary, often invisible people and social justice issues resonates powerfully and offers a kind of corrective symmetry to Trump, COVID-19, and the violence against people of color epitomized by George Floyd’s murder. The world has caught up with Neel, not just stylistically, but also politically.

A true bohemian, Neel (1900–1984) operated outside the art establishment for most of her career. She left Greenwich Village and the New York art scene for Spanish Harlem in 1938. She never divorced the husband she married in 1925, taking lovers and having sons by two of them. A nonconformist herself, she was naturally drawn to others, painting pictures of artists, gay couples, underground performers and political activists.

Neel’s nonconformity extended to her erotic watercolors and her approach to the nude. Her many portraits of heavily pregnant women showcase this fundamental aspect of life that had previously been taboo. In 1972, she turned her gaze on poet and art critic John Perreault, depicting him in full-frontal naked glory. Continuing her explorations, she painted Cindy Nemser and Chuck (1975) seated somewhat tentatively in the all together on a formal Empire sofa, and, with extreme lack of vanity, her own 80-year-old self, naked as a jaybird.

Self‑Portrait, 1980, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., ©The Estate of Alice Neel. Like a caricaturist she exaggerated people’s features; her goal was not humor, but highlighting her subject’s essence. This approach extended beyond her sitters’ visages to include other body parts, clothing and furniture, overemphasizing, for effect, their individual characteristics.

