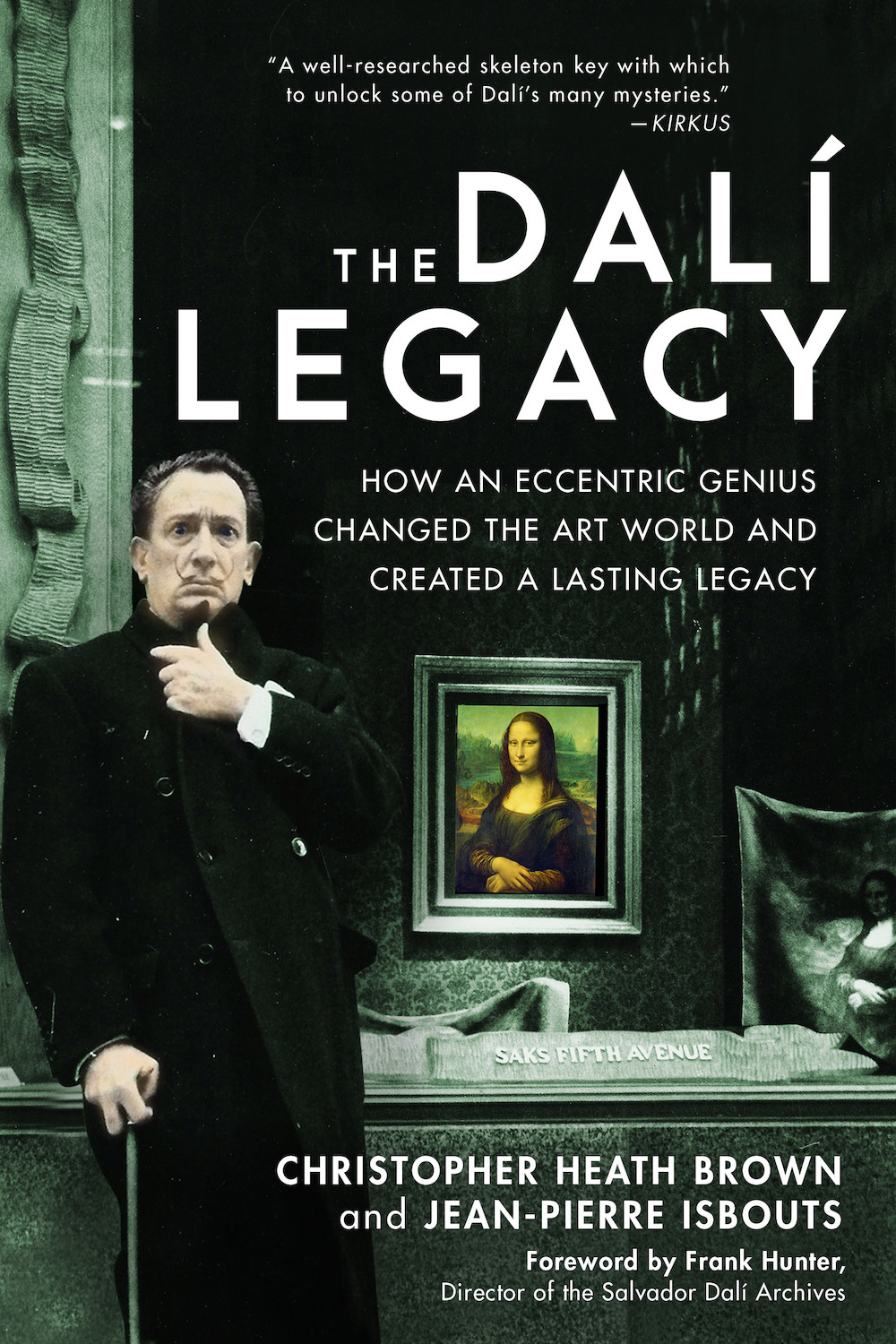

Salvador Dali has always had a troubled relationship with the Art World. His work embraced figurative representation during a century where deconstruction and reinvention were the mode du jour. His theatrics often upstaged his considerable talent. The amount of energy he expended playing the role of eccentric artist often distracted critics from the solid theories and concepts that underlie his work. By the final years, when he was signing blank paper to raise cash, “serious” collectors eschewed his work. Part of the reason for this was his popularity. No matter how hard the gatekeepers tried to keep him out of the canon, his popularity with the general public has never waned. There are museums in Florida and Spain dedicated solely to his work, and they rarely suffer a shortage of visitors. A new book, The Dali Legacy, untangles the chaos of obfuscation and myth from the solid underpinnings of concept and technique. This might be the first book to focus on Dali the painter and theorist.

Book cover.

The book is chronological. It starts out with a good overview of the world that shaped him. One bit of great detective work involves figuring out which paintings he might have seen at an early age, based on where he grew up. Using the museums in the area as a guide, it is possible to determine what he might have been exposed to. The authors also do a good job of explaining what a printed painting would have looked like at the time (black-and-white approximations), and how startling it would have been to see a crisp version in full color. As we gain a clearer understanding of the art that shaped Dali’s outlook, we are afforded a better understanding of why he approached certain techniques and subjects as he did. When he heads off to art school, he is a bit furious that nobody is teaching old master techniques.

Salvador Dalí, Corpus Hypercubus, c. 1954

© 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights

Society. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image

source: Art Resource, NY

As Dali strikes out on his own as an artist, we get a sense of how his approach was viewed by his peers. He was embraced by the surrealists before he was expelled for his politics, which were mostly the politics of convenience. Though he voiced a fascination with Hitler as a charismatic figure, he never expressed Nazi sympathies. Most of the pro-Franco stuff was the result of wanting to keep his studio in Spain. Given that the Met had to offer a disclaimer on the Stein art collection because of Nazi collaboration, he was perhaps less alone in these gray areas than was previously assumed.

Salvador Dalí, Study for The Skull of Zurbarán, 1955

© 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights

Society. Photo credit: Chris Brown Collection

By the time Dali was 30 he had already produced his most known art work, The Persistence of Memory (1931) using his Paranoid-Critical Method. Most of what we think of as the classic Dali nightmare work was produced during this period. This is usually where Dali biographies begin to lose their focus. By now he was a famous eccentric, with loads of anecdotes and accompanying salacious gossip. The authors treat his 1939 World’s Fair pavilion as a work of art, but otherwise tighten the focus for the rest of the book to his evolution as a painter. This is a wise choice, as biographers often get weighed down by his other exploits. He wrote books and the libretto for an opera, designed furniture, jewelry and movie scenery, and barreled through his remaining years in the form of one long performance piece.

The book is divided into sections based on what “periods” followed in Dali’s evolution as a painter. After he abandoned the Paranoid-Critical Method, he became rapt by the atomic age. A huge motif in the work of this period was based on the scientific concept that atoms don’t actually touch. While he was exploring atomic structure, he became fascinated by the Ben-Day printer dots (over a decade before Lichtenstein).

Salvador Dalí, The Skull of Zurbarán, 1956

© 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights

Society. Photo credit: Robert Descharnes / © photo Descharnes &

Descharnes sar

Following that was his mystical/religious period, where he painted some of his largest and most compositionally complex paintings. In this section of the book, we get an in-depth look at Dali’s fascination with da Vinci’s concepts. This book made news recently because of the inclusion of preparatory sketches for some of his geometrically complex compositions. The authors conclude that his last great painting was finished in 1972. He lived another 16 years.

When an artist is this publicity-conscious and aggressively outré, it is easy to conclude that he is making up for a lack of vision and talent. But, by stripping the focus to his painting, it is easy to find much that is admirable.

0 Comments