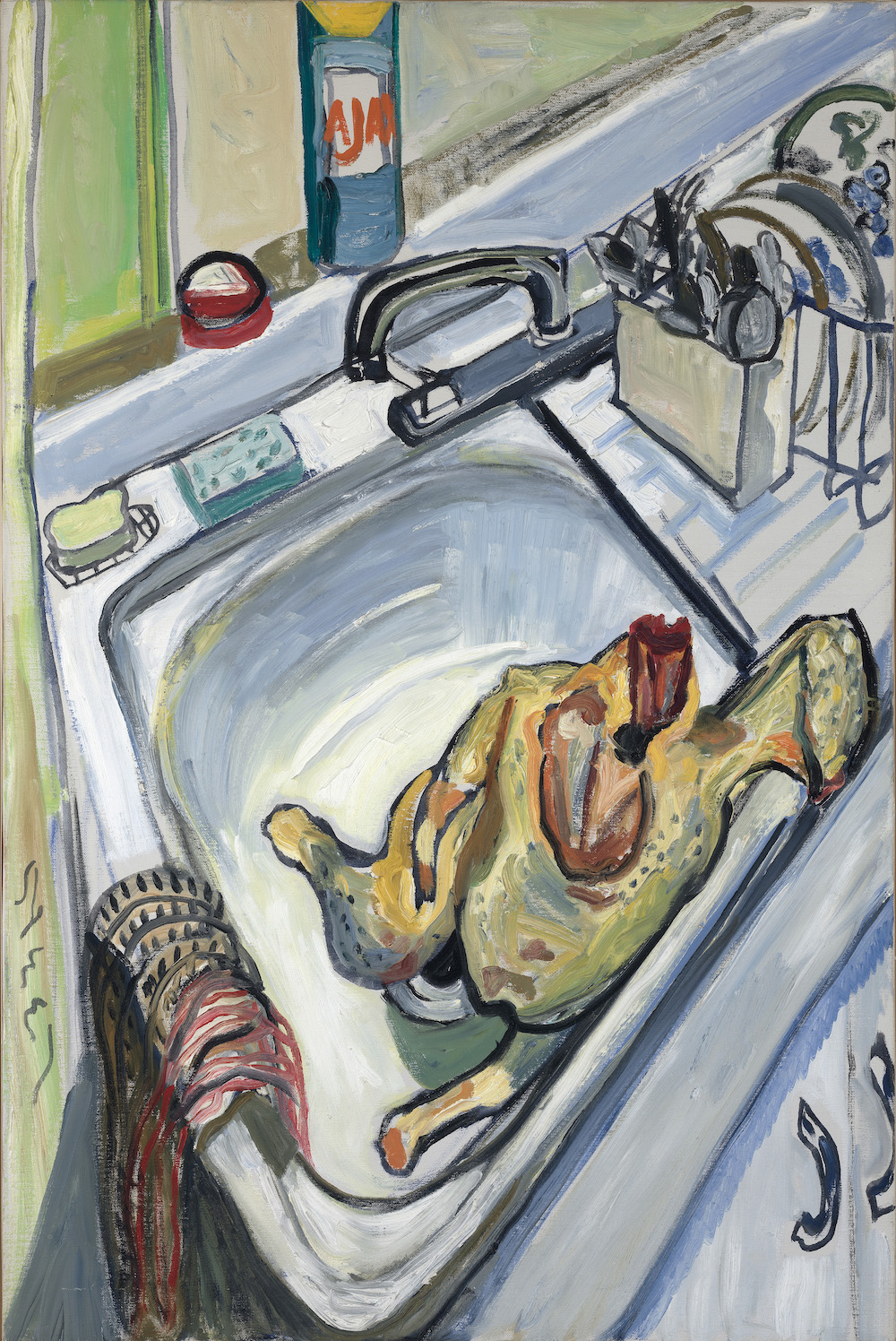

Neel invested nearly the same intensity into objects and pieces of furniture. Thanksgiving (1965), a portrait of her kitchen sink, boasts a lively assortment of soap, sponge, rags and Ajax joined by a turkey carcass slumped in a corner. In Cut Glass with Fruit (1952), a fluted dish and compote come alive with a crazy quilt of crosshatches, slashes and shapes that somehow coalesce to produce the exact quality of those kinds of dishes. Neel couldn’t afford a studio and painting in her apartment often included pieces of furniture like the blue-and-white striped armchair that appears in her nude self-portrait, Black Draftee (James Hunter) (1965) Benny and Mary Ellen Andrews (1972) and other works.

Thanksgiving, 1965, The Brand Family Collection © The Estate of Alice Neel Neel uses pattern to great effect, inserting a striped shirt, an Indian handblocked bedspread, or a plaid bathrobe. The motifs and colors are often quite bold, but she doesn’t overdo it, using one, or perhaps two, and keeps it fresh and unpredictable by sometimes not using any pattern at all.

For Neel, who felt very strongly that man was the measure of all things, abstract art was anathema. Yet again and again in her paintings, the formal elements—color, composition and gesture—have a stand-alone weight and importance that transcends the representational aspects.

Trading off the heavy black line that surrounds the subjects in her earlier works for electric blue was an inspired adaptation that breathes vitality into the work. Neel also began to leave sections of the paintings unfinished. This helped direct attention to the more detailed sections, namely the face and eyes, but it also imbued the paintings with modernity. In the case of Black Draftee (James Hunter), she uses it serendipitously for dramatic effect. The recently drafted Hunter never returned for his subsequent sittings. It was the height of the Vietnam War and Neel embraced the unfinished aspect of the painting as a powerful metaphor for Hunter’s presumed unfinished life.

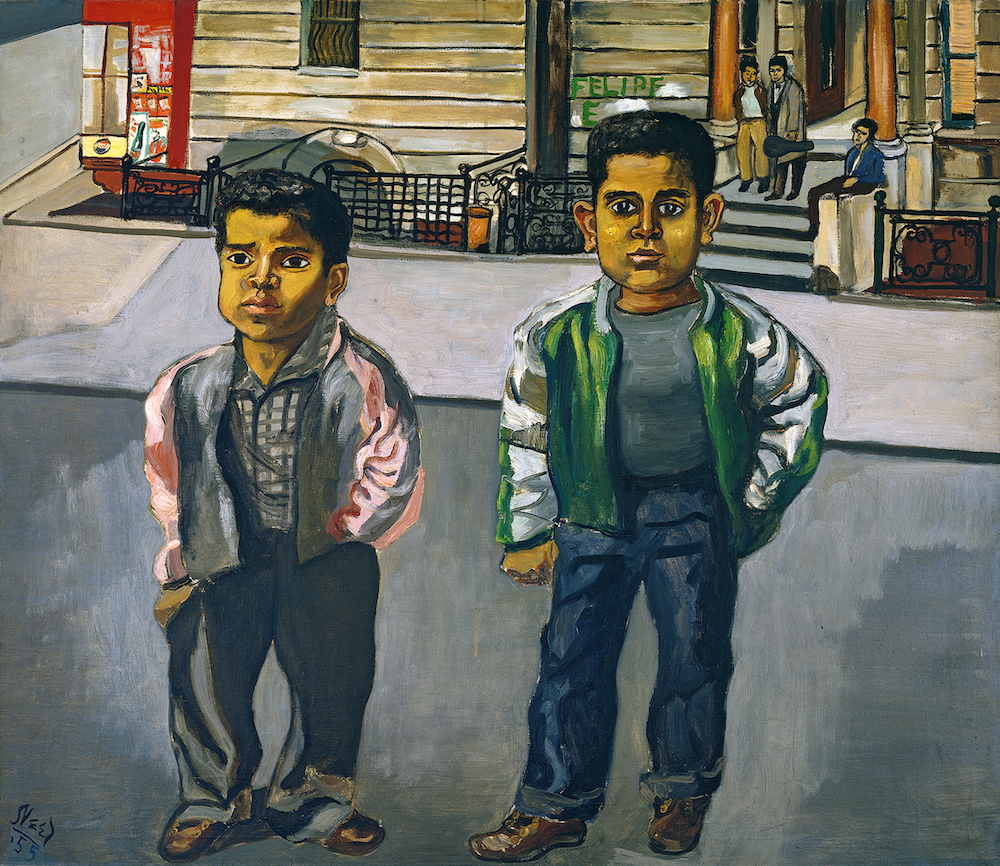

The Spanish Family, 1943, © The Estate of Alice Neel Neel treated her youngest sitters with the same gravitas she did their elders, understanding that children are individuals, and childhood is not always the easy, carefree existence it’s purported to be. Solemn and soulful, Two Girls Spanish Harlem (1959) and The Black Boys (1967) painted before and just after the Civil Rights Act, present these small humans with great empathy. Their expressions suggest they already know the tough road that faces them ahead.

Richard (1963) and Hartley (1966) are powerful psychological studies of the artist’s sons. Direct and confrontational, the boys stare out at the viewer. Richard is warily buttoned up, Hartley more relaxed. Neel uses a similar palette in both—mauve, burnt sienna and ochre to describe the merest suggestion of a background. The brushwork used to convey the clothes is extraordinary, particularly the dynamic folds of Hartley’s rumpled khakis. His arms, stretched over his head, are long and lean with the slight bulge of his left bicep capturing the exact quality of a young man’s tender musculature.

Hartley, 1966, (detail) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gift of Arthur M. Bullowa, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art ©The Estate of Alice Neel Moving through the galleries, you see Neel’s evolution as she worked through the dour portraits of the ’40s, distinguished by that heavy black line and somber colors. She had a lot of personal burdens—a dead child, a lost child, a couple of abusive relationships, poverty and lack of professional recognition coupled with fierce ambition—and yet, we see this remarkable transformation occurring from obdurate gloom to a kind of joy. It’s not that she felt the weight of things any less—she remained politically engaged all her life—but it’s as if she attained a kind of acceptance or, at least, shifted her focus from the conditions surrounding the subjects she painted to the people themselves, finding bliss in representing them just as they were.

And how they were! One’s heart warms to this messy jumble of humanity that at once seems so immediate and also from a simpler, more authentic time before the avaricious 1980s, the AIDS epidemic, 9/11, Citizens United and social media. While working in opposition to the many injustices and alienating forces in America, Neel captures what the world, and New York in particular, looked like. Viewing it through post-2020 lenses and following months of isolation, Neel’s world—where people come first—seems ineffably appealing.